Lorena Molina: A Studio of One’s Own

In the days and weeks following the initial shutdown of nearly everything because of Covid-19 I saw a great deal of commentary on how things are different, how we as a nation would adjust, and how the smaller community of artists would change their practice. I thought of my own art practice, pictures of and concerned with home life, and realized it wouldn’t change much at all. The five artists I’m sharing with you this week also have home or studio-based practices and worked this way long before a pandemic forced their hand.

We talked about what it is to work this way and why they do it. Is it thrilling to have control over an imagined created world? Is it the ability to escape people? Is it just easiest? These artists work in their basements, attics, school studios, and although they have contact with the outside world, they mediate it, capture it, bring it home to play with it. The pandemic hasn’t affected their art practice as much as it has affected their interior world, making them reflect on their place and what they make. Even working at home the events outside our homes have a profound effect. At the time these interviews took place we talked mostly of the pandemic and school from home. – Rita Lombardi

Lorena Molina is a Salvadoran artist who uses photography in conjunction with video and performance to talk about issues of displacement and home. I met Lorena when we were both living in upstate New York and we became friends. Her work asks difficult questions in a personal, direct and compassionate way.

At the core of her work is an exploration of spatial inequalities and the challenges that oppressed groups face in constructing place and establishing a sense of belonging. Her work is driven by the displacement experienced after a 12 year old civil war in El Salvador forced her family to migrate to the United States. The work deals with the atrocities of war, dislocation, otherness, and white washing caused by the process of making home in the unwelcoming. Her current projects look at identity in liminal spaces. She sees this liminal space both as where extreme violence and pain happens, but also as a place for dreaming of possibilities and potential.

She received her Master of Fine Art degree from the University of Minnesota in 2015 and her Bachelor of Fine Art from California State University, Fullerton, in 2012. Molina was a recipient of the Diversity of Views and Experiences fellowship, The Christopher Cardozo Fellowship and The Kala Art Institute fellowship. She has exhibited and performed both nationally and internationally, such as the Contemporary Art Center, Cincinnati, 621 Gallery, FSU Museum of Fine Arts, The Delaplaine Art Center, The Beijing Film Academy and all over the piazzas of Florence, Italy.

In the classroom, she works with students to understand the way that images are laden with history and vocabulary. Images tells stories, but who gets to tell the story matters.

Through the use of photography, video, performance art, and artist’s books, I explore intimacy, identity, pain, and how we perceive the suffering of others. My work interrogates relationships and the formation of relationships as political acts that are guided by negotiations of power and privilege.

At the core of my work is an exploration of spatial inequalities and the challenges that oppressed groups face in constructing place and establishing a sense of belonging. My work is driven by a deep sense of displacement experienced after a 12 year old civil war forced my family and I to migrate to the United States. Most of my work stems from a need to find and build community. It deals with the atrocities of war, dislocation, otherness, and white washing caused by the process of making home in the unwelcoming.

Ultimately, my work is always asking for witnesses. To witness is to open oneself up to difference. To witness is to acknowledge that, although difficult to understand, unfamiliar experiences and often silenced stories are an essential part of our collective narrative. – Lorena Molina

Rita Lombardi: I saw some of the work you were creating recently which is very studio-based. It feels like your work is very close to home…conceptually as well as literally. Can you talk about that a little bit?

Lorena Molina: I would say that all my work is about home. I think that when you’re displaced by war, or just anybody that’s displaced, finding a place where you belong and where you can be, is very important. I see home as an extremely political place. It’s where you learn to love, and learn to be loved. It’s a place where you can resist, where you can be yourself, and a place where you can heal from a lot of the injustices of the world. But it’s complicated because when you’ve been displaced from home because of war, It is also the place where you learn to fear, and where you learn about pain. So it’s a site that I see as very complex. A site where you want to belong and exist and be loved and just be, but you also understand the history of how you got there and why you have been displaced. I don’t know if that makes sense…

Rita: No, it makes a lot of sense! And you’ll probably deal with that your whole life…

Lorena: Yes, when I was living in Utica I felt so displaced. I felt constantly like an outsider. We lived in rural, central New York and you know, I’m usually the only person of color in art spaces. But there, for the majority of the time, I was the only person of color everywhere I went. So I had this constant feeling of just being an outsider and I didn’t have the network to provide support. So it got me thinking about how it is part of the immigrant experience to feel like something is always missing. And I’ve been thinking about what it means to live and exist in the margins and how I can make a home for myself in that place. That maybe the margins is what I get to have, and that a good enough place. I really see the margins as something really powerful, I see it as a place that has a lot of potential. I see my home in the margins both loaded with pain and trauma, but it’s also a place where I can exist, thrive and I get to keep myself and I don’t have to whitewash myself to belong. In this space, I can keep my accent and I get El Salvador and California and New York and Minneapolis and here [Cincinnati] and all those things that make those place a home.

Rita: That’s such a nice way to rephrase it.

Lorena: Because the other way is really difficult!

Rita: Yes it is! Because you’re constantly an outsider instead of making it your home. ‘This place is mine’ and there is a freedom in that too, you’re claiming it. Nobody gets to tell you what to do in the margins because it’s the margins, ‘so screw you’.

Rita: So, your work is about home. Aside from your performance work and maybe even your video work, correct me if I’m wrong but most of the time you’re working from home or from a home studio, is that right?

Lorena: Yes, that’s right

Rita: So what was the motivation for that? How did that evolve in your practice?

Lorena: I think when I moved to Utica, and I started working on the Nothing Hurts Like Home series, that’s when I started doing that…I was making performance work in the studio before that. To me, the landscape and the space matter so much. It mattered so much to the work that I was making, it was important for me to include it. The cornfields also reminded me of the cornfields that I grew up with in El Salvador. I saw that as a connecting factor to a place that I was aching to go back to, but I couldn’t. In a practical level, I always like to work with what I have. Even before grad school, I never had a studio. I always make work with what I have. I don’t care about fancy equipment either. The camera that you have is the camera that you have. So to me it’s important for my work that I can make work anywhere and that it’s accessible. The sites that I’m using, they matter conceptually, but also sentimentally and I think those two things are important.

Rita: How about your new work? Something That It’s Not Nothing.

Lorena: I started making that right when we went into quarantine. All of my work, for a very long time, it’s about making the viewer or the audience witness to pain and trauma and understanding how they’re benefiting from it or how they’re accomplices. I do that with my performance and video work. I spend a lot of time doing research. A lot of it’s to educate the viewer and understand their positions of power and it’s just so emotionally draining for me. It’s really difficult to make the work. I’ve been thinking a lot about “who am I making work for?”. I think I’m making work to educate and to make people uncomfortable in certain spaces. I think it’s important to politicize the gallery but at what cost to my emotional being? So I’ve been thinking a lot about pleasure and decadence as also political. And that’s something that certain bodies are not allowed to have or they don’t feel entitled to.

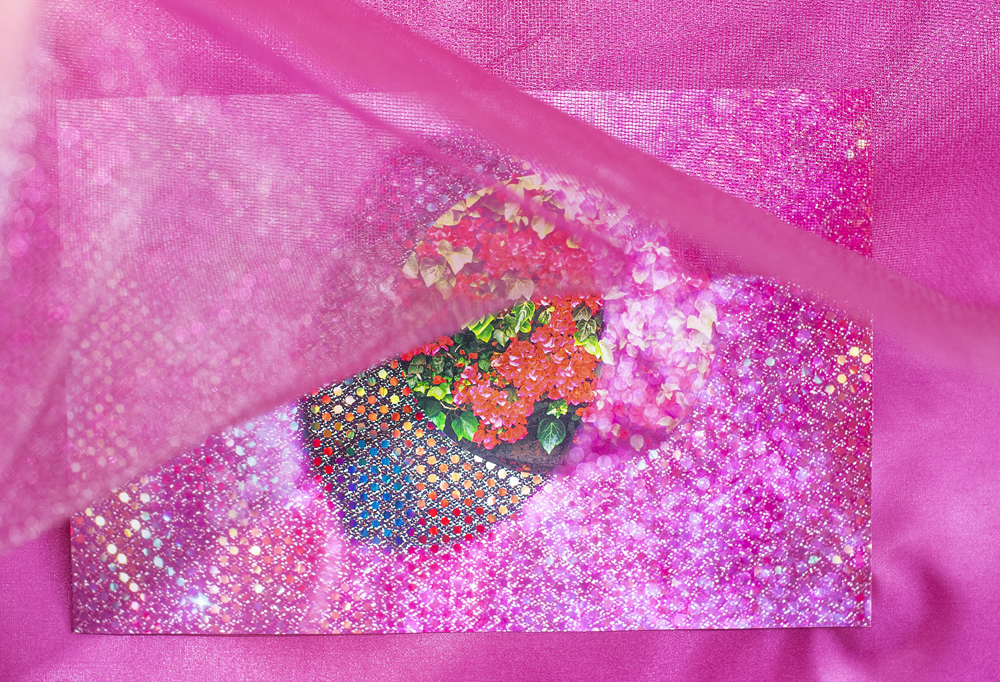

I started making these little still-lives. They’re all still markers of home…the orange photo was shot in El Salvador, the banana trees and the mango trees are such a part of my practice now, The fabric I’m using in all the photographs are from the series How Blue. So I’m just trying to make connections between everything I’ve been making in the past four years. The markers of home, thinking about pleasure and decadence and tying it all together. I’ve been thinking about beauty and brightness and in How Blue I was thinking is there a different way to mourn? Can you mourn with bright colors? Can mourning also be a celebration of life?

Rita: Right, you’re remembering people and they lived!

Lorena: Right, you use items that you remember that they loved or the things that remind me of them. So that’s why the photographs of those flowers and the tortillas and the little guys…acorns?

Rita: Those spiky things? Those are from the gum tree.

Lorena: Oh! They are everywhere in Cincinnati!

Rita: So How Blue and Nothing Hurts Like Home, how similar are they? Are they morphing, one into the other, or are they totally separate?

Lorena: I was thinking about different things. In How Blue I was thinking about the land, I was thinking about mourning, the textile history in El Salvador and how it’s completely lost because of the genocide of indigenous communities. I was thinking about my grandmother and how she was a seamstress and she made dresses for me. How she made clothes for me as a way to show her love. And I was thinking about mourning for this textile practice that was lost and how all in related/unrelated way It’s tied to my displacement. It’s just me experiencing grief for multiple things and also thinking, can I mourn in a different way. So I started using photographs in How Blue and some of them are fragmented. Like the sky would be from another photograph.

I was trying to make new landscapes. To create new sites for longing and remembering. These fabricated landscapes were my ofrendas. My offerings for the people lost in that land, the lost of those skills, and the home that I’m mourning for.

Rita: It seems like you’re finding a way to be at peace in the newer work. Like you said, redefining what home is because you can’t live in the other place, it’s just too hard. These feel sort of optimistic, or at least hopeful. They do feel a little bit like altars. It makes me wonder what is happening beyond the edge of the frame and I like that about them.

Lorena: I think when I started making How Blue and Something That Is Not Nothing I’d been thinking about how identity is layered, so in a way the photograph should be layered and more complex.

I had never made work like that before. I used to take a photograph and that was it. That was the thing! These, I make a setup, I photograph it, I print it, I put it in another set up, so it’s just this layer within a layer that I’m making to complicate the image. I like to think of it as this hot mess that I’m trying to make sense of it but that it’s still valid.

Rita: How would you say your work has changed in the last couple of months, if it has?

Lorena: I think I went into the studio with a lot of patience for myself, a slowness. Sometimes I would just go there with the intention to make something. And sometimes it would work and sometimes it didn’t, and I was ok with that. Something about the pressure of trying to make something “good” just went away. To me it didn’t matter. I’m just thinking “this place is for you, it’s for you to make something that you enjoy and that brings you pleasure and that is very valid”. So I think it just allowed me to be more gentle with myself, more caring to myself and my work. To just slow down more.

There’s so much pain happening right now, so much pain. Sometimes I’m very down on art, sometimes I feel like there’s a real problem happening that art can’t solve. A lot of art isn’t capable of solving the problems. But it can create a refuge, an outlet, just a place for you to work through these feelings. Maybe it’s because I can’t go out, so It’s just me in the studio allowing myself to feel that pain but also make things that are beautiful and enjoyable.

Rita: Who is your work for?

Lorena: Existing in art spaces and academia can be a very painful experience, so a big deal for me had to be to try to figure out who my loyalties is for and who am I making work for. I think it’s for people with similar experiences, like me, people who have been displaced, people who don’t belong one way or another. I want to create places where they can feel joy and enjoy beauty and see and understand that their experience is valid. It is for my students, because I think they are amazing and make me hopeful about the future. It’s for my community, it’s for a community outside of academia and sometimes outside of art. Because of that I’ve been doing a lot of work that is outside of the arts. I’ve been finding ways of volunteering more and doing different things that are outside the arts because that makes me feel like I’m connecting with people and my community.

Rita: Last question. What are you listening to currently? Podcasts, music, etc.

Lorena: That’s hard. I’ve been listening to the Lido Pimienta album Miss Columbia. It’s all in Spanish, it’s hopeful and alive and it’s talking a lot about ideas I care about. And because I’ve been thinking about the very sentimental, tactile and intimate side of photography, I’ve been reading “Feeling Photography” which is a collection of essays by Elspeth H. Brown and Thy Phu. It’s a really great book. I think those sentimental conversations are sometimes removed from the contemporary photography dialogue and it’s a great to see a book all about feelings and photography.

Tu Nombre Entre Nuestras Lenguas

El Mozote is a small town in El Salvador, and the site of the deadliest massacre in recorded Latin American history. On November 11th, 1981, 988 people, mostly children, were murdered. This atrocity was carried out by the Salvadoran army, trained in North Carolina and funded by the US government. For nearly 30 years, the Salvadoran government denied that this massacre had happened; the victims’ bodies and names lost between the terrain’s red clay and mango trees.

When trauma occurs, the act of telling stories becomes an important tool of both remembrance and resistance. Tu nombre entre nuestras Lenguas, was a ceremony for those who were lost at El Mozote. By bearing witness to a history unknown to most, participants contributed to a shared ritual that acknowledges the long history of the United States’ implication in the affairs of other nations, displacing families and directly contributing to the refugee crisis.

Tu nombre entre nuestras lenguas was a performance, video, installation made at the

Contemporary Arts Center in Cincinnati. It was a one to one intimate ritual. Participants firstwatched and listened to Rufina’s Amaya testimony. Later, they entered a room full of mangoesand buckets of red clay where they were asked to read the name of one of the victims out loud. After reading the name, they were offered to take a bite of a mango that I sliced in front of them. While the sweetness of the mango was still in their mouth, they were asked to repeat the name of the person murdered. Finally, I marked them with the red clay, and I told them that this was their history as well and to take the name with them.

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

Photography & Anthropology: Gloria Oyarzabal, “USUS FRUCTUS ABUSUS”May 3rd, 2024

-

Earth Week: Aaron Huey: Wallpaper for the End of the WorldApril 26th, 2024

-

Earth Week: Casey Lance Brown: KudzillaApril 25th, 2024

-

Tara Sellios: Ask Now the BeastsApril 6th, 2024

-

ALEXIS MARTINO: The Collapsing Panorama April 4th, 2024