Mitchell Squire in Conversation with Douglas Breault

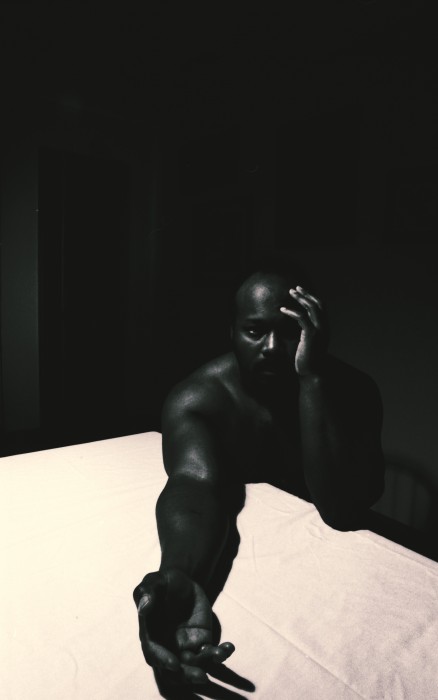

Mitchell Squire does not shy away from looking you dead in the eye. The artist is the subject in most of his photographs, offering a direct proposition to the viewer that feels as if you’re being let in on a secret. Squire is often uncontained and uncensored in his self-portraiture, activating the frame by layering symbols and actions through improvisational moves with the camera. His creative practice is steeped in understanding how the body interacts with objects and space, both as an architect and artist. Squire’s work is a translation of humanity and his energy is palpable in the images, which often come off the wall to physically occupy space within a gallery. While his expertise in architecture and photography are separate practices, it is inevitable each medium has characteristics that intersect and inform the other. Squire himself takes on the potential of a monolithic structure, steadfast in his ability to activate space for the camera.

I first came across his work when published in Ain’t Bad, and the portfolio was a collection of self-portraits where Mitchell is a stoic force braving the elements of snow and sun. His form is prominent within the landscape, often adorned in glitter, paper sculptures, or natural relics to activate the protected space of the wilderness. His investigation within nature feels intuitive and impromptu, performing alone for the camera in a way that reflects upon the scale of a human body in comparison to the vastness of a landscape. This scale of existing as a small entity in a large world is depicted as a celebration in solitude despite living in a time that feels increasingly dystopic and polarized by the minute.

An obvious connection would be to the work of Cindy Sherman, but unlike Sherman, Squire doesn’t alter his own identity to create a persona but rather reveals the different personas and implications of a singular identity as a black man in the United States. Squire taps into the romance of photography by documenting himself extensively over the course of his life. There is power in translating how you see yourself, in your own many forms, into an image. No singular person can be representative of a whole, and Squire is the authority of his own identity deciphered through the historical and current experiences of living as a black man in the United States. He places himself in different landscapes and captures poetic actions that expand and contrast that create a timeline of his own identity. The self-portraits acknowledge his body that ages over time and is made visible through the years of repeated investigation, reverberating wisdom afforded by aging using his own visual language.

How long have you been taking self-portraits, and has your approach changed over time?

I began taking self-portraits in the early 1990s as part of my photography classes under Professor Steven Herrnstadt. These early self-portraits were aesthetically inspired by Bill Brandt’s domestic nude figures and John Coplans’ self-portraits, both of whose monographs I had found in a half-price bookstore in Des Moines, Iowa during that time. I took several classes with Herrnstadt which enabled me to grow quickly, and these early explorations naturally evolved into greater experimentation with my figure as well as the development processes of making a photograph.

I recall fondly the last year of my undergrad architecture studies when I had taken all required classes except for design studio and had a lot of free time on my schedule. I got permission from the lab director over at the journalism and mass communication building to access the lab on off hours when there were no classes. I loved the darkroom. I remember spending almost all day on Tuesdays and Thursdays in the lab scratching emulsion off negatives and using plastic sheets from bacon packaging as diffusers for varying effects with the enlarger. When I got to this phase of development the photographic process was driven by the simple questions of “What if…?” and “I wonder what that would look like?”. I felt alive just testing the medium. I think later I became obsessed with the way I was able to construct a persona on film that was drastically different than my normal self—particularly as I was inspired by the work of Cindy Sherman—and then work the printing process to de-architecturalize the setting (I was shooting in my dining room and garage), being inspired by the prints of Joel-Peter Witkin.

Most people that know me as an artist have no idea that the foundation of my practice is in self-portraiture. They see the current work and think it’s a departure from my studies of material culture when it is a return to self-portraiture after a 25-year hiatus during which I was honing that material practice.

How has your background in architecture and material culture influenced your photographic practice? Your work takes shape in many different forms, how does materiality drive your process?

Those are such difficult questions to answer, at least satisfactorily. I think my photography is better off if I don’t think of it being measurably influenced by, or somehow existing within the context of architecture, as I’ve been a bit of an agitator in that discipline. I once had a therapist tell me I had an uncanny ability to compartmentalize. So, it’s not necessarily something I spend time trying to unpack. And god forbid I start talking about ‘details’ and ‘structure’, or ‘the spatial intersections of architecture and photography’, of which I’m certain there’s much that can be said, blah, blah, blah. But perhaps that desired separation is all wishful thinking and part of my attempt to not center or privilege architecture in the work because the work—especially the “OUT FROM” project—is part of an attempt to free me from architecture’s clutches. Sheesh, now that I’ve opened that can of worms, I think I better say a couple of things that ‘matter’ in this regard, so to speak. Or, at least, let me take a crack at it.

The series of self-portraits that I’ve been working on the past three years—and the ones you’re most familiar with from the Aint Bad publication—explore a condition of unease that’s present in my sexagenarian Black body with the way the built environment has continued to thrive on concepts of materiality predicated upon extractive capitalism, at the heart of which is a continual disappearing of bodies like mine. So, the effort was intended to become invisible to the discipline in the most hyper-visible way possible. And being initiated at the outset of an unanticipated pandemic posed the real (non-academic) probability that I could be terminally disappeared.

That continuing project had been proposed in 2019 in my application for a sabbatical under the heading “Self Portraits on the Socio-Sexual Effects of Extractive Economies and the Material Geophysics of Race”, which is an over-the-top title I admit. But it was enough to earn some time and initiate work which led to serial attempts during lockdown to un-know both the prevailing systems of thought that had limitedly defined my Black body’s existence through the regime of labor as well as its concomitant centrality of a highly specialized form anti-Black humanist thought. And then you add the pandemic to the mix and the high-risk nature of my being within that context, and you get unanticipated urgency. So, it was an academic project that was pushed to the brink for fear that I might not make it through the pandemic.

So, that’s context. Now let me try to pull things together to answer the question of architecture and materiality influences in my photography.

My students and I have been exploring the “racialized global episteme of materiality” of which scholar Kathryn Yusoff spoke in her 2020 lecture at Harvard GSD, “Geo-Logics: Natural Resources as Necropolitics”. That lecture underlined an assault on humanity by a discipline of architecture that positions itself as a benefit to humanity. And because architecture’s racialized relation to laboring bodies of color has remained tantamount to the production of natural resource-based space, it is impossible—Yusoff argues—to respond to the overarching environmental crisis without first responding to the questions of racial justice. My work, then, documents a discomforted Black man engaged in an embodied study of imagining a way “out from” the discipline while remaining in it.

The imagery presents a hyper-visible but socially isolated dissent from the hypocritical humanistic social criteria which defines creative success. It purports the potential of my Black body existing as a ‘form of flux’ or ‘space-in-process’ (which thinking emerges in the writing of Tiffany Lethabo King in “The Labor of (Re)reading Plantation Landscapes Fungible(ly)”) which, then, because of the body’s ‘ungovernability’, it becomes of little value to ‘discipline’. As the portraits are set in the outdoors, the material landscape moves from its position as a mere architectural ‘entourage’, ‘backdrop’, or potential ‘resource’ for extraction to an open field prompting my reflection on other kinds of proximities and intimacies that my Black body might have to plants, objects, and non-human life forms in the effort to re-make myself and rebuild a relationship between what has existed above ground (architecture) and below ground (geology).

That’s probably cringe-worthily more than you were hoping for. At another time we can talk about my dust self portraits which is the first studio series of self portraits I produced early last year wherein the history of the camera as a material artifact became my focus. For that series, instead of being subject or object, I imagined myself to be a function within the camera attempting to materialize the otherwise invisible picture plane.

I’ve been following your work through Instagram and I’m curious how you feel about social media, and Instagram in particular, as an artist?

Social media is the classic example of a double-edged sword for artists. You’re damned if you do, damned if you don’t, to some degree. So, I think it best to make it work for you without thinking it’s an end-all. I think all photographers rather their work be experienced in exhibition or printed matter and not become prey to the death scroll. I try to figure out ways to make the work work off the screen.

Your work often considers duration of time, either referencing different historical eras, or the durational approach of creating photographs that reveal or conceal information. What do you think your work will say about you and the current era we occupy in the future?

I rather a historian takes a stab at that. I guess the work will for me always speak of the cruel optimism associated with my being a human—particularly an aging human—in this world, grappling with institutions that would otherwise dehumanize me. I think my use of the lens is something akin to weirdly being giddy watching the sunset. Now, I’ll leave others to unpack how all the works—the material works included—are equally self-portraits, and that there really wasn’t a 25-year hiatus.

Mitchell Squire is a multidisciplinary artist, educator, and curator. His practice encompasses the fields of architecture, visual art, Black study, and explorations of material culture. He is best known for his provocative teaching, his elegiac assemblages of found objects, and his poignant examination of the afterimage recorded onto the backs of law enforcement firearms training targets. Currently, and since the pandemic, he’s been engaged in the practice of self-portrait photography. His plein air self-portraits were recently featured in the 2021 Issue #15 of AINT-BAD Magazine, were featured in a 2022 solo exhibition at the Cecil R. Hunt Gallery at Webster University in St. Louis, and were the subject of his self-published trilogy of zines in 2021/2022 titled OUT FROM, LOUT, and WITHOUT LAW.

Squire has mounted solo exhibitions at Drake University (2005), CUE Art Foundation (New York, 2011), White Cube (London, 2012), Des Moines Art Center (2014), Bemis Center for Contemporary Art (Omaha, 2014), and the Cecil R. Hunt Gallery at Webster University. His work has appeared in signature group exhibitions at Richard Gray Gallery (Chicago, 2014), Lesley Heller Gallery (New York, 2015), Everson Museum of Art (Syracuse, 2019), Minneapolis Institute of Art (Minnesota, 2017, 2018, 2019), The Luminary (St. Louis, 2019), the Des Moines Art Center (2016, 2020, 2023), and Mattatuck Museum (Waterbury Connecticut, 2021). He has been an artist-in-residence at the Skowhegan School of Painting and Sculpture (2010), Ox-Bow School of Art and Artists’ Residency (2010), Banff Centre for Arts and Creativity (2013), Cannonball (Miami, 2014), and recently at the Sanitary Tortilla Factory (Albuquerque, 2021), and has been an invited participant in educational programs at The New Museum (New York 2011), Pérez Art Museum (Miami, 2014), and Museum of Modern Art (New York, 2015). Squire’s most recent curatorial effort was the co-curation of the timely and poignant Black Stories exhibition at the Des Moines Art Center (2020/2021).

Squire currently holds the position of Professor of Architecture at Iowa State University.

Follow Mitchell Squire on Instagram: @mitchellsquire

Douglas Breault is an interdisciplinary artist who overlaps elements of photography, painting, sculpture, and video to merge spaces both real and imagined. His work has been collected, published, and exhibited nationally and internationally, including at the Museum of Fine Arts Boston, the Czong Institute for Contemporary Art (South Korea), Space Place Gallery (Russia), the Bristol Art Museum, the Rochester Museum of Fine Arts, Amos Eno Gallery, and VSOP Projects. Breault has been an artist in residence at MassMoca and AS220 and was awarded the Montague Travel Grant to study in London and Paris in 2017. Douglas is a professor of art at Babson College and Bridgewater State University, and he has been a guest critic at MassArt, Wellesley College, Kansas City Art Institute, and the Slade College of Art, among others. Douglas is the Exhibitions Director at Gallery 263 in Cambridge, MA. He received his MFA from the School of the Museum of Fine Arts at Tufts University and a BA in Studio Art from Bridgewater State University, and he currently divides his time between Boston, MA, and Providence, RI.

Follow Douglas Breault on Instagram: @dug_bro

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

Earth Week: Aaron Huey: Wallpaper for the End of the WorldApril 26th, 2024

-

Earth Week: Casey Lance Brown: KudzillaApril 25th, 2024

-

Tara Sellios: Ask Now the BeastsApril 6th, 2024

-

ALEXIS MARTINO: The Collapsing Panorama April 4th, 2024

-

Emilio Rojas: On Gloria Anzaldúa’s Borderlands: The New MestizaMarch 30th, 2024