Ka-Man Tse: narrow distances

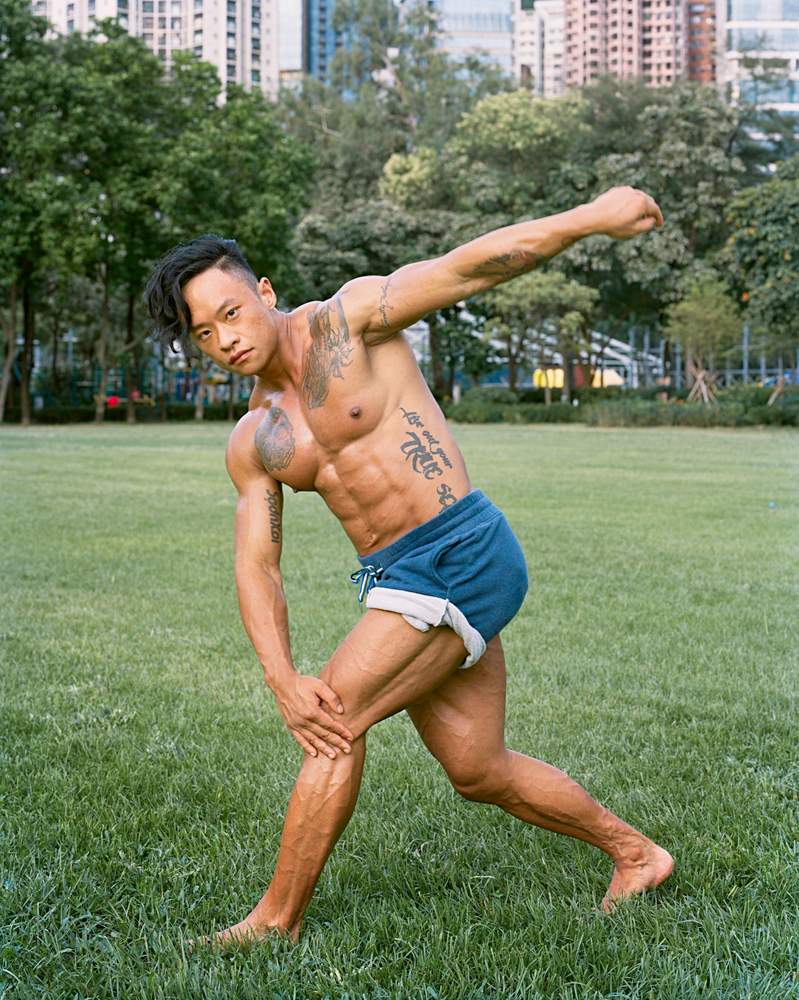

In her project narrow distances, Ka-Man Tse’s photographs linger in spaces tucked away primarily throughout skyscraper-laden Hong Kong and New York City. Included in these realms are quiet, large format portraits of Tse’s subjects and collaborators, whose identities dwell at the intersections between Asian Pacific Islander and LGBTQ communities. Brimming with small gestures, the artist’s images record intimate moments of recognition for the communities she holds close—a significant act in places where connection and privacy is often in short supply. An interview with Tse follows.

Ka-Man Tse has exhibited her work at Para Site, Videotage, Lumenvisum, WMA’s Transition, and Eaton Workshop all in Hong Kong. In the U.S. she has mounted solo shows at Aperture in New York, the Silver Eye Center for Photography in Pittsburgh, PA, and the New York Public Library. In the fall of 2020, she exhibited work at Art on the Stoop: Sunset Screenings at the Brooklyn Museum. She is the recipient of the Robert Giard Fellowship, a Research Award from Yale University Fund for Lesbian and Gay Studies, the Aperture Portfolio Prize, the Aaron Siskind Fellowship, and was a Artist in Resident at Light Work in Syracuse, NY. Curatorial projects include Daybreak: New Affirmations in Queer Photography at the Leslie-Lohman Museum co-curated with Matt Jensen, and Unruly Visions, in partnership with the Hong Kong International Photography Festival, featuring work by emerging LGTBQ photographers in Hong Kong in 2021. Her monograph, narrow distances was published by Candor Arts. She has taught at Cooper Union, Yale, and is currently Associate Director of BFA Photography at Parsons.

Artist Statement

My image-making begins between longing and belonging, place and placelessness. My photographs are fueled by a desire to negotiate multiple and diasporic identities and seemingly disparate worlds – and are made within the intersection of Asian and Asian American and LGBTQ communities, made between Hong Kong and New York, and made through a queer lens.

The photographs in my book narrow distances are made between 2004-2018 between Hong Kong, New York and a few made in Schenectady. The book opens with images from the decommissioned airport, Kai Tak, situated in the heart of Kowloon, and from those pictures, emerge the portraits. Kai Tak, its closing and the transfer to Chep Lep Kok is a symbol of the transition of power from British colonial rule to Beijing. Kai Tak as site of a dislocation and loss also remains a contested site, a synecdoche of Hong Kong, transition, subtraction and development is a permanent condition. In the book, I photograph Kai Tak throughout the years after its decommissioning, from where the towers and structures are in tact to its erasure, to remnants and new developments through the present day. The landscapes are then populated with portraits, and the color palette shifts from grey soot of the buildings and they sky to more warm colors and to interiors. Starting from this place of departure and subtraction, the sequence of images in the book aim to reverse the loss through the building of community and to have it populated with my protagonists, portraits of members of the LGBTQ community in Hong Kong and of my inherited and chosen family. The portraits begin first at Kai Tak, then in the liminal spaces, portraits made outdoors, and then inside homes.

narrow distances – based on a line by Asian American poet Ken Chen, is about longing and belonging, and a recasting of a world. It places the protagonists within and against the landscapes— employing construction, subtraction, density, compression, liminal spaces, as metaphor. The portraits center those who are often marginalized and invisibilized, taking care of Hong Kong, each other and their own communities they have built, occupying and queering space, time, and gesture. In the contested and contingent spaces in the home, in the public realm, holding space and a conversation is an act. Possibilities start with small gestures, clear or coded, taking place in the potentiality of the in-between and everyday. They are made out of a need to occupy the landscape, to hold space, and the frame; to establish a sense of personal space and agency where it is often contested and eroded. In the spaces of contingency, building and renewal, subtraction and redevelopment, a city is in transition; a body and one’s identity is in transition; and this reflects the need to be fluid, agile, plural.

My process involves re-visiting, re-imagining, collaboration and long-engagement. The portraits are made through conversations and interviews, and mental imaging. The photographs function as a product of dialogue centered around each individual’s personal history and concerns. I ask each person to choose a space that has significance; or it is a specific memory that has resonated with them. Active listening, dialogue, and collaboration are important to my process. In a culture and economy where speed and efficiency are valued above all else, I use a 4×5 film camera to slow time, and we build an image together. Using mostly a large format view camera, my photographs propose B-sides: queer narratives and obsessions. The conceptual framework of my work is care and community. —Ka-Man Tse

How and why did you come to photography?

Growing up in Schenectady, New York in the 1980s and 1990s, in a working-class immigrant family – my parents worked in Chinese restaurants – I didn’t have any role models who were artists. Much of the image culture that we consumed at home were from VHS tapes, borrowed, circulated and copied through fellow restaurant workers in the Capital Region – of movies and shows from Hong Kong, mostly mini-series on TVB. My parents would come home with a plastic bag of tapes – from so-and-so, and we needed to return by this time — and we would work through these tapes at night, diasporic candy informal lending library. On the flip side, we had a tiny section of photography books in the Schenectady County Public Library, and I remember falling in love with how Roy DeCarava saw the world, and Berenice Abbott’s landscapes and portraits.

I started making photographs when I was in high school. The first pre-planned photograph I made was a photograph of eggs, fried, placed on the sidewalk, in the summer. What a dumb joke! But in making that photograph, that is — following through with an idea, a whole roll of 35mm film “wasted,” as my mom would say, something happened. I soon became obsessed with photography. (Humor doesn’t really creep back into my work until much later, through video.) I was lucky enough to talk my way into a darkroom – the teacher running yearbook at Schenectady Public High School showed me how to make a print in one quick session. She let me print in the darkroom even though I wasn’t enrolled in her classes. I spent any money I made as a teenager on black and white film and RC paper; I would print after school until the security guard would find me. I realize that I was working on this alone. I say this because I became the artist I am today because of a community, the photo kin, the queer Asian kin. It was also because of Bard, because of the teachers in that program (Stephen Shore, An-My Lê, Barbara Ess) and my classmates. Life-long friends were formed in that darkroom, at Woods. Fiber prints and analog color prints take copious amounts of time, and that communal space of looking, seeing and waiting, and waiting, and working is burned into me. My friends from Bard are still some of the first people I’ll show work to, who I trust deeply.

There is an intimacy and quietude to your image making that, in my head, run antithetical to the personalities of the breakneck-paced, skyscraper-filled cities where your images are set—Hong Kong and New York City. How are you thinking about this contrast, and what are the intended effects of working in such a slow, deliberate way?

For me, slowness is a way to resist. It feels counterintuitive in such a city as Hong Kong or New York. Capitalism is designed to be fast. Both cities are steeped in finance and run by capitalism, oligarchies and developer hegemony. In both, and especially Hong Kong, space is contingent. But precisely because it doesn’t make sense, and is inefficient, slowness is the best foil.

Speed often forecloses opportunity to consider it all, to be mindful, or to change one’s mind. Slowness offers a more intimate and physical way of seeing. I’ve talked about this at the end of narrow distances, that in a culture and economic system (racial capitalism) where speed and efficiency are valued above all else, I use a 4×5 camera so that we can be deliberate and slow. How “ung gui” / “戇居” (cantonese word meaning foolish, connotation of wasting time, embedded failure) it is to be slow. How radical it is to be slow.

I’m more interested in working slowly, and to convey through the images that sense of slowness and quietude. To quote Tina Campt, from Listening to Images “quiet is not an absence of articulation or utterance. Quiet is a modality that surrounds and infuses sound with impact and affect, which creates the possibility for it to register as meaningful”. (And now, post National Security Law, I think about this quote in a new way.)

Your recent work narrow distances sits at the intersections of the Asian community with the queer community. What drives you to enable these communities—and the different ways in which they can coexist within a single person—to be seen?

I don’t think I’m really enabling or anything of that nature. I try to avoid ways of talking about photography from that kind of position – and avoid terms like “empower” etc.

For me personally, it really was about being seen, and being able to see. It was the simple fact that growing up, we didn’t have images or narratives that reflected or affirmed us. These worlds and communities — an AAPI community, a queer community and how they intersected or could co-existed had seemed so abstract. Of course, these communities are also so multivalent and not at all one thing or monolithic! The Asian community and queer community had seemed disparate, and divergent, when I was young. I wanted to find community, one that was not compartmentalized or mutually exclusive. (Of course, I didn’t have the framework to understand disidentification until much later!) When I couldn’t find these images, I had to make them. I didn’t have a queer blueprint, let alone one that was Asian or Asian American, or one that did not center whiteness.

Here is an anecdote –

New York Chinatown, in the early 2000s, was still homophobic. In my early twenties, I had worked at a bar in Chinatown. There is no other way to describe this, it was a homophobic and hostile workplace, for most part because of the bar’s owner and her friends. That idea of covering, of figuring out when it was safe…. But it was one incident, unrelated to that bar: in the mid aughts, I had been photographing independent shops in Chinatown, ones that were slowly disappearing. I had worked my way into making regular conversation with this one shop owner, an elder. He finally said yes to me photographing his space, but in a passing comment about my groceries, and cooking, we realized there had been a misunderstanding. My queerness and androgyny were read differently by him; and he had misgendered me this whole time, thinking I was a young man. When I told him who I was, his expression changed instantly, and he turned his back on me. The banter, the project, was over. I remember returning the following week, thinking, if I showed up enough, maybe he would change his mind? (It was a similar thing that was ongoing with my parents, this waiting.) But it was over. It was so finite, that it broke the way I thought about the project and about photographing in Chinatown. (Was this a kind of home, was this a kind of community, to be shunned this way?) It forced me to be more careful and more intentional about finding a queer Asian family. I’ve told this story before, when I came out to my parents, they had told me that they didn’t know any gay people back home. There are no gay people in Hong Kong! And that I learned this in America. I’ve spent the past 23 years unlearning this harm. In making the photographs that comprise narrow distances, so much of it came from this desire to unlearn the fear, shame, and guilt; to connect these communities and worlds, and as you say it, for it to be embodied in one.

In previous interviews about your portraiture, you have articulated a preference for ‘building’ an image with your subject, rather than ‘capturing’ or ‘shooting’ their likeness. Why is this distinction important to you?

Yes, I’ve talked about this a lot in previous interviews and talks—and it comes from just really struggling with how the history of photography—the whole endeavor really – can be so violent. The terms ‘capture’ and ‘shoot’ are violent; even “taking a photograph” – are so extractive.

I prefer building an image—because that is what we are doing – building an image together, it’s through discussions, and the process is slow and dialogical and collaborative. We’re building an image we want to see, and world-building together.

How do you relate to, and what do you make of, the identifier ‘Asian American’? What influences do you think your Asian American-ness—combined with other facets of your identity—have on your art practice, if any?

Yes I identify as Asian-American. I don’t have a problem with that; and embrace a hyphenated identity. (I’m also schooled in the U.S., a fact that I have to name.) But I would say it’s absolutely intersectional – gender, race and class. I also identify as queer, and as an immigrant. (We are all more than one thing.) I was born in Hong Kong, and identify as part of a diasporic Hong Konger. In my census, I wrote Hong Konger rather than Chinese. I was raised by immigrant parents who held onto a 1970s version of Hong Kong, and a much more insular way of existing; as if stuck in time to preserve a sense of home. My parents had grown up poor, and had not finished high school. My sisters and I were first generation students in college; For me, my class position is also an important facet of my identity – I identify as scrappy, but I also acknowledge that my immigrant working class work ethic really sabotages me (as a worker bee, and at best a termite, either way, invisible).

It’s also worth noting that in the 80s and 90s, assimilation was something that immigrant households aspired towards; and was a means of survival. Now, we have the lens and framework to understand assimilation for what it is: harmful, toxic, and a result of — and arm of white supremacy.

A couple of years ago, some of my work was collected by the Library of Congress. It was a huge moment to be collected and part of this national archive. Mostly it affirmed that the work I had been making — the work I had made in local Chinese restaurants in upstate new York, to the portraits of Asian Americans — are part of American history.

As of late, there has been a marked increase in attention dedicated toward the AAPI community and our myriad experiences. How are you thinking and feeling about this shift in awareness? Does this trend have an impact on how you view yourself and your work?

I have such complicated feelings about this shift in awareness. First, it comes out of the increased violence against our most vulnerable populations: in terms of age (our elders) and class positions (working class, service workers, migrant workers); its linkages to imperialism, a long history of violence and racialized and gendered violence. It took high profile instances of violence against women, and a mass shooting to shift the national awareness and dialogue. Organizers and activists have been talking about this for far too long. The rhetoric of “Chinese flu” “kung flu,” – COVID has brought into sharp relief deep underlying problems of racism and xenophobia and racial capitalism. Of course, we all know that legislation against Asians have been ongoing for centuries and baked into this country, from the Chinese Exclusion Act to the Page Act.

With the attention, they also dare to pit groups against each other – for example the rhetoric of increasing policing, brought up in reaction to the violence against Asians. So all of this frustrating— It’s just so important to make sure it’s not framed as something that is new (people are shocked? Or hearing about this for the first time, or framing it as “ that’s un-american”), trying to make sure there remains an Asian and Black solidarity — and also just trying to make sure that our narratives and stories aren’t centered on our trauma.

Yikes, I am not a fan of the word trend. Identities and lived experiences should not be a trend. Trauma should not be a trend.

Does all of this conscious raising impact how I view myself and my work? Well, I am an artist, advocate, and educator. This is something I’ve done and do — no matter what. I would say in the reckoning, maybe more people have been thinking about what does solidarity mean, especially the history of Asian American and Black solidarity; and thinking about race in the U.S. as beyond a binary. But after all of this consciousness raising, will we remain the perpetual foreigner or perpetual other?

What is something that has brought you joy over the past year?

My wife and I had a baby at the autumn of 2019. Our baby, who is now 18 months old, is what has given me joy this past year. In a year filled with so much pain, loss and isolation, they were the one shimmer of light. How idiosyncratic this person is, so intense and silly. This being makes me laugh and surprises me everyday.

What are you looking forward to?

I haven’t seen art in person since the pandemic; the last shows I saw in person were Alvin Baltrop at the Bronx Museum, and Noah Davis at David Zwirner (and our baby’s first and last shows as well). Now that we’re vaccinated, I’m looking forward to seeing art in person again. I’m looking forward to seeing family and friends this summer. I’m also looking forward to making portraits again this summer!

Related publications:

narrow distances (as of recently, it is sold out on Candor Arts, but people can contact me through my website, I have about 30 – 40 copies and want to find good homes for them)

Best! Letters from Asian Americans in the Arts

Edited by Christopher K. Ho and Daisy Nam

This collection of seventy-three letters written in 2020 captures an unprecedented moment in politics and society through the experiences of Asian-American artists, curators, educators, art historians, editors, writers, and designers. The form of the letter offers readers intimate insights into the complexities of Asian American experiences, moving beyond the model-minority myth. Chronicling everyday lives, dreams, rage, family histories, and cultural politics, these letters ignite new ways of being, and modes of creating, at a moment of racial reckoning.

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

Yorgos Efthymiadis: The James and Audrey Foster Prize 2025 WinnerJanuary 2nd, 2026

-

Time Travelers: Photographs from the Gayle Greenhill Collection at MOMADecember 28th, 2025

-

Jamel Shabazz: Prospect Park: Photographs of a Brooklyn Oasis, 1980 to 2025December 26th, 2025

-

Martin Stranka: All My StrangersDecember 14th, 2025

-

The Family Album of Ralph Eugene Meatyard at the High MuseumDecember 10th, 2025