Norma Córdova: Let It Go

Projects featured this week were selected from our most recent call-for-submissions. I was able to interview each of these individuals to gain further insight into the bodies of work they shared. Today, we are looking at the series Let It Go by Norma Córdova.

Norma Córdova, aka, shesaidred, is a Mexican-American photographer, filmmaker, and artist, known for her framed dream-like cinematic stills. She is based in Oakland, California where she still works traditionally, shooting film, polaroids, paper negatives, and making darkroom chromogenic prints, and occasionally incorporating mixed media. She was born and raised in Oregon, by hard working Mexican immigrant parents and initially trained and practiced as a hairstylist before becoming fascinated with the world of photography and filmmaking. When not in the darkroom or filming, you’ll find her interpreting for the Lawyer’s Committee for Civil Rights.

Let It Go

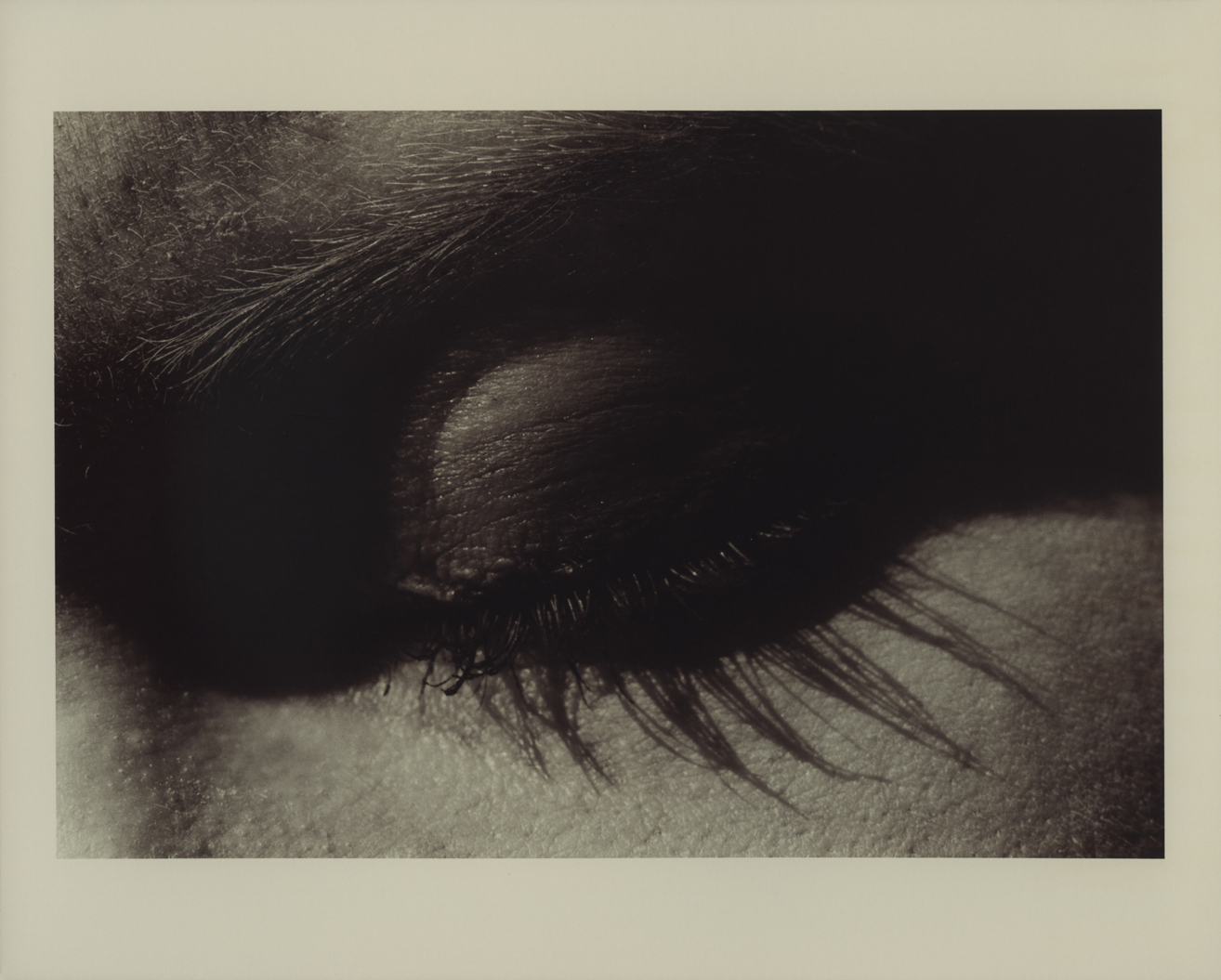

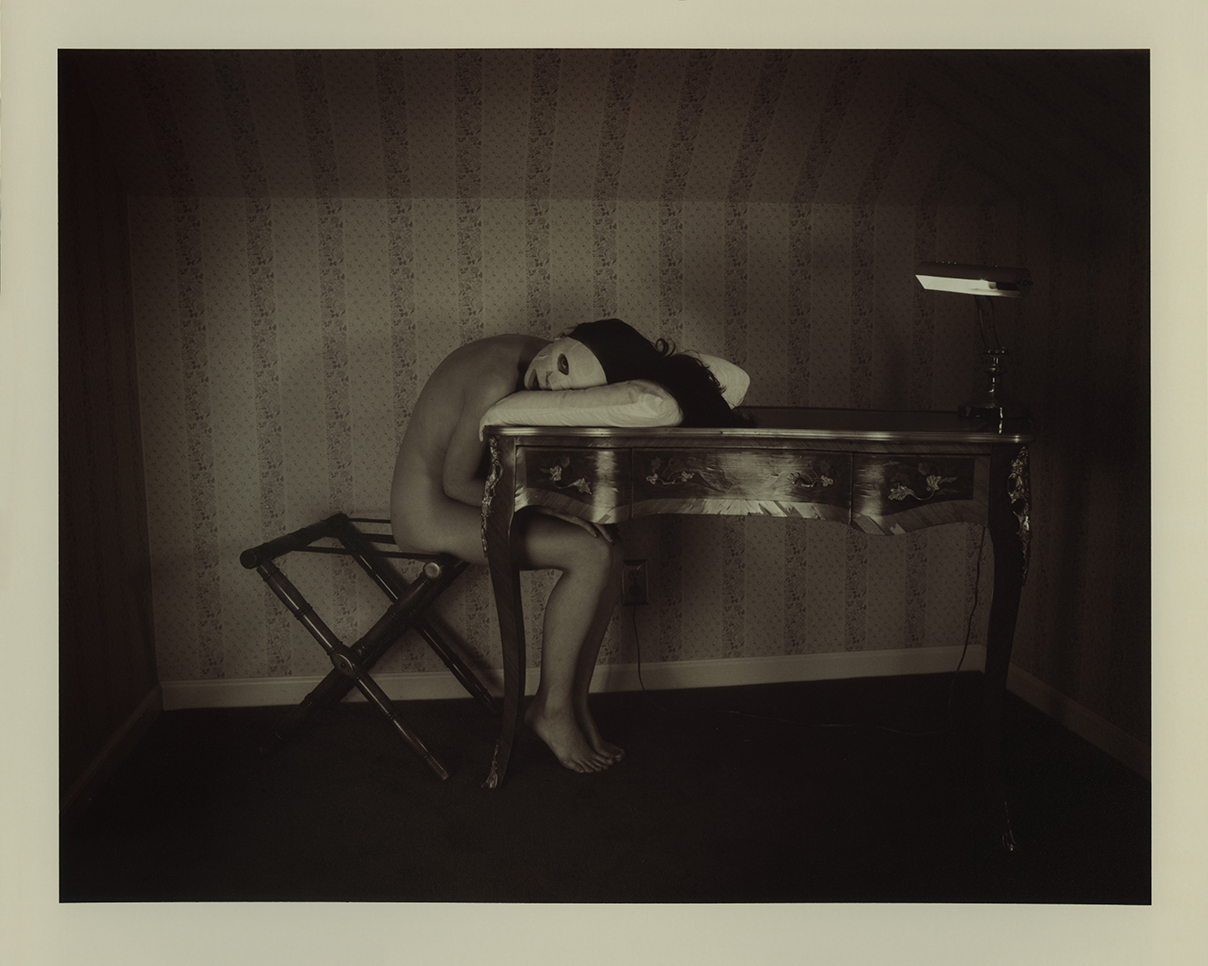

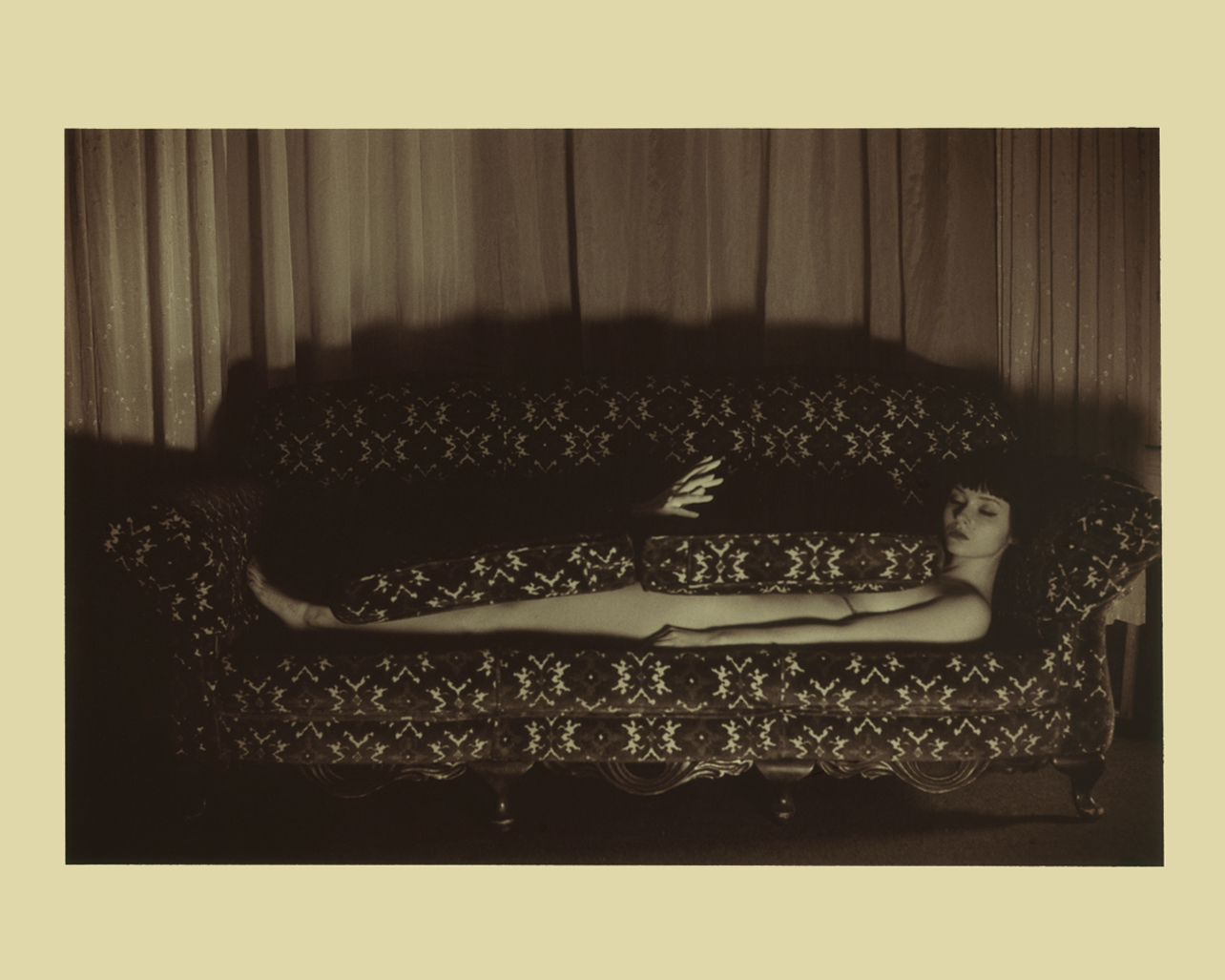

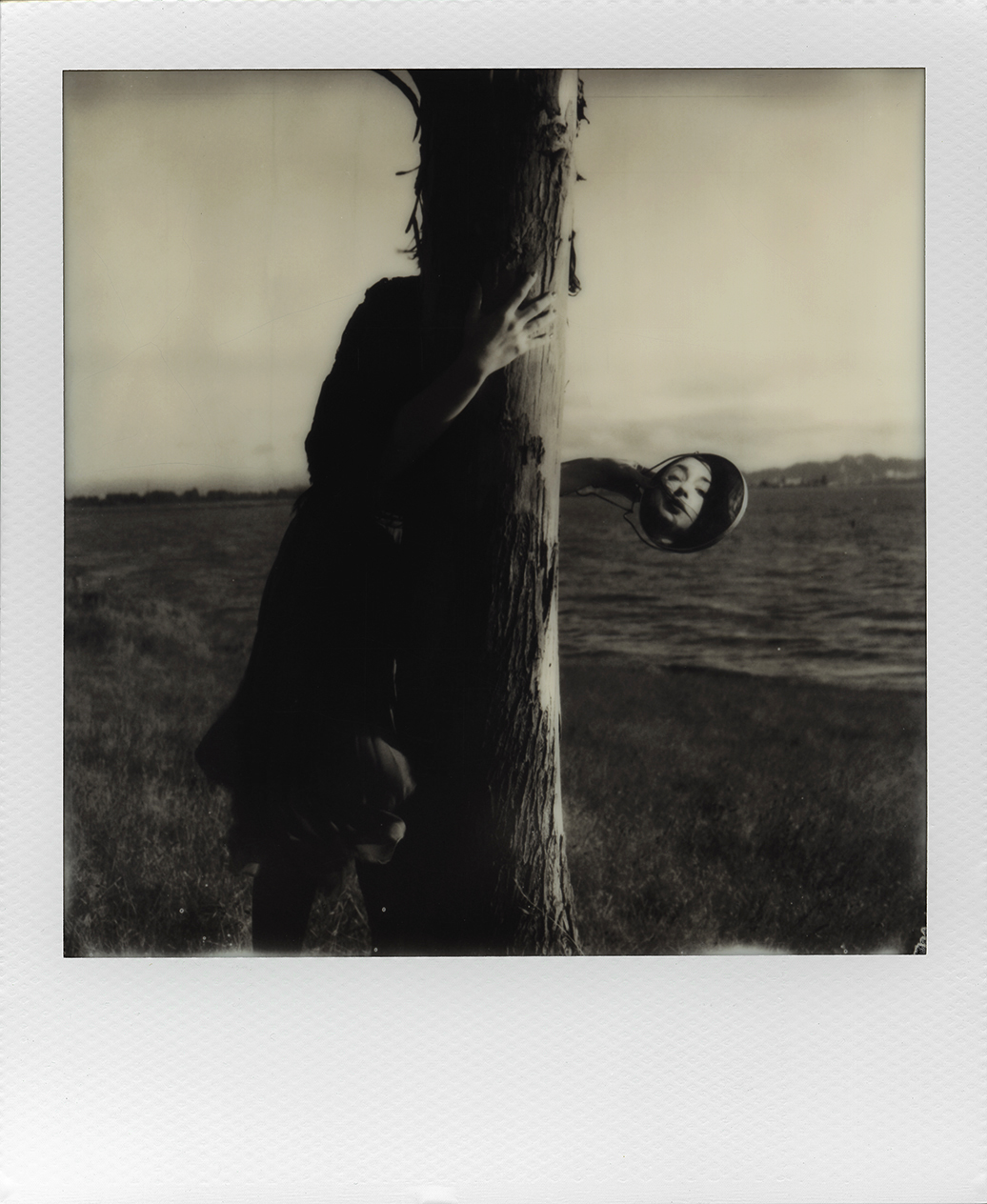

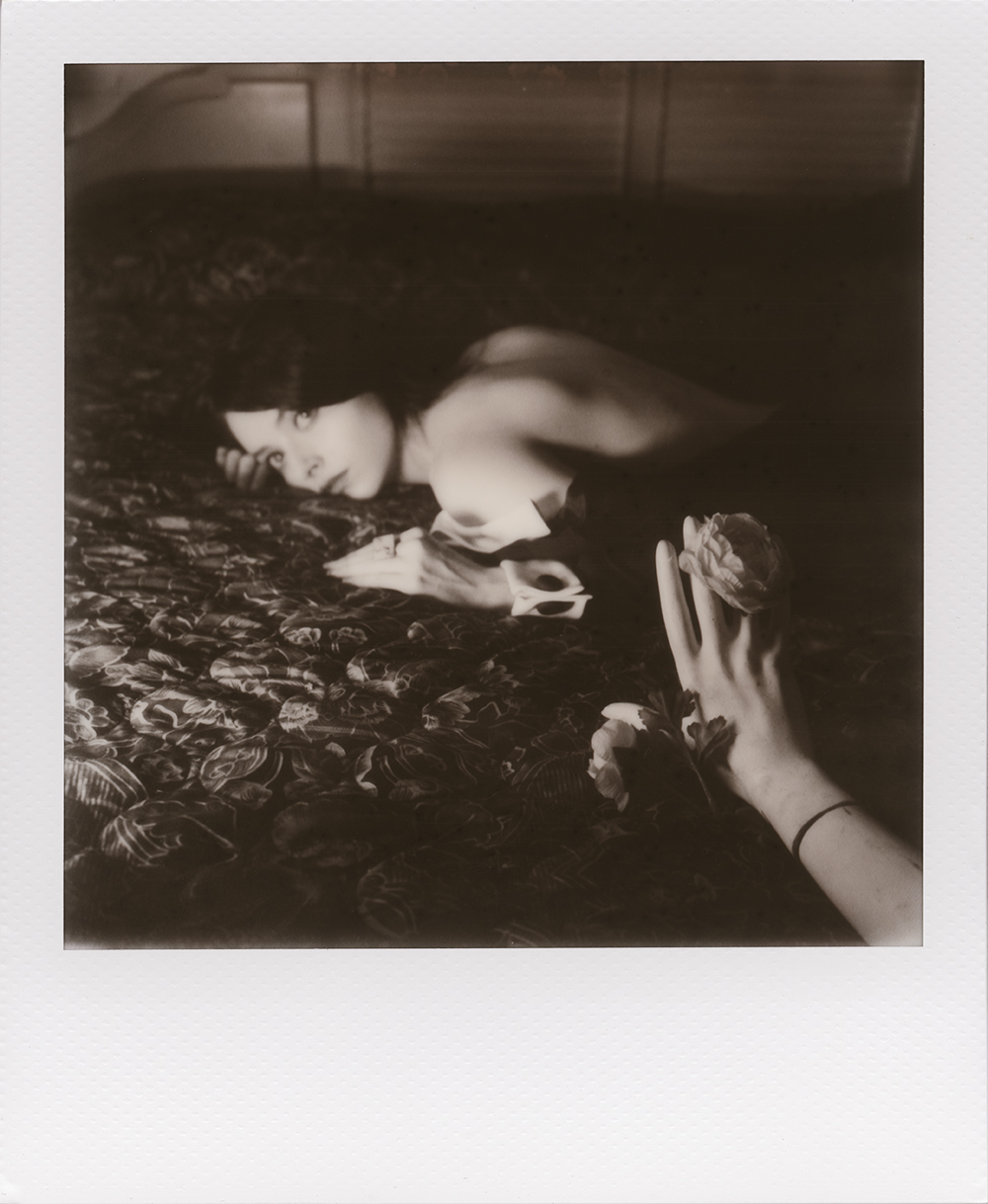

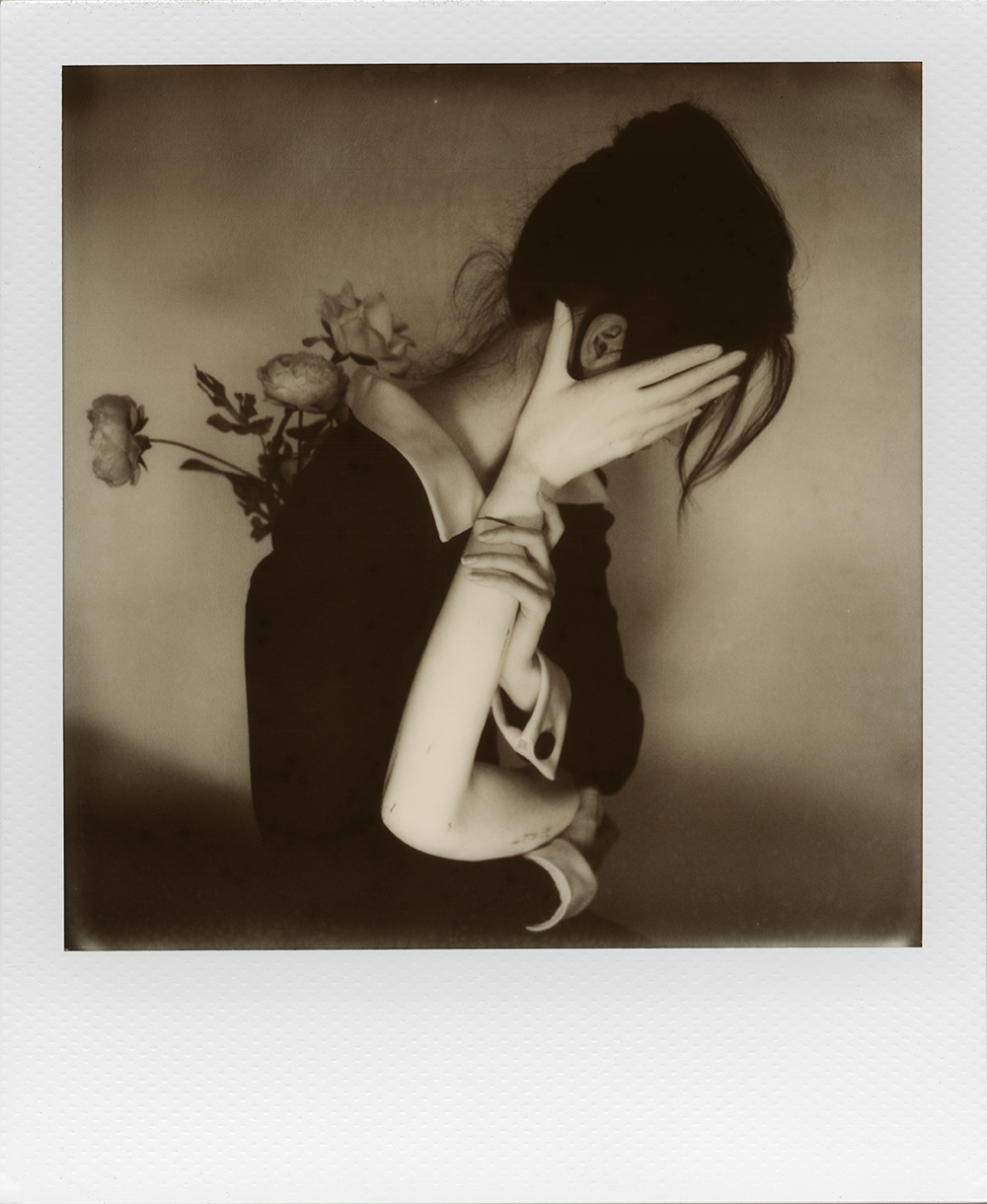

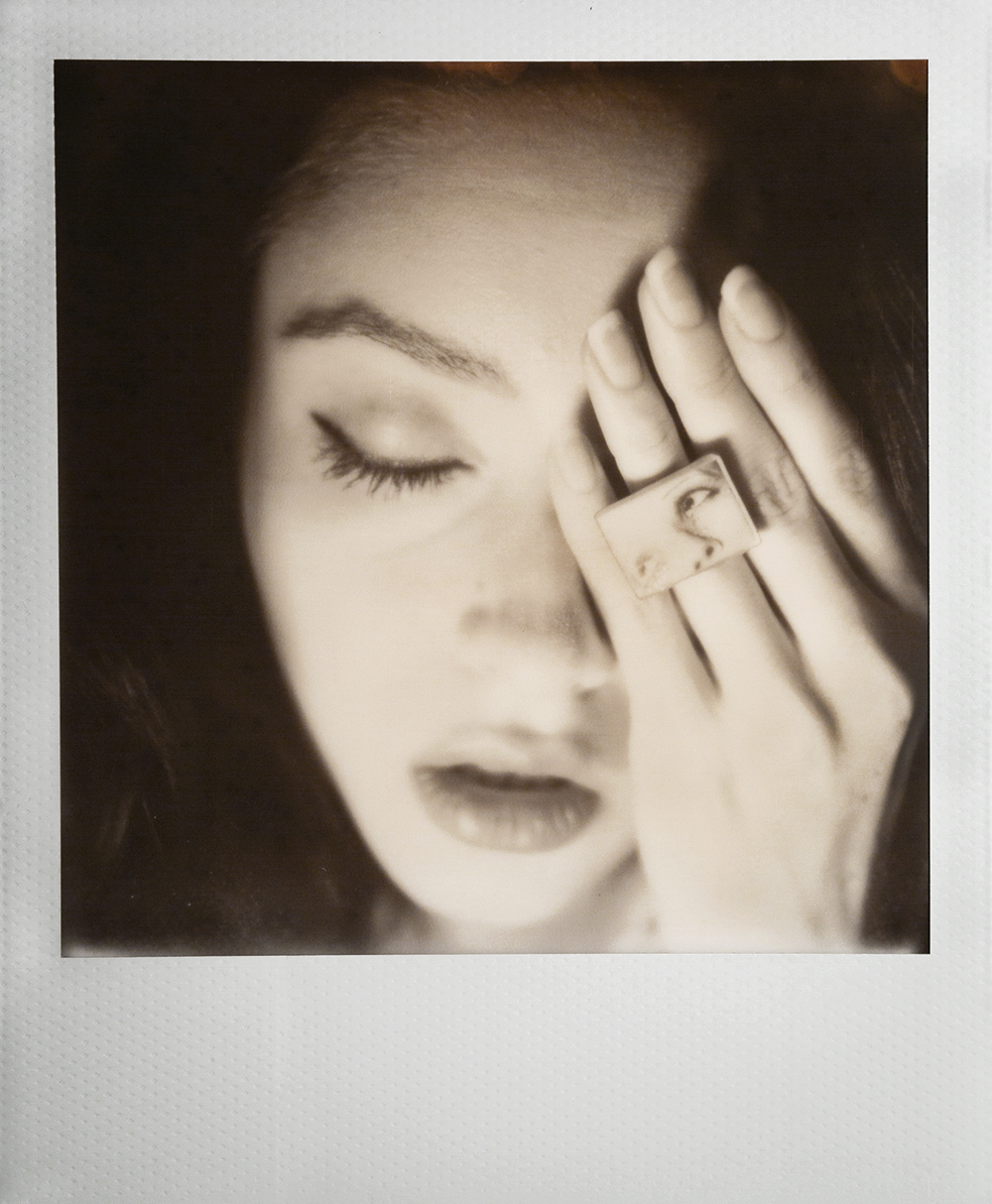

Growing up as a Catholic Latina, I was very aware of well defined female roles. At the time, I did not dare to question them out loud. I adhered to them innocently, thinking that this was the way the world operated. In current times, some photographs of females are often stigmatized as one dimensional representations of women to appease the male gaze. But what if one, as a female, chooses and sees herself as a desirable being? Does that mean one’s images should be subject to the old male gaze contextualization? Can women ever fully be free to embrace that side of themselves without inviting judgement? What if the feminine choses that side of themselves? Or better yet, what if the self sees themselves as a desirable being? Does choice not matter? Is that not what freedom means, challenging, or letting go of preconceived notions? I find myself photographing women to liberate myself from my ghosts’ past. I explore femininity collaboratively, photographing close friends and acquaintances. We come together. There is a relationship built on trust. At times, it comes from unspoken words, a synergy between the two. There is a femininity-full, frank, and free. Throughout my work, I use moody narratives that evoke life’s dark nuances of fear, anxiety, and pleasure, freed from worries about “gendered gaze”, just a photographer, trust, and time well spent among friends.

Daniel George: You mention that growing up you were aware of defined female roles in your culture, but hesitated to “question them out loud.” What eventually prompted you to “liberate [yourself] from [your] ghosts’ past,” and why through photography?

Norma Córdova: Within the walls of my Mexican family upbringing, there were very well defined female roles. It meant getting married under the eyes of God, having children, and tending to a husband’s needs. I did none of those and that became my initial protest against that belief system before I ever picked up a camera. From an early age, there was a lot of shame instilled about my body. I received direct and indirect messages. My body could easily be seen as provocative, depending how clothes clung to my natural Latin curves. I could not help that unless I wore loose fitting clothing and standing a mere 5ft tall, those clothes could easily engulf and vanish those curves. But I enjoyed fashion and definitely would notice how certain clothes could provoke attention like “too much skin” poking out from beneath the cloth. Being nude was forbidden, private, not even in the presence of other women was it permitted in my household. There was a lot of conflicting messages sent my way. In the Latin media, scantily dressed women danced on family programs like Sabado Gigante while at the same time, my mother couldn’t even undress in front of me. She would simply turn her back towards me that’s when I knew I needed to leave the room. In school, the girl’s locker room made my stomach churn with anxiety, and looking at myself nude in the mirror felt dirty. It was uncomfortable. I admired women who wore their figures fully – without real concern, clothed or nude. They oozed this liberal non-judgmental way of just being comfortable in their skin. I desired that and still do.

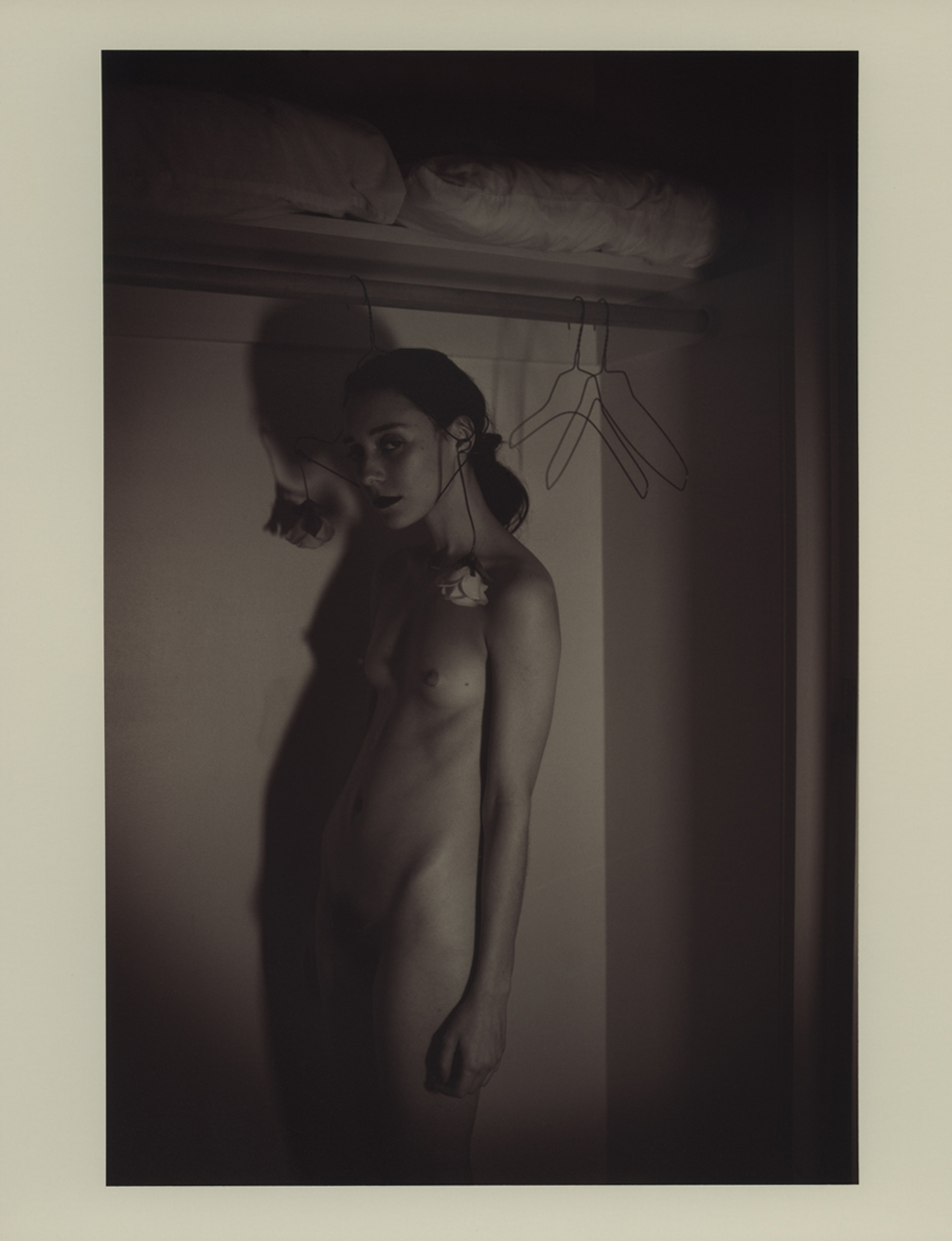

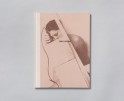

I enjoy photographing women. They are the sisters I never had. They are uninhibited – comfortable in their skin without holding harsh preconceived judgments about their bodies. They trust me and feel safe in front of my lens. They share their inner life shadows that sometimes can remain closeted for life. I soon realized that some of those conversations started to naturally reveal themselves in my photographs. My dear friend Alexzandria in a shadowy closet with a coat hanger under her chin has many deep layers: abortion rights, a wallflower, and the feeling of being closeted to name just a few. These are some personal convictions that I have had to challenge within my own upbringing. I have had others say that my photographs have made them feel something about their own personal convictions. My photographs hold ambiguity within their frames, allowing others to step inside.

My inner voice comes out in my photographs. So I ask, should so much judgment continued to be placed on women, especially their bodies? I find it rather ironic, society wants to liberate women, yet society still tells women how they should be viewed. Not to appease a “male gaze” not to be like this or the other. As a woman, I ask what can women really do and be free of judgment? That’s a lot of weight put on women’s shoulders and that’s where the dismantling needs to start. By asking subjects how they would like to be portrayed in the photograph themselves. Is it ok if we both collaborate on this photograph or is ok that I am photographing you at all? My uncomfortable past beliefs sometimes surface in my photographs, wanting to be released just as much as a friend sharing personal struggles. The tip toeing in a mirror from the point of the view of my friend’s toes amplifies a distortion of what one holds to be the truth. But what is that distortion? Is what you see in the mirror the distortion or is it the distortion of the truth? I know that for my friend, “they” have had to tip toe about not wanting to be boxed into any specific gender with their family. And for some, this image may just look like surreal toes in a mirror. My mind thinks along both lines. I invite viewers to look closely at my photographs with their own convictions.

DG: You also write that this exploration is a collaborative effort. How would you say this manifest in your process and photographs?

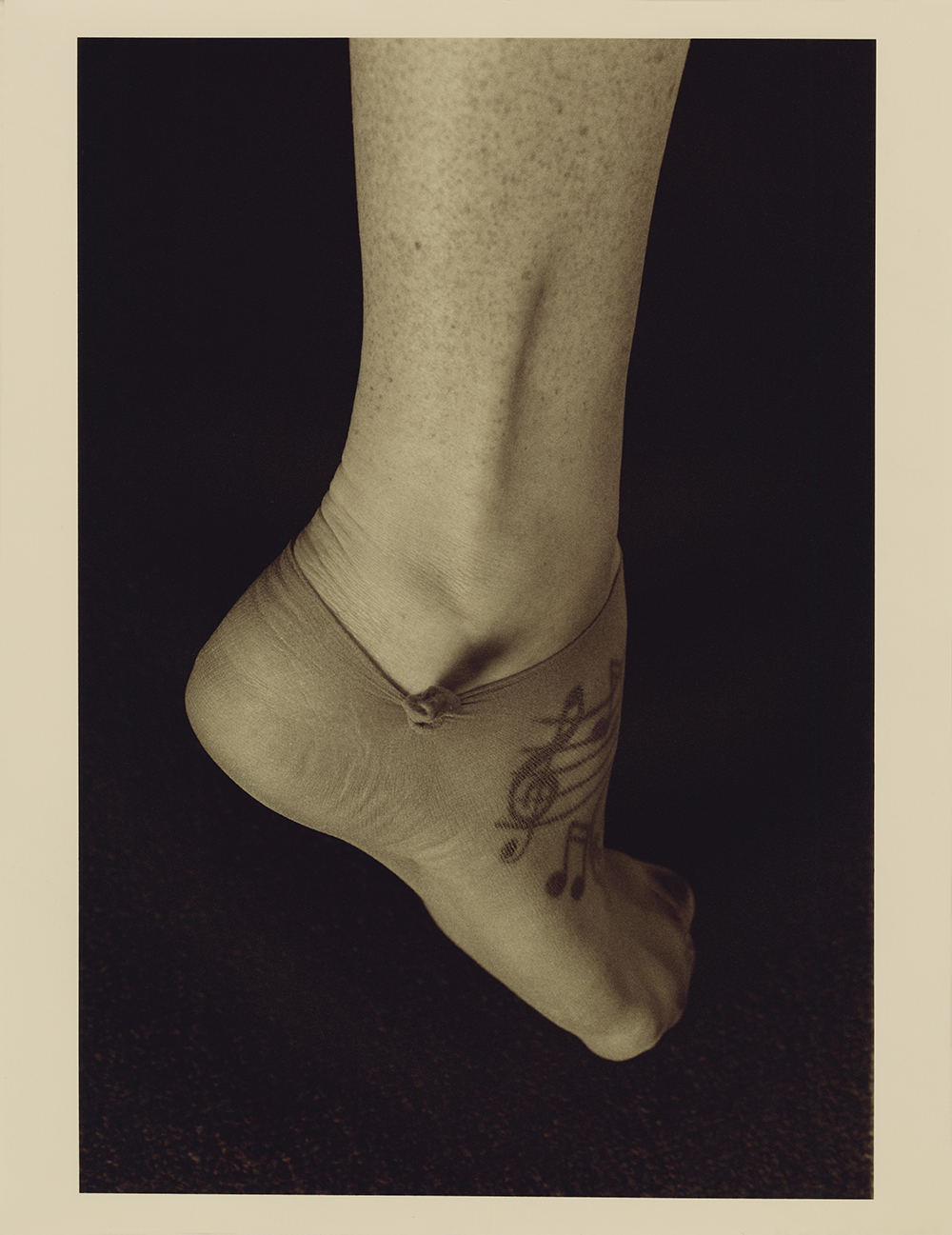

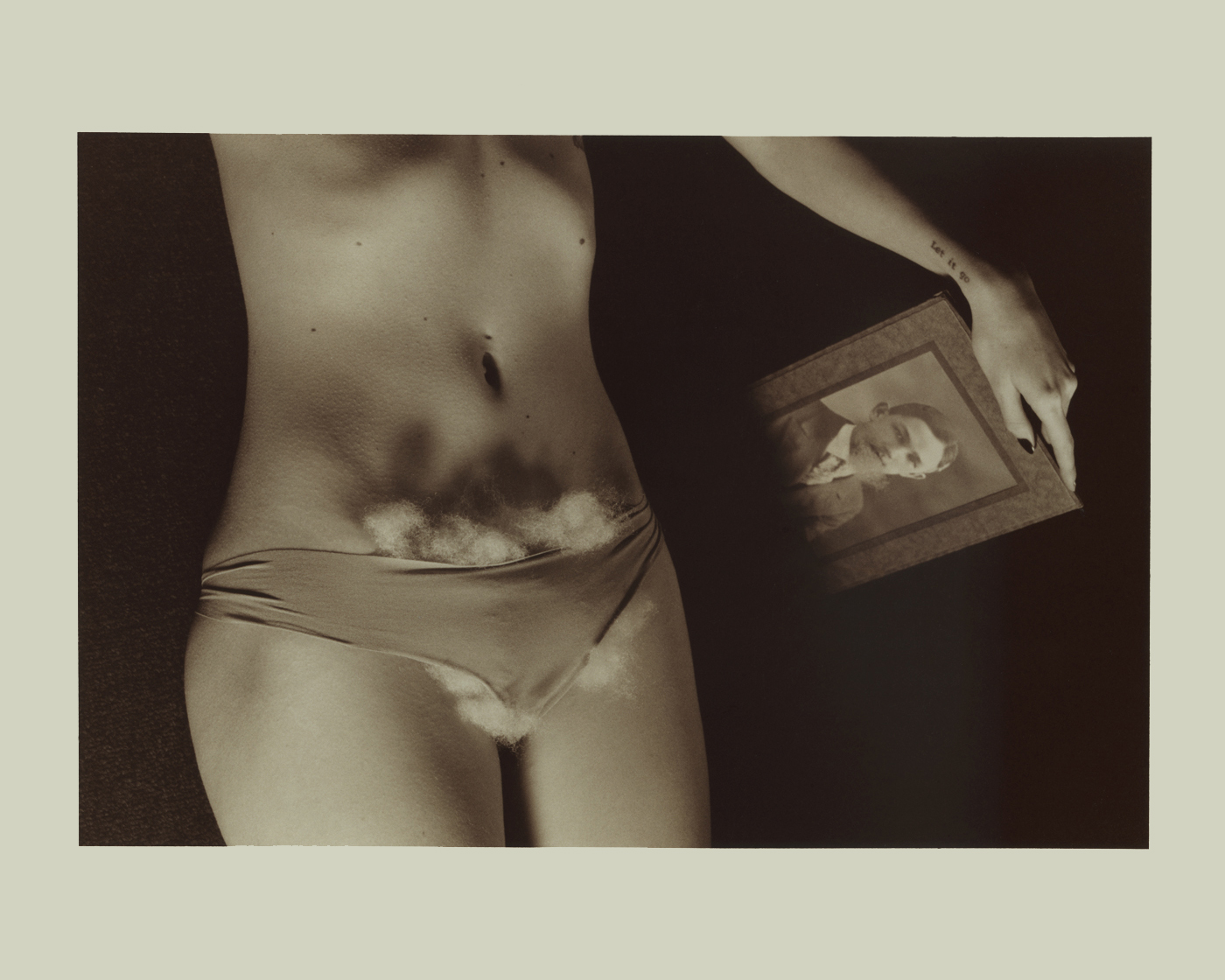

NC: Yes, collaborating with my subjects is more than a simple meet up and shoot. And the times when it was a simple meet up and shoot, the results lacked what I was looking for – an inner emotional presence and connection. My subjects are either my friends, or if not, we definitely become friends after sharing part of ourselves with each other. We spend time getting to know each other over lunch, or dinner, sharing personal stories. Car rides are perfect moments to have casual chats that lead to deeper conversations. We share and listen. I feel like my shoots are between the sisters I never had growing up. There’s this trust that emerges when one divulges personal life hardships and that changes the atmosphere between the photographer and the subject. There is something more meaningful that gets transmitted than a few clicks of the camera. We discuss what I was thinking and I invite them to participate with ideas, and sometimes things just happen at a whim. One particular example of this that pops into my mind is the image of the cotton stuffed in the women’s underwear while there’s a male photograph looking on with a cotton beard. That just happened because of the tattoo on my subject’s arm which stated “let it go.” It represents something deeply personal to her life story. And that statement just resonated deeply with those pressures I felt as a Latina growing up about my body insecurities and the pressures of needing to keep certain topics under wraps, like not being able to discuss menstruation openly, or sex, which was definitely framed as a tool for procreation and for male pleasure. My mother was a woman of her generation and upbringing. She did not really question those ideas. When I photograph, I want it to be collaborative, it’s much more creative and intimate. Sometimes, I get fixated on something and then my girlfriends say what if we do this and I just let it happen. It’s a two way street. I first ask if it’s ok to photograph wearing certain articles of clothing or if being nude under couch pillows with mannequin hands coming out of shadow is ok. The viewers can unravel the layers later, if they so choose to.

DG: After reading your artist statement and studying your images, I of course thought about the male gaze and its influence on the representations of women throughout the history of photography— with visual nods to pictorialism and surrealism. I am going to borrow one of your questions, so in what ways are you letting go or challenging preconceived notions associated with the medium?

NC: I come back to my question, can women ever truly be free to embrace their bodies as they choose, without inviting judgment? And as a viewer, can one truly escape the preconceived male perspectives in modern culture? I believe the answer is complex. This practice of judging women’s bodies has been embedded in culture for hundreds of years, and supercharged recently by a market driven economy dominated by a Western “male gaze.” It has been monetized. So it’s a deeper question that needs to continue to be looked at under a magnifying glass. My photographs are not selling a glamorized idealized lifestyle, or attempting to appease a male audience. That is not what I set out to do or even entertain. My work is not just about embracing one’s feminine skin, which is only skin deep, but more about the sharing of intimate conversations. These photographs are personal female experiences. Some of my images may convey the pressures of being a female in a male dominated society – a feeling that is shared with many other women, not just Latinas.

So the easiest answer to your question is that being a female author of my photographs already challenges the status quo, as history shows that the art world and photo markets are still dominated by Western Euro men.

The majority of my photographs have personal stories linked to each of them. I am taking the time to have those intimate conversations. In one of my recent polaroids – Vera holds flowers in the light, wearing the very gloves I have used to give chemotherapy medication to my cat, Jalisco. I do not know if I am furthering the medium and I certainly make no claims that I am reinventing it, but what I do know is that I am voicing the female inquietudes that other women may or may not relate to. And at the same time, I am paying homage to a historical practice by continuing the use analog tools and processes. In my creative process, my photographs hold a deeper gaze than the one just at its surface. They are not meant to be scrolled at instagram speed.

DG: In your photographs, you juxtapose props and utilize subject positioning to generate narrative. Tell me more about the significance of these performances.

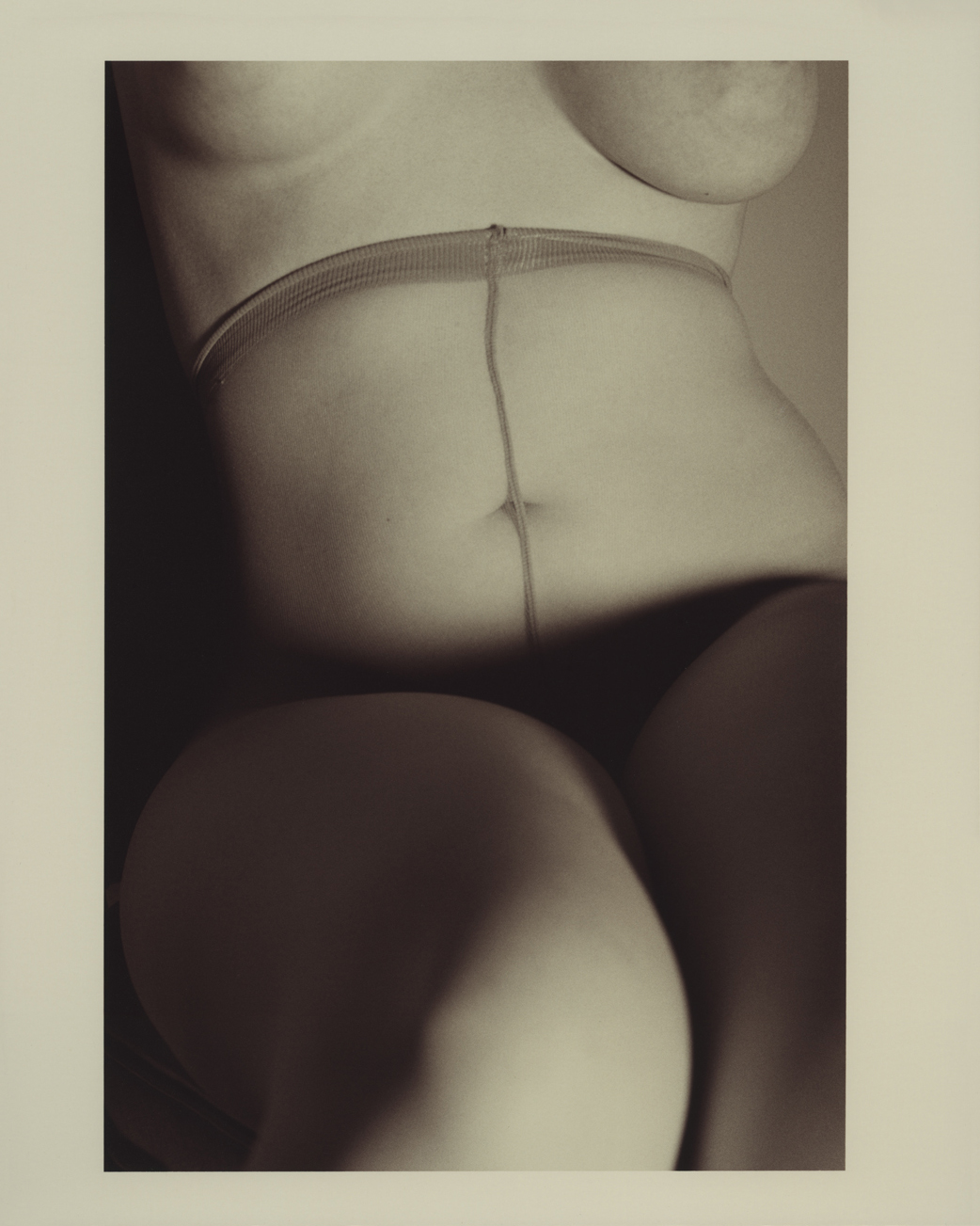

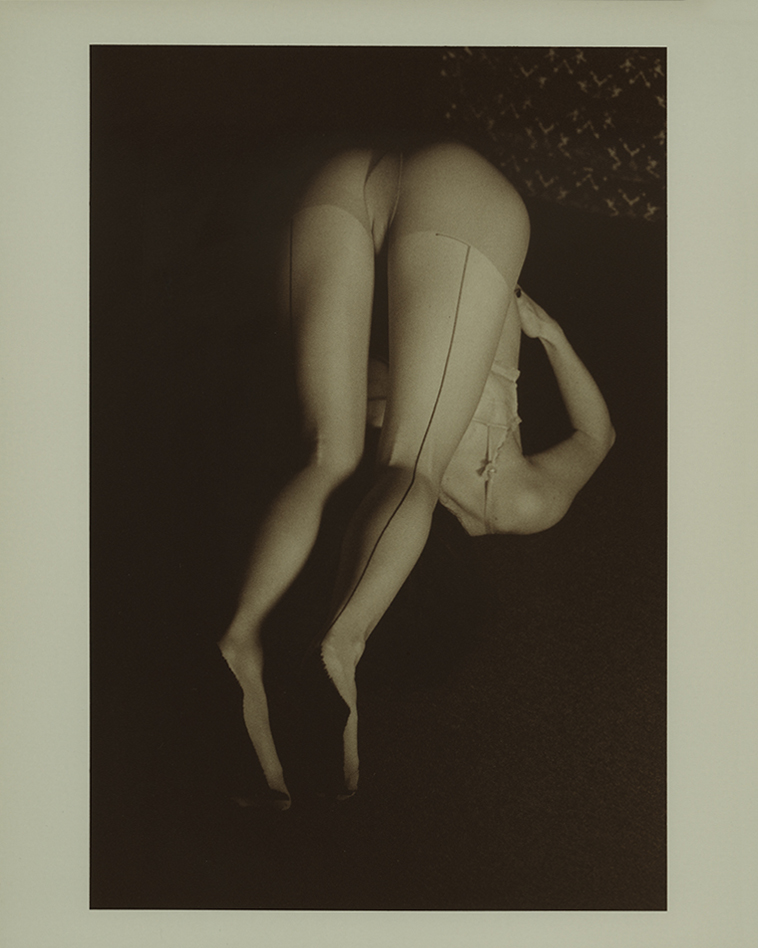

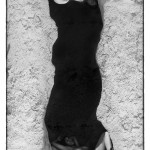

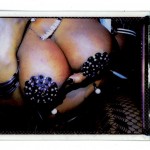

NC: Certainly, props in my photographs emphasize emotions: loneliness, isolation, inner shadows, and self reflection. The polaroid of the woman covering her face with a mannequin arm conceals her identity while flowers blossom from her spine speaks of femininity being concealed. It’s my ghost’s past reemerging: of not being able to speak freely within my own household, of not having that female confidant – the companionship where I could freely ask, why is my body’s landscape changing so rapidly when all the other girls bodies are not developing at the same rate as the Latina’s bodies? I was teased by the boys while my body blossomed. And I think most girls were. In my personal experience, I couldn’t just go home and say “hey mom, the boys were snapping my bra when we played tag outside!” I was too young to have the vocabulary and truly understand my female narrative. My narrative was too busy being wrapped up being embarrassed and feeling shame. The photograph that seems like a simple nude image uses panty hose pulled up beyond the waist. This image holds vivid and visceral memories of being annoyed of having to pull my own panty hose past my waist. They were too long for my stature and sat right underneath my bosom. It was frustrating wearing them to church and having to hike them up so high. Again, I didn’t set out to shoot the polaroid, but I did set out to shoot the nude in this particular way. I endured the discomforts of panty hose just to conform to the social expectation that “proper ladies” don’t expose bare skin at church. And now presented in this light, that can easily be misconstrued. So again who is judging? Am I, as the photographer, freely able express those feelings of my choosing? Or must I self-censor lest my photos be mis-construed? These panty hose still sit this high on my body when I do chose to wear them, which is hardly ever unless I need a layer of warmth or for a bright color splash in my wardrobe, but this time, I am not concerned about hiding my flesh.

DG: You are both a photographer and a film-maker, and from looking at (and reading about) your other projects, you seem empowered by these mediums to explore and consider subject matter and themes that are otherwise inaccessible. How do you feel these ways of seeing and recording enable you to further scrutinize particular content?

NC: Yes, being a female photographer has certainly helped uncover some my personal convictions, but I think it has also made others possibly hesitate a little and wonder. For myself and my subjects, the most important part is the willingness to share openly about our female experiences before the first click of the camera. These conversations hold much weight in my process. From those conversations, my process sheds light on an image that may cause an unease for a viewer. Which is the basic idea, the freedom of my visual voice to express myself. Ultimately, I realize I will have no control over whether the viewer over or under interprets my images. But I do believe that being a woman and coming together to collaborate with other women brings some open vulnerability about being a woman in modern times. These conversations about women’s bodies with women, and women expressing their own trials and tribulations helps bring up other conversations. As women, our rights about our bodies are still being questioned. Are rights truly given to women to explore and to express themselves freely? I mean it’s 2020 and our abortion rights have been put on the chopping block. And the image of my friend standing in a shadowy closet with a coat hanger under her chin speaks to that uncomfortableness that women still face. Even in our current times, women are still not liberated from judgment. We are still raked through the coals for choosing to be nude, and certain subjects are still met with discomfort. Averted eyes take hold in everyday conversations – menstruation, and menopause. These should not be difficult conversations, but still seem to be in our everyday lives. For me, the women in my culture came from mothers who were taught not to discuss these “female” issues publicly. It is certainly a point of conflict to say the least. Especially in a world of Snap Chat, Tik Tok, and Insta culture. And yet old taboos built around a natural bodily monthly occurrence still linger in the air, and the right to choose an abortion is still being threatened. It can be very polarizing and conflicting because the desire to feel free and sexual can simply be turned on its head.

At the moment, my mind has been on the Black Lives Matter movement. I am selling prints to help raise funds for organizations helping “People Of Color.” I set up this site: shesaidred.bigcartel.com with links to the organizations where the proceeds will be donated. One receives one of my prints and in exchange I donate to one of those organizations. On July 11th, a couple of my images will be part of the Colorado Photographic Arts Center Annual Members’ Show

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

Christa Blackwood: My History of MenJuly 6th, 2025

-

Jeanette Spicer: To the Ends of the EarthJanuary 21st, 2025

-

Smith Galtney in Conversation with Douglas BreaultDecember 3rd, 2024

-

Tarrah Krajnak: Master Rituals II: Weston’s NudesMay 30th, 2024

-

European Week: Sayuri IchidaMarch 8th, 2024