Photographers on Photographers: Gioncarlo Valentine in Conversation With Andre D. Wagner

The idea of the artistic canon is and will always be one of great controversy and debate. Whiteness has been the defining voice in appointing art and artists as important enough to be considered for entry, while Black artists and scholars have been the dissenting voice in redefining and reifying these very considerations. I think a lot about this figurative space of reference and reverie, where the greatest artists and luminaries of our histories gather to inspire and be honored. In defense of the canon, specifically the canon of beauty and meaning, Nikki Giovanni had this to say, “I’m not against the canon because if we give you a canon then you will vary on it.” In photography specifically, I think about how Black purveyors and storytellers have been largely blocked from entry into this larger context. In my mind, conversations about the importance of Larry Burrows, Danny Lyons, and Arnold Newman must include Louis Draper, Roy Decararva, and Carrie Mae Weems. Often, when I consider my own work, I find myself assured that the work I’m making today is not meant to be fully appreciated until many years down the line. But I have no doubt that my fully realized work will find a home in the canon.

Although Andre D. Wagner’s main focus is to do his work, the work of the now and the preservation of the now for the future, I have no doubt that he too will be lodged into the canon’s embrace, with or without permission.

Andre is probably the most important contemporary photographer working today. The “probably” in that sentence is largely sardonic in that any person who knows me knows that I believe he is singular in his import. Like me, he is both actively possessed by the need to document our history in a way that feels unchoreographed and honest, but also he is a forever student, consistently engaged in a dialogue with those great photographers that came before him, in and outside of his work. Although we are peers, I find myself to be a student of Andre’s work, a scholar even, having followed his career with a microscope since his arrival to New York in 2011. When LENSCRATCH reached out to me to participate in their Photographers on Photographers series and asked me who I would like to be in dialogue with, Andre immediately came to mind.

Being in conversation with another artist is one of the most important examples of Black History in context, as well as a way of identifying peers in the canon. The significance of these exchanges cannot be understated. I revisit Nikki Giovanni’s conversation with James Baldwin monthly, struggling to get through Baldwin’s refusal to allow Nikki space to speak. Toni Morrison’s opening essay in the first volume of The Black Photographer’s Annual is brief, but impossibly valuable in contextualizing the importance of the Black image, the Black every day, and the Black artist. Hilton Al’s writing about Dawoud Bey, Zadie Smith about Deana Lawson, all of these combinations create a powerful example of how mutual respect and dialogue can lift important artists of a specific time through history to pass along important messages, to measure our collective progress, and to preach the important word of the artist’s effect on history.

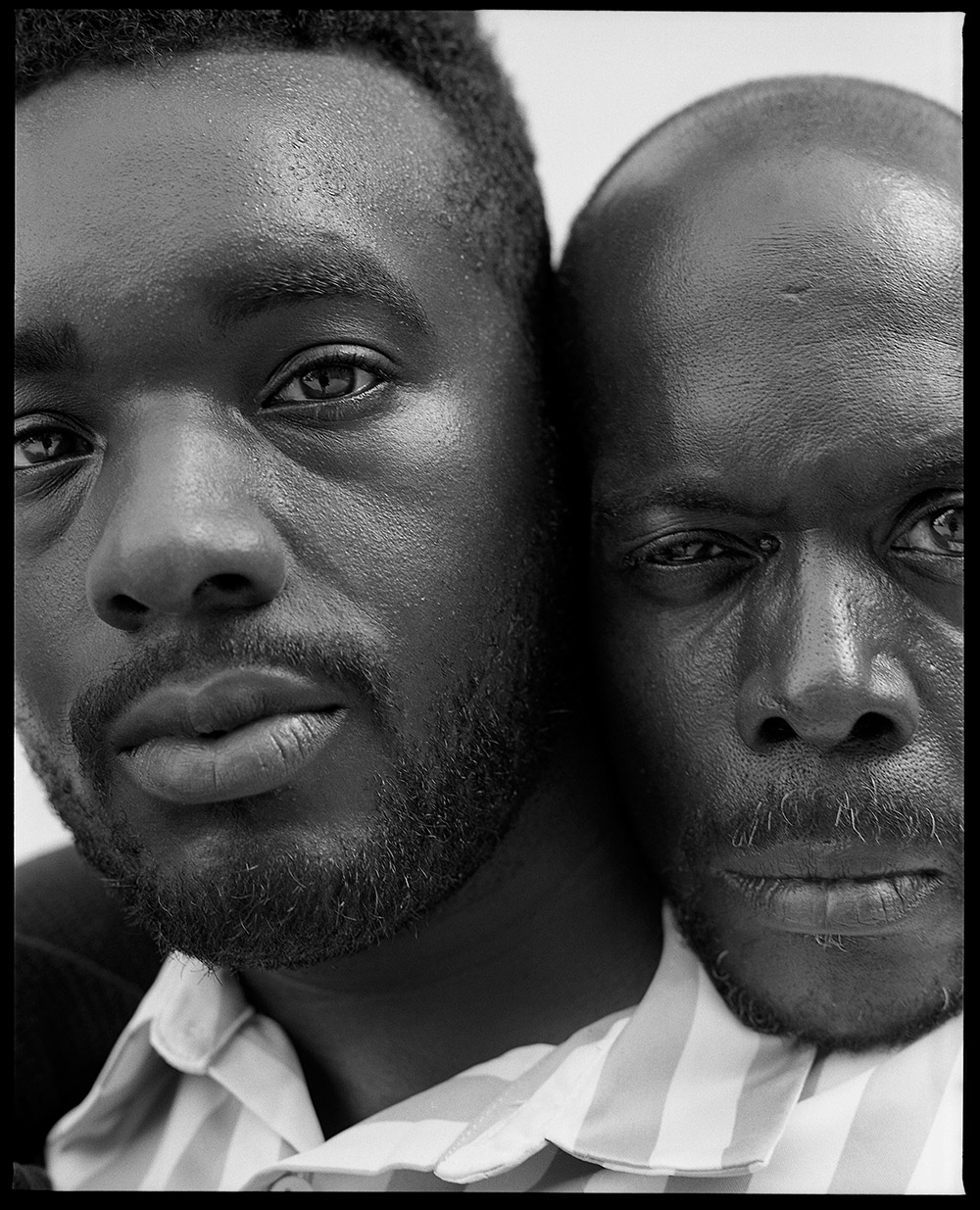

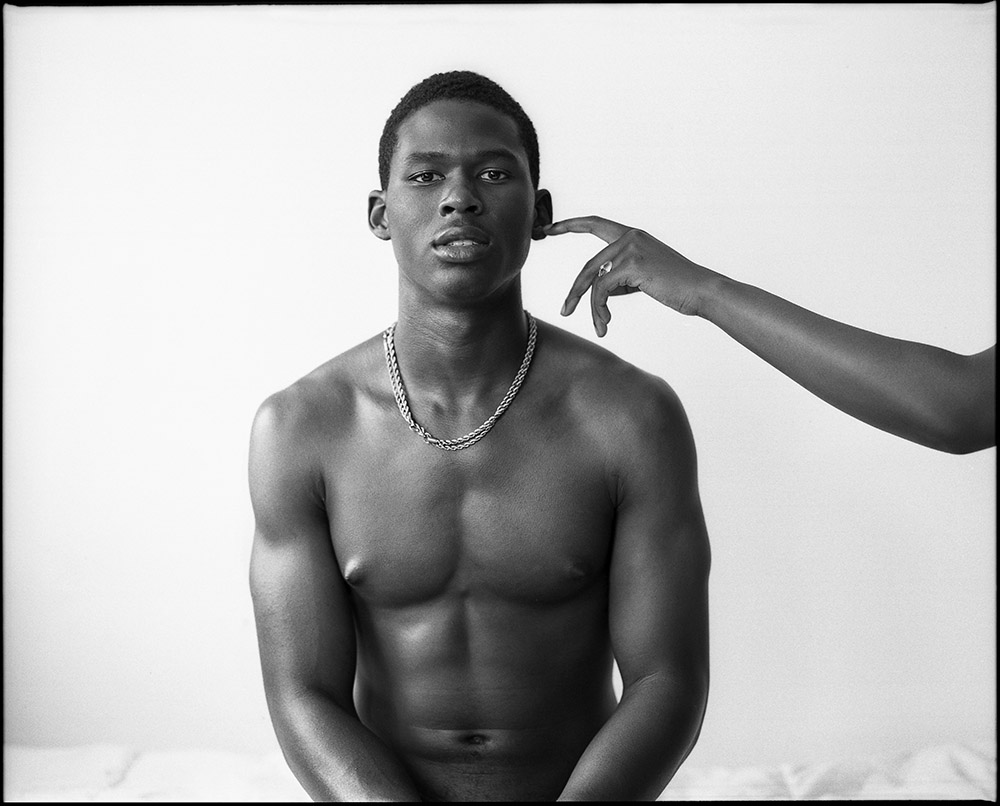

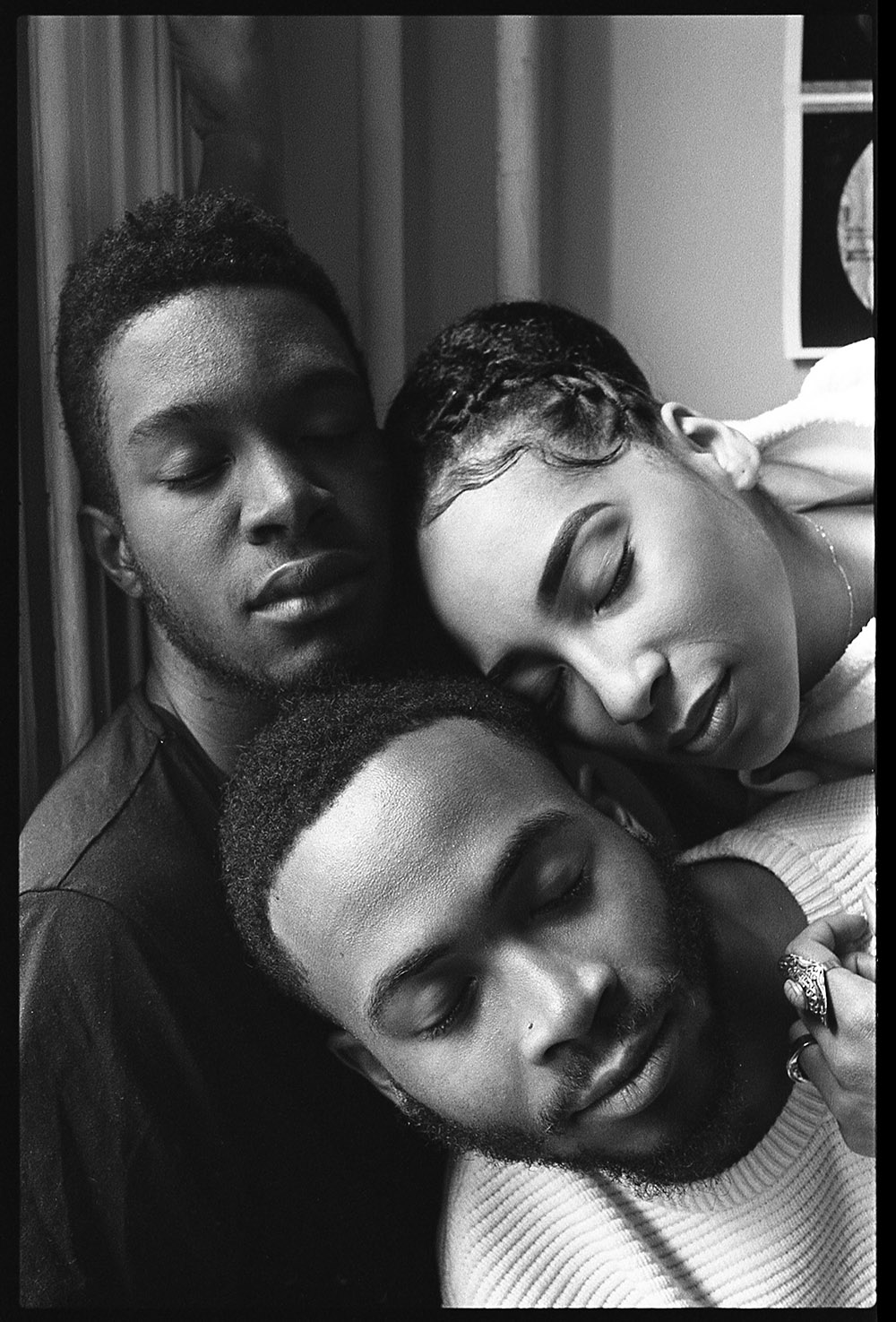

© Andre D. Wagner

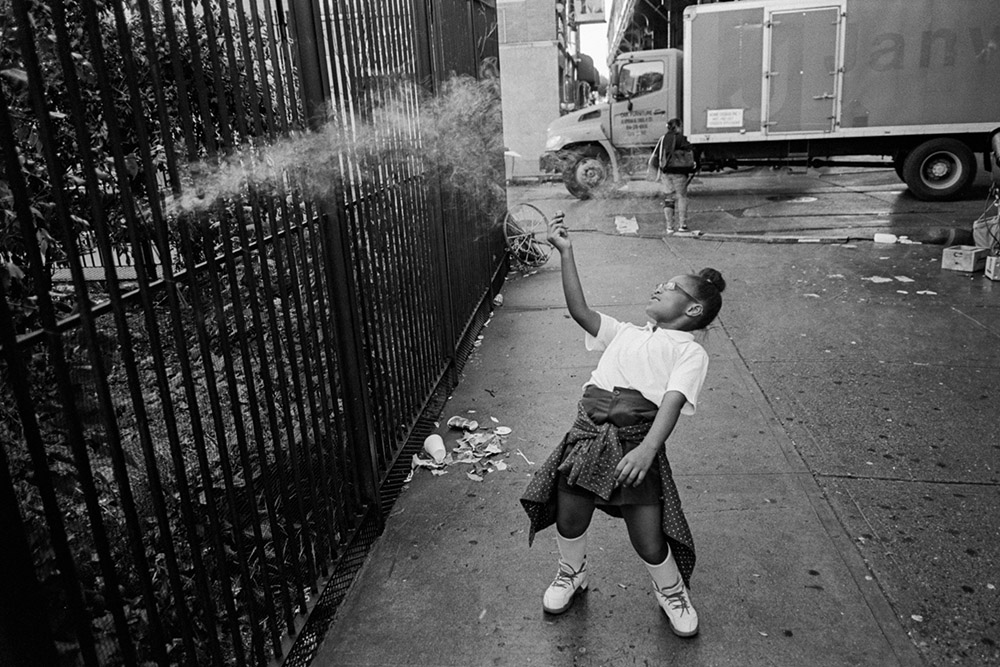

Andre D. Wagner is a photographer living and working in Brooklyn, New York. He explores and chronicles the poetic and lyrical nuances of daily life, using city streets, neighborhoods, parades, public transportation and the youth of the twenty first century as his visual language. His work and practice fits into the lineage of street photography that investigates the American social landscape, often focusing his lens on themes of race, class, cultural identity and community. He develops his own black and white negatives and makes silver gelatin prints in his personal darkroom.

His photographs have been commissioned by The New Yorker, The New York Times, The Cut, The Wall Street Journal, The Washington Post, WSJ, Time Magazine and Vogue, among other publications. For the movie Queen & Slim Andre photographed the iconic key art and the campaigns leading images. His photographs have appeared in a number of solo exhibitions and group shows in Los Angeles, New York and North Carolina. His first monograph, Here For the Ride, was published by Creative Future in 2017. He is currently editing a 7-year-old body of work titled New City, Old Blues, to be published in 2020.

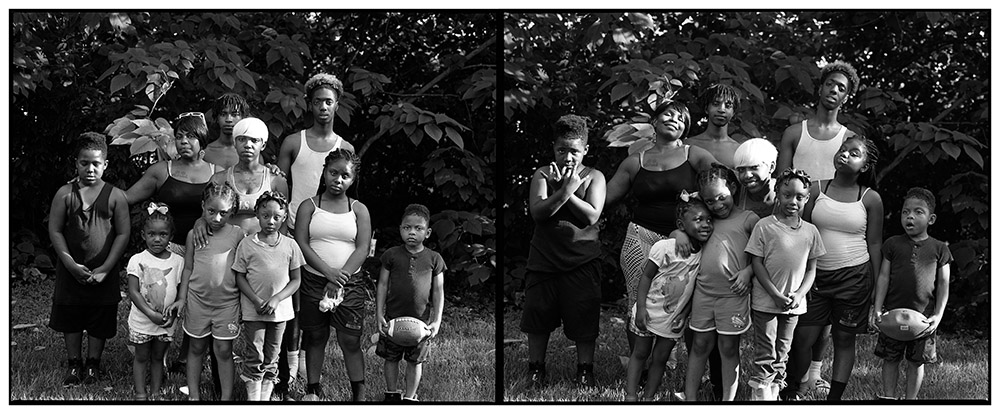

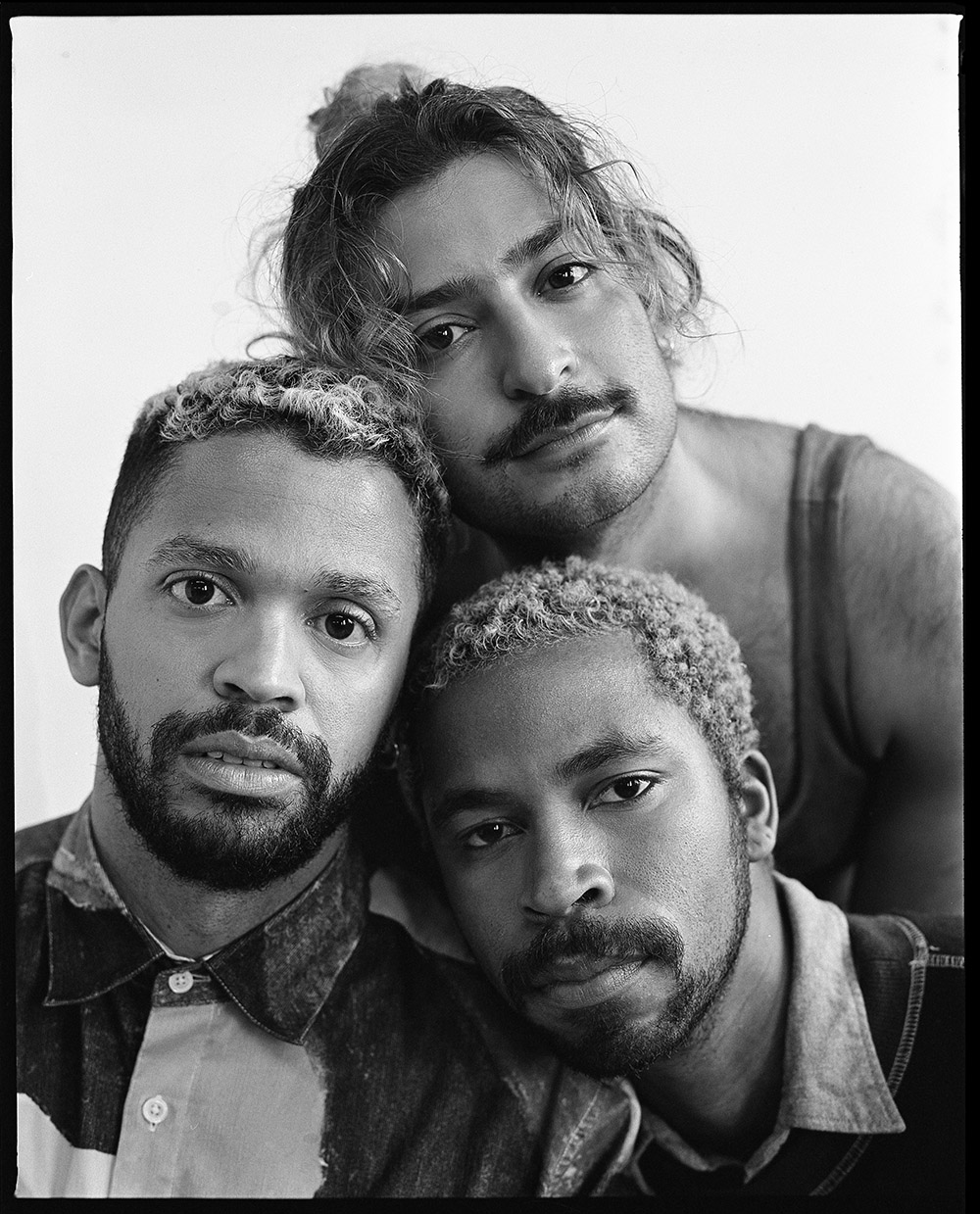

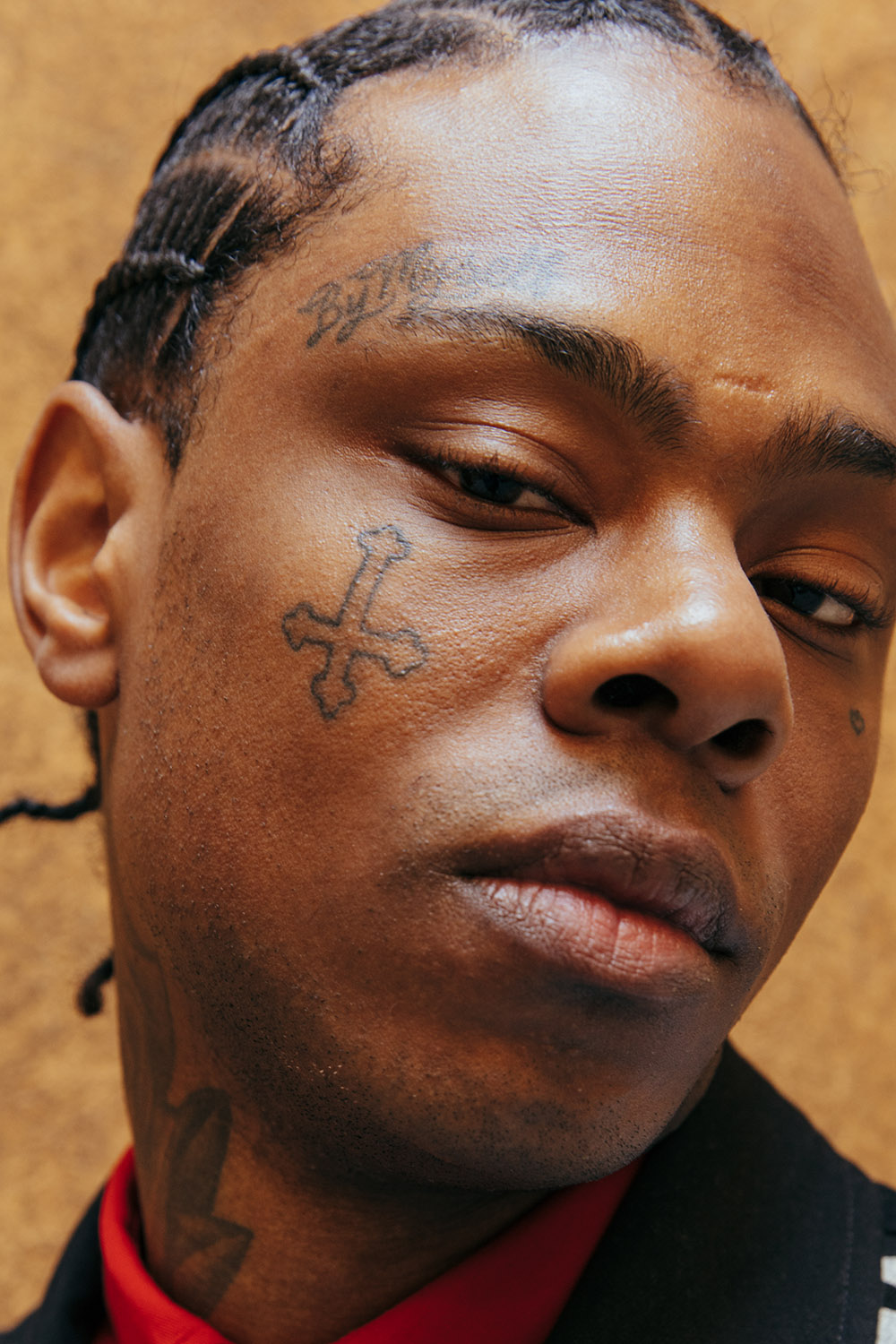

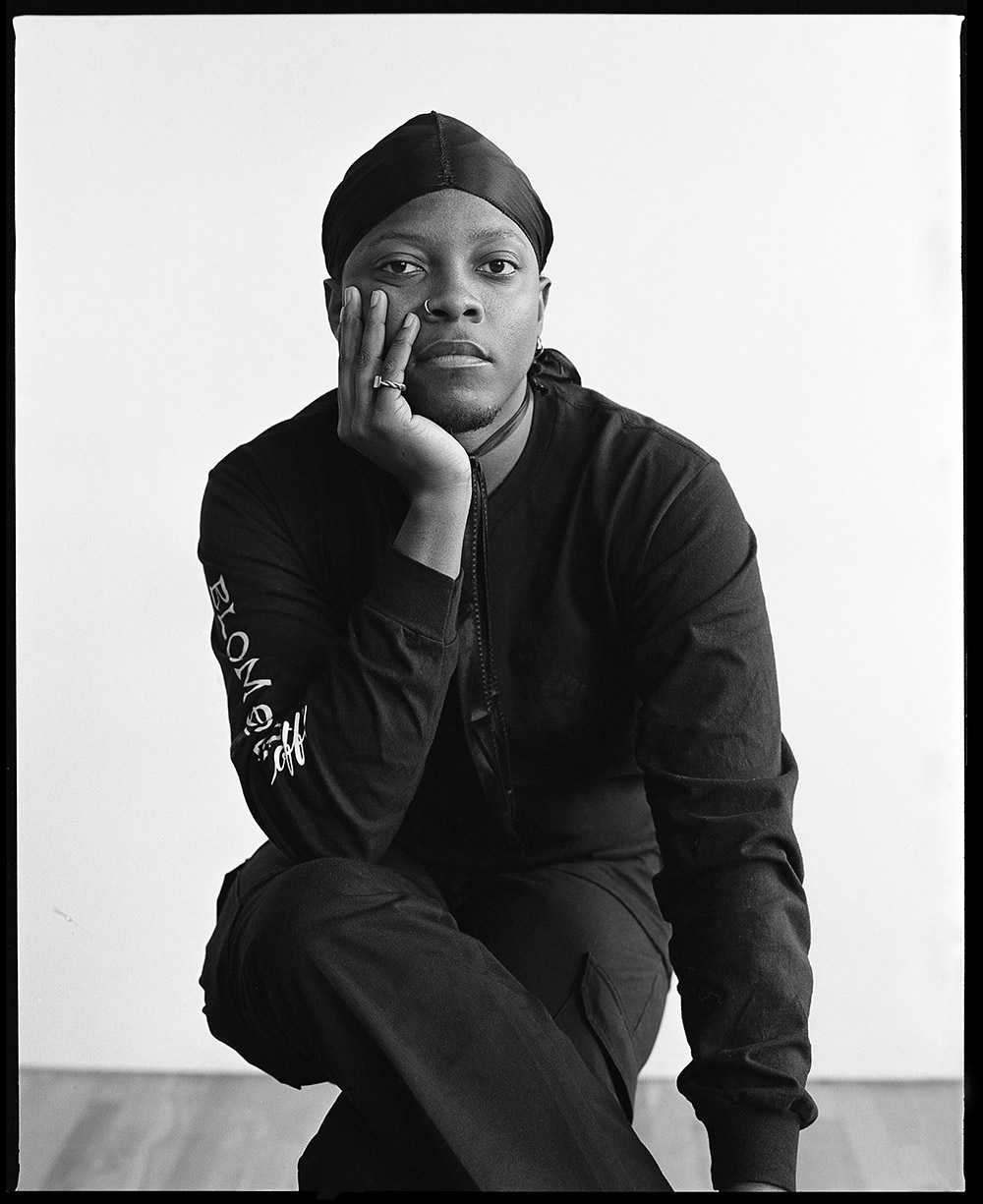

Gioncarlo Valentine (b. 1990) is an award winning American photographer and writer. Valentine hails from Baltimore City and attended Towson University, in Maryland. Backed by his seven years of social work experience, his work focuses on issues faced by marginalized populations, most often focusing his lens on the experiences of Black/LGBTQIA+ communities. Gioncarlo was a member of the 2018 class of Skowhegan’s School of Painting and Sculpture. In 2019 he opened his debut solo exhibition, The Soft Fence, at Blue Sky Gallery in Portland, Oregon. Most recently he was named a Visiting Fellow at the 2020 MDOCS Storytellers’ Institute and was invited to be an artist in residence at Twenty Summers this fall. He is a regular contributor to The New York Times and has been commissioned by Wall Street Journal Magazine, Propublica, The New Yorker, Esquire, Vogue, and Newsweek among many others.”

© Gioncarlo Valentine

© Gioncarlo Valentine

On Canons, Healing, and Doing Your Work: A Conversation Between Gioncarlo Valentine and Andre D. Wagner

Gioncarlo Valentine: Last year when I was working on my first solo show with the Blue Sky Gallery in Portland, OR, I worked on a catalogue of my project The Soft Fence. I wanted to have the images contextualized by people who I care about, but also whose names I’d like my work to be in conversation with and linked to in history. I chose Elliott Jerome Brown Jr. and Kiese Laymon. The latter’s essay (an extended version of it) went on to be published by The New Yorker. I thought of you for this conversation because your work is exceptional but also because I’ve always wanted our work to be in some form of conversation. Do you ever think about things like that, not just how your work will be remembered but who gets to speak about your work and who your work is in conversation with?

Andre Wagner: Yeah, for sure. I mean it’s not something that I think about a lot, but I do think about it. I study. You know what I mean? I’m a student of photography, and I think by being a student, naturally, if you’re also making work, you’re going to want to be in the same world as the people that you love and that have inspired you. There are so many photographers that I’m indebted to and so much work, so many people have paved the way. And so, I want to be part of the conversation, but I guess I just think about working more than anything and making work and just experiencing life. The whole art side and its historical context and being in conversation with people, it’s like yeah, of course. But only after hopefully I’ve done it until I can’t do it anymore. I’m still such a baby. I feel like I’m just getting started, so in a way all of that feels too grand right now. But shit, at the same time, what the fuck? I’ve put in a lot of fucking work. So, hell yeah, I want my shit to be all up in there and to be in every conversation.

GV: Same, I feel that.

© Andre D. Wagner

AW: Things have been aligning so far and I’m a believer in what I’m doing. I’m not trying to sit here and be overconfident, but I’m also not dumb. I literally came to New York with nothing and the way things have just continued to align in my life and to be where I am right now and this whole practice of photography is just based on faith. To me it’s all about faith.

GV: Miles Hodges and Zun Lee among others have contextualized the importance of your work. You have also written about other photographers like Garry Winograd, Robert Frank, and Roy Decararva. What about a photographer makes you feel moved to write about them? What do these photographers have in common?

AW: Shit, I haven’t written about a photographer in a long time.

GV: Which I guess could be a part of the question.

AW: I go through phases with my own writing, and I only recently started writing again, really. But I’ll say, maybe if I can switch the question up a little bit, instead of what makes me want to write, what makes me want to keep picking up their book after years of looking at the same work. Because it’s the same thing in a way. It’s like, yeah, I can write about a photographer, but every photographer you talked about me writing about, I also continue to pick up their books. They are the most used books on my bookshelf. They look battered. I love work that I feel like I can keep coming back to and there’s still surprises. It doesn’t die. It continues to feel so alive, and it continues to fill you with so much of whatever it is that you need.

© Andre D. Wagner

© Andre D. Wagner

GV: So, who have you been revisiting lately?

AW: Lately, I’ve been looking at a lot of Lee Friedlander’s work. I think it’s because of how I’ve been feeling over the past few weeks. Wanting to be out in the streets, making photographs like I usually do but instead, kind of just exploring my neighborhood. I’ve been looking at a lot of his work because, I mean he’s a master, and he’s made photographs of so many different types of subject matter. So with me wanting to make different kinds of work, I’m looking at different stuff that I haven’t necessarily taken deep dives into before.

GV: What do you think that Lee Friedlander and the other photographers that I mentioned have in common?

AW: I think I relate to photographers that really work at it. These photographers just had …they really worked at it. I think I also have that working spirit and mindset and I think that gives me something to chew on and continue to chew on. Like yeah, in this moment I don’t want to be running the streets in the middle of crowds taking pictures, but I’m still picking up my camera and taking pictures every day. And it’s just like that work ethic of still just trying to figure it out. Just because I’m not making a picture that people might know me for doesn’t mean I don’t make all these other kinds of photographs too. And I’m working out other things that I’m interested in. Those photographers continued to work no matter what. Robert Frank went from making photographs to making films because he had the heart; he needed to say something. I don’t know. I love artists like that, that continue to try and find ways to speak but through working, not just trying to sit around and come up with the fucking best idea ever, because my brain doesn’t work like that. I find out all of these interesting things through making photographs.

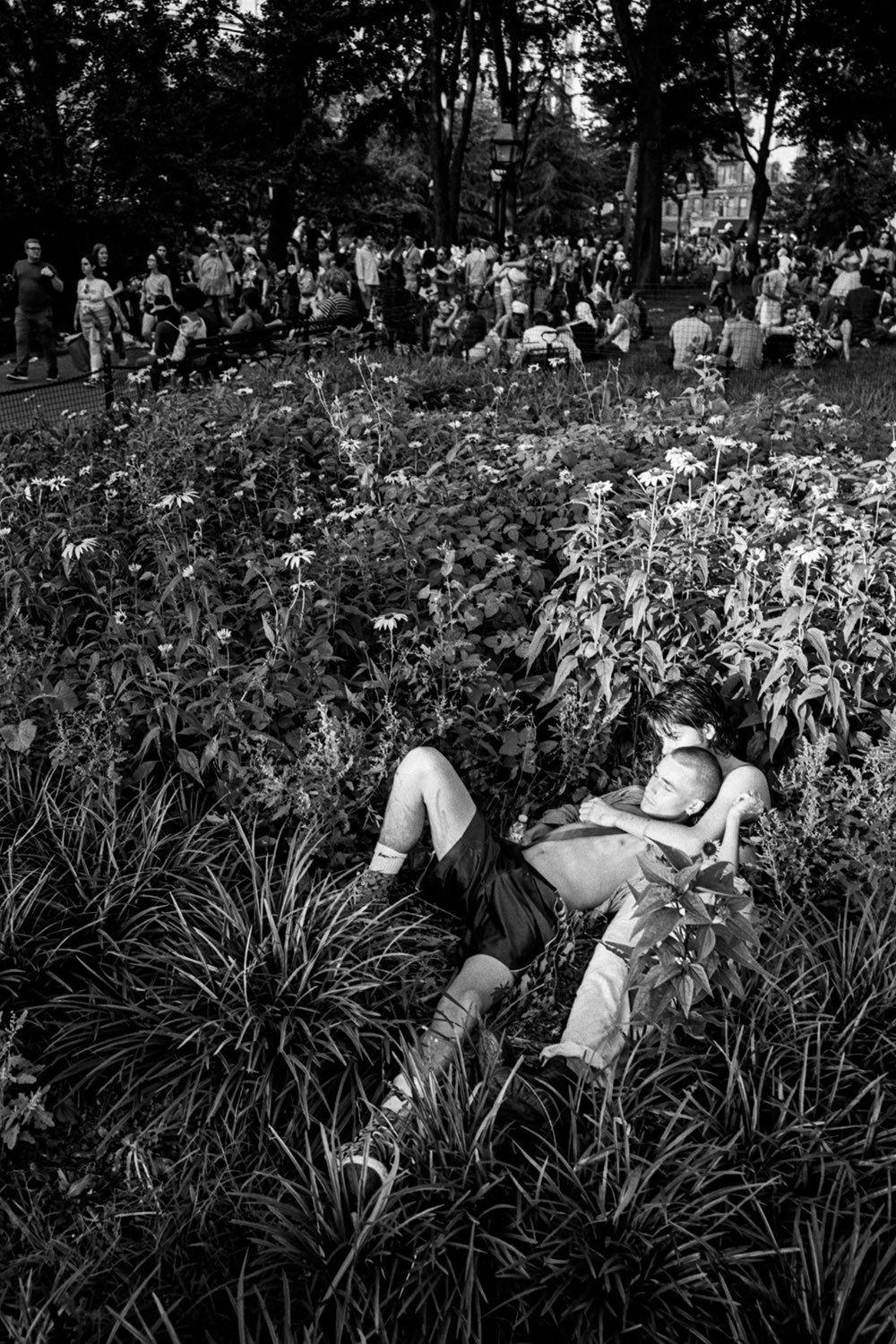

© Gioncarlo Valentine

© Andre D. Wagner

GV: So, you wouldn’t consider yourself a series-based photographer.

AW: I don’t come up with a series beforehand. It’s kind of like they just happen, because I’m always just taking pictures. For example, I have this random series right now that I’m working on. It’s like six years later. I’m always running into photographers, because I’m always out shooting. And I always like to take pictures of photographers just because. I didn’t think about it like I want to go and do a series on photographers. Obviously, there’s plenty of artists that went out and documented artists, but this just happened naturally. And then I started to see the pattern, now when I do see photographers, I’m consciously making images for it. Let’s talk about you. What about you? What work have you been working on since the start of 2020? This year has been so varied in experiences, and you’ve been traveling. And now you’re back, and you’re in the Bronx. And you got all this equipment, and you’re printing. And there’s a lot going on, so what kind of work have you been working on this year? What have you been thinking about?

© Gioncarlo Valentine

© Andre D. Wagner

© Gioncarlo Valentine

GV: So I started shooting a portrait series last year and kind of editing through that has been tough, because it’s just not anywhere near where I want it to be. I’m not really a series-based photographer either. Editors will always come to me and ask me to send them projects that I’m working on, new bodies of work, and I regularly disappoint because I don’t work in that way.” It has to become a thing, so I make a lot of portraits of folks that’ll eventually become a thing.

AW: See, (laughs) we’re speaking the same language.

GV: (Laughs) But I would like to learn the discipline of being a series-based photographer. It’s such a brilliant way to work. I know it has its challenges and limitations but the grass seems greener. So I tried that with this series and put some of the portraits together. They just feel very empty. They feel pretty but hollow.

AW: Because you came up with the idea, and then you went and did it?

GV: I don’t know. Maybe because it’s just empty right now. It needs more interior space and less isolated studio space. Now I’m thinking about how to make the work stronger. I’ve been writing a bit, I wrote a lot during the first few months of “Ms. Rona” when I was in Hawaii. I’m in a fellowship which has been fabulous and time consuming. I just bought an inkjet printer, so I’m learning that trying to get a decent black and white print feels like a nightmare. That’s really all I’ve been doing, outside of my weekly “we’re in the early stages of the apocalypse” panic attacks, just spending time with the work that I’ve already made, taking commissions and making personal images.

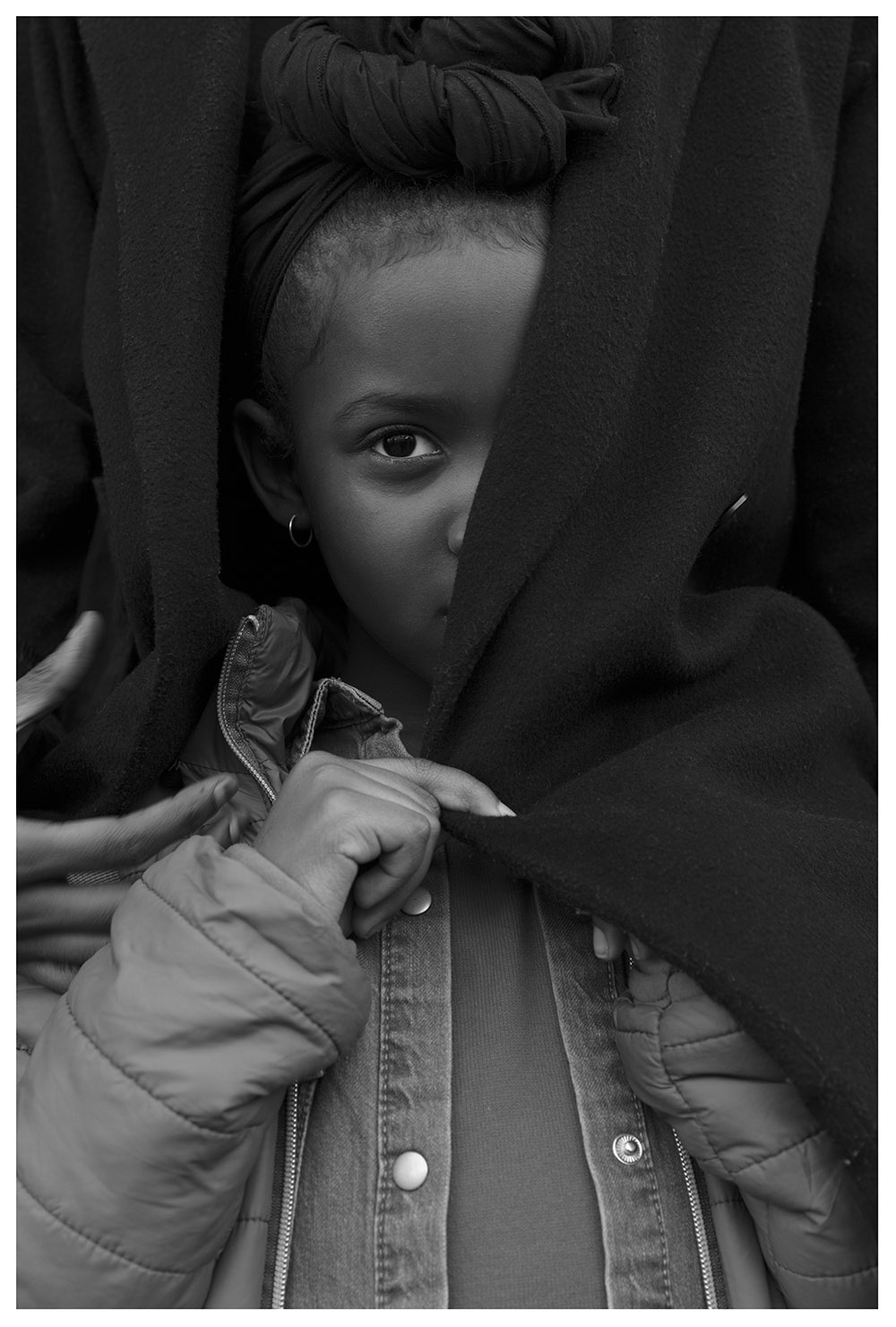

© Gioncarlo Valentine

© Andre D. Wagner

© Gioncarlo Valentine

AW: That’s an interesting thing, the terminology you just used, making personal images. What do you think about the state of photography right now and how photographers operate and how people have to make a distinction? You kind of have to say you are doing personal work, or you’re doing this other kind of work. To me, photography is personal work. And yeah, I love to do some commissions, but it’s like that’s not why I’m taking pictures. And it just seems like nowadays photographers only want to do commercial work. And so, I guess the question is, what do you think about that, in 2020, all these lines are blurred and it doesn’t matter if you make commercial work or if it’s in a gallery, because it can end up in both places anyway. You know what I mean?

GV: I think it’s like you when you use the language of “street photographer.” That term doesn’t really encompass your full body of work, but it’s kind of a catch all, something people can understand and a title people project onto you most notably. When I think about the future monographs and the books of my work that I’d like to make, a lot of it is assignment-based work. But it’s also personal work. So I do think that they’re all in the same conversation. I know that all my work is personal, but I think for the sake of people, it’s important to differentiate. But I also think for yourself it’s important to be like this is work that I’m making for myself. I’m not being paid to make this work. I had an idea, and I went and did it. There is merit to that line being drawn, because there’s a difference between getting up to shoot something that you conceived of, that you had the idea to do with no money coming your way and then something that you were paid to go do and access that you were given. So, I think that the distinction sometimes is important.

© Andre D. Wagner

GV (Cont’d): I do know, though, that in 2020, the lines are unfortunately really blurred. And I don’t necessarily like that they are. I like some definitions. One of my biggest regrets and struggles as a photographer has been a lack of intentional mentorship. I have asked so many great photographers who I’ve been privileged to know, to actively and intentionally mentor me because mentorship is serious, it is not something to be entered into lightly. And no one mentored me as a photographer. I learned and continue to learn what I can from stories and conversations with legends. People like Renee Cox and Eric Johnson have allowed me to look through their archives and to use their studios. But the great undertaking that is mentorship is something I have yet to experience. Have you had active mentors?

AW: That’s a great question. I was literally just talking about this exact thing with my wife the other day. Obviously right now, all the editors and folks in the photo world are talking about Black photographers. They’re trying to hire Black photographers and see which Black photographers are out there. But the problem is so multifaceted. It’s a constant battle. For so long Black photographers didn’t get opportunities because of economics, the entry level, you know what I mean? Black people weren’t getting into art schools, there weren’t that many of us assisting. There’ve been so many levels and barriers to entry. And because so many Black photographers don’t have all these opportunities, we’re not in the same spaces and we’re not the people getting recommendations. And so now everybody is looking for Black photographers, and it’s like you want all these photographers that are at this crazy level. But many of us haven’t had opportunities to get there. Black photographers aren’t getting called back if you have one bad job, you know what I mean? Where white photographers do. There’s all these things, and then like you said, going back to mentorship, I never had a mentor and I’ve always felt like coming up into this industry trying to figure out what to do, how to make work, or an example of somebody that you can ask questions or help you with contracts. There’s all of this, all of these things that you need to know. And yo, I never had that as well, and I had to learn a lot of things the hard way. And it sucks, because it’s like yeah, shit happens, and you realize you got underpaid, or this fucking contract is fucked up. Or you mess up on a shoot and it’s your first time having a client. Now that client is never going to call you back, because they’re not happy with it. Black photographers need to be cultivated. They need to be invested in. They need opportunities as well, and it sucks when you feel like you don’t have a chance to fail. So I feel you in that way, feeling like you never really had that mentorship. I would’ve loved to have that as well. And I’m still trying to figure shit out constantly.

GV: Is there a reason that you feel like you didn’t have mentorship, outside of not going to school? Do you think there was anything else?

AW: I never necessarily reached out for it. I mean, yeah, I’m sure early on when I just started photographing, I probably emailed photographers that I loved, just like all of us do, saying, “Hey, I would love to assist you.” But seeking out serious mentorship, I don’t think that’s something I really ever did. So part of it is probably my fault, but it’s like at the same time, once I got information and knowledge on how things happen, I was already kind of on my way. You know what I mean?

© Andre D. Wagner

© Andre D. Wagner

GV: So do you consider yourself a mentor?

AW: No. I’m just a loner out here making pictures. I’m not engaged like that right now. And I’m not saying that I won’t ever be, but man, I’m just so selfish with my time. I’m making pictures. I’m in my dark room. You know what I mean? I got to see my wife, and I do other things. I’m just like I’m really obsessive, and so I’m not mentoring anybody.

GV: As this conversation is happening, protests for Breonna Taylor, George Floyd and many others whose lives have been snatched by state violence and white supremacy, are breaking out across the country. We are also five months into a global pandemic that has killed over 150,000 Americans and over 700,000 people worldwide. What do you think your responsibility is as an artist making work right now?

AW: Just to be true, to be truthful. Like Nina Simone said, our job is to reflect the times. And I feel like that’s true of me always. Sometimes that’s my annoyance with moments like this, not necessarily with the moment, because we need this moment. But I feel like so many artists, whenever something happens, they suddenly get these grand, profound meanings in their works. And it’s just like, okay, but I already felt like this yesterday, so that shit annoys me. Like, how are you going to speak about this shit right now, all of a sudden you want to deal with what’s happening? It doesn’t work like that. And that’s not to point a finger at anybody. Obviously our medium of photography deals with the world in a way that no other medium does. But I’m more so talking about the mindset of the artist. The work is always supposed to reflect the times. It’s always supposed to be true. So even when I say I’m making all these different kinds of pictures, it’s always soul searching. You know what I mean? And that soul searching is done through living in the world. And so right now, with the protests and everything, naturally I started to go photograph and work with it very directly. But then I couldn’t do it, I just started feeling really drained and empty. I didn’t have it in me. So it’s been kind of liberating in a way to be able to actually listen to myself and kind of just go down a different path in the midst of everything right now but to know that I’m not turning my back on it. I’m still trying to figure out how my work continues to evolve. It’s like all this shit is happening. It’s sad, man. And yeah, I don’t know how you can be an artist and not make work about what is going on, honestly. I think this shit deals with all of us. What about you?

GV: I don’t know. I’ve done a lot of work. I used to organize. I’ve marched in dozens of protests. I’ve put in a lot of time, so I don’t necessarily feel the same amount of guilt as other people who are choosing to sit these current protests out. Also, in and outside of my work, I’m constantly trying to be a part of this conversation. In writing, through photography, how I use what small platform I do have. I’m always mindful, always thoughtful. I learned in my social work days, long ago, that there are so many important roles to play in this battle for Black liberation. Toppling white supremacy is not restricted to the streets, but protesting is an invaluable part of this battle. Right now looking at myself, my actions, and writing about this time, feels like where I need to be. But sitting quietly, resting, crying, and talking is also enough. I did feel like shit for missing the Black Trans rally the other day at the Brooklyn museum. It was difficult not to be there, but I know what’s best for me. I know what my mind and body has been telling me. How have you been finding healing and restoration after walking the streets of New York and documenting such a chaotic reality?

© Gioncarlo Valentine

AW: That’s what I’ve been trying to figure out over the past couple weeks. I’ve been trying to pull back a little, I’ve spent so much time just kind of going, going, going constantly. I’ve been trying to walk a different beat and not beat myself up. I’m still taking tons of pictures, but I’m being lighter on my own spirit and on myself and really trying to take it easy and enjoy the days. Trying my best not to stress myself out. I feel like the way that I usually make pictures is very physical. I’m always trying to stand in the right spot. I’m dealing with people and different energies and suspicions and all of this. And yeah, it can wear on you. When COVID hit I was riding a bus around Brooklyn and seeing Black construction workers or people doing yard work. I felt that there were pictures that needed to be made. I felt that nobody was roaming around my neighborhood seeing all these black people that’s still got to be out here working or getting groceries for their families and doing what they need to do. And I feel like my medium is so perfect for the situation in a way because I don’t necessarily need to be up on top of people. But photographs just provide a certain type of evidence that’s undeniable. But at the same time, you can still make something that’s not only about a cold fact. And so all of that is stressful, and you’re dealing with real people, people that you don’t know from all different walks of life. So yeah, I just been taking it easy.

GV: Where have you been finding joy during this time?

AW: I mean man, I don’t know.

GV: Actually, I’m going to challenge you to think a little harder about that.

AW: I’ve been having a hard time. I’m not going to sit here and make it seem like I haven’t, that I’ve been able to find joy every day. You know what I mean? Because I definitely haven’t, but I mean I don’t know, man. I’ve been ordering a bunch of books and they’ve been bringing me joy.

GV: Come on, books!! Who’d you buy?

AW: I’ve been buying some Lee Friedlander books, picked up a couple of Henry Wessel books, a republishing of Helen Levitt. Who else? What else did I buy? Jules Allen came out with another book, Good Looking Out. So yeah, books have been important. What are you looking forward to this year?

© Andre D. Wagner

GV: Well, this is my 10th year as a photographer. I picked up a camera 10 years ago in December. So the point of the whole year for me was actually to slow down and reflect. I planned to get my hard drives in order and to make sure that my work was organized. I also wanted to write more about my work. Then Covid-19 happened and George Floyd, Breonna Taylor, and Sean Reed happened and I’ve been having a lot of trouble sticking to that plan. But I do want to sit with 10 years of doing one thing and see what that means. What does that look like moving forward, kind of building on that. I turn 30 this year too, and I’ve been talking about this with my friends a lot lately. I’ve never had a life of celebrating things. I’ve never celebrated birthdays in large ways, and I just don’t celebrate shit. But I think about my friends when I tell them about an accomplishment that seems kind of regular to me, they’ll be like, “You should throw a party.”

AW: Celebrating your accomplishments doesn’t cross your mind?

GV: It doesn’t. I never even consider it. But there have been moments where I have done myself a disservice by not sitting with an accomplishment and celebrating it actively. Not just me being like damn, I did that, but allowing a day to honor it. Lately I’ve been buying my friends flowers and books, and writing letters and realizing, bitch, I want flowers. I want letters. I want to feel that. I want to feel thought of by someone. I want to feel like these accomplishments that I am treating like every day fare are things I should stop for. And I think that that’s a big part of this year. And it just so happens to culminate with me turning 30 and my photography career turning 10. But yeah, I’m really serious about that. I really want to have a more celebratory life.

GV: So to close, just for the sake of levity, tell me a fun fact about you that no one knows. But don’t give me no dumb fun fact.

AW: A fun fact? Give you Kawhi Leonard, be like I’m a fun guy.

GV: I have no idea who the fuck that is.

AW: A fun fact about me?

GV: I‘m not playing with you.

AW: You go first.

GV: Well I don’t know if it’s a fun fact. People are always interested in the fact that my favorite shows are Buffy, Seinfeld, and Frasier. I find people really do take joy in knowing this strange fact. Because of my pro blackness, it feels, for a lot of people, like you can’t endeavor towards white sensibilities in that way.

AW: Well I think for you especially. Nigga, come on?

GV: But in reality, it connects me to my childhood in a major way. And it also, I don’t know, I think that there’s a lot of lessons to be learned in all three of those shows. They still hold up for me, even with all the things I know about whiteness and white supremacy.

AW: My fun fact is that I hardly even watch TV.

GV: That’s not a fun fact. That was wack, and you tried it.

AW: It’s a fun fact.

GV: Most people don’t watch TV, Andre.

AW: You do, you just said. My other fun fact is I just learned how to shuck oysters. I’ve been eating oysters at the crib.

GV: What is that? What is the shuck?

AW: To open it, to open them up. It’s called shucking them.

GV: Well shit, that’s a double fun fact.

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

The 2024 Lenscratch 1st Place Student Prize Winner: Mosfiqur Rahman JohanJuly 22nd, 2024

-

Ellen Mahaffy: A Life UndoneJuly 4th, 2024

-

Julianne Clark: After MaxineJuly 3rd, 2024

-

Kaitlyn Jo Smith: Super8 (1967-87, 2017), 2017June 30th, 2024

-

Katie Prock: Yesterday We Were GirlsJune 27th, 2024