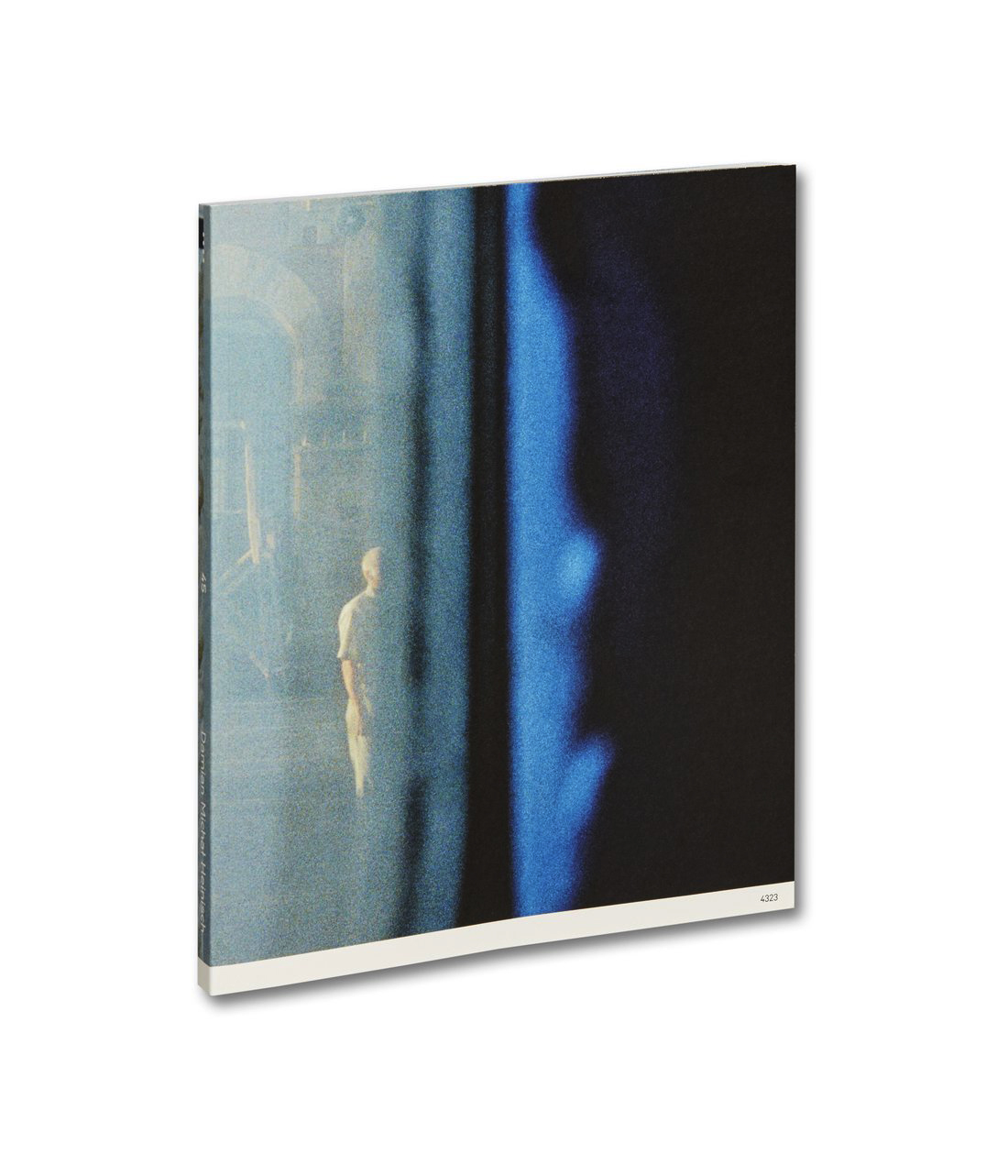

Focus on Norway: Damian Heinisch: 45

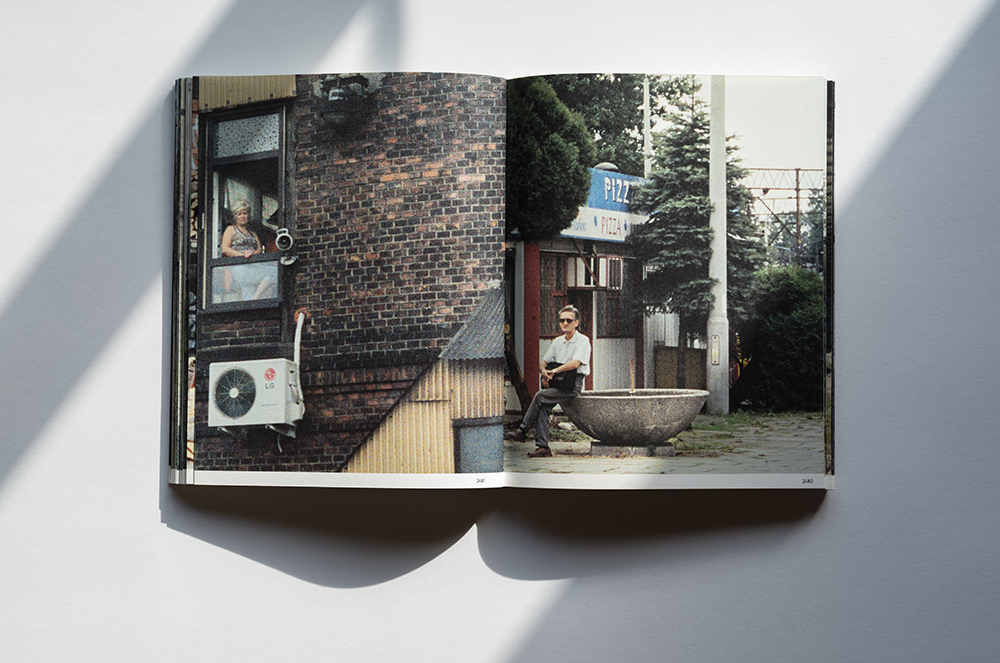

As I delved into the multi-faceted world of Damian Heinisch’s visual memoir, diary, reportage, history, travelogue and evocations through time and space, I was struck by the timeliness and timelessness of his vision. Ironically, his recent book and project, “45”, struck a deep chord in me as my own family history and his, through four European countries, share some common, though disparate, threads…in other words, his images struck home. He weaves a tapestry of family and European history by following a trail inspired by the last written words of his ill-fated grandfather that ties in with his own search for a personal “heimat”. The journey may be a re-creation, but it mirrors the complicated consequences of acts of history that become so very personal and transformative. Share in the journey that Damian creates, and you may possibly unearth threads of your own family’s tapestry.

Damian Heinisch is an Oslo-based photographer with a MA in Visual Arts from the Folkwang School in Essen, Germany. After spending his childhood in Poland and attending school in Germany, he moved to Norway in 2001. For over 30 years, his work has focused on landscapes, architecture and space in general. While Heinisch began by taking a traditional approach to his practice, recently his work has evolved into a narrative confronting themes of identity and immigration. More and more, he finds himself exploring this subject through the lens of historical consciousness and emphasizing the human soul. Heinisch’s work has received national and international awards and has been exhibited in museums, institutions and galleries around the world. Since 2003, he has been part of the permanent teaching staff at several institutions, sharing his experiences with students and participating in numerous workshops. He is the recent winner of the “First Book Award” by Mack for his book “45”. Heinisch also serves as a Leica ambassador in Norway.

“45”

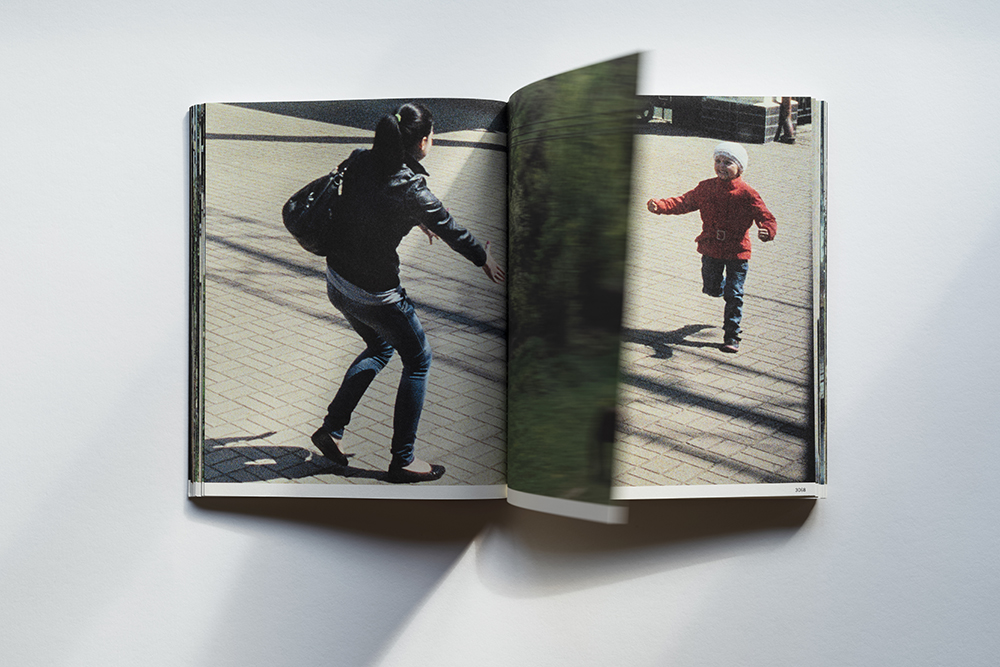

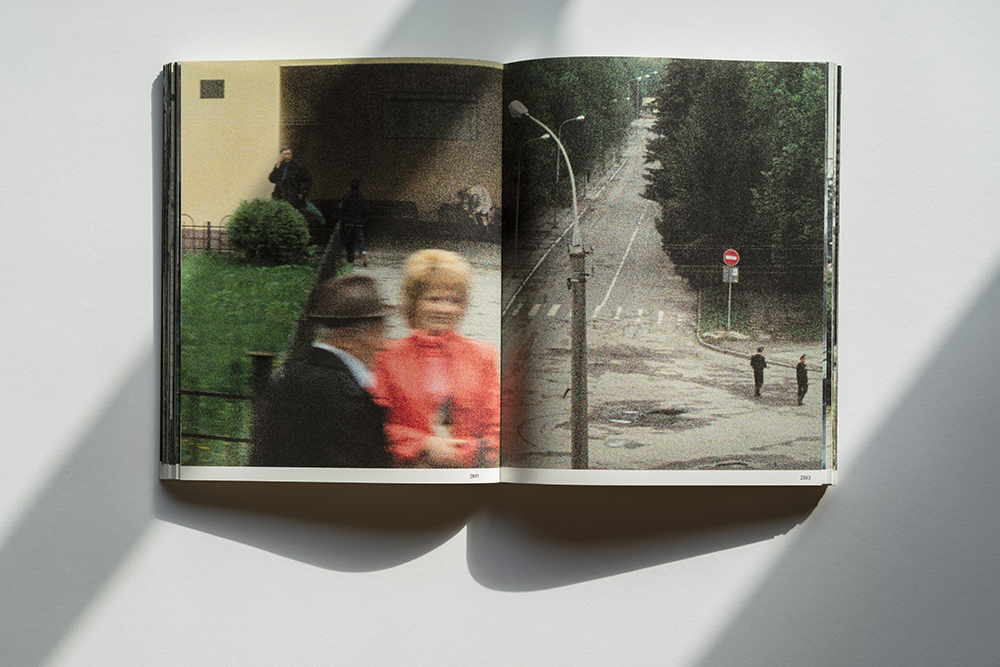

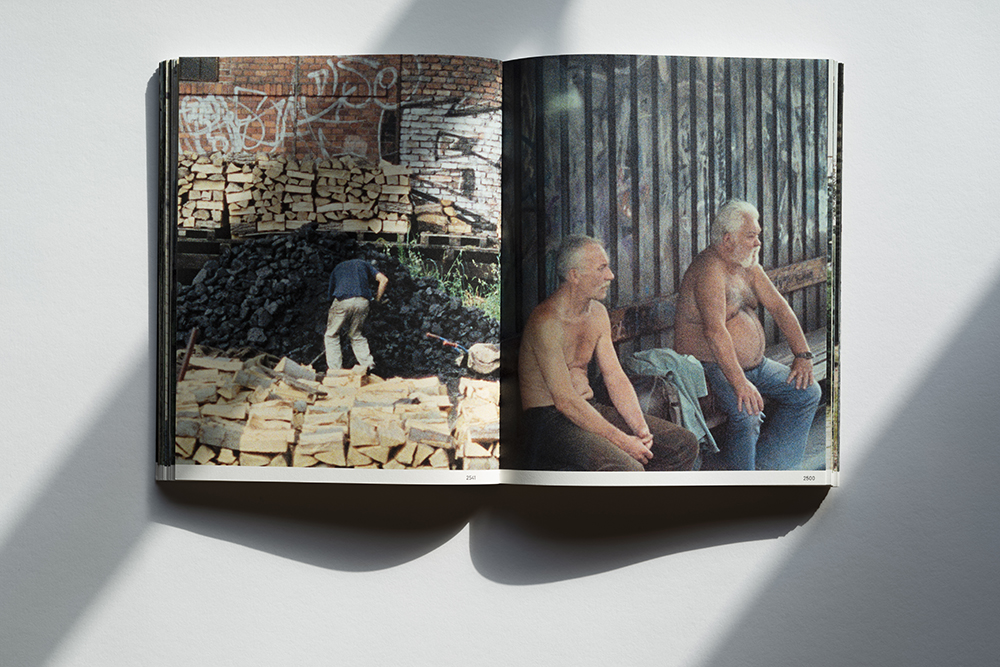

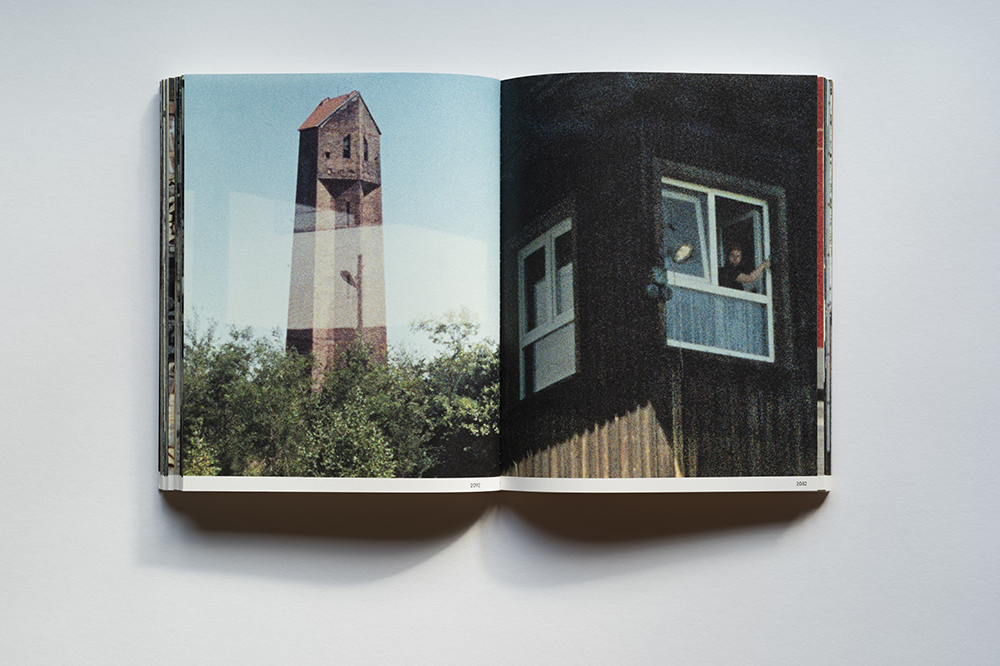

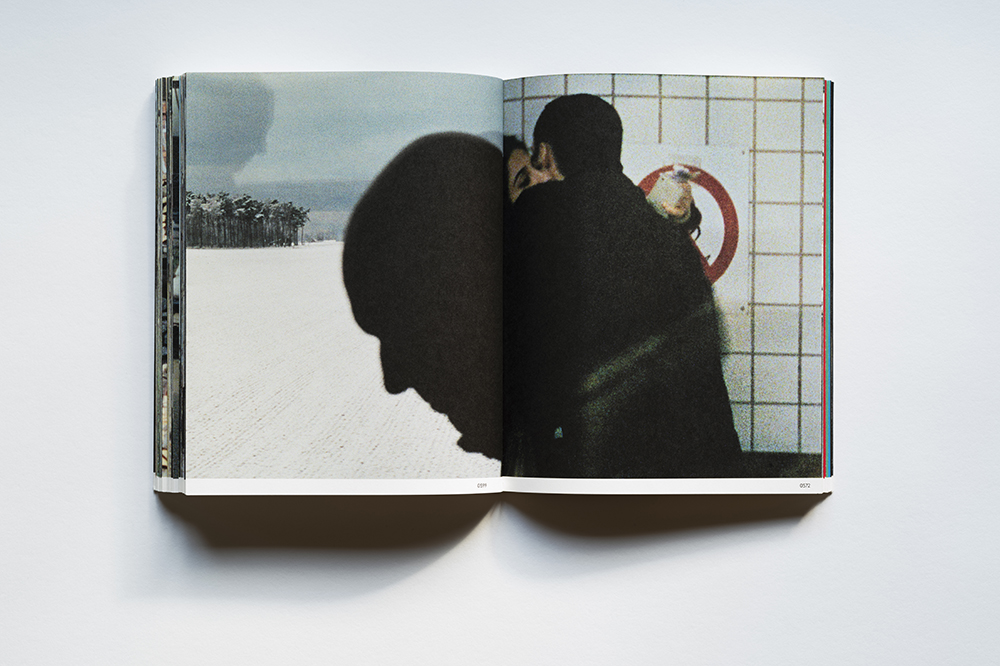

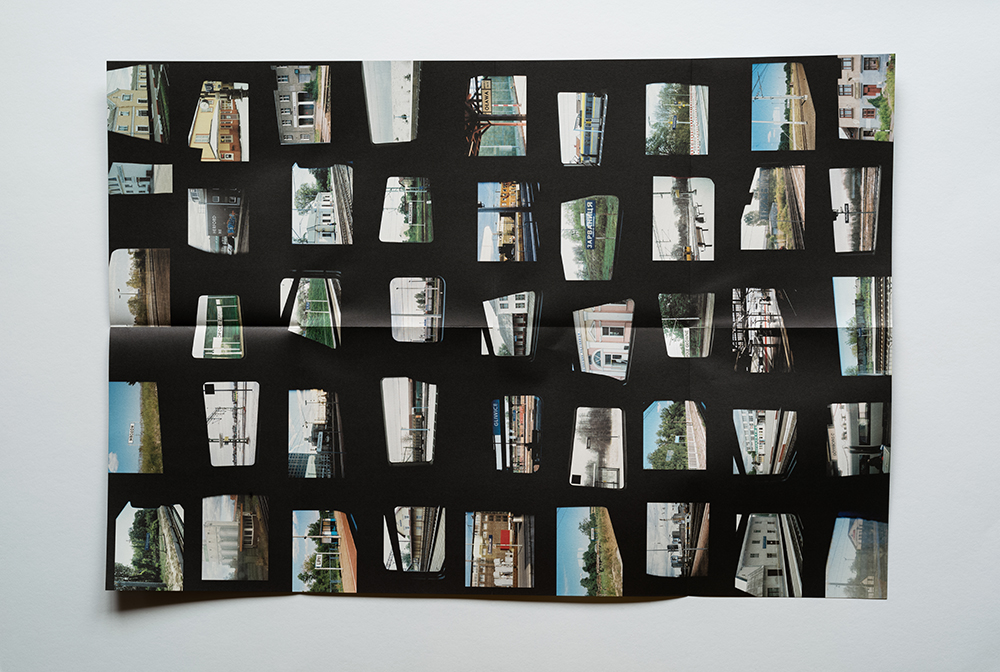

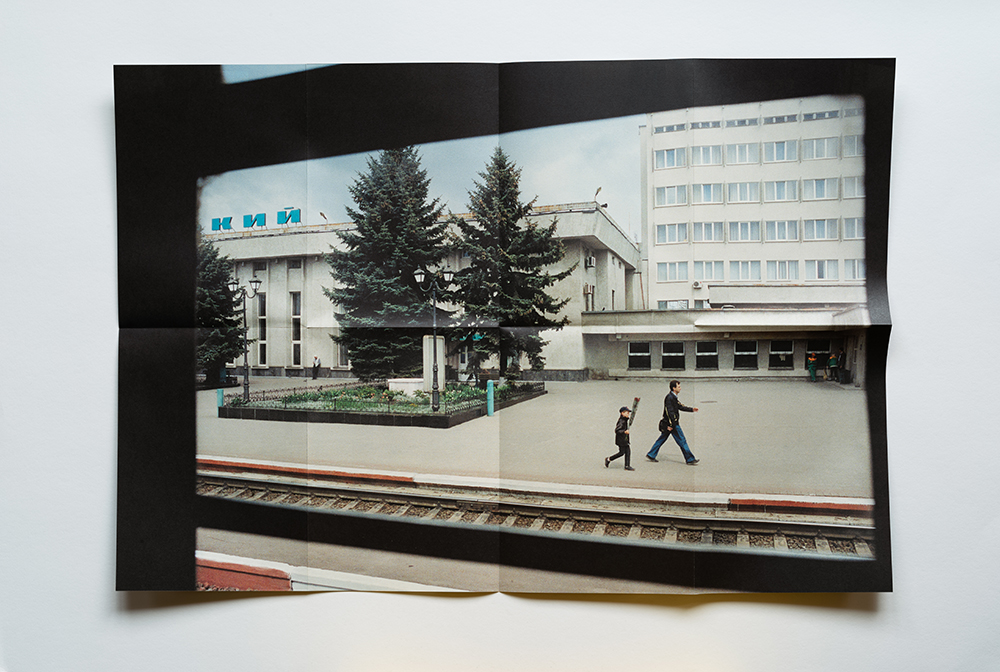

Working on a long-term project focused on my family’s history in the context of the Second World War, it became inevitable that I would visit my grandfather’s unknown grave in Ukraine. Back in 1945, he disappeared like a ghost along with countless men from Upper Silesia. I understood that my family’s lives had been considerably influenced by forced immigration and that, as a method of transportation, trains had played a significant role in the process of resettlement. I began to respect the “forced” journeys of my family members while at the same time documenting my own. The train window became the stage. In the end, I embarked on three journeys: first the physical journey, holding my 35mm camera to my eye for hours on end.

The original film material became part of an installation based on slide projection, allowing me to approach the book in a different way. This led to the second journey into my developed films, where I started to extract human presence in their respective physical surroundings, confronting my findings and contrasting them on the page. The sequence is strictly dictated by the chronology of the journey.

The final journey led me into the virtual world, mapping the train tracks kilometre by kilometre on Google Maps all the way from Oslo to Debalzewo in Ukraine. As the trigger for this cathartic journey, Ukraine felt like the natural place to start the book. Texts based on the journeys of each family member complement the image sequence and help solve the puzzle. At this point in their journey, each family member turned 45.

The book’s narrative challenges the issue of forced immigration, which has influenced the lives of countless families in Europe and continues to do so today. Eight months after I returned frommy journey, a new conflict erupted in the Donetsk region, leading to an ongoing war.

First of all, congratulations on “45” being selected for the “First Book Award” by the publisher, Mack. In reviewing your work, I noticed your acknowledgement that you have evolved from the more traditional aspects of landscape, architecture and space into a narrative approach confronting specific themes. What prompted this transition after so many years?

Thank you very much, Michael. It still feels surreal to me that “45” was awarded the prize. Given that my first book journey took a long time and was utterly challenging on occasion, I am honored and proud of the recognition.

Photography has followed me since childhood, and I took my first serious steps into the adventure when I was 15. I see a clear parallel between my development as an individual and as a visual person. The medium follows the evolution of your life.

I was born into a working-class family at the time of the Cold War in one of the most polluted areas in Eastern Europe. My family lived in a five-story building in a neighborhood encompassing coalmines, powerplants, churches and cemeteries. On some days it seemed you could literally cut the air – with a yellowish stinky veil emanating from tall industrial smokestacks.

This combination felt quite existential and insane. Perhaps, it is the reason why I have developed a longing for a pure and untouched landscape, similar to the imaginations of the great American West Coast Photographers. From an early age the miraculous visual world of Brett Weston struck me deep in my soul and my obsession with the medium was sealed. What I saw there was a fascinating abstract, dark and expressive abyss and it appealed to me instantly.

Before attending the Folkwang School in Essen, I set out on a three-month adventure to Scotland, Ireland and Wales in 1990. It was a trip where I could project my longings onto the rough landscape of the northern hemisphere. This harmonic and innocent experience was sadly interrupted by the death of my mother shortly after my return. What followed, was a journey into a very personal landscape driven by sorrow, but also hope, with photography as my trusted companion.

While studying in Essen, a transformation took place from a classical to an intensely personal perception of the landscape theme. The city, itself, was a very limiting place for inspiration which led to my solution in creating constructed landscapes. After many years I confronted the landscape within me and escaped to the mountain world of the Alps as a solution. The result was my creation of a semi-documentary short film called PYLOD.

With its intimate style and expressive sound, the film depicts the machine’s parallel existence, its relentless rhythm and will of its own, taking the viewer into a mechanical world of poetic, repetitive and romantic imagery. An encounter with the machine as a seductive organism is also a meeting with the darker reasoning of the human mind. Feelings of restlessness, longing, loss, impotence and loneliness intrude into the images of a powerful and frozen mountain realm. I discovered and extracted the imagery of my childhood and projected it on the mountain landscape.

The last chapter and the latest transition in my creative process happened in becoming a teacher and in having an epiphany. It was triggered by a period in my life when I needed to make critical decisions that were intense and personal. I suddenly saw myself as an observer of my own life while simultaneously internalizing the meaning of photography. This revelatory period led to a new approach embracing the theme of a new landscape narrative involving the human soul. I am at the stage in life that forces you back to your roots in order to understand your own identity.

Besides, I had no choice. I inherited a diary written by my grandfather during the period of his deportation from Ukraine to his ultimate death in an unmarked grave. The diary was written in sorrow and despair. It was so impressive to view with letters only 2 mm high and as dense as possible to save paper. He wrote in this diary every single day during his deportation which ended after ten months on October 5, 1945. No one knows where his grave is.

This little diary had been untouched for many years on my shelf. My father gave it to me, but I never dared to open it. I was not ready to face its implications. Eventually I returned it to my father without having read one sentence. A few years ago I asked for it again, and read the whole book this time. It was like opening Pandora’s box and it changed my life completely. I was forced to change, and I understood that it was time to react, as an artist.

Your project, “45” deals with a family narrative that crosses many international borders and your own journey in life mirrors that narrative. How has your family history influenced who you are as photographer?

I mentioned earlier that photography has intrigued me since my childhood. I remember my father being a passionate amateur owning a darkroom in the flat where he grew up. It was located in the town of Gliwice, Poland, where my family resided when World War II began and where heavy artillery battles in the streets took place six years later between the Red Army and the German Wehrmacht.

The following period was shaped by hunger and despair as my family lost almost everything while the nation and culture underwent a massive transformation under the Communist regime. I grew up in a kind of holding situation at home with a father who couldn´t accept Poland as his home anymore. Someone who longed to leave for a new country and who got punished for his longings by the political system. Fired from his job and not being able to provide for his family, he found a solution by earning some money through wedding photography.

I remember sitting on his lap while he was holding his camera in his hands allowing me to look through it. I was never allowed to hold it myself – too dangerous and too precious. But it was my father who placed my first camera into my hands, a Polish double lens camera called “Start.” I remember being with him on several occasions in our old family flat but was never allowed to enter alone into the small room that was his studio. One day my curiosity got the best of me and I dared to take a look. It was a fascinating room with many shelves, boxes, tanks for developing the films and an enlarger. As I left, I closed the door but left the key in the lock inside. My father got very angry and I had to crawl through a small window from the balcony into the studio to open the door again. This was perhaps the metaphor for my first steps into the world of photography.

You carry these images and your family’s history deep within you always. Being forced to an awakening lately it became obvious, that these happenings needed to be faced. For many years I was not able to read and gain information through this vital medium of literature. Something miraculous happened and it felt like a door opened within me allowing the entrance to a hidden rom. Photography helped me being able to reflect on history in general and understanding the complexity of Europe’s history a bit more.

Living all these years with photography gave me a much deeper insight in understanding its hidden connotations. Without doubt I have changed as a photographer, but I couldn´t say it was necessarily for the better. In the end I am definitely more experienced, but far more importantly I hope it made me a better human being ☺.

I am fascinated by the fact that you photographed the entire project of “45” through the windows of trains through Ukraine, Poland, Germany and Norway. What prompted you to use that precise technique? Were there any unusual experiences that you encountered while riding the rails?

At the time I was working on a long-term project and I focused on my family’s history in the context of the Second World War. It became inevitable that I would visit the site of his grandfather’s unknown grave in Ukraine. I realized that my family’s history had been considerably influenced by forced immigration and that, as a method of transportation, trains had played a significant role in the process of resettlement. It therefore made sense to take the train to all these places to which they had travelled – Ukraine, Germany, Poland and Norway – and to document this journey.

The journey was not photographed in one go. Since my main project relates to the four seasons, I also decided to travel through the influence of time. I didn´t see the long train journey as a great achievement in itself and I remember being on trains several days on inter-rail journeys during summer holidays of my youth. It is easy to buy a ticket today and reserve a comfortable place. In this respect the physical project is rather a documentation and the concept it´s limitation. Ultimately, I did four journeys within a period of seven months in 2013. I always started at the point, where the previous journey ended. So, in the book you will find a ride through four seasons, starting in the spring in Debalzewo, Ukraine, and ending with a pale snow on the train platform in Oslo.

My self-imposed limitation of movement and the framing through the train window was a beautiful meditation. There was enormous energy and tension. I did every route of the journey just once and therefore there was just one chance to get it right. Most of the time I sat with the camera glued to my eyes. People around me became suspicious and curious, but eventually they got used to the constant clicking of my Leica. Trains move very fast and your reaction as a photographer must be instinctive. Many of the images I saw through the viewfinder I was not able to capture since I was too slow, and it pained me to miss a shot. Photography can be very serious as it is a projection of your inner longings. Images are stuck within us and want to be resolved by becoming part of a concrete, two-dimensional space, and that is photography for me. I was chained to the train window and that became my reality.

But it is not just the result of the physical journey that we see in the book. On the contrary, the viewer sees only a piece of the entire journey. There was also my creative journey into the 4324 chronological images that I developed, edited and sequenced into book spreads. A key example is the image of a boy and his father heading along a train platform to welcome their arriving mother/wife. This was a situation I could relate to very well from my memories. The third and final journey took me into the virtual world, where I followed the train tracks kilometer by kilometer all the way from Oslo back to Debalzewo in Eastern Ukraine.

I notice that when you are not actively pursuing your own photographic endeavors that you teach young Norwegian photographers at the Bilder Nordic School of Photography in Oslo. How would you define the Nordic style of photography? What trends do you observe as you teach the next generation of Norwegian photographers?

Teaching has always fascinated me as something I wanted to do from an early age. I have shared my knowledge on several occasions and was leading occasional workshops, but at the end of my 30’s I had the opportunity to teach regularly during an entire semester. I liked it very much and in no time twelve years have suddenly passed. I have taught each of the school´s offered courses and have also been involved in creating a part of the teaching curriculum, so I have become a kind of universal jack-of-all-trades.

We don´t do a Scandinavian style…it´s not like a sauna or a Volvo! At school we have a fantastic team that is quite international. It is a unique milieu and the reason, why I continued to teach all these years. The school is one of the largest schools of photography in Scandinavia, but maybe tiny compared to schools elsewhere. That gives us the ability to care more about each individual student’s needs. The staff consists of teachers who are highly motivated and practical, so we are not reduced to a theoretical framework.

But the span of education is limited to just a two-year program. We try to use those four semesters as effectively as we can. If the participant is focused and well-structured, the output can be enormous. I often see a total transformation of students during their tenure here. But in the end, it is clear, that our input just creates a base, which each individual needs to build upon after graduating.

I see and feel a lot of energy, curiosity, and engagement, but also despair and resistance. Understanding the motivation and the originality in the students’ projects is the highest goal for me. In that moment, something quite complex happens – I put everything I have seen and experienced in relation to the work that lies in front of me. I try to inspire and guide the students by challenging their ideas. Ultimately, I am glad not to see 50 copies of myself leaving our school. If I see someone stepping into my path, I view it with suspicion.

Providing a critique is always difficult because photography is so incredibly personal. One must find a good pedagogic approach, but also not hold back. I remember seeing students being crucified by instructors’ critiques during my own education…a totally harsh method that belongs to days passed.

Introducing the principles of story-telling through images may be the school’s highest goal and methodology. Students get involved in textual work learning to be able to express their ideas through narrative as well. We have teachers who have been editors at the highest institutions of photography as well as highly acclaimed international guests coming in regularly. The graduates finish their two years with a presentation of their work in an exhibition with a contemporary theme connected to values. The final day is always filled with a lot of joy and tears. Many strong friendships grow out of this intense period…a bond for life.

What projects do you have in mind for the future?

I have mentioned previously that “45” can be seen in a wider context. A prologue to a long-term project, which I have been working on for the past ten years. It is the red line on a journey through current day Europe stopping along 4 places connected to my family history concerning the theme of immigration and loss. I am fortunate in having a grant from the state that supports my efforts in developing this long term project.

This adventure took me from my home place in Oslo to Essen, Germany, Gliwice, Poland and finally to Donetsk, East Ukraine. The narrative is supported by a conceptual structure. Four European nations, four generations, the four seasons and the four elements form the basis of the narrative and symbolize the cycles of life. The four regions visited are further enhanced by four photographic approaches chosen for authenticity in relation to the events that took place in each. The historical timeline begins with my grandfather’s deportation and death in Ukraine back in 1945. After inheriting my grandfather´s diary, which he wrote every day during the period of his deportation, I decided to travel back to the Donbas region and visit his unmarked grave. The selected images attempt to capture traces and consequences of the genocides buried in the brutality of world history that continue to manifest themselves in today’s reality. In Silesia – where my grandfather, my father and I grew up – I documented memories of my childhood. We lived in an area brutally transformed by the events of WWII. Today, it is part of the European Union and remains home to half of my family. In Germany, I spent six years following my father’s everyday life in exile after he left for West Germany in 1978 and followed his dream of returning to a German-speaking culture. Norway is my exile, freely chosen, and allows me to reflect on issues of identity and affiliation no more than 500 meters from my front door. So, “45” is part of a long-term project, that ultimately will become four books, collected in a slipcase.

Immigration has affected millions of families throughout Europe, and its influence continues. Europe is an area characterized by a number of conflicts. Tragically, my trip to Ukraine was followed by a bloody civil war. The cycles of history seem to repeat. This project takes on a universal significance, raising questions about deportation, emigration and above all, about

the lost and our common heritage.

From now until January 29, 2021, you can visit an exhibition of “45” at the Webber Gallery in London.

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

The 2026 LOVE Exhibition, Part 2February 14th, 2026

-

The 2026 LOVE Exhibition, Part 3February 14th, 2026

-

The 2026 LOVE Exhibition, Part 4February 14th, 2026

-

The 2026 Lenscratch New Beginnings Exhibition (Part II)January 31st, 2026

-

South Korea Week: Sung Nam Hun: The Rustling Whispers of the WindJanuary 16th, 2026