Deborah Espinosa: Living with Conviction: Sentenced to Debt for Life in Washington State

©Deborah Espinosa, Keshena, of Tacoma, Washington, holds the photo of her son, which she kept with her in prison to remind her of what she could lose while in prison.

One of the many hidden aspects of the criminal system is that, at sentencing, people are often assessed fines and surcharges. Through Deborah Espinosa’s eye-opening work, Living with Conviction: Sentenced to Debt for Life in Washington State, we see how, even after release, those fees and the accrued interest prohibit people from ever leaving their prison experiences behind and, in fact, keep them forever reminded of, and paying for, their conviction.

©Deborah Espinosa, “They suffer, too. For everything I have done in the past, they suffer for now. My past is haunting me,” says Keshena of Tacoma. She is a mother to two teenage boys – the older son is on his way to prison. Her husband is also serving time, as is her step-father. Due to several convictions for forgery, which included 4.5 years in prison, Keshena now owes approximately $50,000 in legal financial obligations.

Deborah Espinosa is an artist and attorney, born in southern California to a Mexican father and Norwegian mother. She now lives in Seattle, Washington, combining her legal and multimedia storytelling skills to help advocate for the rights of people from poor and marginalized communities in Washington. She also works to strengthen those rights by providing legal technical assistance to state and national governments, primarily in Africa. She believes that multimedia storytelling is one of the most compelling advocacy tools for reform of unjust law.

Before launching Living with Conviction, Deborah served as staff photographer and staff attorney for the international NGO Landesa, bringing to life the organization’s mission of securing land rights for the world’s rural poor through photographs, photo essays, and short videos.

Deborah’s ongoing documentary project, Living with Conviction: Sentenced to Debt for Life in Washington State confronts how Washington has been sentencing people to not just prison but to a lifetime of debt. In partnership with formerly incarcerated individuals, the project raises awareness about and advocates for an end to courts’ imposition of fees, fines, and victim restitution on criminal defendants as part of a criminal sentence. Through photography exhibits, recorded personal narratives, and community conversations, the project exposes how this court debt – with 12% interest – perpetuates cycles of poverty and incarceration, disproportionately impacting the poor and families of color.

Living with Conviction goes beyond the polarizing headlines and statistics of mass incarceration to share stories of common humanity: stories of families torn apart by the criminal justice system; stories of addiction, mental illness, abuse, and trauma, but also stories of recovery, resilience, healing, and love.

Deborah is a member of the inaugural cohort of We, Women artists, recognizing her use of photography for community engagement and social impact. Her work has been exhibited in Seattle and San Francisco galleries and is currently in a 10-year exhibit at the Canadian Museum for Human Rights.

This summer, Living with Conviction will be part of a We, Women traveling outdoor exhibit in six states throughout the country.

Deborah is a graduate of the Rocky Mountain School of Photography, and she holds a J.D. from the University of Washington School of Law, a M.A. from the Jackson School of International Studies at the University of Washington, and a B.A. from the University of California at Berkeley. Her work is online at: www.SameSkyPhoto.com and www.LivingwithConviction.org.

Instagram: @sameskyphoto @livingwithconviction

![“Whether we are incarcerated or not, we still are living marginalized lives. . . . You are taking away access to the American dream. Everybody should be entitled to that – to be able to work hard and see the benefits of their hard work.” At 17, Carmen of Yakima aged out of foster care, pregnant and addicted to heroin. After a series of convictions for prostitution and check fraud, it was the threat of losing rights to her five children that motivated Carmen to turn herself in and begin the road to recovery. “I [didn't] want my kids to go through life thinking I didn’t fight for them," says Carmen. She’s paid $32,000 in LFOs, working three jobs.](http://lenscratch.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/03/Espinosa_SS8_0338-.jpg)

©Deborah Espinosa, “Whether we are incarcerated or not, we still are living marginalized lives. . . . You are taking away access to the American dream. Everybody should be entitled to that – to be able to work hard and see the benefits of their hard work.” At 17, Carmen of Yakima aged out of foster care, pregnant and addicted to heroin. After a series of convictions for prostitution and check fraud, it was the threat of losing rights to her five children that motivated Carmen to turn herself in and begin the road to recovery. “I [didn’t] want my kids to go through life thinking I didn’t fight for them,” says Carmen. She’s paid $32,000 in LFOs, working three jobs.

Living with Conviction: Sentenced to Debt for Life in Washington State

Living with Conviction: Sentenced to Debt for Life in Washington State confronts how the State of Washington has been sentencing people to not just prison but to a lifetime of debt. In partnership with formerly incarcerated individuals, Living with Conviction shares the impacts of court-imposed debt, accruing 12% interest, through portraits, personal narratives, and community conversations.

“I didn’t know that I was pleading guilty to a lifetime debtor’s prison,” says Michael, a 61-year old, disabled Native American veteran. In addition to a five-year prison sentence, the court held Michael liable for legal financial obligations (“LFOs”) in the amount of $11,614 at 12% interest. Ten years later, Michael is drug-free, is primary caregiver for his 87-year old aunt, and collects a monthly veteran’s disability pension of $1,070. Since his release, Michael has consistently made $75 monthly payments, which the State has applied only to the interest accrued. As a result, today Michael owes $17,438.57 in LFOs. If he misses a payment, he can be arrested. For Michael, and the 7,500-plus individuals reentering Washington communities yearly, such debt is physically, mentally, emotionally, and financially crippling. This policy criminalizes poverty. It keeps people from low-income communities and communities of color disproportionately shackled to the criminal justice system for life.

This project goes beyond the polarizing headlines and statistics of mass incarceration to share stories of our common humanity. We share stories of families torn apart by our criminal justice system. We share stories of addiction, mental illness, abuse, and trauma, but also recovery, resilience, healing, and love.

A 2018 legal reform of LFO law in Washington was a step in the right direction but failed to provide relief for hundreds of thousands of people with LFOs, thus keeping them shackled to the criminal justice system for life.

To me, LFO policy is unconscionable.

I am an artist and attorney, born and raised in southern California to a Mexican father and Norwegian mother. I now live in Seattle, Washington, combining my legal and multimedia storytelling skills to help advocate for the rights of people from poor and marginalized communities in Washington. I also work to strengthen those rights by providing legal technical assistance to state and national governments, primarily in Africa. She believes that multimedia storytelling is one of the most compelling advocacy tools for reform of unjust law.

©Deborah Espinosa, Carmen of Yakima with her daughter and granddaughter at the community garden where they supplement their food budget. Even with three jobs, Carmen must also resort to going to food banks to ensure that she does not miss an LFO payment.

©Deborah Espinosa, “In order to be in compliance with the LFOs and the fines, it created poverty for me that wouldn’t have otherwise been there. Accountability is important, . . . but the money piece is damaging and very sad, very sad. . . .I feel like they own me.” ~ Maria Like mother, like daughter, says Maria, of Burien, Washington. Single, teenage mom. Subsidized housing. Working hard. Addicted to heroin. She was convicted twice. In addition to her prison sentences, the court required Maria to pay $4,000 in LFOs. After she was released, she was trying to support her two children on $9 per hour while at the same time make $25 monthly LFO payments. When the LFO balance reached $13,000, a collection agency started garnishing her wages.

©Deborah Espinosa, “I was working at a gas station and there was an incident. . . I was asked to write a victim’s statement. . . . About two to three weeks after that I got a knock at the door from police officers. They had a warrant out for my arrest. For not paying for my supervision and fines. . . . . I was not paying anything. So they arrested me and took me back to the jail. I had no money. I was making whatever minimum wage was, trying to pay my bills and child support. . . . I think I did 14 days in jail. I lost my job.” Today, Michelle* still chooses to not make payments towards her debt, instead using her income to support her four children and pay her graduate school tuition. *name changed

©Deborah Espinosa, “I was terrified I’m going back to prison. The only thing that was going to keep me from these kids now was going back to jail. The only thing that was going to keep me going back to jail is because I didn’t pay my LFOs.” Following prison, Michelle, of Spokane, Washington, was able to reunite with her children, even though she had no beds, no furniture, a now car. A generous member of Michelle’s mother’s church donated $5,000 to her so she could buy a car. Instead, Michelle used the money to pay off her LFOs, out of fear that she would be arrested for failure to pay. She is confident that if she had not paid off her LFOs, she and her family would still be one paycheck away from homelessness.

©Deborah Espinosa, “Having $39,000 in fines doesn’t affect somebody who doesn’t care. It doesn’t affect a junkie in a basement shooting up. . . . But for somebody like me, doing everything they are supposed to be doing, and owes more in legal financial obligations than in student loans, and can’t buy a house, can’t help send their children to college, can’t do more than get by. People should care. I did the crimes and I did the time and I’m still paying for it 16 years later in every aspect of my life. . . . ” says Sabrina, mother of 7.

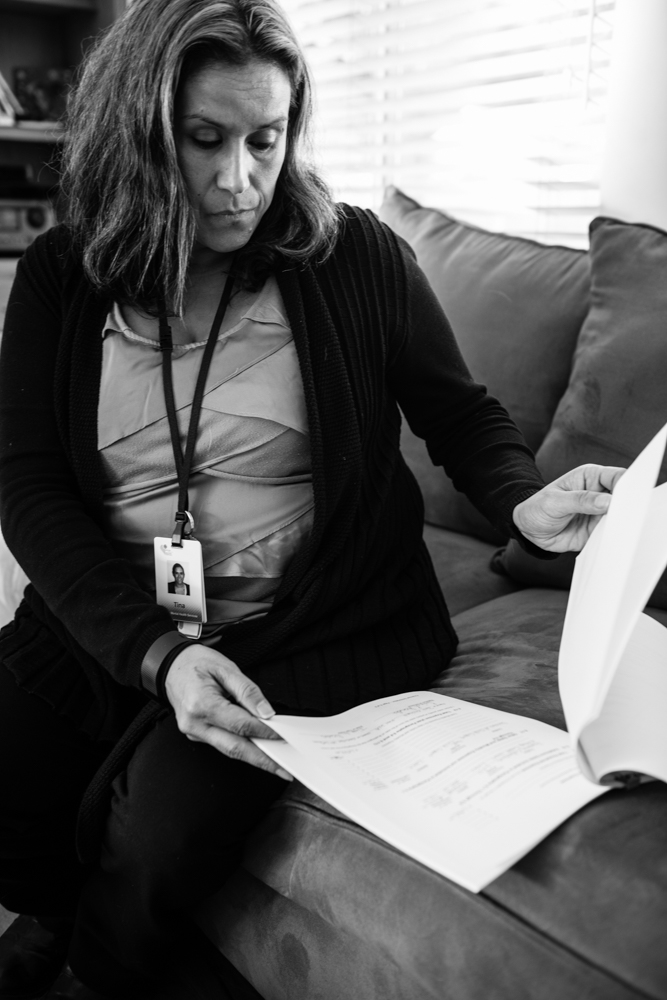

©Deborah Espinosa, “Oh my gosh, I wanted to scream and jump for joy in the courthouse. . . . There is light at the end of the tunnel.” ~ Tina That’s how Tina, of Bremerton, Washington, felt when the judge agreed to waive the 12% interest that had accrued on her $50,000 LFO debt. She filed that motion because it was a significant hardship to continue paying $325 per month. She and her husband continue to pay $200 per month towards their combined LFO debt.

!["My LFOs could ignite at any second. . . . I was telling my 16-year old, 'I just want you to know where I’m going, what I’m doing [the LFO interview], and that I’m taking a risk. It could be his birthday, it could be Easter, it might not be but I could be arrested after this. He was like, 'You really need to wear your superhero shirt then..," says Renee, a homeless Native American mother of six who is a two-time survivor of domestic violence.](http://lenscratch.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/03/Espinosa_SS8_2511-.jpg)

©Deborah Espinosa, “My LFOs could ignite at any second. . . . I was telling my 16-year old, ‘I just want you to know where I’m going, what I’m doing [the LFO interview], and that I’m taking a risk. It could be his birthday, it could be Easter, it might not be but I could be arrested after this. He was like, ‘You really need to wear your superhero shirt then..,” says Renee, a homeless Native American mother of six who is a two-time survivor of domestic violence.

©Deborah Espinosa, “It’s just barrier after barrier after barrier. It’s death from a thousand paper cuts. It is a life sentence.” ~ Sue Sue, from Seattle, Washington, endured a childhood filled with poverty and abuse. She married an abusive man and turned to drugs. Convicted, she served 15 months in federal prison, during which the State of Washington also charged her. She came out of federal prison owing $30,000 (with no interest) and pled guilty to the state charges, along with over $4,500 in LFOs. She makes a $15 payment every month.

©Deborah Espinosa, “Nobody ever said, “What’s going on with you?’ I was a single mom and had just lost custody of my children.” Julie’s conviction is a direct result of her mental illness. Soon after a bipolar diagnosis, for which she was given new medication, she walked out of Walmart with more than $750 worth of groceries in her basket — without paying for them. She put them in her trunk — food, cat litter, laundry soap — and drove home. By the time the police arrived at her house (everyone knew each other in her small town), the groceries were still in her car — even the pot roast. Instead of going to court, Julie attempted suicide. She was convicted of theft in the second degree — a class C felony. As a first-time offender, she did not go to prison but was assessed $1,500 in LFOs.

After spending 18 years as a public defender, Sara Bennett turned her attention to photographing women with life sentences, both inside and outside prison. Her work has been widely exhibited and featured in such publications as The New York Times, The New Yorker Photo Booth, and Variety & Rolling Stone’s “American (In)Justice.”

Like the women she photographs, Bennett hopes her work will shed light on the pointlessness of extremely long sentences and arbitrary parole denials. To bring Life After Life in Prison, The Bedroom Project, or Looking Inside to your community, please contact her. IG: @sarabennettbrooklyn

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

Anastasia Tsayder: ARCADIAJanuary 28th, 2026

-

Ed Kashi: A Period in Time, 1977 – 2022January 25th, 2026

-

Greg Constantine: 7 Doors: An American GulagJanuary 17th, 2026

-

Kevin Cooley: In The Gardens of EatonJanuary 8th, 2026

-

William Karl Valentine: The Eaton FireJanuary 7th, 2026