América Latina Week: Alejandra Aragón

This interview was written with the kind help of and in conjunction with Elena Gálvez Mancilla – Mexican historian and sociologist; a researcher on the Amazon and indigenous culture, interested in the image as a historical source, photography enthusiast and environmental activist. The post is featured in both English and Spanish. The Spanish version follows the English.

When I was selecting 5 Latin American photographers for this week’s project, I thought about the continent’s diversity. I wanted to go from the uppermost northern territory to the southernmost location. For the first feature of América Latina, I have selected Alejandra Aragón. She comes from México, Ciudad Juárez. This is the cite where artists like Teresa Margolles have developed many projects around migration, violence and social transformation. This city borders the United States, identity is driven by many forces. Aragón questions this placing with the analysis of public and intimate violence and its consequences in the population’s psyche. There is a certain subtlety in her photographic work, it navigates representation with balance. It does not create a morbid spectacle, nor does it hide real issues – it creates more questions and encourages the transgression of textual and visual communication.

©Alejandra Aragón

Alejandra Aragón is from Ciudad Juárez, México and holds a degree in Visual Arts and Business from the Autonomous University of Ciudad Juárez (UACJ). She was part of the Photography Production Seminar of the Image Center in México City in 2017. From 2013-2020 she participated in several group exhibitions throughout Mexico and Europe. Her documentary film Invisible Nights was part of the “Coordinates” program of the Ambulante Film Festival in 2018. She was awarded the Mexican arts grant (FONCA) in 2019. She is part of the Joop Swart Master Class 2020 and is a recipient of the 2020 NALAC’s Border Narrative Change Grant. @aleprendelaluz

Through a multidisciplinary process using video, audio, photography and found images, her work explores how the territory determines the experience and identities of the border regions from a decolonial transfeminist standpoint.

¿How did you start doing photography?

It occurred when I was 21 or 22. In Ciudad Juárez you can only work in the city’s assembly plants. I come from a precarious environment and my only goal in life was to make money and help my mom. So I did work in a factory until I was 27. However, when I started a film workshop I realized I wanted to dedicate myself to art. My objective was to create films at first but when a friend of mine gave me an SLR camera, still photography became a more accessible path to practising the basics like composition, light and technical abilities. I did amateur photography for years. In fact, La Guerra was put together by going through compilations of photos that I did when I was just starting.

©Alejandra Aragón

Who are the artists that have had a strong influence on your work?

I have had literary influences. In La Guerra, I refer to Arminé Arjona, a poet from Ciudad Juárez. Autoretrato Premonitorio stems from Marguerite Duras’ The Lover. I like the idea of producing intertextuality, artistic production is a compilation of all of the elements that we have absorbed from the world, armed with all the images that make you up. Thus, through reading, Elena Garro surges with the notion that “violence stops time” and Cristina Rivera Garza provides elements to talk about scribing from the body. Regarding photography, I was always gripped by Melba Arellano, how she portrays her subjects and what was intended with a color pallet.

The classics too, Maya Goded, Graciela Iturbide, Tina Modotti and Lourdes Grobet.

One must consider that only ten years ago, before social media and Instagram there was very limited access and visibility to women’s work. So, I took from what I learned in books, magazines and the few opportunities I had to visit exhibitions.

¿What is the most important part of your practice and how do you develop your creative process?

The artistic process develops from every artist’s intuitions and interests. For me, the most important aspect is my situated experience; to approach art from the condition of my body and identity. Then comes the importance of research in order to find the best strategies to address particular topics of interest.

When I worked on La Guerra, which is a compilation of my early work made between 2008-2013, I did it through the revision of my own archive. I was not aware of the value of my images until I learned the value of the archive and the intuitive naïve nature in which I was able to document such an extraordinary event in a very personal way. I began noticing patterns, how the indoors connected to the outdoors, leading towards the relationship between the intimate and the public. Both portrayed different modes of violence. This process helped me come into terms with my own experience of those violent times and their effect on my mental health. It allowed me to grasp a better understanding of the deep repercussions this war has had in Mexico’s population. It is evident, we live under post-traumatic stress, a depressive state submerged in alcohol. I had a political awakening during those years but it was only after many years that I was able to see my photos from a different perspective. The nature of the project and the process also gave it its diptychs form.

La Pinta is especially interesting to me because of its colour. ¿Could you comment on the process?

All which acquires a pink or magenta tone is the result of a negative with a sensitivity to the infrared spectrum of light. Thus, everything that’s green reflects the infrared spectrum. For the Vine a la Pinta project I decided to make sense, deliberately, of colors generated by this film, as a metaphor that reveals an invisible spectrum of reality. In this case, the binary structures of gender. It is what I think is hidden in the background of different constructs of hegemonic masculinities such as those built from the culture of my very Mexican family, of absent parents, the paternalism of the state whose decisions displaced entire communities. In that order, these structures are also at the base of the drug trafficking phenomenon. It is nowadays one more way in which men, especially young, precarious, racialized, boys affirm their powers to achieve the hegemonic ideals of masculinity.

I am currently working on a photo book for this project, which will also be featured in an exhibition next year in the Rubin Center for Visual Arts on the other side, in Texas.

©Alejandra Aragón

©Alejandra Aragón

¿How can we represent violence?

I believe we are in a strange moment when it comes to the representation of violence. It is a consequence of the remarks from these last 10 years by phenomena like the war against drugs and the circulation of images on the internet. On the one side, there are horrific spectacle images that seek morbidity for consumption purposes. On the other hand, there are practices that aestheticize and generate an erasure or depoliticization of the violence they are trying to portray. The latter as a consequence of the criticism of the former.

I do not know what is the best way to represent violence. I personally liked what Tatiana Huezo achieved in “La Tempestad”. She uses particular resources: focusing on testimonies, using the landscape as metaphors, avoiding the display of victims to deny the possibility of re-victimizing their bodies. It comes from empathy and caring for others. Those are some of the examples, that I’ve been able to identify, that achieve balance and do not reproduce violence nor aestheticize it. Well, I do not have a better answer. I do not know, I am also trying to discover this.

How does migration affect your work?

There are paradigmatic topics associated with borders, migration is one of them. Hence, I am not extraneous to it. I part from my situated experience. It is from my own territory that I address migration, and make the distinction between displacement and migration because they are different from each other.

We are all migrants in Ciudad Juárez. Everyone comes from a different place or passing through, whether that be now or 30 years ago. So, I feel that I can share that condition. There are as many forms of migration as are bodies traversing territories. Vine a La Pinta… is one of them. I tackled this topic from a historic perspective, from the memories of a family like my own that have never stopped migrating. It is relevant to clear out two distinctions: on one hand, we are a wandering species, we migrate, geopolitical boundaries are absurd. On the other hand, in contemporary history migration is actually forced displacement, a result of a neoliberal precariousness.

Other times I am involved in briefer projects, as a required answer to the urgency of the situation. Last year I covered a story on women and Respetrrans children Respetttrans: El lugar sin límites. | Hysteria in order to raise funds for the LGBTTTIQ migrants’ home/centre. These are the most vulnerable groups of such an extraordinary migration phenomenon, the one that we saw happening with caravans of Cubans and South and Central Americans. It was necessary to make it visible due to the urgency of a matter that has become a humanitarian crisis.

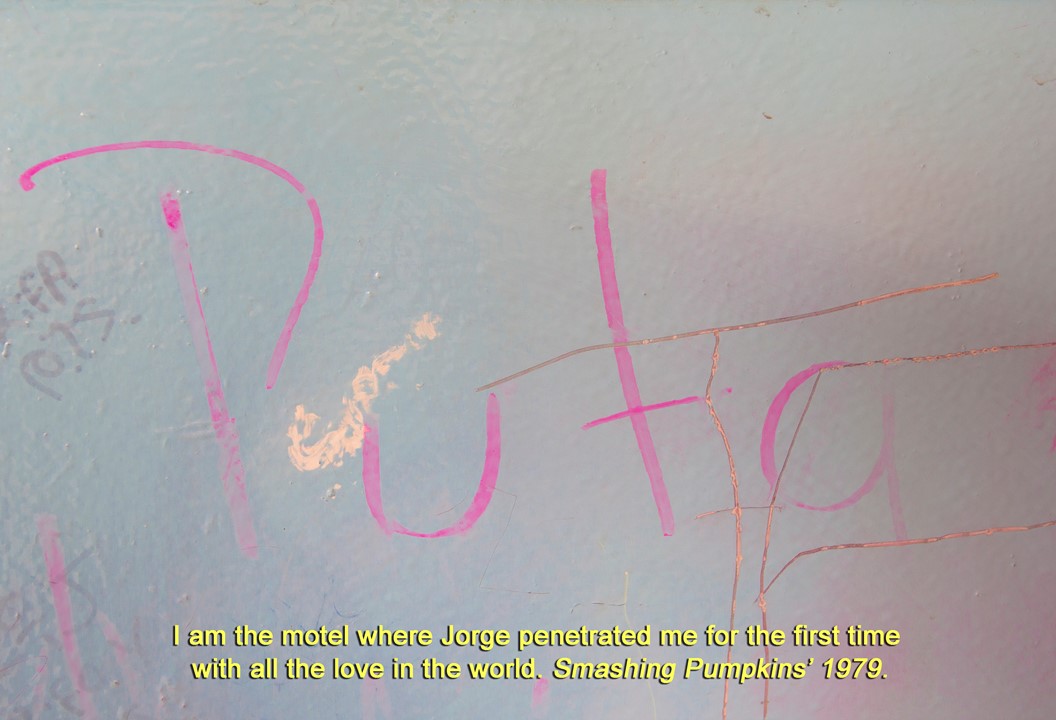

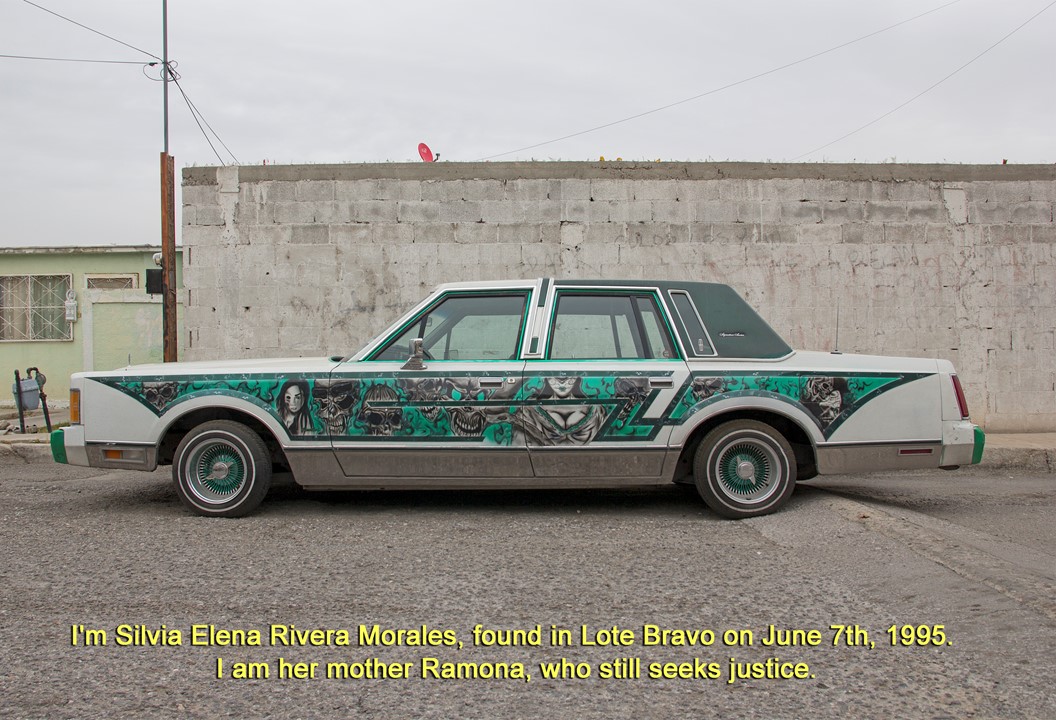

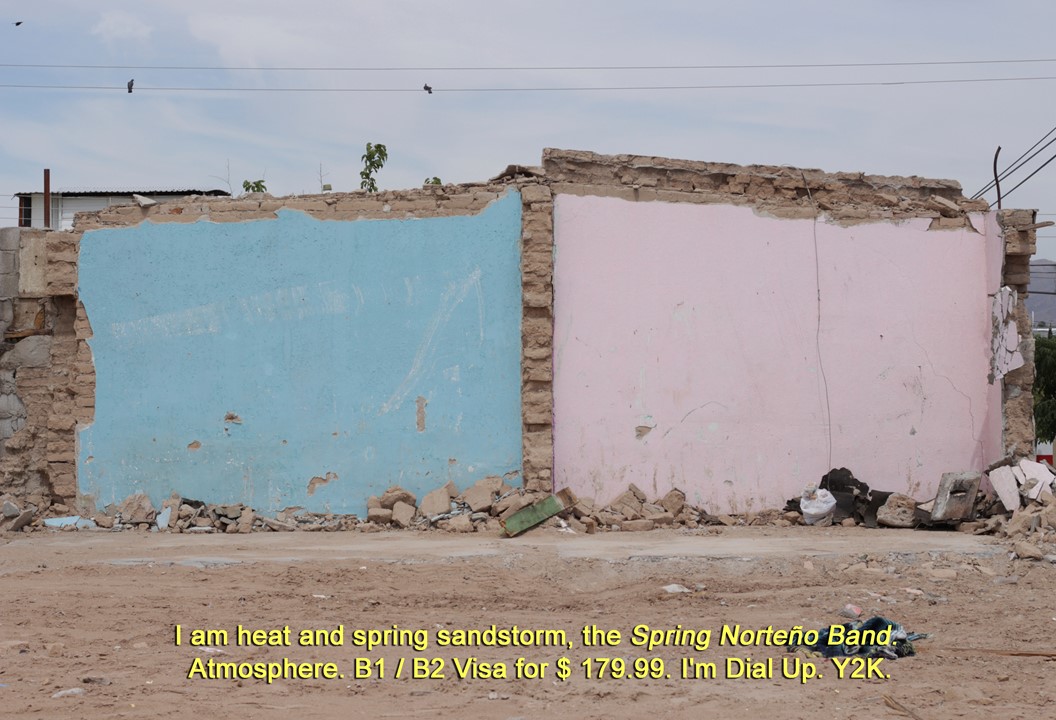

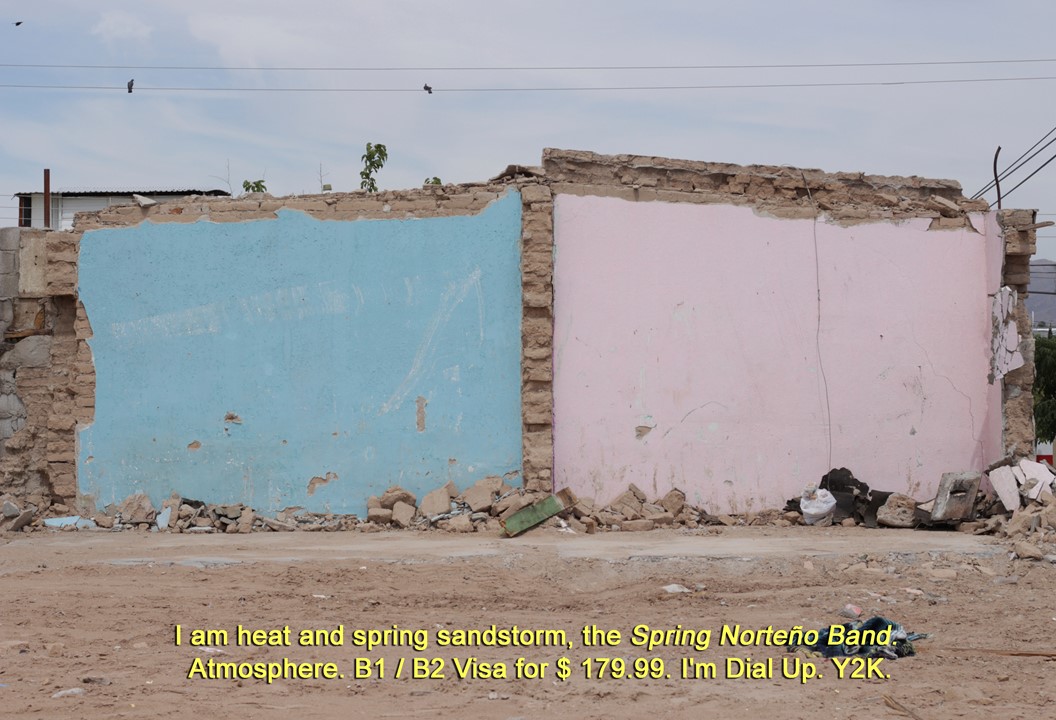

Why have you incorporated texts to your photographs?

If you are referring to Autorretrato Premonitorio, it is because it was a result of an experiment that searched alternate forms of representing the experience of being a woman and growing in Ciudad Juárez during the 90s, without resorting to the representation of the body. I did it during the Seminar of the Image Center in Mexico City in 2017. I believe that our tutor Veronica Gerber was of great influence. During the seminar, we reflected upon the weight of the text in the image, the images it can produce.

However, I also think it came from the cinema, the VHS format and the still image internet phenomenon.

Drawing from that experiment, I can conclude that identity is also constructed from the images that we observe from the world and that our territory has a major role in who we are. So, I take the landscape as a means for representing my body. I transformed my own memories and those of popular culture and cinema into text/words. To that, I may add another idea; my perception was altered by the violence that I experienced in my personal life and the context I lived in. “La violencia anula el tiempo”, says Elena Garro. These stills that resemble a movie are an attempt to allude to that idea.

What do you feel or think about when taking a photo?

Nowadays, I try to resist the consciousness that I have acquired with images. I try not to think too much, to take on an intuitive process and let myself feel attracted without a greater explanation on the space, landscapes and people that I portray. I believe that playing with other tools that are not necessarily a DSLR camera, allows me to get to my images through a different path. I play with different techniques such as drifting, the feeling of extraneousness that a thing might trigger and everything that I am constantly watching on the internet.

Elena: The territory in which you are living is particularly complex because it occurs as a hybrid on the US border and differs from Mexican-ness. Ciudad Juárez is part of an immediate notion of violence and drug trafficking; there is a part in your text where you talk about decolonization and it caught my attention. What are you referring to when you talk about the decolonization of the image? Which elements have allowed you to construct a visual/textual language that negates colonization in your territory?

Representation in art has historically been determined by western capitalist values, which are notions of beauty as white slim bodies. But also universality, individualism, progress, property, categorization and strict rational thinking. De-colonizing, for me, is to confront and question those values. The conversation about de-colonization is also about how these values influence our bodies, the places we inhabit and how we construct our identities. In the work of Carol Epíndola, this process is very clear. She questions the values of beauty in art where bodies like hers have never been represented. In her collages, she appropriates those symbolic spaces constructed in classical paintings. It is very subversive. It lets us see how the gaze constructs reality razing the question of who has the power to do it. Historically, white men and white societies from whom Carol proclaims that right. So de-colonization is also a matter of who is making the images. Like her, I position myself from a situated experience. This means that I talk about and through my own body, identity and territory.

There is also a longing for a previous state, the one before colonizers came. Therefore, a lot of work goes back to the original peoples. But in those practices, I think sometimes communities end up being tokens of the liberal artist or erased by the mestizo myth; as has happened to afro descendent communities in Mexico. It is common to see images of indigenous people and culture used in big museums, galleries and the tourism industry; while these same communities still live in harsh marginalized conditions all over Mexico. I believe that for those works to be transgressive art, people from these communities and backgrounds should have the opportunity to tell their own stories and represent themselves from their own situated experience. And we as artists of lighter skin or those from privileged backgrounds should work towards making the tools available to those communities.

Nonetheless, I consider there is an impossibility in the notion of de-colonization. Colonization did happen and it is very much linked to the way most societies understand the world. Border culture is an example of this. The border is a geopolitical construct where complex dynamics happen. So, it is hard for us to define ourselves into closed categories; either Mexican or American since our cities are made up of working-class people from all over the world. In my latest project, La Grieta at the edge of the world, I propose that our identity is in constant tension between the ideals that both the United States and centralized Mexico force upon us. In the paradigm of western culture, things are classified in order to be defined and later owned and controlled. Border culture and identities escape colonization values because paradoxically, they lack clear limits. The same happens in the notions of body and gender. So, my reflections about de-colonizing are situated in that intersection between language, representation, territory, gender and identity.

©Alejandra Aragón

Elena: You talk about decolonization and you also introduce gender and territory, you dismantle discourses of a convulsive present time; here, now. That is why I want to talk about the word transfeminist. What are you referring to when you mention this word, transfeminism?

I understand transfeminism as a space of intersectionality, where everything that crosses us, not just the condition of being a woman, raises questions about the framework that categorizes our condition and the construction of our identities. I think it’s a complex issue, and right now it’s a sticking point in feminist discussions. For some groups, it is difficult to understand that. For example; a poor peasant man, sexist as he may be, has many more disadvantages than a second-generation Mexican American woman with a light complexion who went to college. Or that a transgender woman, whose life expectancy is 35 years, given the deadly violence that threatens her life, is much more vulnerable than a cisgender woman.

Identity politics is a double-edged sword. It is true that we want to abolish categories yet, many times those stances enclose us in them. At the moment, identity politics are useful to us because they help us position ourselves in a world that makes us invisible and violates us.

ESPAÑOL

Esta entrevista se hizo con la amable ayuda de Elena Gálvez Mancilla. Historiadora y socióloga mexicana, estudiosa de la Amazonia y la historia indígena, interesada por la imagen como fuente histórica, amante de la fotografía y activista ecologista.

Cuando estaba en el proceso de selección para esta semana Latinoamericana, pensé en la diversidad del continente, quería it de punta a punta. Para la primera publicación, he elegido a Alejandra Aragón; Méxicana, de Ciudad Juárez. Esta ciudad ha sido referente del desarrollo de proyectos sobre transformación social, violencia y migración para muchos artistas; entre ellxs, Teresa Margolles.

Juárez es una ciduad fronteriza, la identidad está forjada por fuerzas y contextos varios. Aragón analiza su ubicación; explora las violencias íntimas y públicas y sus consecuencias en la psicología de la población. Existe cierta sutileza en su trabajo fotográfico, transita la representación con balance; no crea morbo ni espectáculo, pero tampoco esconde los problemas. Su obra crea más preguntas que respuestas y estimula la transgreción de la comunicación textual y visual.

©Alejandra Aragón

Alejandra Aragón es de Ciudad Juárez, México y es Licenciada en Artes Visuales por la Universidad Autónoma de Ciudad Juárez (UACJ). Formó parte del Seminario de Producción Fotográfica del Centro de Imagen en la Ciudad de México en 2017. Desde 2013 ha participado en diversas exposiciones colectivas en México, Sudamerica, Canadá y Europa. Su documental Las Noches invisibles formó parte del programa “Coordenadas” del Festival de Cine Ambulante en 2018. Recibió la beca de artes mexicanas (FONCA) en 2019. Es parte de Joop Swart Masterclass 2020.

A través de un proceso multidisciplinario utilizando video, audio, fotografía e imágenes encontradas, su trabajo explora cómo el territorio determina la experiencia e identidades de las regiones fronterizas a partir de una postura decolonial transfeminista.

¿Cómo empezaste a hacer fotografía?

Empecé cuando tenía 21 o 22 años. En Ciudad de Juárez la única fuente de trabajo es la industria de manufactura. Yo vengo de un entorno precario y mi único objetivo en la vida era ganar dinero y ayudar a mi mamá. Entonces trabajé en una fábrica hasta los 27 años. Sin embargo, cuando comencé un taller de cine, me di cuenta de que quería dedicarme al arte. En un inicio yo quería hacer películas, pero cuando un amigo me regaló una cámara SLR, la fotografía fija se convirtió en un camino más accesible para practicar conceptos básicos como la composición, la luz y las habilidades técnicas. Hice fotografía como aficionada durante años. De hecho, La Guerra se formó revisando el archivo que acumulé en esa primera etapa de mi carrera.

©Alejandra Aragón

¿Quiénes son los artistas que más influencia han tenido en tu trabajo?

He tenido influencias literarias. En La Guerra me refiero al trabajo de Arminé Arjona, poeta de Ciudad Juárez. Autorretrato Premonitorio está basado en un fragmento de El amante de Marguerite Duras. Me gusta la intertextualidad. La producción artística es una recopilación de todos los elementos e imágenes que hemos absorbido del mundo. De Elena Garro surge la noción de que “la violencia detiene el tiempo” y Cristina Rivera Garza proporciona elementos para hablar sobre la escritura del cuerpo. Respecto a la fotografía, siempre me atrajo mucho el trabajo de Melba Arellano, admiro como retrata a sus sujetos y lo que logra con la paleta de colores monocromática. Las grandes clásicas también, Maya Goded, Graciela Iturbide, Tina Modotti, Lourdes Grobet. Hay que tener en cuenta que hace solo diez años, antes de redes sociales como Instagram, el acceso y la visibilidad del trabajo de las mujeres eran muy limitados. En un inicio yo aprendí en libros, revistas y las pocas oportunidades que tuve para visitar exposiciones.

¿Cómo se desarrolla tu proceso creativo?

El proceso artístico se desarrolla a partir de las intuiciones e intereses de cada artista. Para mí, el aspecto más importante es mi experiencia situada; acercarme al arte desde la condición de mi cuerpo e identidad. Luego viene la importancia de la investigación con el fin de encontrar las mejores estrategias para abordar temas particulares de interés. Cuando trabajé en La Guerra, que es una recopilación de mis primeros trabajos realizados entre 2008 y 2013, lo hice a través de la revisión de mi propio archivo. No era consciente del valor de mis imágenes hasta que aprendí el valor del archivo y la naturaleza ingenua e intuitiva con la que pude documentar un evento tan extraordinario de una manera muy personal. Comencé a notar patrones, cómo el interior se conectaba con el exterior, conduciendo hacia la relación entre lo íntimo y lo público, retratando diferentes modos de violencia. Este proceso me ayudó a aceptar mi propia experiencia de esos tiempos violentos y su efecto en mi salud mental. Me permitió comprender mejor las profundas repercusiones que esta guerra ha tenido en la población de México. Es evidente, vivimos bajo un estrés postraumático, un estado depresivo sumergido en adicciones. Tuve un despertar político durante ese tiempo, pero fue solo después de muchos años que pude ver mis fotos desde una perspectiva diferente. La naturaleza del proyecto y el proceso también le dieron su forma de dípticos.

Las fotografías de Vine a La Pinta… me parecen especialmente interesantes por su coloración. ¿Nos puedes comentar un poco más sobre su proceso?

Todo lo que adquiere un tono rosa o magenta es el resultado de un negativo con sensibilidad al espectro de luz infrarroja. Por lo tanto, todo lo que es verde refleja el espectro infrarrojo. Para el proyecto Vine a la Pinta… decidí dar sentido, deliberadamente, a los colores generados por esta película, usarlos como una metáfora que revela un espectro invisible de la realidad. En este caso, las estructuras binarias de género. Es como ver lo que no podemos ver. Lo que se esconde en el trasfondo de distintos constructos de masculinidades hegemónicas como las construidas desde la cultura de mi propia familia mexicana, de los padres ausentes, el paternalismo del estado cuyas decisiones desplazaron a comunidades enteras. En ese orden, estas estructuras también están en la base del fenómeno del narcotráfico. Es hoy en día una forma más en la que los hombres, especialmente los jóvenes, precarizados, racializados, afirman sus poderes para alcanzar los ideales hegemónicos de la masculinidad.

Actualmente estoy trabajando en un libro de fotos sobre este proyecto, que también se presentará en una exposición el próximo año en el Rubin Center for Visual Arts en el otro lado, en Texas.

©Alejandra Aragón

©Alejandra Aragón

¿Cómo se representa la violencia?

Creo que estamos en un momento extraño con respecto a la representación de la violencia, consecuencia de las reflexiones de los últimos 10 años por fenómenos como la guerra contra el narco y la circulación de imágenes en internet.

Por un lado están las imágenes atroces espectaculares que buscan el morbo para el consumo. Por el otro están los ejercicios que estetizan, que terminan generando un efecto casi de ocultamiento, borramiento o despolitización de las violencias que intentan representar. Esto último es consecuencia de la crítica a la primera cuestión.

No sé cuál es la mejor manera de representar la violencia. A mí personalmente me gustó mucho lo que logró Tatiana Huezo en La Tempestad. Hace uso de recursos particulares: centrarse en el testimonio, usar el paisaje y metáforas, evitar mostrar a las víctimas para no re-victimizar sus cuerpos. Todo desde mucha empatía y cuidado. Son sólo algunos que logro identificar para lograr ese punto equilibrado donde no se reproduce violencia ni se estetiza.

Y pues la verdad no tengo mejor respuesta, no lo sé, yo también intento descubrirlo.

¿Cómo afectan los movimientos migratorios a tu trabajo fotográfico?

Existen temas paradigmáticos asociados a las fronteras. La migración es uno de ellos. Por lo tanto, no soy ajena a él. Yo parto, en la mayoría de los casos de mi experiencia situada, así que es desde ahí que trato de abordar la migración y hacer una distinción del desplazamiento, que son distintas.

En Ciudad Juárez todxs somos migrantes. Todo mundo viene de otro lugar, o solo está de paso. Ya sea recientemente o 30 años atrás. Así que para mí esa condición es la que siento que puedo abordar. Creo que hay tantas formas de migración como cuerpos atravesando el territorio.

Vine a La Pinta… es una de esas formas. Aborde el tema desde lo histórico, desde la memoria de una familia como la mía que nunca ha dejado de migrar. Porque creo importante que distingamos dos cosas: por un lado, que somos una especie errante, migramos, de ahí lo absurdo de los límites geopolíticos. Pero por otro, que en la historia actual lo que llamamos migración es desplazamiento forzado, resultado de la precarización neoliberal.

Otras veces hago cosas más breves, respondiendo a la urgencia de un tema. El año pasado hice un reportaje para apoyar la recaudación de fondos de la casa de migrantes LGBTTTIQ, mujeres y niñxs Respetrrans. Son los grupos más vulnerables del tan extraordinario fenómeno de migración que vimos suceder con las caravanas de cubanxs, sur y centroamericanas. Era necesario visibilizar el tema dada la urgencia del desplazamiento que ha tomado carácter de crisis humanitaria.

¿Por qué has incorporado textos a tus fotografías?

Si te refieres a Autorretrato Premonitorio es porque fue resultado de un experimento que buscaba formas alternativas de representar la experiencia de ser mujer y crecer en Ciudad Juárez durante los 90, sin recurrir a la representación del cuerpo. Lo hice durante el Seminario del Centro de Imagen en la Ciudad de México en 2017. Creo que nuestra tutora Verónica Gerber fue de gran influencia. Durante el seminario, reflexionamos sobre el peso del texto en la imagen, las otras imágenes que puede producir. Sin embargo, también creo que provino del cine, el formato VHS y el fenómeno del still en Internet.

A partir de ese experimento, puedo concluir que la identidad también se construye a partir de las imágenes que observamos desde el mundo y que nuestro territorio tiene un papel importante en quienes somos. Entonces, tomo el paisaje como elemento para representar mi cuerpo. Transformé mis propios recuerdos y los de la cultura popular y el cine en texto/palabras. A eso, puedo agregar otra idea; como mi percepción fue alterada por la violencia que experimenté en mi vida personal y el contexto en el que viví. “La violencia anula el tiempo”, dice Elena Garro. Estas imágenes fijas que se asemejan a una película son un intento de aludir a esa idea.

¿Qué sientes o piensas cuando tomas una foto?

Actualmente trato de luchar contra la conciencia que he adquirido sobre las imágenes. Así que trato de no pensar mucho, de asumir un proceso intuitivo dejarme atraer sin mayor explicación a los espacios, los paisajes, o las personas que siento necesidad de fotografiar. Además, creo que el jugar con otras herramientas que no sea sólo la cámara de DSLR permiten llegar a las imágenes de otras maneras. Así que hago juegos entre las técnicas, las derivas, el sentimiento de extrañeza que me generan las cosas, y todo lo que observo constantemente en internet.

Elena: Particularmente, el territorio en el que estás, es sumamente complejo porque sucede en una hibridación de frontera con Estados Unidos que dista mucho de la Mexicanidad. Ciudad Juárez es parte de un imaginario inmediato de violencia, de narcotráfico; me llamó la atención que en una parte de tu texto, hablas de la descolonización. ¿A qué te refieres con la descolonización de la imagen? ¿Qué elementos te permiten construir un lenguaje visual/textual que refuta la colonización de tu territorio?

La representación en el arte ha estado históricamente determinada por los valores capitalistas occidentales, que son nociones de belleza de cuerpos blancos y delgados. Pero también universalidad, individualismo, progreso, propiedad, categorización y pensamiento racional estricto. Descolonizar, para mí, es confrontar y cuestionar esos valores. La conversación sobre la descolonización también trata sobre cómo estos valores influyen en nuestros cuerpos, los lugares que habitamos y cómo construimos nuestras identidades. En la obra de Carol Epíndola, este proceso es muy claro. Cuestiona los valores de la belleza en el arte donde nunca se han representado cuerpos como el de ella. En sus collages se apropia de esos espacios simbólicos construidos en la pintura clásica. Es muy subversivo. Nos deja ver cómo la mirada construye la realidad arrasando con la cuestión de quién tiene el poder para hacerlo. Históricamente han sido hombres blancos y sociedades blancas de quienes Carol proclama ese derecho. Entonces, la descolonización también es una cuestión de quién está haciendo las imágenes. Como ella, me posiciono desde una experiencia situada. Esto significa que hablo de y a través de mi propio cuerpo, identidad y territorio.

También noto que hay un anhelo por un estado anterior al de la llegada de los colonizadores. Por lo tanto, mucho trabajo aborda a los pueblos originarios. Pero en esas prácticas, creo que a veces las comunidades terminan siendo instrumento del artista liberal o borradas por el mito mestizo; como ha sucedido con las comunidades afrodescendientes en México. Es común ver imágenes de culturas indígenas utilizadas en grandes museos, galerías y la industria turística; mientras que estas mismas comunidades aún viven en duras condiciones de marginación en todo México. Creo que para que esas obras sean arte transgresor, las personas de estas comunidades y orígenes deberían tener la oportunidad de contar sus propias historias y representarse a sí mismas desde su propia experiencia. Y nosotros, como artistas de piel más clara o de origen privilegiado, deberíamos trabajar para ofrecerles las herramientas que necesiten esas comunidades para que su propia voz se escuche.

Sin embargo, considero que existe una imposibilidad en la noción de descolonización. La colonización ocurrió y ha determinado la forma en que la mayoría de las sociedades entienden el mundo. Las culturas fronterizas son un ejemplo de esto. La frontera es un constructo geopolítico donde ocurren dinámicas complejas. Entonces, es difícil para nosotros definirnos en categorías cerradas; ya sea mexicano o estadounidense ya que nuestras ciudades están formadas por gente de clase trabajadora de todo el mundo. En mi último proyecto La Grieta al borde del mundo propongo que nuestra identidad está en constante tensión entre los ideales que tanto Estados Unidos como el México centralizado nos imponen. En el paradigma de la cultura occidental, las cosas se clasifican para ser definidas, luego controladas y finalmente poseídas. La cultura y las identidades fronterizas escapan a los valores de la colonización porque, paradójicamente, carecen de límites claros. Lo mismo ocurre con las nociones de sexo, cuerpo y género. Entonces, mis reflexiones sobre la descolonización se sitúan desde esta intersección entre lenguaje, representación, territorio, género e identidad.

©Alejandra Aragón

Elena: Hablas del sentido de la decolonialidad en la que incorporas elementos de género, del espacio y desmontas discursos de un presente que se convulsiona, de aquí y ahora. Por ello quiero preguntarte por la palabra transfeminista. ¿A qué te refieres con esa palabra, transfeminismo?

El transfeminismo lo asumo como un espacio de interseccionalidad, donde todo aquello que nos atraviesa, no solo la condición de ser mujer, genera preguntas sobre el marco que categoriza nuestra condición y la construcción de nuestras identidades. Creo que es un tema complejo, y en este momento es un punto de fricción en las discusiones feministas. Para algunos grupos es difícil entender que, por ejemplo: un hombre pobre campesino siendo tan sexista como pueda ser, trae consigo muchas más desventajas que una mujer mexicoamericana de segunda generación de tez clara que fue a la universidad. O que una mujer transgénero, cuya expectativa de vida es de 35 años dadas las violencias mortales que las atraviesan, es mucho más vulnerable que una mujer cisgénero.

La política de identidad es una espada de doble filo. Es verdad que queremos abolir las categorías y muchas veces esa política nos encierra en ellas, pero en este momento las políticas identitarias nos son útiles porque nos ayudan a posicionarnos en un mundo que nos invisibiliza y nos violenta.

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

The International Women in Photo Association Awards: Rayito Flores Pelcastre: Chirping of CricketsMarch 14th, 2024

-

Mexican Week: Cannon BernáldezFebruary 6th, 2024

-

Semana Mexicana: Felipe “Chito” TenorioFebruary 5th, 2024

-

Photographers on Photographers: Barry Schwartz in Conversation with Victor MoriyamaJune 29th, 2023

-

Photography Into Sculpture: Lou PeraltaJune 12th, 2023