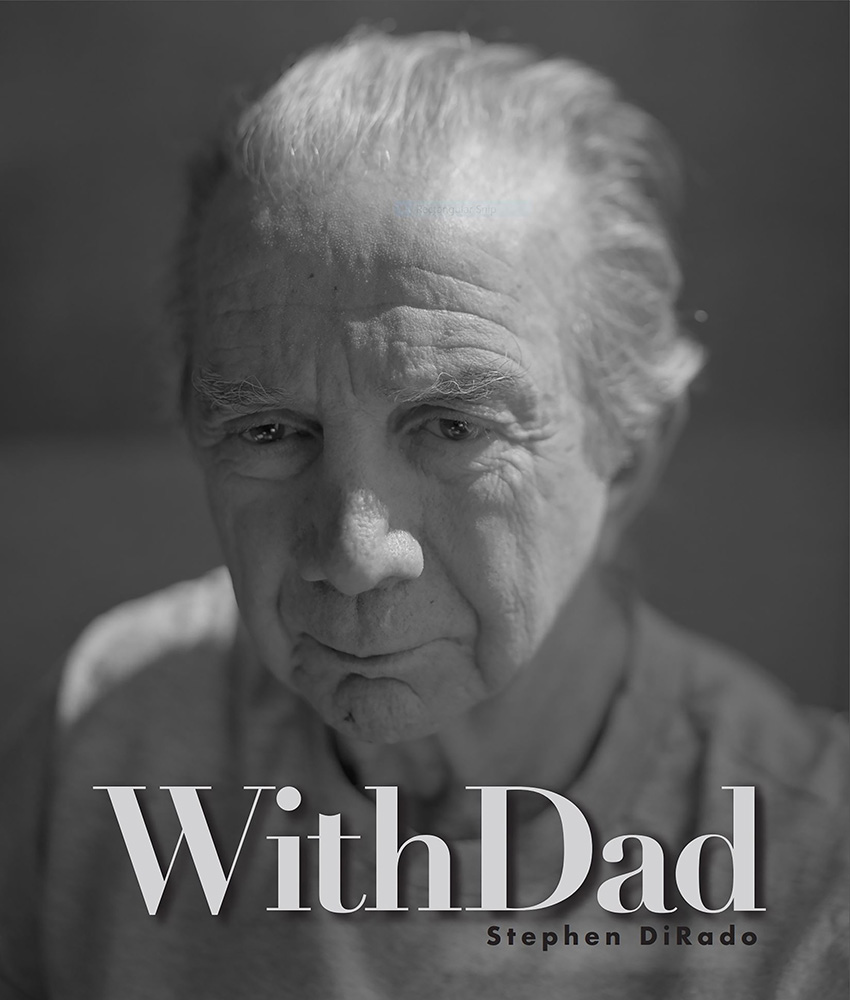

Stephen DiRado: With Dad

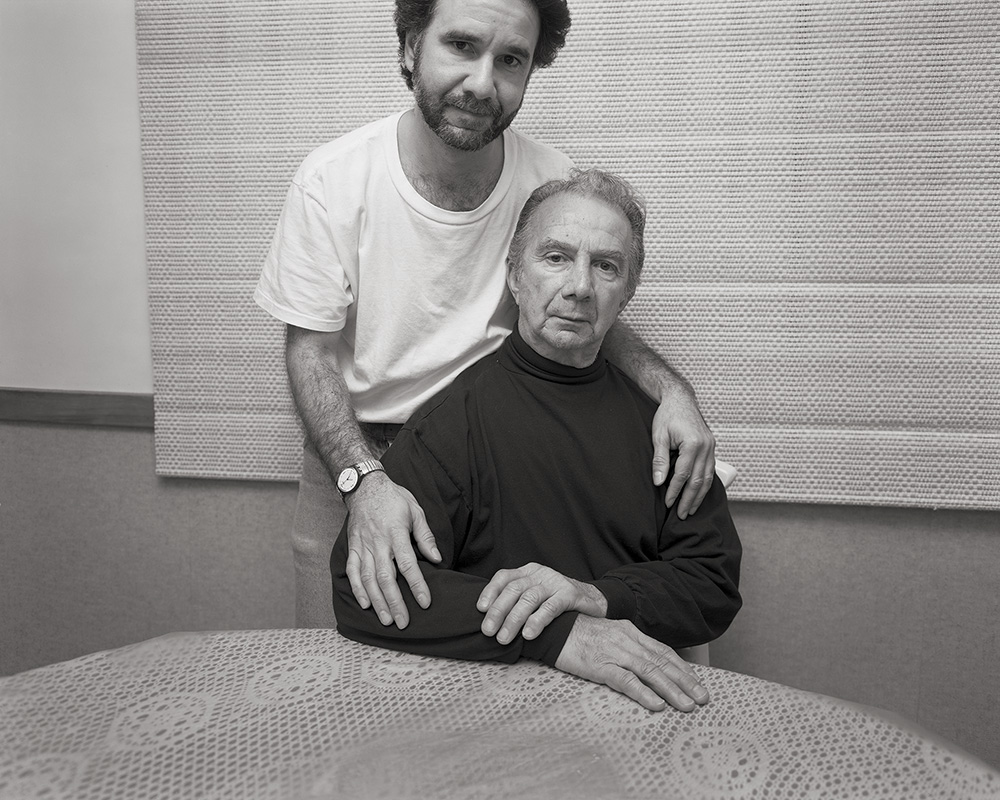

Photographer Stephen DiRado has been chronicling his life through large format photography for many decades and that slowed down nature of looking through the lens has made him consider his world with reverence and deep thinking. One of his long time projects has been documenting his father over the years, and eventually photographing what is tremendously difficult, a parent in their most diminished states. The power of bearing witness to loved ones in crisis, through quiet and meditative seeing, brings a profound beauty and sensitivity to the subject matter.

His touching and compelling new book, With Dad, is an emotionally charged journey that “illustrates the unfolding physical and psychological impact Alzheimer’s had on the entire DiRado family. Stephen’s vision crafted through transformative black and white photographs, empathetically portrays Gene without sentimentality. What graphically is evident is the love, dignity and profound intimacy he and his family endured throughout their ordeal.”

With Dad is a photographic journal that vividly articulates a son’s connections, processed through his camera towards his father Gene succumbing to Alzheimer’s. A chronological span of twenty plus years Stephen, his brother Chris, sister Gina and mother Rose take on a variety of roles caring for Dad in their home, hospital and eventually a nursing home. The result is an emotionally charged book that illustrates the unfolding physical and psychological impact Alzheimer’s had on the entire DiRado family.

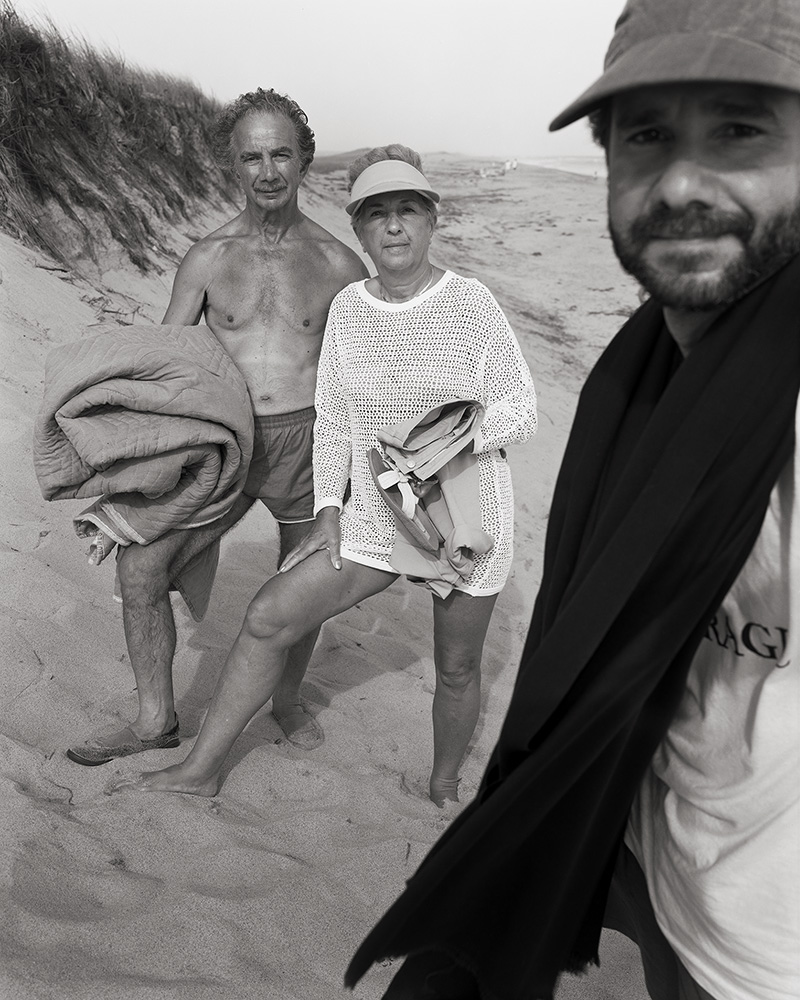

The book concludes nine years after dad’s death with Stephen’s resolve to document his mother Rose’s return home as an active and healthy senior surrounded by family.

Stephan is grateful for the funding by the Bob and Diane Fund which made With Dad possible.

Stephen DiRado is a Massachusetts based educator, photographer and filmmaker whose art is primarily inspired by his captivation and admiration for the people in his community. His scrupulously skilled photographs portray the underlying intimacy of individuals and the interactions within group dynamics. Working within this genre, he has produced numerous portfolios: Past works include his Bell Pond Series, Mall Series, and JUMP. Present work includes, With Dad, Martha’s Vineyard Series, Celestial Series and Across the Table. The internationally prized Bob and Diane Fund awarded DiRado support for the book With Dad published by Davis Publications in 2019.

UNH Art Museum in 2017 exhibited, Stephen DiRado’s Embrace, A retrospect 1983 through 2017, a thirty-year survey of his prolific career. DiRado’s work is in numerous private and public collections internationally, including, Worcester Art Museum, MFA, Boston, MFA, Houston and regional museums throughout New England. He is a six-time recipient of major fellowships that include the John Simon Guggenheim Fellowship, and three Massachusetts Cultural Council Fellowships. His work is published around the world in books and magazines. The Washington Post, Worcester Telegram & Gazette, NPR, Black and White Photography magazine and Vice Magazine, have all featured DiRado’s, With Dad project with feature articles.

Director/producer Soren Sorenson will be debuting a documentary film, With Dad, later in 2020.

Stephen DiRado is a professor in Studio Arts, Clark University, Worcester, MA.

With Dad is available directly through https://www.davisart.com/products/davis-select/davis-select-art-books/with-dad/

Stephen DiRado: www.stephendirado.com

With Dad

Essay from book

All my life I have been photographing family and friends. It is a ritual accepted without prejudice by all, and my way to empathetically connect. In the case of my father, Gene, succumbing to Alzheimer’s, the act of photographing became my way to cope with an intolerable situation. The resulting photographs lay witness for me to unbearably comprehend the deterioration of his mind and body.

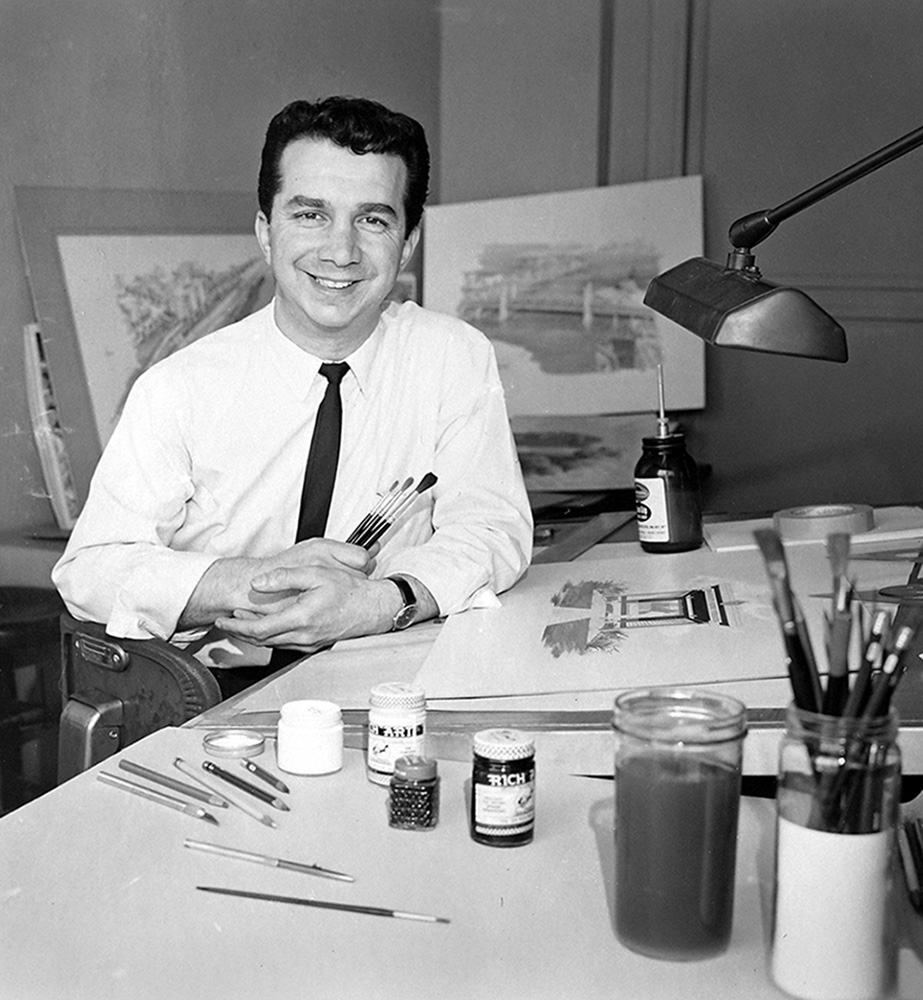

Growing up in the 1960s and early 70s, in a middle class suburb of Boston, there are five people in my family. I am the oldest of three children, followed by my sister, ending with my brother who is five years younger. For decades my father Gene commuted to his job as a praised graphic artist; off to work at 7:30am, home by 5:30pm. My mother, Rose, prepared and served dinner faithfully at six o’clock; a rotation of twenty or so favorite, (and not so favorite) meals. The talk around the table was always based around our day’s events. Evenings, at some point after dinner, Gene went to his studio to work on personal projects and the occasional freelance job. Weekends brought about day trips to touristy destinations and visits to large and small art museums. Uncles, aunts and cousins from both sides of our family figured in on some part of our ventures, including summer vacations at the ocean front beaches or mountains of New England. This was a happy time for me.

Our family naturally evolved with time. All three siblings went off to college and began our own independent lives. After thirty-seven years, Gene retired as a graphic artist for the state of Massachusetts with plans to tend the house he designed and built and to pursue his love of painting. Rose found solace spending more time with friends and family in Florida, residing in a guarded community; going out for early bird specials, playing cards, mahjong, bingo and enjoying local variety shows. Only during the coldest months of the year did Gene fly down to visit. For many years this arrangement worked out well for both, until Gene decided it was too much trouble for him to travel.

Gene, who was now in his 60s, found absolute comfort in his home and manicured yard filled with shrubs and perennials. During Rose’s absence he provided for himself, walking his dog Missy three times a day, content with cooking the same few meals; pasta covered in something, and cold cuts for lunch. He never went out to eat unless I, or my sister, took him out to his favorite restaurant. We frequently checked in on him, followed up with phone calls to each other to make sure he was really ok. My brother joined in on this rotation by moving back home following a decade of living in California. Eventually we all noticed that something was definitely wrong with Gene. Increasingly we found notes by the phone and kitchen table, simple reminders to himself to perform the most mundane tasks. He abandoned his studio, choosing to sit in front of the television all hours of the day, half watching with no real interest in whatever was on. Gene lost any desire to travel, going out to dinner—anything that would take him away from the house. We became alarmed thinking it must be the effects of depression. It wasn’t until he had no explanation as to why it took him hours to drive the twenty minutes to my sister’s house or why he could no longer make change from a twenty dollar bill that we entered into a state of crisis.

In 1998 Gene had his first major stroke. Rose was just back from Florida when it happened. Also, during this time he was diagnosed with Alzheimer’s. Rose immediately took on the role of full-time caregiver, providing for Gene as one would for a toddler. He would eat, wash and go to bed obeying her instructions. Taking him back and forth from Florida ended when Gene could no longer care for himself. Cleaning up in the mornings, he’d shave his beard and eyebrows and eventually his hair. All of his foods had to be chopped up into bite sized pieces, and any attempt to hold a sandwich became an act of despair, sometimes ending with Gene throwing it across the room with an expression of utter defeat. My brother, sister and I began to work rotating shifts to assist Mom. “Daddy Sitting,” we called it. Many weekends we would relieve her of the over-whelming twenty-five hour days required to take care of him. Gene’s world collapsed into a constant state of paranoia. It became an unnerving sight to glimpse him through his cracked bedroom door ghoulishly peeking out. Signs posted by my brother were placed about on doors identifying essential rooms; taped to the bathroom door was a graphic of a toilet. It was not unusual to find Gene standing by its door waiting for somebody to come out, not realizing that he shut the door just moments before.

It was in the fall of 2003 that Gene’s time spent in the bathroom during my weekend shifts increased in frequency and durations of time—as much as an hour. I rarely heard the toilet flush, or water running, just silence. Baffled on numerous occasions I inspected the room after his exit; water off, toilet clean—nothing. Curious, I eventually asked Dad to pose for my camera in the bathroom. Readily he walked into the room and right up to the mirror consciously inspecting his reflection. Quickly framing him within the mirror, I announced that I was about to take the photo. Gene abruptly turned, attentive towards the camera, and smiled. Startled by this, I asked him to turn around and hold his pose. He refused, and in an agitated tone of voice pointed at the mirror and said, “That man is looking at the camera, so why can’t I?” I immediately realized that all his visits into the bathroom were to see this stranger—“THAT MAN!” Devastated, I asked Dad what he thought about this person. He looked back at his reflection, paused, and said, “He is a good man.”

I agreed with him.

Gene and I both looked at the man in the mirror while I made the photograph. I was heartbroken, not realizing or accepting the fact that Gene, my father, was now in the advanced stages of Alzheimer’s. This also became a benchmark for me, asking myself the question: Am I now exploiting a helpless situation and to what real purpose?” I had to struggle to hold onto the belief that my photographs will help others going through similar ordeals.

After Gene’s second stroke and a major cognitive decline, he became too much for all of us, and in July of 2004 he was admitted to a nursing home in the same town he was born in. Rose visited Gene almost daily until the fall of each year when she would leave for Florida, dutifully returning in May. On a rotating basis and with some overlaps, Chris, Gina and I continued to visit—reporting to each other his daily condition. The staff welcomed us to feed and wheel him about in and outside of the nursing home. My camera, was always by my side, it gave me purpose, it gave me permission to physically hold and love him in the only way I knew how.

Each visit to the nursing home, I made it a point to park my car at the far end of the lot. Opening the hatch in the back of the car I’d pull out and over my shoulders a satchel filled with plates of film and then remove and assemble my 8” x 10” box camera onto an oversized tripod. In one sweeping motion, lifting the apparatus over my right shoulder, bounce it slightly back and forth until it fit with perfect balance. Looking up into the sky I’d take time to note the weather conditions, take a deep breath and start walking towards the main entrance. There, I’d take the elevator to the second floor where Gene resided. The ride up gave me time to inspect my reflection within its softly polished metal doors. I often wondered, would I someday look at my own reflection and recognize the stranger looking back at me “as a good man?” As the doors began to slide open, my focus shifted outward, looking into the large room filled with tables, wheelchairs, residents and staff roaming about. In the center of my view would sit Gene—my father. As I took those first steps forward, I would always exhale and say to myself, “Dad, what kind of photos will we make today?”

Gene died on December 11, 2009, eleven years after he was diagnosed with Alzheimer’s.

Over two decades I recorded the horrendous effects Alzheimer’s had on my father. Why did I do it? I did it to hold onto my father as long as possible. I did it to record a disease that, I believe, in time will no longer be terminal. I did it as a visual, visceral record for future generation to see what devotion, heartbreak and suffering looked like for victims of Alzheimer’s and for their families. I did it for my father.

-Stephen DiRado

On April 4, 2018, Rose, at eighty-six, moved back into the home she raised her three children in. Her reason is to live the rest of her reasonably healthy life with family. This is in great contrast to Gene’s final years in the house he designed and built himself. I continue to photograph her by appointments. Not because I am afraid of what I might find but because of what my mother offers: Inspiration.

-Stephen DiRado

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

Andrew Lichtenstein: This Short Life: Photojournalism as Resistance and ConcernDecember 21st, 2025

-

Martin Stranka: All My StrangersDecember 14th, 2025

-

Interview with Maja Daniels: Gertrud, Natural Phenomena, and Alternative TimelinesNovember 16th, 2025

-

MG Vander Elst: SilencesOctober 21st, 2025

-

Photography Educator: Josh BirnbaumOctober 10th, 2025