Jenia Fridlyand: On Domestic Life

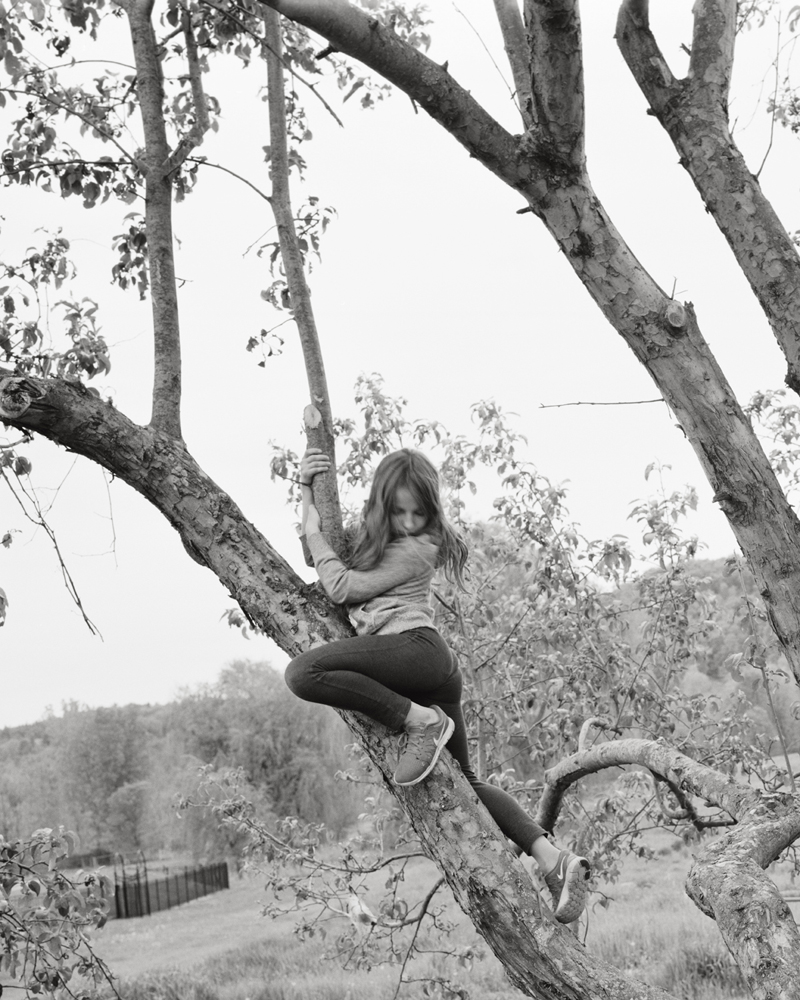

At its opening, Jenia Fridlyand’s monograph, Entrance to Our Valley, shows a world just before waking. Sunlight shines through a tangled tree outstretched like an ancient hand blotting out the burning star. A dense patch of fog retreats back into the forest revealing a field defined by a snaking fence line. Thirdly, we see a child. Eyes closed and nestled into the nook of a striped pillow. Awakening before the rest of the world is a unique sensation. The day has not yet been dulled by the harsh familiar light of noon nor the tired wheel of work and human progress. Before the waking world every blade of grass is kissed by dew. Birds and insects begin their morning song and every inch of light and shadow reads exceptional. What strikes me most about Fridlyand’s work is her ability to preserve this fleeting sense of singularity throughout. In Entrance to Our Valley we see what most farmers see; a quiet house and growing harvest. Yet, Fridlyand’s carefully considered presentation bestows these scenes with a sense of the miraculous. I can recall the first time I saw her image of vertically strung fly tape. I gasped aloud gazing up at my own dangling strip, wondering what other miracles had been lost on me.

Entrance to our Valley is available for purchase from TIS Books at the link below.

https://www.tisbooks.pub/products/entrance-to-our-valley

Jenia Fridlyand (Moscow, 1975) is a photographer and educator based in New York City and the Hudson Valley. Her photographs and books have been exhibited in the United States and abroad. Fridlyand’s artist’s book Entrance to Our Valley was shortlisted for the Paris Photo – Aperture First Photobook Award 2017, and trade editions were published by TIS Books in 2019 and 2020. She is represented by Galerie Wouter van Leeuwen, Amsterdam.

In 2016, Fridlyand co-founded Image Threads, a non-profit collective whose mission is to bring together artists, educators, and bookmakers in communities around the world for a mutual exchange of ideas and experiences related to the photobook. She organized and taught workshops and courses in Ukraine, Georgia, Iceland, Canada, and Cuba, and is the chair of the Photobook Long Term Program at Penumbra Foundation in New York.

Fridlyand studied photography at Centre Iris and Université Paris VIII, and holds an MFA from the University of Hartford’s International Limited-Residency program.

Entrance to our Valley

Entrance to Our Valley is a body of work conceived as the story of Chekhov’s “Cherry Orchard” transported to another time, reversed left to right and flipped upside down on the ground glass of my view camera. A century later, on the other side of the globe, descendants of Eastern European Jews, who were not allowed to own land in Imperial Russia, take the place of hereditary Russian aristocrats, and are attempting to create what the characters in the play lost: an inhabited piece of land, a home, an identity. As the story unfolds, the narrative of our family as first-generation immigrants starting a new life on a farm in New York’s Hudson Valley becomes entwined with the history of this wondrous region itself.

I see in your bio that you were born in Moscow. Did your photographic practice begin in Russia or did imagemaking come into your life after immigrating to the US?

I left the Soviet Union with the family in my early teens and didn’t really become aware of fine art photography until college. I was studying biophysics, but my roommate was a photography major – she taught me to c-print and we often talked about her work. That seed of interest took nearly two decades to fully germinate, and weathered many detours, from scientific research to dancing with a gypsy troupe, until I finally committed to photography when I entered the Hartford MFA program in 2014.

Who and what were some of your early influences? I’d love to hear about photographers you admired as well as any other artists/mediums that helped shape your creative voice.

Some photographers pick up a camera at an early age and it becomes an extension of their body, but many come to photography from other pursuits, and it marks their practice in various, specific ways. My most intense creative interest prior to photography was literature, but I struggled with language: my Russian never had a chance to mature in its native environment, and English still at times feels like a foreign language. One of the most momentous epiphanies of my life was that photography, in book form, can be used in the same way as language is used in fiction: to construct a self-sufficient world. While I can’t put my finger on any direct parallels, I feel that Russian literature was formative to the way I relate the world. My photographic education, on the other hand, is very American, with the work of Walker Evans, Robert Adams, and John Gossage being incessant wells of inspiration.

The images that make up Entrance to Our Valley were made on a view camera. Why is this way of working important to your practice?

I switched to monochrome film and a 4×5 camera from medium format color when I started working on Entrance to Our Valley, and the change proved seminal for my practice. For one, it slowed me down in a way which made it impossible to be flippant about any image I made and, similarly, made my subjects take the process more seriously as well. Another important aspect of working with a view camera is composing on the ground glass rather than through a viewfinder: the reversal of the image allows for a more direct access to its formal qualities and facilitates building up the composition from the edges in rather than from the center out, a hack that helped me make most of the pictures I find interesting.

In your statement you write that “Entrance to Our Valley is a body of work conceived as the story of Chekhov’s “Cherry Orchard”. Did you set out initially to create a body of images that paired with Chekhov’s work or did the connection develop organically as you were shooting?

I use the “conceptual” framework of a project only to establish some parameters for shooting, and then let the photographic process take over. In the meantime, the “thinking” about the initial impulse continues in parallel, and it’s when the ideas and the pictures begin to correspond in some novel meaningful way does the project draw to a close. The questions I was turning in my mind as I was photographing at our newly acquired farm were mostly related to what it means to be Russian, especially in the particular circumstances of present political changes, our family heritage and current geographic location. One day it dawned on me that those same questions were being addressed in Chekhov’s play, but through the process of destruction, rather than creation, of a home

Was an artist book always the hope for Entrance? Was the design and formatting part of your greater vision for the work or did collaboration with your publisher define the final outcome?

For me, the final form of a project is always a book (with silver prints being mostly the result of working through individual images). I made a few distinct versions of Entrance to Our Valley before the risograph artist edition, which finally felt “right”. When we began collaborating with TIS on the trade edition, the goal was to preserve – through having to change materials, printing method, etc. – the experience of that last version, and I believe we succeeded.

What’s next on the horizon? Where are you focusing your creative energy these days?

The project following “Entrance to Our Valley” was based in Cuba, where I photographed from 2017 to 2019. On my last trip there, just a few months before the pandemic began, I woke up with a start one morning, filled by a feeling that the project is done. The circumstances of the last year and a half gave me a chance to acquire some distance from the work, and while I might still need one more trip to confirm for myself that there are no gaps, I believe that the core of the book is there, and I have been chipping away at the edit in various ways –by making darkroom prints, including the work in smaller publications to see the images in print, etc. I have two other projects which have been fermenting in my mind all this time, but both require travel, so I am holding my breath for the opportunity to work on those. Teaching is also a significant, and wonderfully generative, part of my life now. When I started grad school, the possibility of teaching wasn’t even in the back of my mind, but I quickly realized that I am learning at least as much in my classmates’ critiques as I do in my own. With a couple of them, right after graduation, we founded Image Threads, a photobook teaching collective, and began organizing workshops and longer term courses, focusing on photographic communities where the photobook genre had not yet taken hold. In 2020, in partnership with Penumbra Foundation, we initiated the Long Term Program, an online year-long course for photographers working on a photobook project, which I have been chairing. Both the community of students and guest artists, and the challenges of helping develop book projects, different with every student, have been a real source of sustenance in these odd times.

Anything else you’d like to add?

Thank you so much for featuring “Entrance to Our Valley”. It has been four years since its initial publication, and the project is now solidly in the past for me, so I find it especially moving that the interest in the work is still there for others.

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

J. Lester Feder: The Queer Face of WarMarch 11th, 2026

-

L. Kasimu Harris: New Photography 2025: Lines of Belonging at MOMAMarch 10th, 2026

-

Kiana Hayeri: No Woman’s LandMarch 8th, 2026

-

Review Santa Fe: Leslee Broersma: Tracing AcademiaFebruary 11th, 2026

-

Review Santa Fe: Ilana Grollman: Just Know That I Love YouFebruary 10th, 2026