The 2021Lenscratch Student Prize First Place Winner: Allie Tsubota

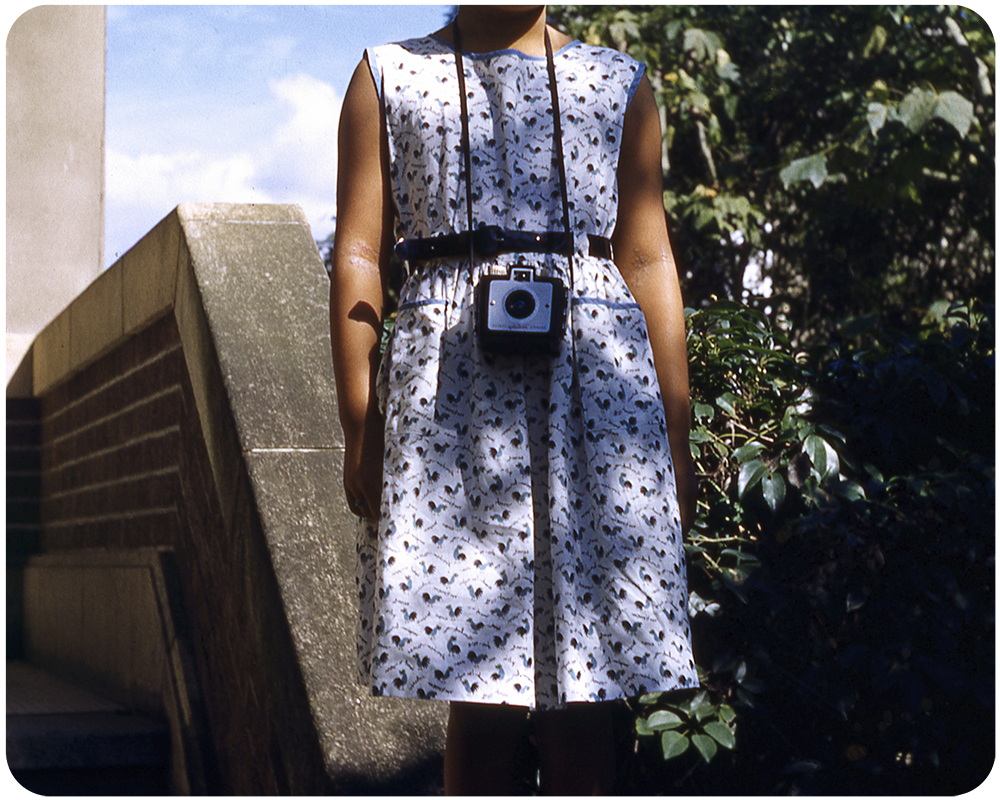

As I aggregate my own family archives–silver prints from the internment camps, Kodachrome slides captured on US military bases, a 1971 Nikomat trafficked from Japan–I feel myself more firmly within this lineage of makers who were both seeing through and seen by the camera, makers who collected visible life while their own racial visibility excluded them from it. – Allie Tsubota

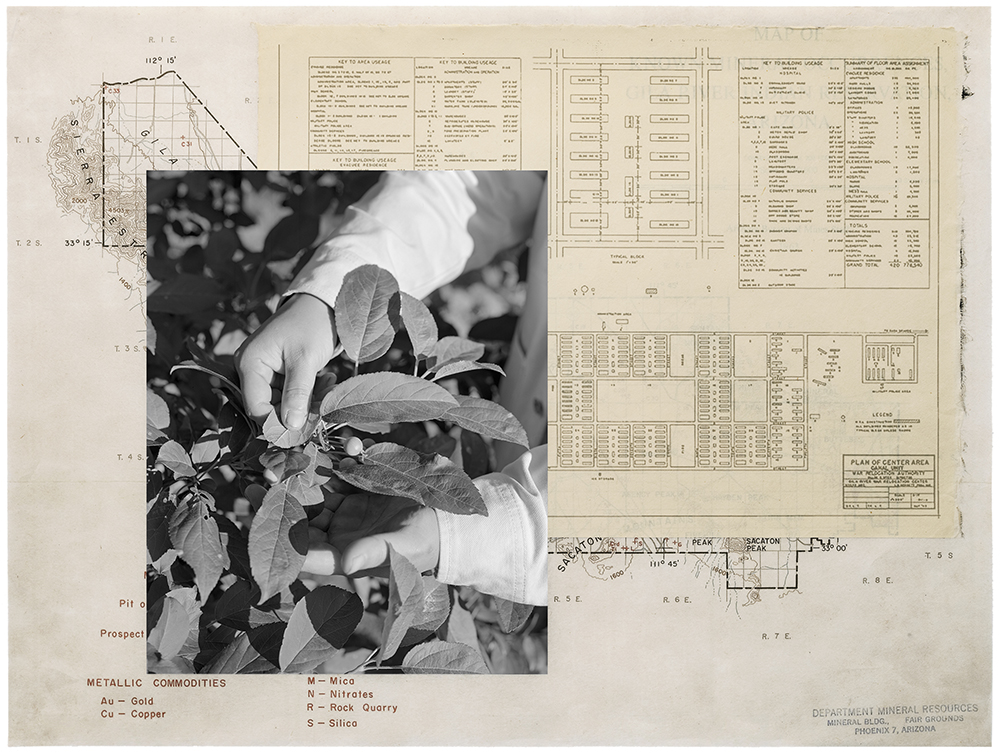

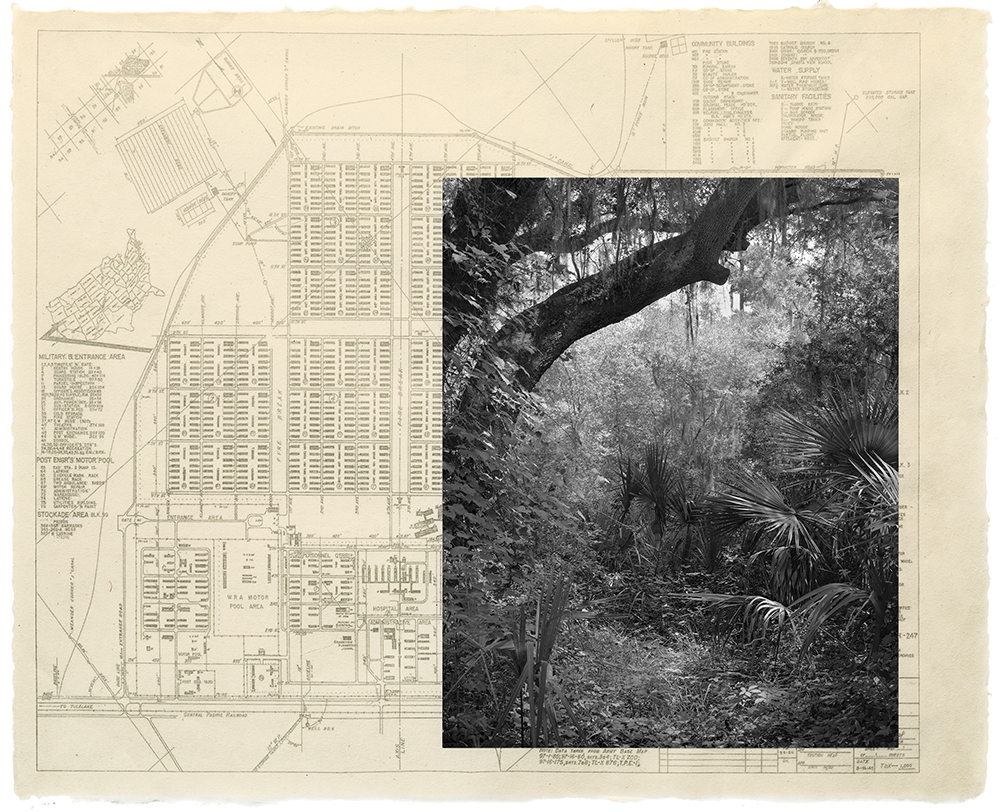

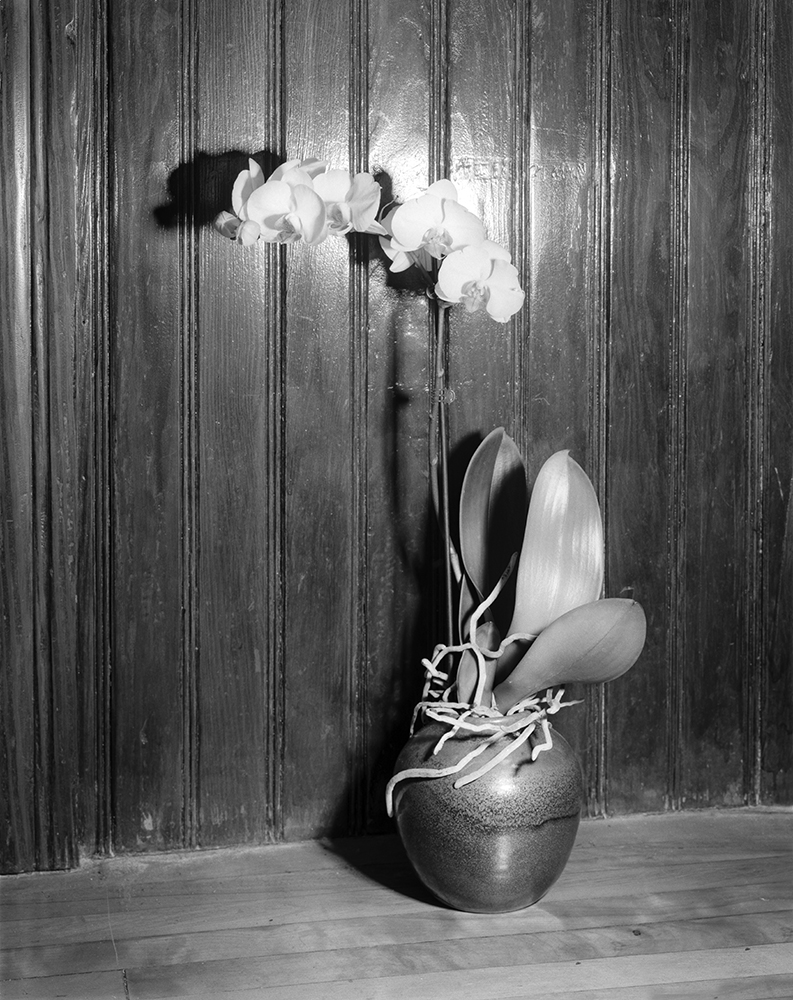

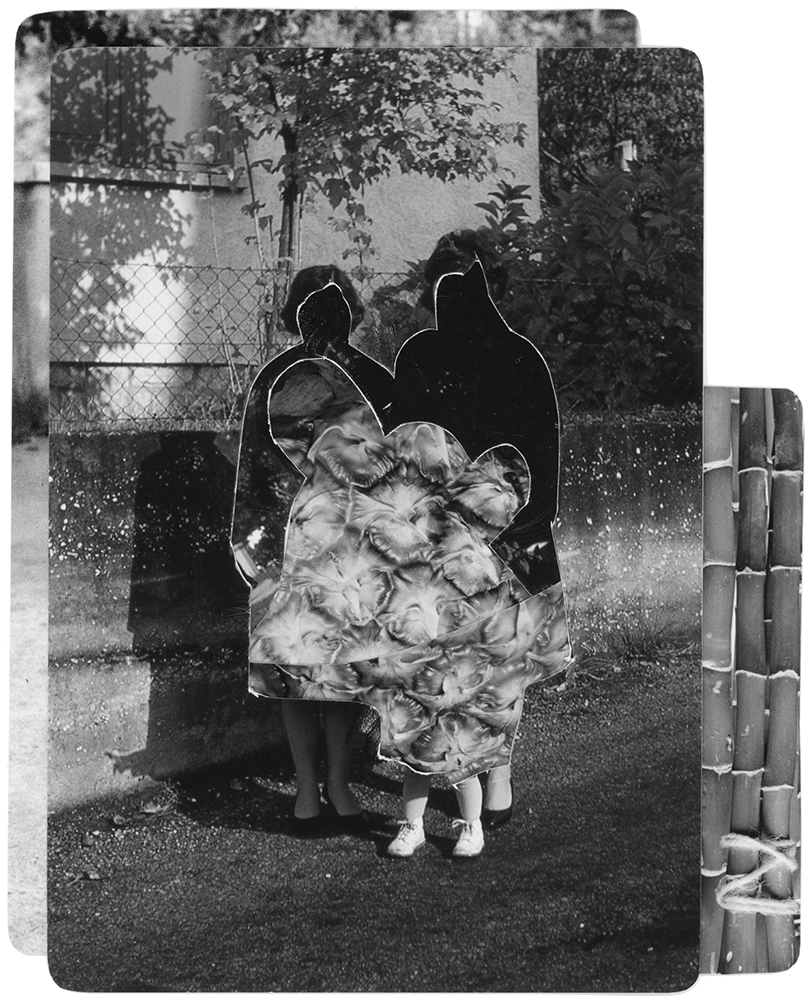

Today, we are thrilled to announce and celebrate the 2021 Lenscratch Student Prize First Place Winner, Allie Tsubota. Allie is pursuing her MFA at the Rhode Island School of Design. Tsubota’s project, This Brilliant Flash of Light, is a potent investigation of the generational trauma and sense of alienation of Asian/Americans across time. Tsubota uses photography as a vehicle to navigate ideas of erased or altered histories. The extinction or suppression of racial histories create, as Tsubota describes, a form of “racial melancholia“, where the eradication of a robust and appreciated self leads to “intergenerational transmutations of trauma, and states of perpetual alienness.” Assembled from a variety of archival and appropriated materials alongside original photographs, this project is a layered study of denigrated histories and how it affects a not only a sense of self , but the loss of cultural and personal identity.

Tsubota will receive: a $1500 Cash Award and a feature on Lenscratch, a FUJIFILM X-E4 Body with XF27mmF2.8 R WR Lens Kit, Silver (MSRP $1,049.95 each), a $250 cash prize from The Griffin Museum of Photography, a $500 Gift Certificate from Freestyle Photo Supplies, a $500 Gift Certificate towards a Los Angeles Center of Photography Workshop, a $1000 Gift Certificate towards a Santa Fe Photo Workshop, a mini exhibition on the Curated Fridge, a collection of books from Yoffy Press, a collection of books from Kris Graves Projects, a year long mentorship with Aline Smithson, and a Lenscratch T-Shirt and tote. So much appreciation to our wonderful sponsors.

An enormous thank you to our jurors: Aline Smithson, Founder and Editor-in-Chief of Lenscratch, Educator and Artist, Daniel George, Submissions Editor of Lenscratch, Educator and Artist, Kellye Eisworth, Managing Editor of Lenscratch, Educator and Artist, Alexa Dilworth, publishing director, senior editor, and awards director at the Center for Documentary Studies (CDS) at Duke University, Kris Graves, Director of Kris Graves Projects, photographer and publisher based in New York and London, Paula Tognarelli, Director of the Griffin Museum of Photography, Hamidah Glasgow, Director of the Center for Fine Art Photography, Fort Collins, CO, Raymond Thompson, Jr., Artist and Educator, winner of the 2020 Lenscratch Student Prize, Guanyu Xu, Artist and Educator, winner of the 2019 Lenscratch Student Prize and Shawn Bush, Artist and Educator, winner of the 2017 Lenscratch Student Prize.

This Brilliant Flash of Light

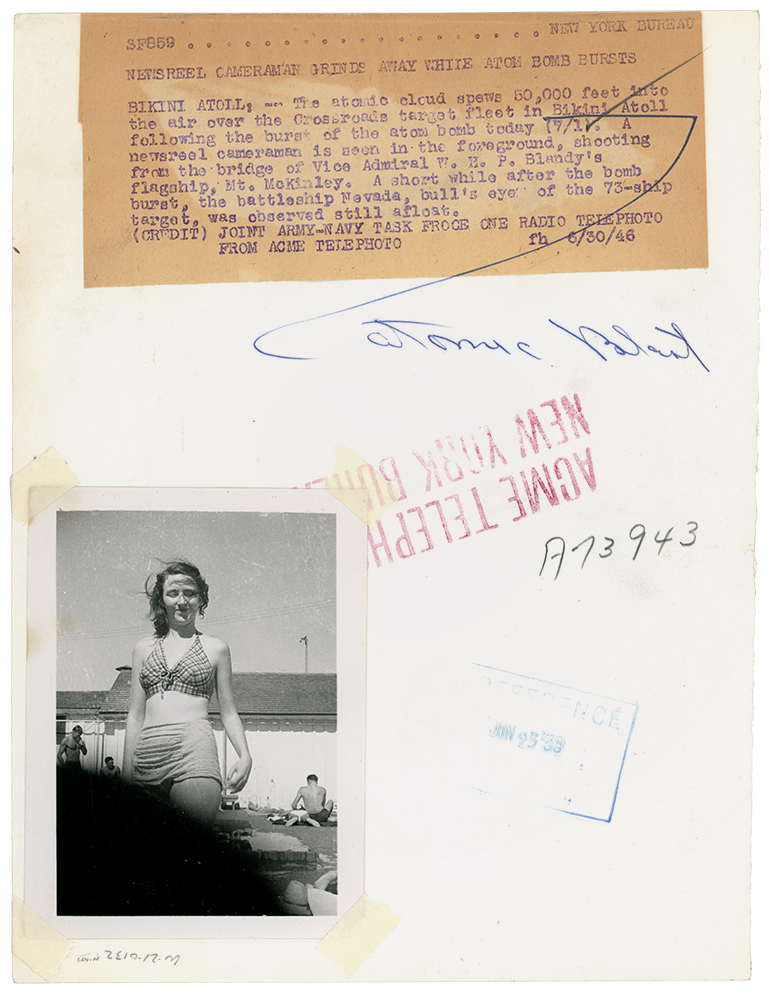

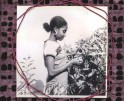

The psychic lives of Asian/Americans are mediated through histories of migration, racialization, and assimilation–three processes that produce what David Eng and Shinhee Han describe as a form of racial melancholia. Racial melancholia is a condition of the assimilated, racialized body–a collective, psychic casualty of histories of settler colonialism, racial capitalism, and white hegemony manifest as a form of self-erasure, or of loss. This work begins to trace this type of melancholia retrospectively through time, from the present myth of the “model minority,” to American militarism and forced assimilation during WWII, to those early Asian migrants coerced into plantation labor in Hawai’i. It reflects my attempts to assemble the psychic landscape of Asian/Americans–one informed by historiographic erasures, collective unrememberings, intergenerational transmutations of trauma, and states of perpetual alienness both connected to and distinct from access to citizenship. Materially, this work is produced from various film types and formats, original and appropriated footage, and archival objects, texts and photographs. It’s guided by scholarship in critical race theory, ethnic studies, and comparative literature, alongside tangential scrutiny of the role of canonical 20th century photographers in reinforcing processes of racialization and assimilation.

Allie Tsubota is a lens-based artist living and working between Providence, RI and central Massachusetts. Her work explores histories of migration, assimilation, and racialization, as well as questions of national belonging and postmemory within Asian Americans and those of the Asian diaspora. She is currently pursuing a Masters of Fine Arts at Rhode Island School of Design.

Tell us about your growing up and what brought you to photography?

What I initially loved about photography was that it took me out into the world. I’d been trained as a dancer through my mid-20s, and so was more accustomed to a studio-based practice where, conventionally, the work is confined to a predetermined space. Photography presented a medium that allowed me to both think deeply and traverse physical space, and so it became my primary mode of moving, of making, and of learning.

What I continue to love about photography is the way it connects me, within my own family, to generations of Japanese Americans fascinated by such technologies of light. I subscribe to Jonathan Crary’s notion of photography as a mode of sociality as well as a technology–that a photograph is a social product as much as it is a material object. As I aggregate my own family archives–silver prints from the internment camps, Kodachrome slides captured on US military bases, a 1971 Nikomat trafficked from Japan–I feel myself more firmly within this lineage of makers who were both seeing through and seen by the camera, makers who collected visible life while their own racial visibility excluded them from it.

Congratulations on your Lenscratch Student Prize! What’s next for you? What are you thinking about and working on?

Thank you! I’m so grateful to Lenscratch, the jurors, and all of the contributors who gave their time and resources to these awards, which truly are unique in terms of the level and diversity of support and opportunity they offer.

In the next few months, I’ll continue to develop work that explores the lives of Asian/Americans as landscapes characterized by histories of migration, racialization, and assimilation–three processes that produce a sort of collective and pathological “racial melancholia.” This is a project that looks to the historical and to the archive–or to the dearth of the archive–collecting bodies of knowledge that remain marginalized or subordinated and reflecting on how they continue to exist in the lives of Asian/Americans today. I’m looking to the present myth of the “model minority,” American militarism and atomic warfare across the Pacific, forced assimilation during WWII, and 19th century migrant labor as historical anchors that map alongside broader structures of state-sanctioned settler colonialism, racial capitalism, and white hegemony. Photography is very much my way of learning, and so the work has been as much about recovering repressed or denigrated histories as it has been about making photographs.

We’re always considering what the next generation of photographers is thinking about in terms of their careers after graduation. Tell us what the photo world looks like from your perspective; what do you need in terms of support? How do you plan to make your mark? Have you discovered any new and innovative ways to present yourself as an artist or connect with others?

As a graduate student, my purview is mostly on institutions of higher education, and so I’ll share a few reflections in that realm:

“Decolonizing” institutions: We’re all witnessing calls around the country for institutions to address their complicity in upholding structures of racism (and if you really want my uncensored take, structures of American empire) inseparable from structures of settler colonialism, indigenous dispossession, and white hegemony. These efforts–these changes–are so sorely needed, but the lack of sincere institutional investment in them results in such efforts remaining largely performative. We need institutions to properly allocate funds toward opportunities for artists and educators of marginalized communities/identity, funds that reflect competitive salaries for new hires and monetary compensation for existing faculty serving on DEI or race and decoloniality committees. Too often, the burden of transformation is shouldered by the very people it affects most, and so they–and their students–absorb the greatest externalities and suffer the greatest losses.

Arts curriculum: My hope is that arts education begins to universally move beyond the traditional canon of makers and movements–that our photographic curriculum becomes as inclusive and comprehensive as it will be thought-provoking. I would love to see photo history classes that acknowledge the many ways photography and visual culture have reinforced processes of oppression and racial violence–early photography as a manufacturer and distributor of taxonomical racial difference, a genealogy of 20th century landscape photography that includes Manifest Destiny and notions of racial purity, the high-speed camera as indispensable in the development of the atomic bomb, and so on. Photographers are cultural producers living within a deeply entangled history, and I would advocate for students of art to have uncensored access to it.

Support: Pursuing an arts education and maintaining a creative practice is financially inaccessible to so many makers, which is why support for students and emerging artists (in the form of scholarships, grants, exhibition opportunities, professional development, and continued learning) is crucial. Submission opportunities with free entry are so important, as are awards that allow artists to share their practice and research through exhibitions, talks, or features (like this one!).

Collectivity: Lastly, in terms of new and innovative ways of working as an artist, I’ve been very fortunate to work alongside fellow makers and friends that continue to support and challenge me. Graduate school has been an extraordinarily difficult and transformative journey, one that would be fundamentally lesser without the presence of a community. Artists work and develop alongside each other. We learn from each others’ experiments, successes, and failures, and my hope is that we continue to collectively share with and celebrate each other. This could be a call for more shared, long-term residencies, artists talks around group exhibitions, or for simple acknowledgements of how the support, research, and labor of others gives life to our own practices.

Are there any instructors or mentors you would like to acknowledge?

My deepest gratitude to Stanley Wolukau-Wanambwa, Alex Strada, and Joon Lee, three invaluable thinkers and makers at Rhode Island School of Design.

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

Lenscratch Student Prize Honorable Mention: Chantal LesleyJuly 22nd, 2021

-

Lenscratch Student Prize Award Honorable Mention: Lois BielefeldJuly 21st, 2021

-

Lenscratch Student Award Honorable Mention: Vanessa LeroyJuly 20th, 2021

-

Lenscratch Student Prize Honorable Mention: Alayna N. PernellJuly 19th, 2021

-

Lenscratch Student Prize Third Place Winner: André Ramos-WoodardJuly 16th, 2021