Andrew Kung

Andrew Kung’s work is a clarion reminder of how imperative it is for historically overlooked communities to be seen on their own terms, and to be met with grace throughout this process of acknowledgement. Building from an acute familiarity with facets of his own Asian American identity, Kung photographs members of the AAPI community-at-large with a knowing tenderness and generosity. The result is a contemporary visual archive that values, cherishes, and gives space to a wealth of diverse and ever-fluid Asian American narratives—an invaluable resource in dismantling stereotypes and generalizations oft-ascribed to these stories. An interview with the artist follows.

Andrew Kung is a photographer based in Brooklyn, NY. His bodies of work, The Mississippi Delta Chinese, The All-American, and To Be Seen, have worked across genres to visualize the Asian American experience. They have been featured in The New York Times, i-D, Dazed, Artsy, and Paper Magazine, with a written op-ed on CNN. Outside of taking images, Andrew is an avid mentor, lecturer, and community builder.

Artist Statement

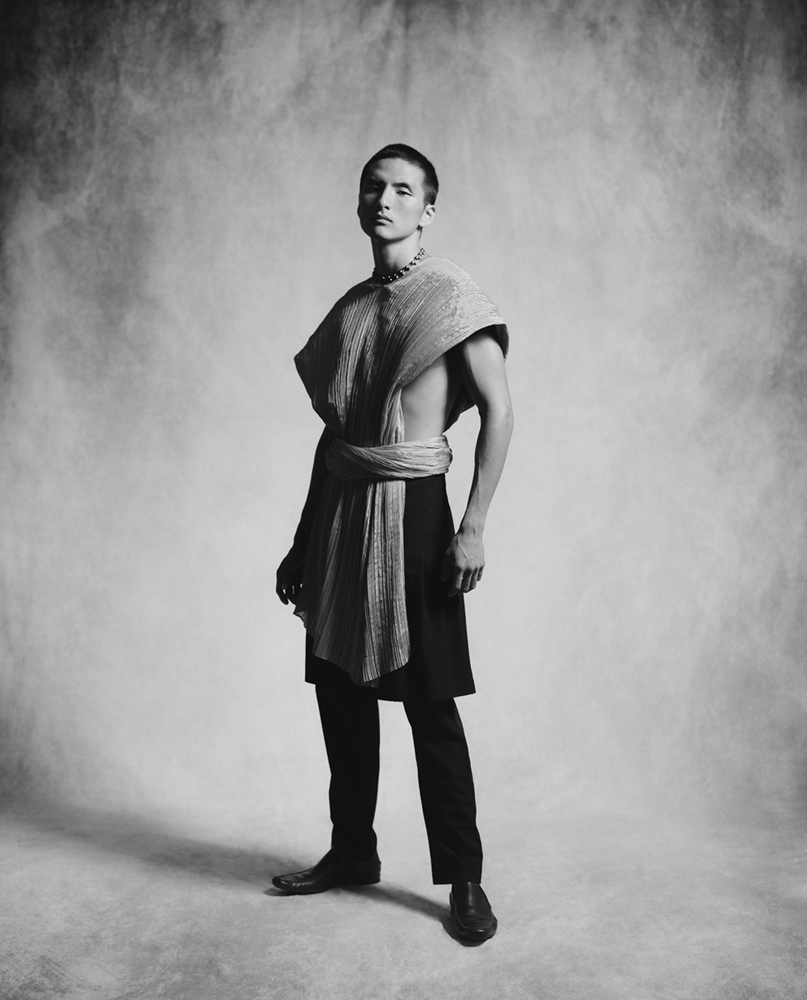

Through my images, my aim is to normalize Asian American beauty, belonging, and individuality. I often investigate themes of masculinity, family, intimacy, and what it means to be American. —Andrew Kung

How and why did you come to photography?

I was exposed to photography in my senior year of college, when I saw beautiful landscape images of San Francisco on Instagram. I went around exploring these new neighborhoods and taking photos on my phone. Having gone to business school and worked in Silicon Valley, I was never exposed to a potential career in the arts because everyone around me was looking at jobs in finance, consulting, accounting, and tech.

It wasn’t until I met a friend/commercial model while working at LinkedIn that I started practicing portraits and asking more questions about what a career in photography looked like. I moved to NYC through my company and shortly quit to pursue photography full time. I wanted to photograph campaigns for brands like Nike and Adidas, and started to cross off a few of these brands from my list in my first year of photography before I realized that I wanted to say something more with my work. That’s when I photographed my first series, The Mississippi Delta Chinese, that documented a small Chinese community with roots in the deep South; little did I know, it began a journey of reclaiming my own Asian American identity. From there, I had more conversations with family and friends about what it meant to be Asian American, read more literature, and watched more cinema – and truly started to find my own voice as an Asian American artist.

Much of your work brings to life the nuances that come with existing as Asian Americans in a country that has not always properly seen and acknowledged our collective presence. How do you relate to, and what do you make of, the identifier ‘Asian American’? How does your connection with Asian America inform your art practice, and vice versa?

To be Asian American is to be East Asian, South Asian, Southeast Asian, among other ethnicities. To be Asian American also spans the spectrum of socioeconomic background, gender expression and sexuality, among other identifiers. Often times, we associate Asian American-ness with a monolithic, heteronormative, binary, East Asian centric point of view. Through my art practice, I’m often portraying the nuance of Asian American-ness through my work, whether it be exploring themes of family, intimacy, masculinity, or what it means to be American – I’m reminded that the beauty of being Asian American is to have a rich, diverse collective of voices that represent our community.

As an artist, part of creating good work is meeting different Asian American communities, starting conversations with people of different backgrounds, and constantly researching the writing of Asian American authors. I want to make sure that I’m being a responsible ambassador in my art practice. And in turn, my art practice helps express these visual narratives back to the community and hopefully contributes to the wider representation of what it means to be Asian American.

Your series The All-American visualizes the intersection of Asian American identity with masculinity—an intersection that, to this day, is filled with misrepresentative stereotypes. What kind of vision of Asian American masculinity do you aim to perpetuate and normalize with your work?

One of the themes I often explore in my work is redefining what masculinity means today. Masculinity has historically been defined by chiseled faces and body types, played by all-American athletes and outgoing personalities; through my work, masculinity is expressed across a spectrum of genders, sexualities, appearances, and ethnicities that haven’t resembled what it means to be “masculine”. Because Asian American men have historically been desexualized as passive, asexual beings – starting from the first Chinese communities that immigrated to the US to the present day portrayals of Asian men in Hollywood and in mainstream media – it’s tempting to portray Asian men through the lens of traditional masculinity. My challenge for viewers is to deconstruct why they’ve viewed masculinity through a singular lens, and to then expose themselves to communities and representations of masculinity that they’ve previously rejected or overlooked.

In recent articles and interviews, you have cited some of the best known fashion photographers—i.e. Irving Penn and Horst P. Horst—as inspirations for your newer portfolio To Be Seen. What takeaways from these photographers have you brought forth into your practice, and how have you made their techniques your own?

Photographers like Irving Penn and Horst P. Horst have shown me how to create drama and narrative in otherwise simplistic aesthetics – they’ve often avoided cluttered environments and set designs, rather focusing more on the human form and the quality/shape of the light. I’ve been exploring how to apply this approach in my own narrative bodies of work and To Be Seen was one of my first attempts after studying photographers like Horst and Penn during the pandemic. In my future works, I’ll be applying their principles of saying more with less, even in images that use environments and set designs.

What is one of your favorite reactions that someone has had to your work?

I don’t think I have one favorite reaction that someone has had to my work, but whenever someone tells me that they feel seen or represented through my work, I’m reminded of my responsibility as an image creator and how it can impact the representations of the Asian American community. I especially love when people share their own personal stories with me because I appreciate their vulnerability and I also get primary research for inspiration in my own work. It’s a great feeling to know that people resonate with the narratives of my images and is an inspiration for me to continue creating and exploring more nuance in my work.

As of late, there has been a marked increase in attention dedicated toward the AAPI community and our myriad experiences. How are you thinking and feeling about this shift in awareness? Does this trend have an impact on how you view yourself and your work?

It’s unfortunate that it took a mass murder in Atlanta for the nation to recognize our collective pain and invisibility as an Asian American community. Since the start of the pandemic, anti-Asian hate crimes have been at an all-time high; news outlets were silent and communities refused to acknowledge the violent hate crimes happening against Asian Americans. Even before the pandemic, anti-Asian hate crime has been normalized, underreported, and otherwise swept under the rug.

The silver lining is that we’re finally finding some momentum and having our voices amplified by those outside of the Asian American community. My hope is that this momentum continues and we’re able to combat larger stereotypes like the model minority myth that discounts any adversity faced by the Asian American community. The journey started a long time ago in dismantling systemic racism, but we still have a long way to go and we all have a responsibility in carrying the torch forward.

What is something that has brought you joy over the past year?

Slowing down. Working on smaller scale projects with my girlfriend/creative partner, renewing my excitement of photography by studying older photographers, watching a range of new films, and not feeling a need to constantly be shooting. By relieving some of the pressure I put on myself to constantly create new work, I’m able to take in new inspiration and find new ways to visually express the narratives I want to explore.

I’m also excited to have seen all of the success and momentum of Asian Americans in Hollywood and in mainstream media this past year; it almost feels like this type of success carries over to the success of Asian Americans in other fields by normalizing the visibility and presence of Asian faces and bodies in spaces and institutions previously off limits.

What are you looking forward to?

I’m looking forward to seeing not only more Asian American representation across all artistic mediums, but I’m also excited to see many new voices and narratives of BIPOC artists – specifically photographers. Institutions like fashion editorials are slowly highlighting a new generation of voices, so I hope that this new wave of momentum will continue for generations to come, as the telling of these stories is an act of justice in itself. My hope is that this will be normalized for all BIPOC artists and that we won’t be viewed as a checkbox for diversity. There’s a long way to go, but we’re taking the right steps forward.

Website: apkung.com

Instagram: @andrew_kung

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

Earth Month Photographers on Photographers: Tyler Green in Conversation with Megan JacobsApril 15th, 2024

-

Luther Price: New Utopia and Light Fracture Presented by VSW PressApril 7th, 2024

-

Emilio Rojas: On Gloria Anzaldúa’s Borderlands: The New MestizaMarch 30th, 2024

-

Artists of Türkiye: Cansu YildiranMarch 29th, 2024

-

Artists of Türkiye: Sirkhane DarkroomMarch 26th, 2024