Anna Beeke: Storytellers

When I was a child my family relocated from California to Connecticut. Leaving behind massive cathedrals of sequoias and redwoods for humbler stretches of red maple and birch. Despite the vast difference in scale, texture, and palate I have no memory of ever comparing the two places. The forest was the forest. A place of simultaneous refuge and peril. Where children live out their days as conquering knights or are swallowed up by portals in the wet crevices of craggy rocks. A lawless expanse where teenagers rollick drunkenly in the dark and the natural cycle, cruel and perfect, rolls on like an impenetrable wheel. These are the stories I tell myself about the forest. They contribute to a greater mythology more expansive than any swath of woodlands the world over. Today, we visit Sylvania, a “composite forest-land” created by Los Angeles based photographer and videographer Anna Beeke. In Beeke’s images we find the holy glow of the damp coniferous forests of the Pacific Northwest. While the human figure is sparsely seen in these arboreal depictions the presence of our species is felt throughout in the form of satellite dishes, tree tags, and stop lights. Despite the increasingly domestic nature of these wooded spaces Beeke’s images are endowed with a sense of magic and wild possibility, reminding us that even in this age of depleting mystery the known world is but an island. The unknown is greater than human mythos can conceive.

Anna Beeke is a documentary/fine art photographer and videographer based in Los Angeles. She has an MFA from the School of Visual Arts (2013), a certificate in photojournalism from the International School of Photography (2009), and a BA in English from Oberlin College (2007). Anna was chosen for PDN’s 30 in 2015, and among other honors has received the 2015 Wallis Annenberg Prize and the 2012 Humble Arts and WIP-LT/Lightside Materials Grant. Her first monograph, Sylvania was published by Daylight Books in 2015. Most recently, she worked as a videographer on the Netflix documentary series Unnatural Selection. Anna’s work has been exhibited across five continents and she is represented by Uprise Art.

Sylvania

Across cultures and centuries, the forest has occupied a unique place in our collective imagination. Light and dark, good and evil, chaos and peace: these oppositions are as fundamental to the forest’s liminal landscape as they are to the human experience.

There are countless histories and myths that involve humankind venturing beyond the structured limit of civilization into the chaotic labyrinth of the woods. Like so many before me, I too went into the woods in search of adventure, transcendence, and the unknown. I entered the forests of the Pacific Northwest because of some ineffable thing connected to memories and mythologies of my own, and continued my quest in other American woodlands seeking a more universal understanding of the varied and branching experience of humanity in relation to this primal, mysterious landscape.

While I doubt I will ever be fully out of the woods, for now I have returned from my arboreal outings with Sylvania, a composite forest-land of photographs comprising scenes from various and sundry American woodlands. Through images of both real and depicted nature, this book examines the differing characteristics of these woods while also seeking the Forest Universal rooted in them all, exploring the physical and metaphoric presence of the forest in the contemporary world.

Beyond the broader cultural imagination and mythos, the forest plays into our psyches based on lived experience. What was your relationship to the forest growing up? Was it a place you had access to?

Growing up in Washington DC and its suburbs, I had access to one of the great urban forest resources – Rock Creek Park – so the forest was always very much a part of my life from a young age. I was an equestrian and I would go on long trail rides alone with my horse through these woods at least once a week during middle and high school. It gave me an amazing sense of freedom and wonder, and let me decompress from the pressures of school and the drama of adolescence. I also spent many childhood summers living in cabins in the woods at sleep away camp in the mountains of West Virginia. And, of course, my imagination was steeped in the mythos of the forest from the very start through childhood literature and fairytales.

You mention in your statement that you were specifically drawn to the Pacific Northwest for ineffable reasons. What were your imaginings of the region prior to traveling there? What did you find?

I had always felt drawn to the Pacific Northwest for reasons I couldn’t articulate, and as an adult learned that I was conceived in the San Juan Islands. The idea of the place became even more imbued with mystique for me after learning it played an important role in my own origin story. Before traveling there, my imaginings of the region were moody, rainy scenes that came mostly from Twin Peaks and my parents’ stories of living briefly in Seattle. On my first trip to Washington, I was not specifically looking for the forests, but that is where I found myself again and again. In the Hoh and Quinalt rainforests of the Olympic Peninsula, I felt an intense sense of contentment and enchantment that harkened back to a more childlike or primitive capacity to indulge the imagination, and began trying to capture the essence of this experience in photographs. Though I returned many times to the Pacific Northwest, I also started to explore other American forests as I began thinking more universally about the varied and branching experience of humanity in relation to the forest – its place in out imaginations and myths, our histories and sciences.

In preparation for this work did you spend time with any particular culture’s myths of the forest?

There’s hardly a culture that hasn’t imbued the forest – or at least the tree – with importance and symbolism. I did research many of these later on in my process, but the ones I spent the most time thinking about while shooting were the ones I was already the most familiar with, the ones that have informed my own perception of the forest since I was a child: European fairy tales, Native American myths and legends, and non-native American folklore.

Humans are sparsely seen throughout Sylvania, often from a distance or obscured. What role does the human presence play in this series?

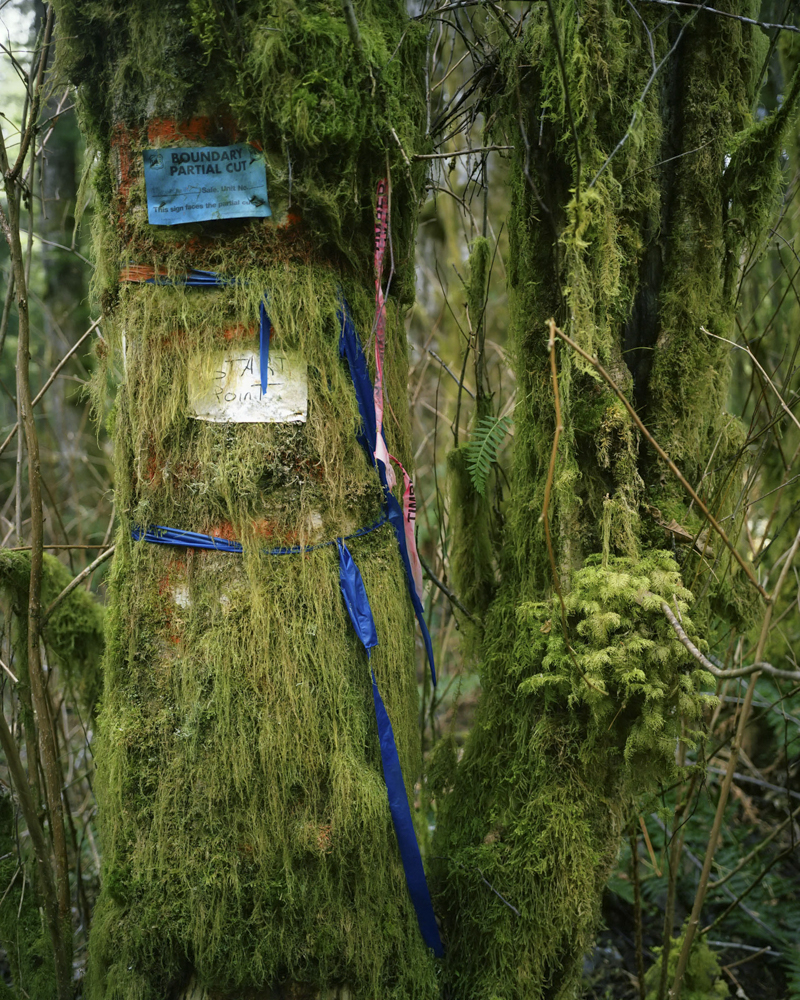

One of the overarching themes of this work is the relationship between humankind and nature, so humans have to show up in some capacity, but I wanted the project to echo my own experience of being in the forest. At the most basic level, the majority of the photos don’t have people in them because the woods are a lonely place and I didn’t run in to all that many people. I did, however, often run into traces of people, and there are many images where the human presence is implied through something left behind – an overgrown satellite dish, signs of a fire, markers left on trees – that interrupts the illusion of primal, untouched beauty and reminds us how we use the forest, and abuse it, in the modern age. When people are present, they exist as I found them: sometimes exploring the forest and sometimes exploiting it and sometimes lost in it (the exception to this is the few self portraits, which of course are staged and are included to reflect my personal journey). Then there are many images without any kind of human presence besides the implied presence of the viewer. These are sublime and ominous settings into which I hope the viewer projects themself, getting lost in a forest land of their own imagination.

While the compositions and qualities of light vary, the images contain a consistent ethereality. What did your shooting, selection, and editing process look like? Did you have firm ideas surrounding presentation and theme from the onset or did ideas develop over time?

My ideas always develop over time – whenever I have a concrete idea of how a project will go it seems to get turned on its head, so I’ve learned to be comfortable collaborating with chance. With Sylvania, I fashioned my shooting process after the fairy tales that were so influential to it, imaging myself on some sort of hero’s quest, going into the enchanted forest in search of adventure and the unknown. The treasure I returned with, of course, was my photographs. Except for a few self portraits, the photos could all be classified as documentary. They have been curated into a selection, however, that references reality more obliquely than typical photojournalistic images in order to let the imagination play. When editing, I was looking for real, sublime moments in the contemporary forest that remind us why generations have thought it a place of magic. Of course, not every single photograph I took contained that magic, or ethereality. Straightforward images of clearcuts and hikers, etc., were mostly banished in favor of images that somehow relate to the forest on a more psychological level.

How does your work as a videographer intersect with your photographic practice? What aspects remain separate?

I view these as totally separate practices; the way I compose a scene and a general knowledge of how cameras work are really the only places where I feel these two intersect. I started working as a videographer after I was well into my photography career, and I usually work with my husband, a documentary filmmaker, on documentary projects. I enjoy working as part of a team (since photography is a solitary pursuit for me), bringing my artistic vision to the moving image, and exploring continuous character-driven stories in film, but it is not my natural instinct to work in a time based medium. My personal work is always still imagery, which can be a bit more vague and free from a clear, connected timeline. Though I got my start studying photojournalism and though documentary work in the broadest sense is my primary concern, I have learned I am most comfortable on the edge of it, straddling the line between fact and fiction, and making images that ask more questions than they answer.

Bookmaking allows for reexamination and provides the opportunity for both artist and viewer to see the work with fresh eyes. What new revelations came to light during the process of making Sylvania into a monograph?

Since literature was so influential to this project, and the book is the main vehicle of literature, I always envisioned Sylvania becoming a book. In fact I made a mock up in grad school for my thesis exhibition, which became the starting blueprint for the monograph published a few years later. During the bookmaking process, I realized with delight how similar viewing the book is to walking through a dense and unknown forest. Its layout is not unlike the sprawling and chaotic nature of the forest: you can take the sequential path laid out for you, or you can choose a divergent and unmarked trail by flipping through the images at random, as we all so often do. The photos lead you deeper and deeper into the woods, but just when you think you are at the heart of darkness there will be a trail marker or a clearing, a bit of blue sky beyond the canopy, or a peek into civilization on the other side of the arboreal fringe. Every so often there will be encounters with other people, but most of the time the viewer is alone in the woods.

The process of making the book also allowed for the addition of a text component to the project. It was my distinct pleasure to collaborate with the late Brian Doyle, who generously agreed to write some words for Sylvania. He observes, “There are stories in the shadows, in the forest, flitting through the trees. How many fables and myths are set in the forest? The forest is where the possible lives. The forest is beyond the reach of sense and reason. The forest is not a place for logic and culture and civilized opinion. The forest is ancient and itself. The forest is hidden life and deeper secrets. Anything might live there and probably does and the only way to find out is to slip beneath the eaves and vanish into it exactly the same way you vanish into a story.”

Anything else you’d like to add?

I’m really happy that five years after this project came out as a monograph and eight years after I started shooting it, Sylvania is still relevant and engaging enough for you to want to interview me about it. I was trying to create something timeless, and perhaps I did. Today even more than when I started the project we can see how imperiled our planet is as the result of human activity, and deforestation is a big contributor to the escalating climate crisis. Though Sylvania doesn’t have an obvious environmentalist agenda, I do hope the images cause people to reflect on their relationship with nature and our collective responsibility to do no harm to it, so that generations to come can be safe and secure enough to continue to be awed and inspired by the forest and the rest of the natural world.

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

McCall Hollister in Conversation With Douglas BreaultMarch 6th, 2026

-

Binh Danh: Belonging in the National ParkMarch 4th, 2026

-

Landscape ReEnvisioned Exhibition At the Monterey Museum of ArtFebruary 26th, 2026

-

Olga Fried: Intangible EncountersFebruary 18th, 2026

-

Juliette Ludeker: Somewhere You Can Never GoFebruary 16th, 2026