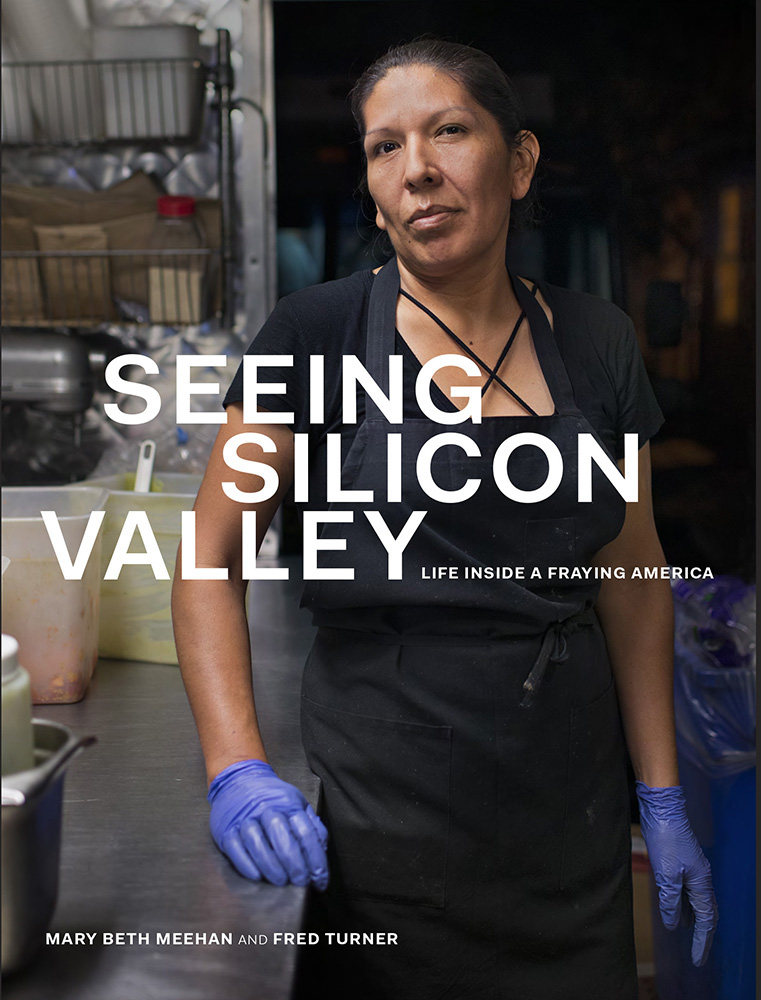

Mary Beth Meehan: Seeing Silicon Valley

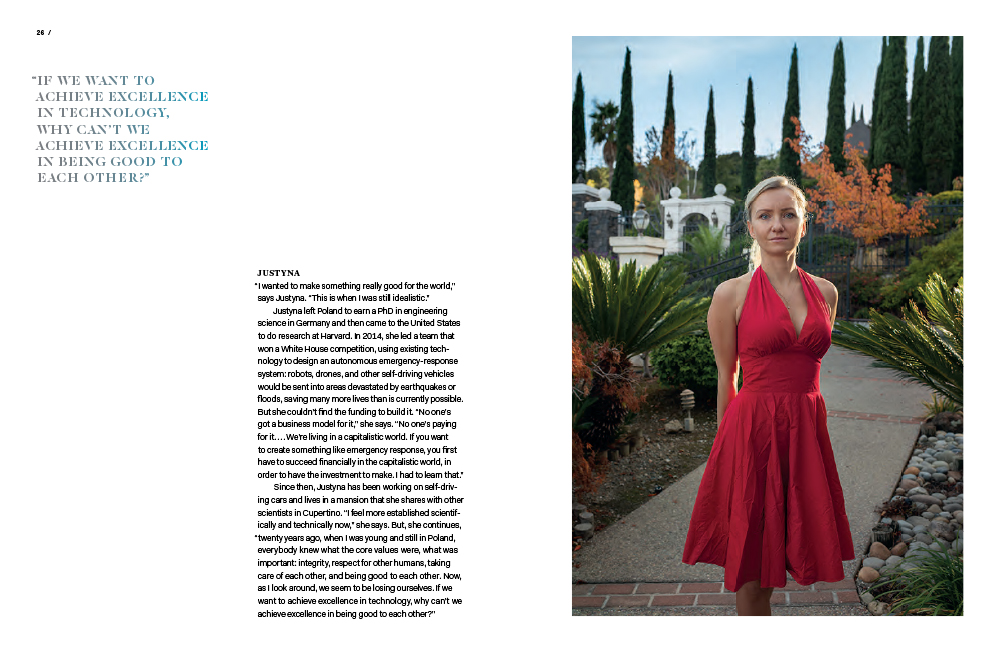

Spread from “Seeing Silicon Valley: Life Inside a Fraying America” University of Chicago Press, 2021

Mary Beth Meehan uses photography to transform public spaces, works collaboratively to reflect communities back to themselves, and aims to jolt people into considering one another anew. Combining image, text, and large-scale public installation, Meehan’s work challenges notions of representation, visibility, and equity, and prompts people to talk with one another about what they see.

Meehan’s first book, Seeing Silicon Valley: Life inside a Fraying America, with Fred Turner, is forthcoming from the University of Chicago Press in Spring of 2021.

“Seeing Newnan,” Meehan’s most recent public installation, was featured on the Sunday front page of The New York Times on Martin Luther King Jr. weekend, in January of 2020, and has shifted the dialogue about representation, identity, and race in that small Georgia city.

Meehan has held residencies at Stanford University, the University of Missouri School of Journalism, and at Brown University upcoming in 2021. She has lectured and led workshops at the School of Visual Arts, New York, the Rhode Island School of Design, and the Massachusetts College of Art and Design.

A native of Brockton, Massachusetts, Mary Beth holds degrees from Amherst College and the University of Missouri, Columbia. She lives in Providence, Rhode Island.

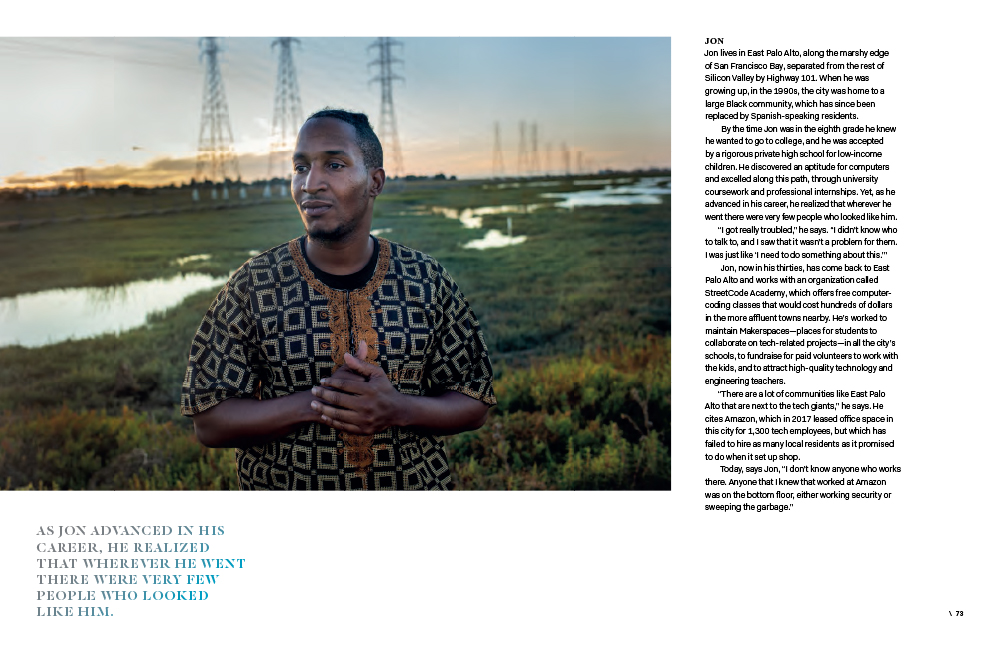

Spread from “Seeing Silicon Valley: Life Inside a Fraying America” University of Chicago Press, 2021

Seeing Silicon Valley

Seeing Silicon Valley is a collaboration between myself and Silicon Valley culture scholar Fred Turner. During the Fall of 2017 I was invited by Turner to hold an artist’s residency at Stanford University, in order to try to see, through my own eyes, what life was like for the thousands of workers in that mythic place. Since then Turner and I have worked together to present what we found – a place, within one of the richest economies in the world, where life is tenuous and where people struggle to find stability, connection, and community. These portraits and narratives are meant to draw viewers in to considering Silicon Valley on an intimate, human scale, and reflecting on what it means for our future.

©Mary Beth Meehan, ABRAHAM and BRENDA Abraham and Brenda have been married for twenty-eight years. Abraham made a solid living as a tile setter, but they lost their house after the crash of 2008. They lived for a time in improvised shacks that friends had set up in their backyards, which are common but illegal and unsafe. Twice the police ordered the dwellings demolished, and each time Abraham and Brenda had to move. So they finally took their savings and bought a trailer, and now they live in a long row of trailers in Palo Alto, parked in front of the Stanford campus. This usually works out okay, but there are times — like on the day of a big foot-ball game — when the university demands that the trailers clear out. On those days, Abraham and Brenda drive over the hills to Half Moon Bay and look out at the sea, From “Seeing Silicon Valley: Life Inside a Fraying America” University of Chicago Press, 2021

©Mary Beth Meehan, CRISTOBAL Cristobal is a United States Army veteran. He served for seven years, including three years in the war in Iraq. He now works full-time as a contract security officer at Facebook. Beginning at sunrise, Cristobal stands at a crosswalk on Hacker Way, guiding the traffic — employee buses arriving, executives in company cars, pedestrians looking down at their phones who need to cross safely. He earns $21 per hour, which doesn’t afford him a home in Silicon Valley. So he lives in a shed in a backyard in Mountain View. Cristobal has spent a lot of time thinking about his time in the army, about how he fought to defend the freedoms that allow a company like Facebook to flourish in this country. He has begun to organize with other service employees in the tech industry — cooks, custodians, security officers — to fight for better benefits, higher pay. He sees himself as part of an army of workers who are doing their best to support the big tech companies. But he doesn’t see any of the wealth trickling down to them. From “Seeing Silicon Valley: Life Inside a Fraying America” University of Chicago Press, 2021

©Mary Beth Meehan, IMELDA Imelda works for a cleaning service. In the early morning, six days a week, she gets picked up by a coworker who drives her to Atherton, one of the wealthiest towns in America. To reach the houses she cleans, she often passes through huge metal gates, up driveways flanked by fruit trees and security cameras. There have been days, she says, when she’s worked in eight of them. A recent pay stub logs her hours, including overtime, amounting to $1,122 for two weeks’ work. With housing prices what they are, Imelda lives in a trailer in a friend’s driveway. She has no utilities in the trailer, so she goes in and out of her friend’s cottage to use the bathroom and kitchen — which are crowded, because there are three generations living there. In Imelda’s sink sits a strainer of persimmons and guavas, gifts from the people whose houses she’s cleaned. From “Seeing Silicon Valley: Life Inside a Fraying America” University of Chicago Press, 2021

©Mary Beth Meehan, KONSTANCE As a teacher, Konstance is one of the thousands of public servants in Silicon Valley who can’t afford to live in the places they serve. For years she joined the commut-ing firefighters, police, and nurses sitting for hours in traffic on the freeways around San Francisco Bay. The situation “really pushes away the people who would make the most impact,” says Konstance. “We could be more effective if we lived a little closer, plus it would feel more like a community.” In July 2017, Konstance won a place in a lottery run by Facebook. It offered apartments to twenty-two teachers in the school district adjacent to the company’s Menlo Park headquarters. The teachers would pay 30 percent of their salaries for rent; Facebook would make up the difference. So Konstance and her two daughters moved to within walking distance of the family’s school. Suddenly, she was surrounded by something she’d been missing: time.Time to make hot meals at home rather than eat in the car, time for her daughter to join the Girl Scouts. Time for Konstance to pursue her own studies and still get to bed at a reasonable hour. But she didn’t feel secure. The program was a pilot, intended to last for only five years. By 2019 she was anxious about whether she’d have to move again, and how she’d come up with first and last month’s rent. Then, in the fall of 2019, Facebook announced a one- billion-dollar commitment to creating affordable housing in the area. Twenty-five million of Facebook’s gift would go toward building housing: 120 apartments, including for Konstance and the other teachers in the original pilot, for as long as they were working in area schools. Konstance expects to receive one of the new apartments, but she can’t be sure. What she’s learned about the program comes from the newspaper and the local grapevine. She still hasn’t heard directly from Facebook. From “Seeing Silicon Valley: Life Inside a Fraying America” University of Chicago Press, 2021

©Mary Beth Meehan, MARK It was the 1970s, and Mark’s mother was working in an electronics plant in Mountain View. Yvette made the lasers that scan groceries in a supermarket and earned $2.70 an hour. She had to heat a green powder with a blowtorch and fuse two pieces of glass together. Every evening, when Yvette got home from work, green gunk would be all over her face and in her nose. Newly married, Yvette became pregnant. One day at work she began to have cramps and went to the bathroom. She had a miscarriage. A few years later, Yvette’s son, Mark, was born. The baby’s eyes were crossed, his hips were dislo-cated, and he had severe brain damage. Doctors told Yvette that he would never talk, never interact with others. Mark didn’t crawl when he was supposed to, didn’t walk. He required constant care. Years later, Yvette heard an ad on the radio from a law firm asking women if they had worked in the electronics industry and if they had a child with symptoms that sounded like Mark’s. She called the law firm. Yvette learned that the green mixture that she had been handling and inhaling was over 60 percent lead, a substance known since the time of the ancient Romans to cause miscarriages and birth defects. Today, the electronics that are designed in Silicon Valley are manufactured in other countries, often in Asia, and many with few regulations to protect workers from toxic chemicals. Mark is thirty-nine now. He still requires constant care and can say only one or two words at a time. Not being able to express himself frustrates him, and he once broke his hand by slamming it against a wall. He loves to play with his stuffed animals and to eat at Chuck E. Cheese. He loves to sing along with his karaoke machine, with its pink and red lights swirling all around him. From “Seeing Silicon Valley: Life Inside a Fraying America” University of Chicago Press, 2021

©Mary Beth Meehan, MELISSA and STEVE After their nineteen-year-old daughter Stevie died by suicide in 2006, Melissa and Steve sought comfort by trying to help others. As volunteers with Kara, a grief support agency in Palo Alto, they’ve spent the past decade counseling parents of children as young as twelve who have taken their lives. When clusters of teen suicides emerged at two local high schools in 2009 and 2014, they were on hand to help. “There is the implication of moral bankruptcy in Silicon Valley,” says Steve, “but I don’t think that’s the case. Parents have the best intentions. But they tend to think it’s a competitive world, so ‘I’ve got to teach my child to excel. If they excel, they’ll be able to compete. They’ll be equipped to cope and be happy.’” Steve says that “the common denominator of people that commit suicide in this increasing phenomenon, particularly in the Bay Area, is that they are more sensitive than average.” He and Melissa describe children who take everything to heart, who don’t know yet what they think and feel, who need time and space to process their lives. Instead, these children find themselves falling off the treadmill that the culture has set them on. “Our intelligence has surpassed our ability to express our emotions,” says Melissa. “We don’t learn about our feelings and how to express them. As a matter of fact, what we learn from a very young age is how not to express our feelings—how to keep ’em inside, how to hide ’em, how to get on with it. How to achieve. “It’s hard to believe,” she says, “that we’re human underneath all this stuff that we see on the outside. We think, ‘We’re Silicon Valley: we’re the products of Silicon Valley, or the makers of Silicon Valley.’ And we’re really humans trying to survive under all of the facade that everyone sees.” From “Seeing Silicon Valley: Life Inside a Fraying America” University of Chicago Press, 2021

©Mary Beth Meehan, RAVI and GOUTHAMI Between them, Ravi and Gouthami have multiple degrees — in biotechnology, computer science, chemistry, and statistics. After studying in India and working in Wisconsin and Texas, they have landed here, in the international center of technology, where they work in the pharmaceutical-technology industry. They rent an apartment in Foster City and attend a Hindu temple in Sunnyvale, where immigrants from India have been building a community since the early 1990s. Although the couple have worked hard to get here, and they make good money, they feel that a future in Silicon Valley eludes them — their one-bed-room apartment, for example, costs almost $3,000 a month. They could move somewhere less expensive, but, with the traffic, they’d spend hours each day commuting. They would like to stay, but they don’t feel confident that they can save, invest, start a family. They’re not sure what to do next. From “Seeing Silicon Valley: Life Inside a Fraying America” University of Chicago Press, 2021

©Mary Beth Meehan, RICHARD Richard has spent his entire adult life in the auto industry, loving his work and making good money. In 2010, the year that GM went bankrupt and the plant he worked at in Fremont closed, he was earning $120,000 a year. After Tesla took over the plant, Richard got a job on the manufacturing floor. He was paid $18 an hour, or less than $40,000 a year. Richard started noticing things that didn’t seem right. As a line worker assembling car doors, he was required to work twelve-hour shifts, five or six days a week. Richard had a home, but he noticed young guys “who came in broke, with a bag of clothes” being hired, working the long shifts, sleeping in their cars, showering in the break room, and doing it again the next day. When a friend invited Richard to meet with the United Automobile Workers union, he agreed. Soon after that, when people complained to him about the low pay or long hours, he’d tell them that with the union, they could stand up for themselves. He handed out buttons and T-shirts, told people they had a choice. “We don’t want to break ’em,” he said of the company. “We just want a little larger piece of the pie — so we can have a cooler of beer every now and then, go camping once in a while.” Though he’d never received a negative review, Richard was fired last October, along with more than four hundred other workers. The UAW has filed a complaint, alleging that Tesla fired workers who were trying to unionize. The worst part for Richard, he says, is that he hears the employees are now too scared to talk about the union. He believes that all his hard work has been in vain. From “Seeing Silicon Valley: Life Inside a Fraying America” University of Chicago Press, 2021

©Mary Beth Meehan, TERESA Teresa works full-time in a food truck. She prepares Mexican food geared toward a Silicon Valley clientele: hand-milled corn tortillas, vegan tamales, organic Swiss chard burritos. The truck travels up and down the valley, serving employees at Tesla headquarters, students at Stanford, shoppers at the Whole Foods in Cupertino. Teresa comes from Mexico. She lives in an apartment in Redwood City with her four daughters. On the door is a drawing in crayon that announces, “Bienvenidos Abuelos: Welcome, Grandparents.” In the last few weeks, Teresa’s parents have been visiting from Mexico. She hadn’t seen them since she was a teenager, twenty-two years ago. “Es muy dificil para uno,” she says. “It’s really hard.” From “Seeing Silicon Valley: Life Inside a Fraying America” University of Chicago Press, 2021

©Mary Beth Meehan,WARREN In junior high, in Illinois, before he knew anyone else who had a personal computer, Warren got to play Lemonade Stand on his uncle Bob’s Commodore PET. At thirteen, he attended a computer trade show in Chicago: “I didn’t even know what I was looking at,” he says. “But it was cool. It piqued my curiosity profoundly.” In high school, Warren sought out a friend who could teach him all the workings of computers. After he graduated as his school’s valedictorian, Warren went to Stanford to study engineering and business. Then he became a venture capitalist, backing such fledgling firms as Skype, Hotmail, and Tesla (and turning down the founders of Theranos, one of Silicon Valley’s legendary frauds). Ten years ago, he says, “I did a very Silicon Valley thing”: he called a few of his industry pals to launch Thuuz, a service that creates highlights of sporting events in real time. He runs the company out of a bungalow in Palo Alto, adjacent to his house—just a block away from the garage where Hewlett-Packard began. Warren’s company is small, and while he wants it to be successful, he doesn’t strive to make it one of Silicon Valley’s giants. “Many of those companies are huge because they are willing to cross some lines,” he says—ethical, moral lines. “Steve Jobs was irascible,” he says, “Jobs was tough, Jobs was rude.” But, says Warren, thanks to the iPhone, billions of people in India and China now have access to information. “I put Steve Jobs above that line and say, ‘Yeah, he could have been a jerk, but he’s above that line.’” Warren feels differently about Facebook’s Mark Zuckerberg. “He has broken some massive, massive rules,” he says. “He is completely abusing his users.” Facebook has “corrupted our election. They corrupted Brexit, over in Europe. They’ve destroyed minorities in Asia. . . . They are below the line, below the line. Absolutely, below the line.” From “Seeing Silicon Valley: Life Inside a Fraying America” University of Chicago Press, 2021

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

Greg Miller: Morning BusMarch 5th, 2026

-

Binh Danh: Belonging in the National ParkMarch 4th, 2026

-

Tom Zimberoff: The White Fence and more..March 2nd, 2026

-

The 2026 Black and White Portraits Lenscratch ExhibitionMarch 1st, 2026

-

The 2026 Black and White Portraits Lenscratch Exhibition | Part IIMarch 1st, 2026