Matthew Finley: The Shape of Us

Projects featured this week were selected from our call-for-submissions. We will be accepting new projects for review from April 4th-10th, 2021. Today, we are looking at the series The Shape of Us by Matthew Finley.

Whether using the handcrafted processes of tintype and ambrotype photography to echo our indelible and invariable histories, the more recent cousin to those techniques, instant film, or digital, Matthew Finley strives to connect to the viewer on an intimate and emotional level while at the same time creating art that is both authentic and beautiful. Working with these moody processes, he is able to create photography-as-object: one of a kind, original pieces. His work has shown in multiple galleries across the U.S. and is in the permanent collection of the Museum of Contemporary Photography, Columbia College Chicago, Chicago, IL, among others. His images have also appeared in publications including Oxford American, Shots Magazine, and Plates to Pixels where he won the Juror Award in The Visual Armistice 10th Annual Juried Showcase. Photographs from Matthew’s series, The Shape of Us, are available for purchase through Boys! Boys! Boys!.

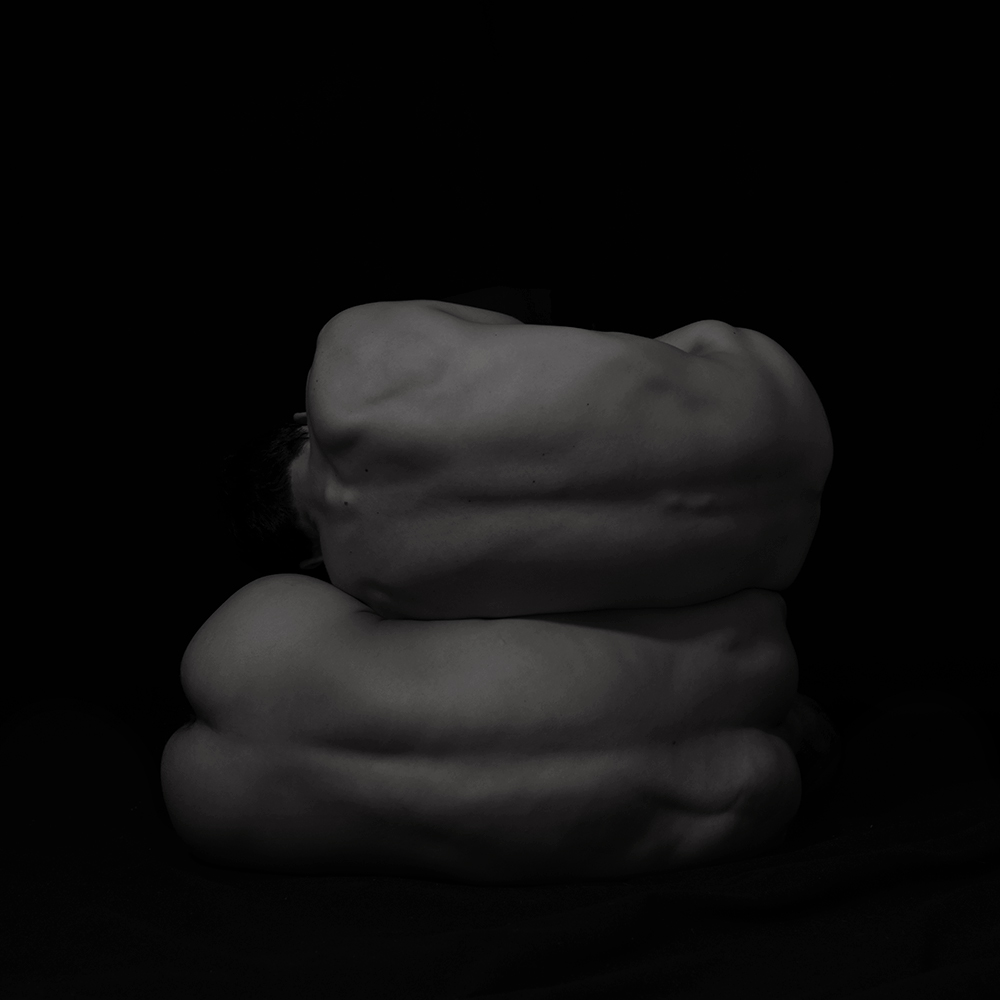

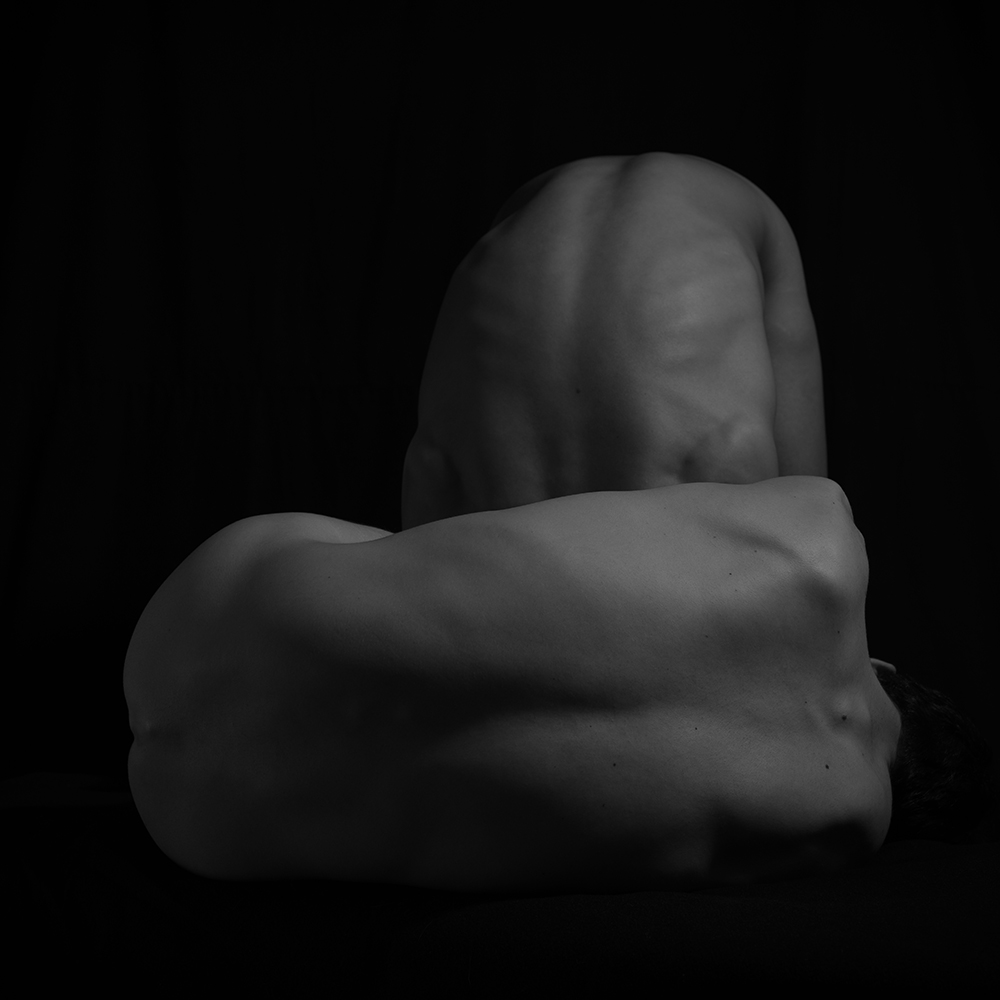

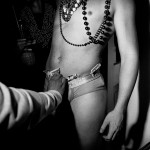

The Shape of Us

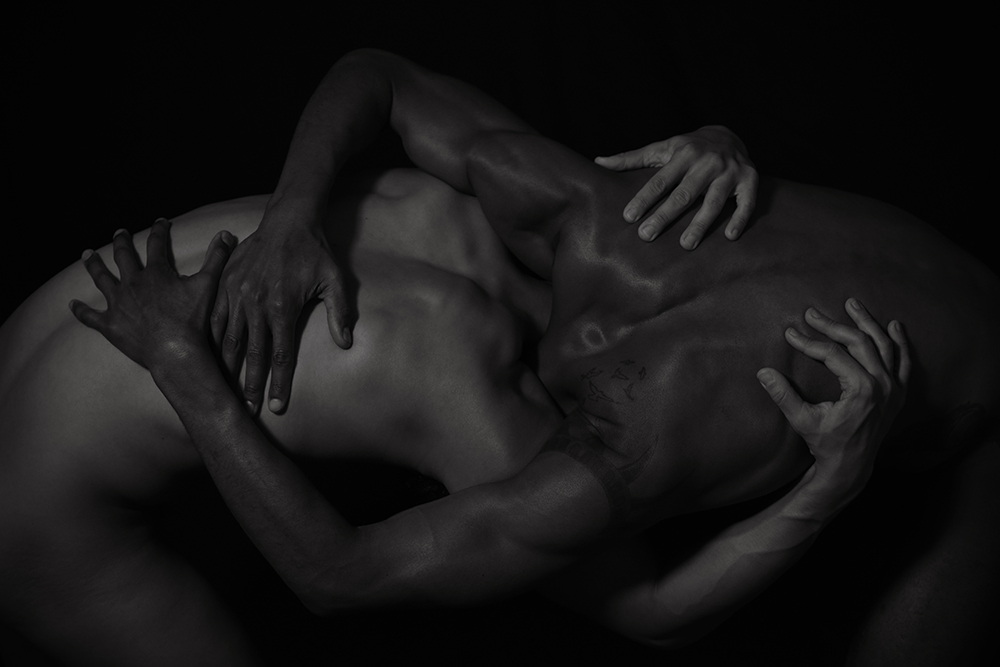

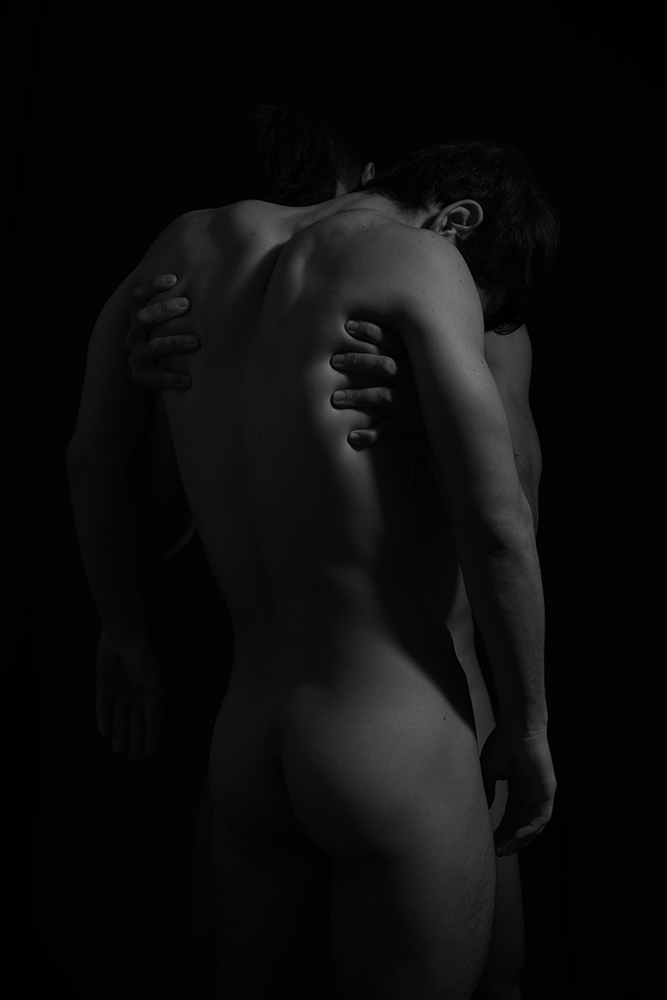

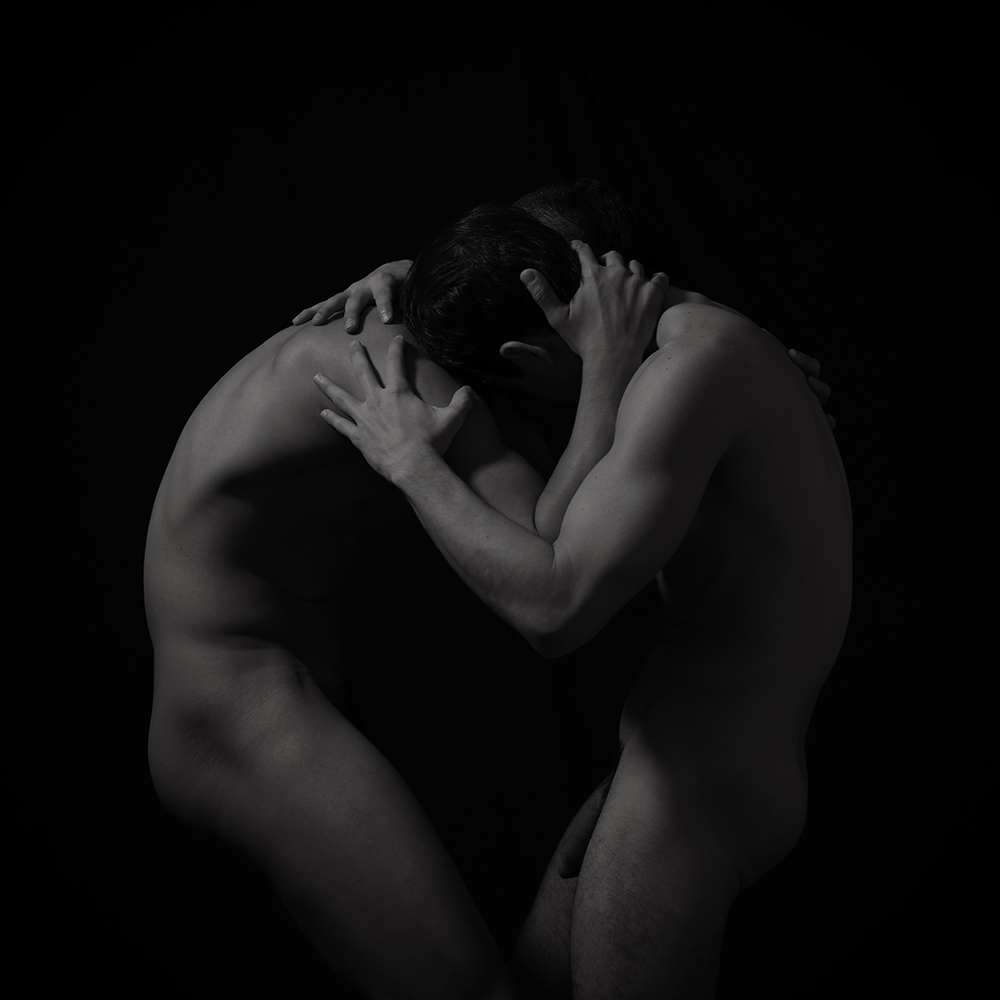

This series is a testament to the beauty that can be created between two men. Inspired by my own long-term relationship, I sought to construct and celebrate the strength, complexity and intimacy possible, while purposefully adding positive gay representations that were practically nonexistent while I was coming out as a young gay man. Lacking in same-sex relationship examples, I was unsure I would ever experience this type of closeness.

While our society has grown and changed a great deal since I came out over twenty years ago, there are still many people today that believe images like the ones I am creating are wrong or perverse. Reflecting emotions that we all experience—intimacy, connection, and acceptance—I aim to forge a moment of recognition and understanding.

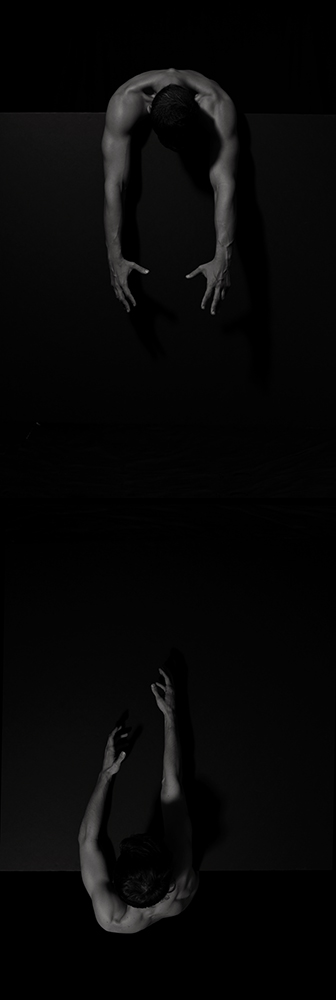

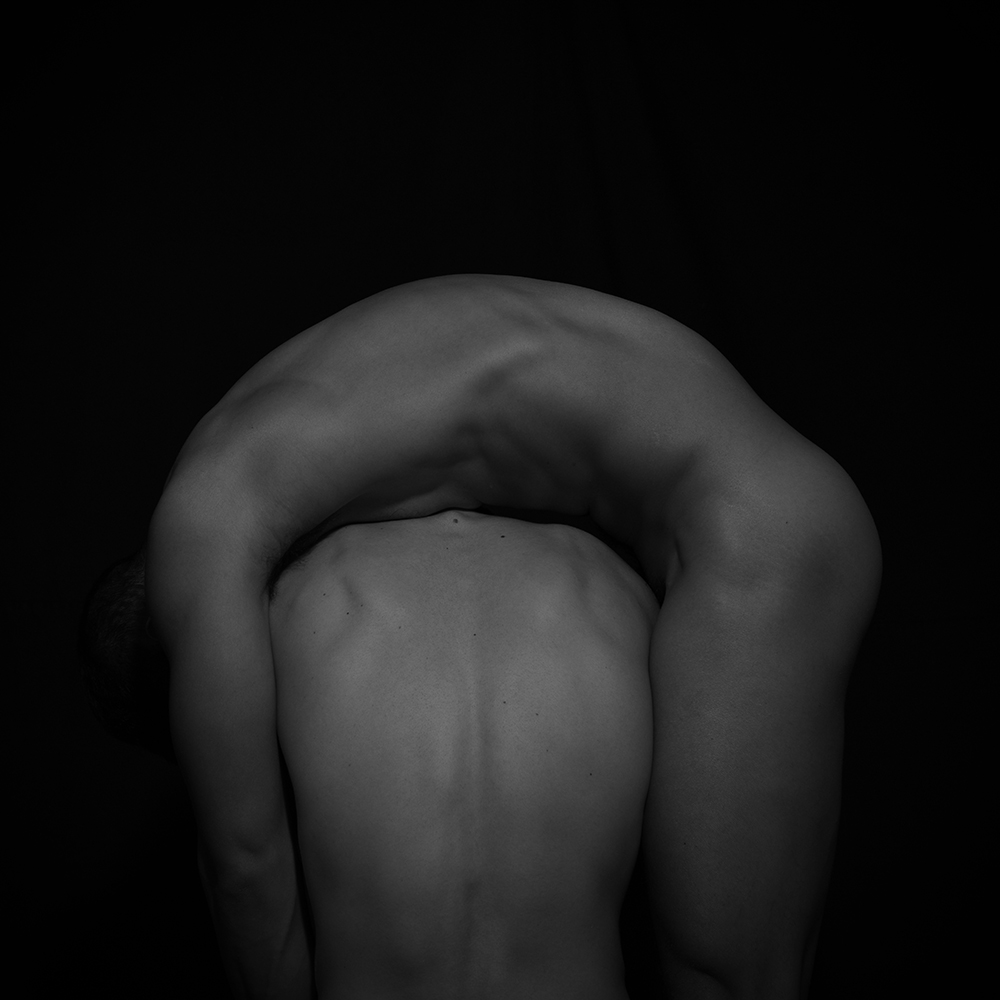

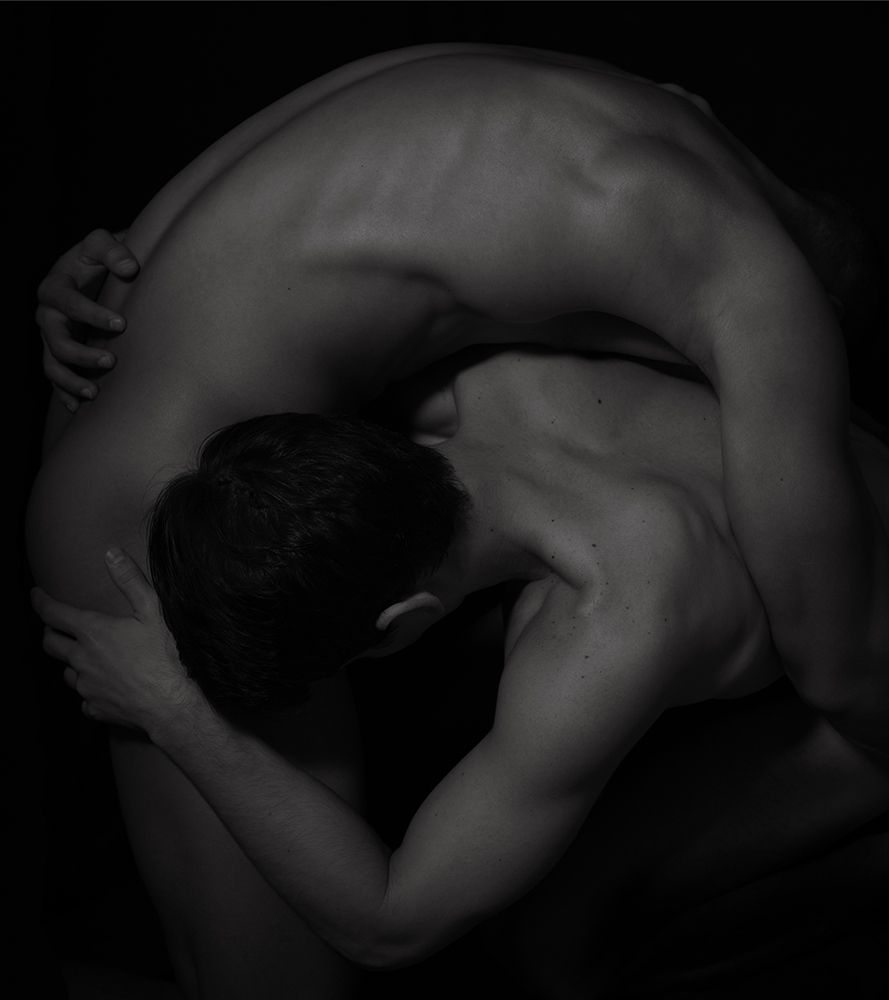

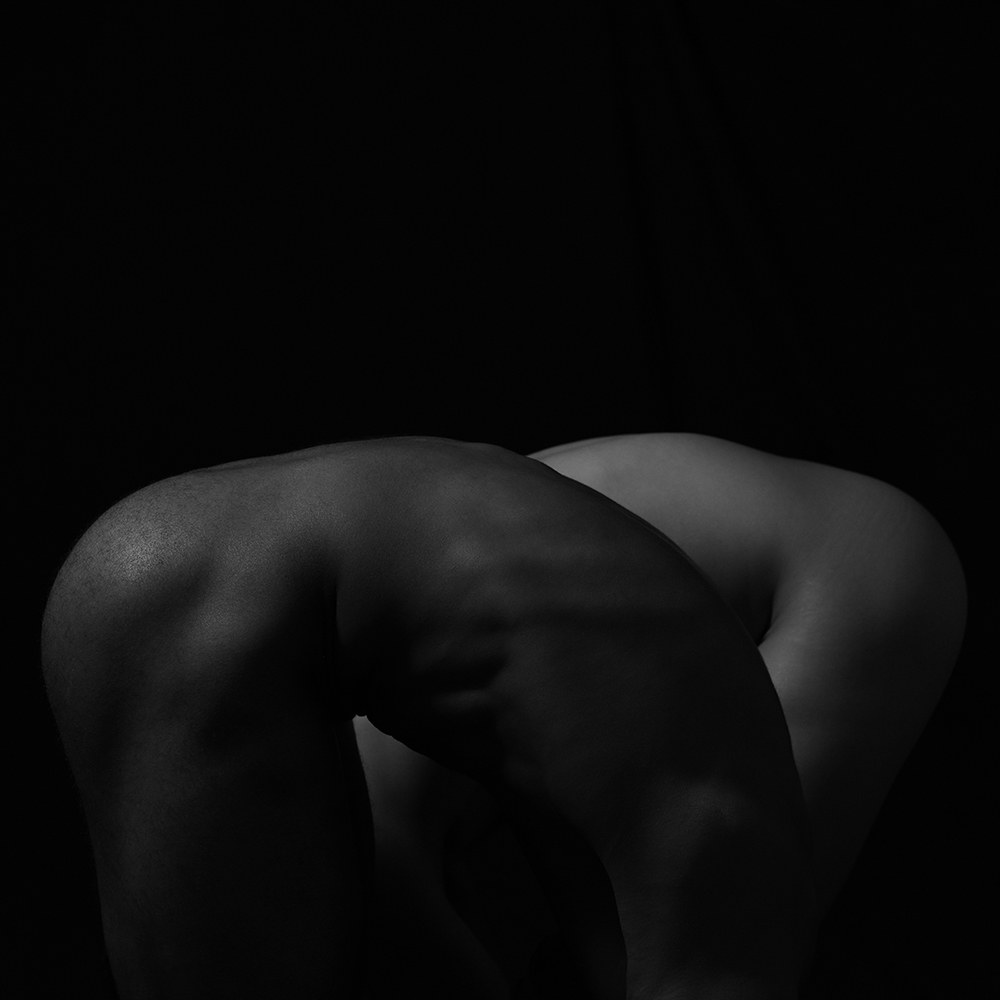

Using bodies in both emotional and abstract relationship, I explore the push and pull that can happen over time as two lives come together to create a unique, new shape that hadn’t previously existed. It is in this spirit of creative effort that I carve out this place for a tribute to the beauty of connectedness.

Daniel George: I am interested in the beginnings of this project. It is evident that something like this had been on your mind for quite some time, as you reference your earlier life and current, long-term relationship. What prompted you to begin making the work?

Matthew Finley: The photo series I created previous to The Shape of Us focused on my past, coming out, familial struggle and acceptance, so it felt like a natural progression to investigate a more recent part of my life: my 12-year relationship with my husband. I was thinking about our evolution, how it took me time to trust that he wasn’t going to change his mind and disappear all of a sudden. How we approach most things differently but because of that we teach each other patience and new perspectives. The effort it takes to keep all the external stresses and obligations from taking focus away from what is most important, our connection and support of each other. Investigating this idea of a relationship over time between two men in love, distilling it into form and gesture, timeless and free from distraction was my desire.

My style has had what some might call a classic, structured composition, so that is where I started with my two subjects, one light source and a black background. Not long after I began my exploration, I started a project workshop with Susan Burnstine at the Los Angeles Center for Photography, and she encouraged me to simplify my compositions even more and reassured me that what I intended was coming across clearly. That support and feedback was very helpful.

DG: In your artist statement, you write that this project was created, in part, as a response to the lack of work like this when you were a young man—suggesting that if you would have been able to see photographs of this nature, it would have been beneficial to you. Would you share your personal insights on the importance of representation in photography/art/culture in general?

MF: We have to remember that until recently there were few queer relationships out in the open to look to. Before I came out, my sheltered exposure to the queer community was largely from the church (“It’s a sin!”) and what I saw in the media. And the latter was pitifully brief: AIDS reporting, or the yearly clip of irreverent Pride celebrations framed as strange and hedonistic. After I came out in the early 90’s and became a part of the queer community in Los Angeles, the consistent imagery of two gay men that I was exposed to was largely just sexual. I’m sure there were loving long-term relationships, but I didn’t know any personally and they sure weren’t in the media. If images like mine, with loving, romantic themes had been more prevalent, they could have stood as evidence that those things were possible, they could have pushed us to invest more of ourselves, given us futures to imagine. Maybe I wouldn’t have struggled with bouts of depression or felt so lonely.

Looking back now, it’s clear how society at large defined gay representation as diseased deviants. It took activists, artists and many, many people coming out over many years to reframe our representation simply as people, people just like everyone else with the same hopes and dreams. Representation plays a huge role. It can give hope and strength to the marginalized and it can educate the majority. I’m so glad there are many more artists and projects now that young LGBTQ+ people can experience, see themselves reflected in, and know that they are not alone. If there is even a small chance that my project does that for some young person, it will have served its purpose.

DG: In a way, it feels that through this work you are attempting to connect with that younger version of yourself—the one who was unsure of “ever experience[ing] this type of closeness”—as depicted in your photographs. Did working on this project provoke any sort of dialogue with yourself? Did you discover anything as a result?

MF: Like many queer people, I had a lot of stress and heartbreak during my coming out experience, but in a way, I have been able show my younger self that it was worth it withThe Shape of Us. Feeling impatient with life, working through feelings of self-worth, and releasing resentment of my family have all gotten me to the place I am at today and I’m very grateful for that. Looking back, I can see the road so much clearer than when I was just starting on it. I can see how I stumbled by repeatedly picking the wrong kind of guys, but proud of my younger self’s tenacity and ability to keep pushing forward.

One of my concerns when I was starting this work was that it might be so personal to me that it may only appeal to gay men, but as I worked through the process and with the help of critiques, I realized that the universal themes and emotions transcended the specifics and could still move a wider audience. And that connection is why I make art in the first place.

DG: What inspired your visual approach, the focus on geometry, and the allusion to perfect shapes?

MF: Photographers I admire influence my work in direct and indirect ways. I’m inspired by Sally Mann’s emotional power and honesty and George Platt Lynes’ simplicity and grace, to name a few. A year prior, I went to Italy for the first time so I was thinking a lot about sculptures and Renaissance art. I wanted to create a timeless space that was both intimate and mysterious, compositions that were strong and beautiful. The focus was first on the shapes we could create. Later, when I was thinking about titles, the metaphor of geometry was a way I could name the shapes while leaving room for interpretation. I didn’t want to name the images after emotions or situations that would interrupt what the viewer might bring to the image themselves.

For me, it’s not so much about a perfect shape as it is two people or lives coming together to create a new shape that didn’t exist before. Their own shape, unique to them and for them. A shape that will change as they move closer together or further apart, as one stumbles and the other holds them up.

DG: You write how with this work, you “aim to forge a moment of recognition and understanding.” As you mentioned, society has changed a lot since you came out twenty years ago. Perhaps we are not in a watershed moment, yet positive gay imagery is still critical in order to maintain a greater sense of compassion and empathy. How do your photographs accomplish this?

MF: I hope that someone who hasn’t been exposed to images of queer male love and intimacy might see this work and get drawn in by the beauty and identify with the emotional content. I hope it sparks in them some recognition and realization of how we are all the same. We all have the same desire for love, closeness and intimacy. When we realize that there is no room for “othering” one another, there will only be room for compassion and understanding. That’s the world that I want to live in. While there is a lot more positive gay imagery and art now than there was thirty years ago, it is still a small amount in caparison. But it is growing, and I am honored to add to it.

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

Christa Blackwood: My History of MenJuly 6th, 2025

-

Jeanette Spicer: To the Ends of the EarthJanuary 21st, 2025

-

Smith Galtney in Conversation with Douglas BreaultDecember 3rd, 2024

-

Tarrah Krajnak: Master Rituals II: Weston’s NudesMay 30th, 2024

-

European Week: Sayuri IchidaMarch 8th, 2024