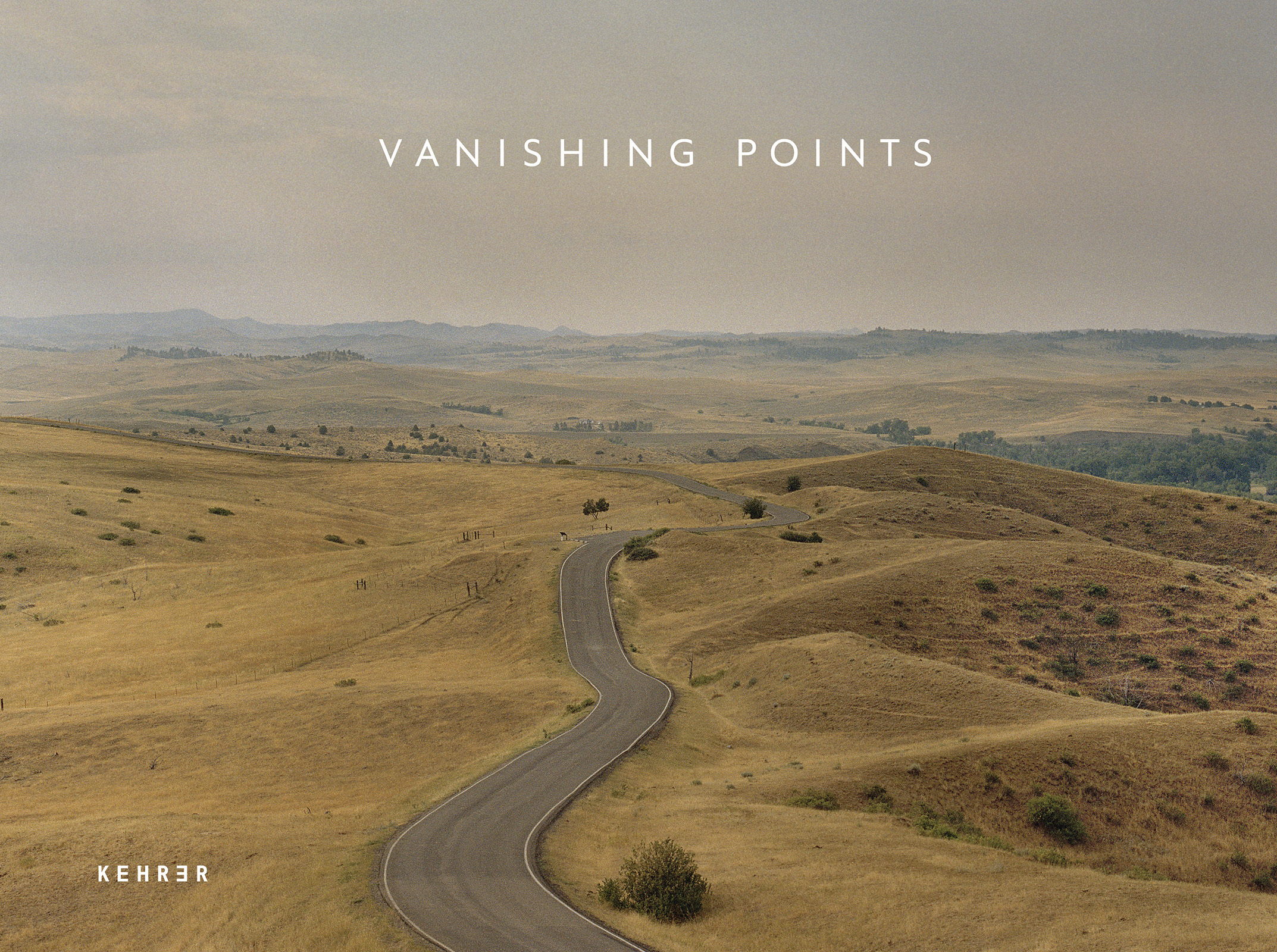

Michael Sherwin: Vanishing Points

Today we are pleased to feature Vanishing Points, by Michael Sherwin. Vanishing Points was recently published by Kehrer Verlag, and is available for purchase in both trade and limited editions. The following conversation between Michael and art historian and curator, Carl Fuldner, took place between July 9th-15th, 2021.

Michael Sherwin is an artist currently based in the Appalachian mountains of northern West Virginia. From an early age he found inspiration in the phenomena of the physical world and has spent most of this life exploring and seeking wild places, including nine years in the American West. Using the mediums of photography, video and installation, his work reflects on the experience of observing nature through the lenses of science and popular culture. He has won numerous grants and awards for his work and has exhibited widely, including recent shows at the Clay Center for Arts and Sciences in Charleston, WV, Huntington Museum of Art in Huntington, WV, Morris Museum of Art in Augusta, GA, CEPA Gallery in Buffalo, NY and the Atlanta Contemporary Arts Center in Atlanta, GA. Reviews and features of his work have been publicized in Art Papers magazine, Oxford American Magazine, Prism magazine, Medium’s Vantage and National Public Radio. He has lectured extensively about his work at numerous universities and conferences across the nation. Sherwin earned an MFA from the University of Oregon in 2004, and a BFA from The Ohio State University in 1999. Currently, he is an Associate Professor of Art in the School of Art and Design at West Virginia University. He is also an active and participating member of the Society for Photographic Education and the lead instructor for WVU’s Jackson Hole Photography Workshop.

Carl Fuldner is Daniel F. and Ada L. Rice Postdoctoral Curatorial Fellow in Photography and Media at the Art Institute of Chicago. He lives in Evanston, IL.

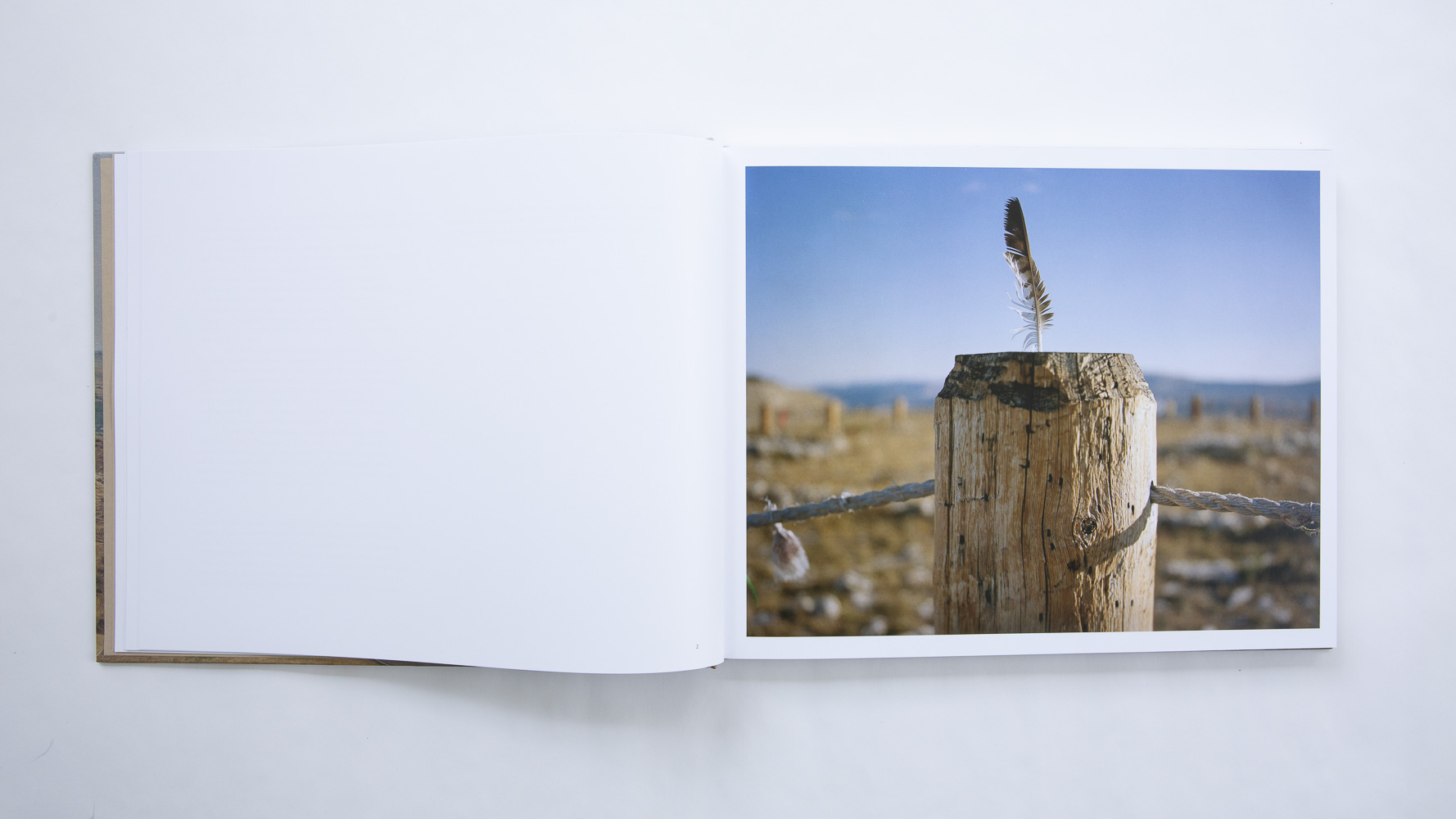

©Michael Sherwin, Eagle Feather, Medicine Wheel National Historic Landmark, Bighorn National Forest, WY

Vanishing Points

My most profound memories and life experiences are associated with the land. As a young boy, I grew up without any spiritual direction. Instead of attending church on Sundays, I was taken on long wandering walks in the hardwood forests of rural Southeastern Ohio. The natural world was my escape, an energetic force that was full of wonder, magic and mystery. These early experiences in nature were formative in my life and spiritual path. They led to considerable time spent in the backcountry exploring my own connection with the earth and a profound respect for the physical world. They have also left me with looming philosophical questions about the tenets of Western religion regarding the sanctity of the land.

In the name of Manifest Destiny, Westerners expanded the reach of settler colonialism across America, claiming the land was theirs by Divine right. Modernization and what settlers’ deemed to be “civilization” swept across the continent “improving” the country and nearly erradicating entire Native cultures in their path. As a white, non-Native citizen of this country, I realize I am complicit in this act of genocide. I grapple with the legacy of my ancestors and my own indirect impact on Indigenous Americans. At the same time, my spiritual views more closely align with those of Native American cultures and Eastern religions. This existential dichotomy of living in America is present in every facet of my life.

Shortly after moving to Morgantown, West Virginia, I discovered that a local shopping center had been built upon a 800-year-old sacred burial ground and village site associated with the Monongahelan culture. I’d frequently shopped at the Center and this new revelation transformed my understanding of the landscape and place I called home. Reflected in the scene in front of me was an ancient, spiritually important and hallowed landscape clouded by the tangible constructions of modern Western culture. In an effort to reckon with this conflict, I was compelled to photograph the site and the resulting image held a mysterious duality. While the photograph is always rooted to the present moment, it can also connect to something ancient, alluding to what has happened. A photograph displays what is there and what is not there – a mirror and a memory.

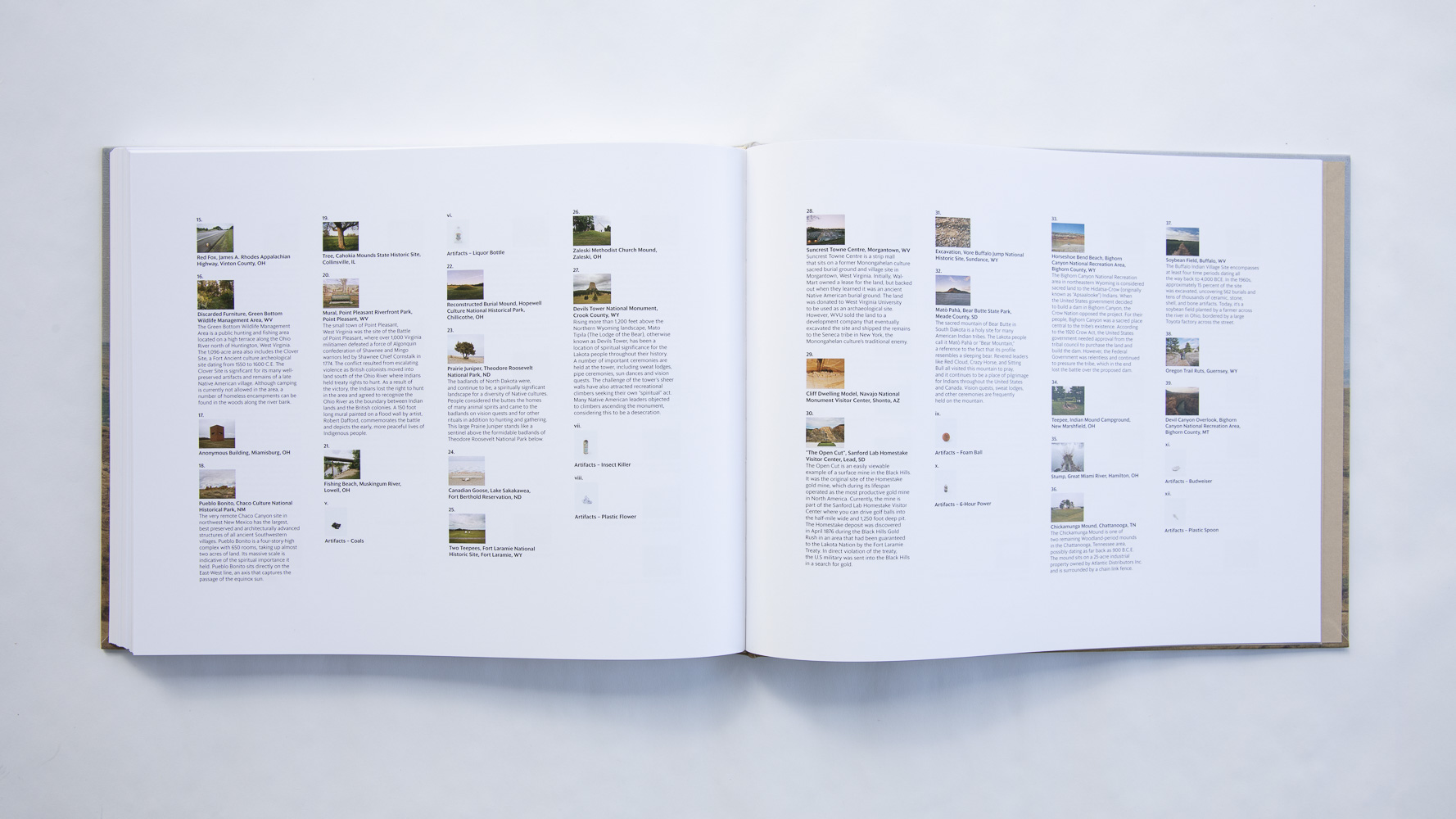

In Vanishing Points, I locate and photograph significant sites of indigenous American presence, including ancient earthworks, sacred landforms, documented archaeological sites and contested battlegrounds. The sites I choose to visit and photograph are literal and metaphorical vanishing points. They are places in the landscape where two lines, or cultures, converge. While visiting these sites, I reflect on the monuments our modern culture will presumably leave behind and what the archaeological evidence of our civilization will reveal about our time on Earth.

Early demonstrations and lingering controversy over the Dakota Access Pipeline project’s harmful impact on the Standing Rock Sioux Tribe’s sacred ancestral land and threat to their water source, have brought new attention to issues regarding the treatment of Native Americans, their lands, and sacred sites. The Vanishing Points project participates in this important conversation, providing a reflection and critique on the historical impacts of Manifest Destiny and the continued subjugation of American Indian tribes, while also connecting a fading past with the familiar present. Part of the allure in visiting these sites is the possibility to experience the land and figuratively reach back in time; to imagine what the land must have been like hundreds and thousands of years ago. I am often reminded of the experiences I had as a child, where the presence of something intangible and much larger than myself still exists.

Carl Fuldner: Hi Michael. I’m back to commuting into Chicago this week for the first time in over fifteen months. I’m realizing how much I missed staring out of a train window to start the day. Also, having just spent some time with your book, I’m noticing all sorts of new details in the landscape! Tell me about Vanishing Points and how it evolved over the eight years you worked on it.

Michael Sherwin: Hi Carl. I love hearing that you have a new awareness of your surroundings after spending time with the work. That’s fascinating and one of the responses I had hoped would happen. The project started back in 2011 when I realized that our local shopping center was being built on an 800 year-old sacred burial ground and village site of the Monongahelan culture. According to reports, it could have been the largest and most important archaeological site east of the Mississippi, yet it was transformed into a familiar and banal setting. I’m really interested in the stories the land holds, both seen and unseen, and in the contrast, or intersection of spiritual beliefs between Indigenous and Colonial, native and non-native traditions.

I began doing a lot of historical research on the Mid-Atlantic and Ohio River Valley region and discovered numerous sites of archaeological importance. It turns out that the area of Southern Ohio where I grew up was an epicenter of the Native world nearly 2,000 years ago, yet I had no knowledge of the land’s previous inhabitants or the spiritual importance of the area. The more I read and researched about the Indigenous history of the United States, the more I wanted to learn, and the more the project grew. It’s been an incredible learning experience!

CF: I lingered for a good while on your image of the shopping mall you mention, the Suncrest Towne Center. It’s a wonderfully rich composition, which channels for me various elements from traditional American landscape painting: the way it captures the quiet of dusk, the slightly ominous cloud form creeping into the upper corner, the tracery of tail lights that suggest time passing. . .the listless American flag at the center—these all feel of-a-piece with Thomas Cole or Frederic Church, who were likewise engaged in developing a grammar for landscape to comment on American settler culture. (The styling of “towne” and the vaguely Federal-style of the mall architecture also feels suggestive given the Colonial frame.)

At the same time, I have a harder time locating vestiges of the pre-Colonial landscape here compared to many of the other images. On the other end of the spectrum, there are equally compelling scenes like the Conus Mound in Marietta, Ohio, where the meeting of traditions spread through time are readily legible. How did that tension, between the “seen and unseen” stories as you put it, shape your approach to the subjects in the book?

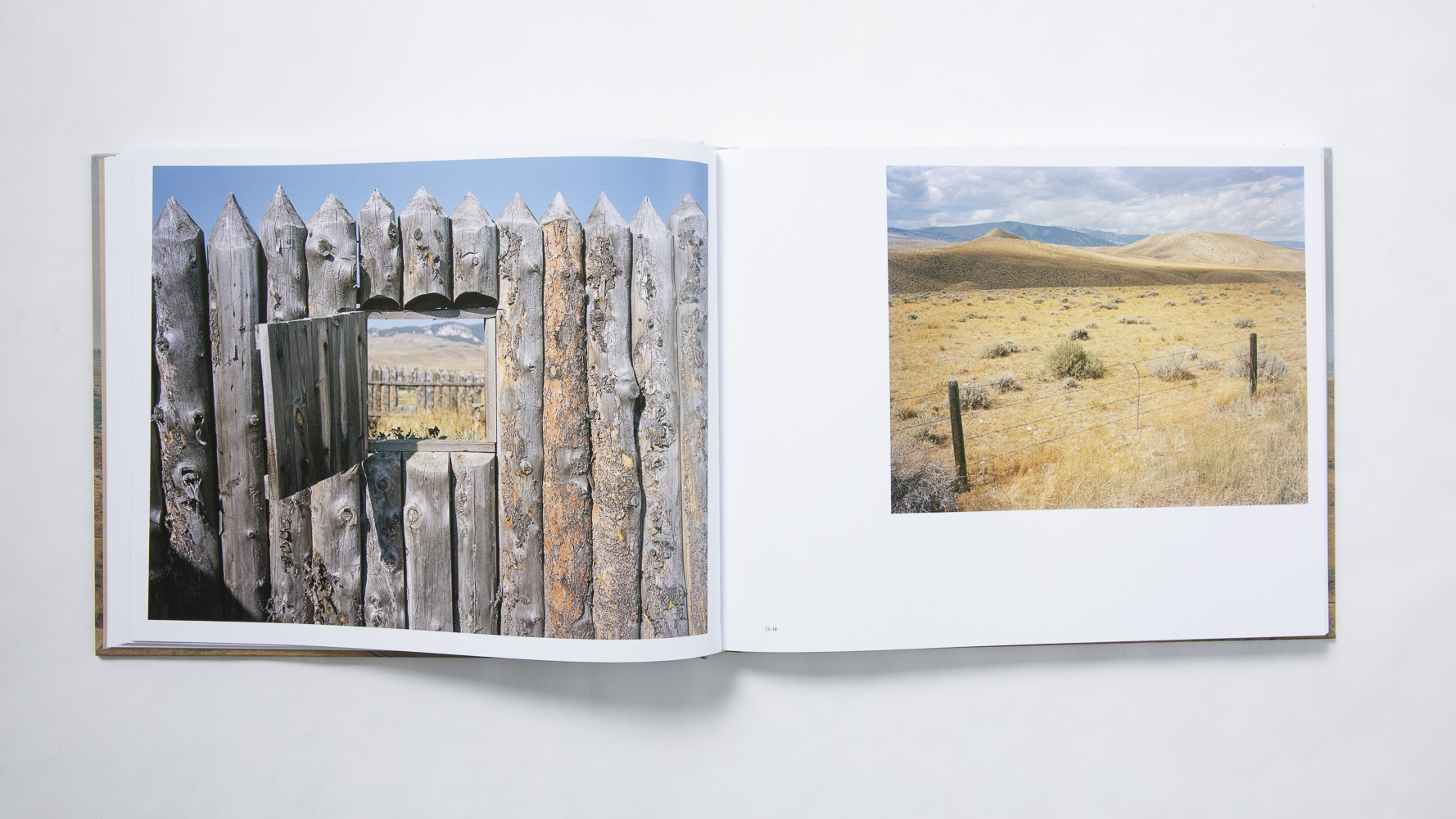

MS: I was definitely thinking a lot about the traditions and tropes of the landscape genre, whether it be painting or photography. I wanted to adopt some of the familiar methods of composition, clarity and seductive color, while also revealing a story or exploring subject matter that is maybe not so pretty. Initially, I think I was subconsciously channeling a lot of the USGS [United States Geological Survey] photographs from the mid to late 19th century. I’ve always been fascinated by those early photographs, which were intended to be more descriptive or scientific than aesthetic or artistic. The irony, I suppose, is that most of the early survey photographs were intentionally devoid of the Indigenous presence to advertise the false notion of a pristine and open frontier.

Many of the sites I was able to identify and visit for the project didn’t have any visual evidence of a cultures’ previous existence. Most of the mounds, earthworks, and/or remnants of dwellings were eradicated either by plowing, development, excavation or simply erosion. As you move through the book, there are images in the sequence of mounds and earthworks that still exist. These few remaining structures remind us that the landscape we are living in was once, and still is, very sacred and important to other cultures. Interestingly, as the project moved west, the sacred and ceremonial forms in the landscape became actual geological landmarks, like Devils Tower, Bear Butte, Shiprock or Canyon de Chelly. These images of familiar physical monuments on the land help connect the ones without any record and hopefully keep you engaged and aware throughout the book. And, as you mentioned earlier, this new awareness hopefully infiltrates your daily life beyond the pages of the book.

CF: Right, yes. Your comment about the USGS photographers is interesting. I hadn’t made the connection, but I am struck by a certain emphasis on linear perspective throughout the book. Many of the compositions feature very exacting spatial geometries, and even some of the more off-kilter images like Stump, Great Miami River leverage perspective to achieve a particular visual effect. I took this to be the more literal (but perhaps less obvious) meaning of “vanishing points.”

Survey photographers like Timothy O’Sullivan used similar strategies to communicate objectivity, casting the landscape as a rational grid. I wonder, at the risk of sounding like an art historian, what function perspective serves in your work?

MS: I think perspective, as a way of looking at things, is always there. There are choices made in the field that are intuitive, unconscious and subjective that naturally inform your perspective. At the time the stump image was made, the project was beginning to grow and I was recognizing that a lot of the images looked alike in terms of compositional arrangement. I wanted to loosen up the series a little and diversify the narrative with varying kinds of images. There were also lots of times when I arrived at a site and the scale of it was just beyond a single image, or there simply wasn’t anything that caught my eye. I spent a lot of time walking around each site, looking at it from different angles, wondering how I might capture it best. Oftentimes, it was a detail in the landscape, rather than the full view that resonated more with me and seemed to illustrate the story of the land in a symbolic or metaphorical way.

CF: Is that how Artifacts came about?

MS: Yes, in a way. I was also thinking a lot about the study of archaeology and material culture, looking at images of ancient artifacts, visiting museums and sifting through archives. One of the very first sites I visited was the Criel Mound in South Charleston, WV, which is surrounded by a busy four-lane road, shops, restaurants and a car dealership. The mound is situated in a small park and when I was walking the grounds I noticed quite a bit of garbage strewn about. Initially, I just started picking up the garbage as an act of respect, and I ended up with a bag full of discarded matter. For one reason or another, I couldn’t throw this stuff away and I ended up collecting more debris at subsequent sites.

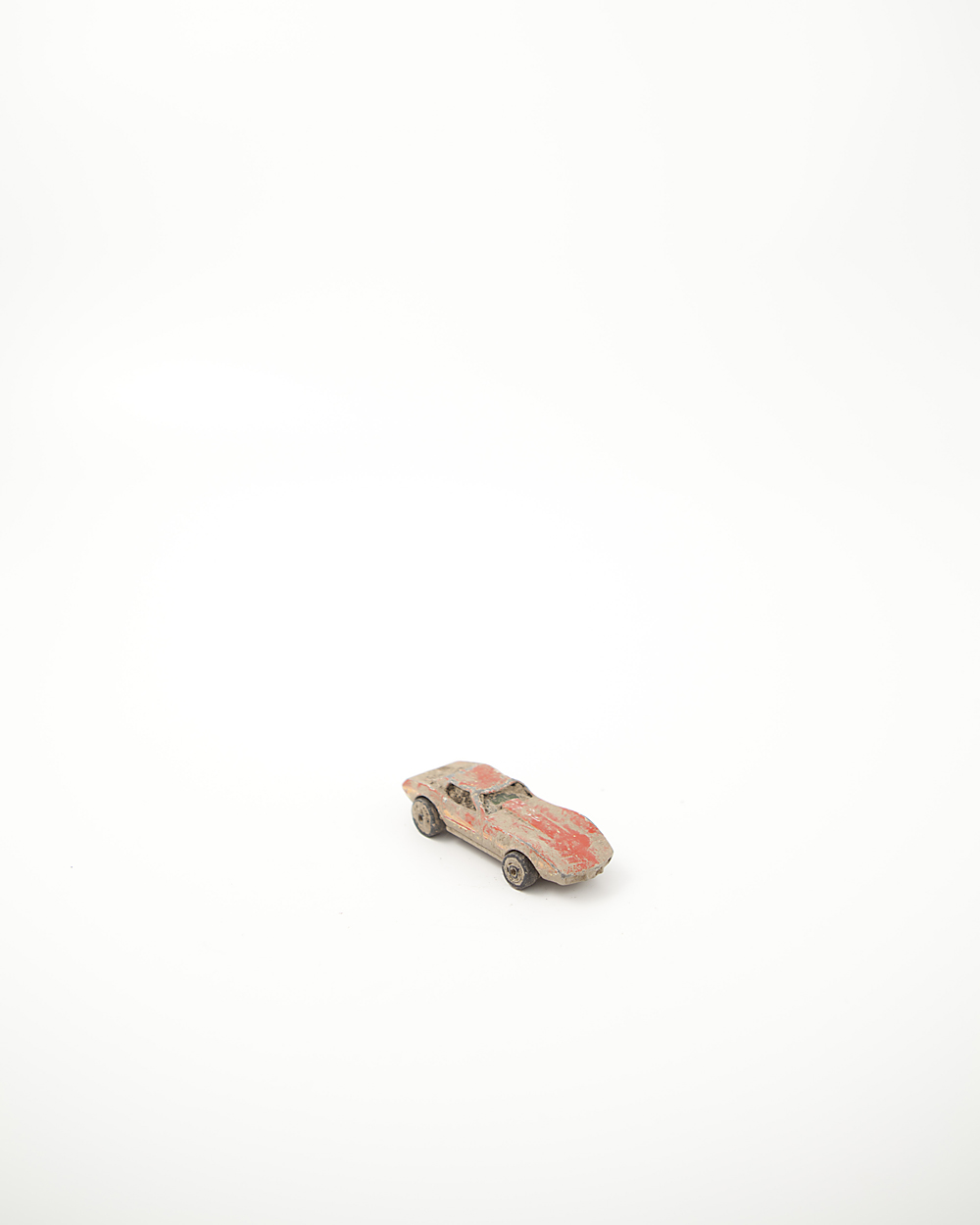

Eventually, I would return home from these expeditions with large bags of trash. I started sifting through them and decided to make individual, quasi-scientific photographs of a selected collection. I was mostly interested in the objects that would still be around hundreds and thousands of years from now. In a similar way that buildings or structures may represent our culture to future civilizations, I was thinking about how these smaller, seemingly mundane discarded objects are also emblematic of our culture. I also really like how the Artifacts series contrasts and compliments the larger, more traditional landscape images, not just visually, but also how they invite a more reflective historical consciousness that spans past, present, and future.

CF: Definitely. They feel in keeping with the survey mode, but there’s also a lightness or even irony in them that adds a layer of self-awareness that carries over into how we view the landscapes. I imagine some future archaeologist tagging and classifying the disposable plastic spoon, speculating about whether it came shrink-wrapped with a knife, fork, and napkin.

This creative blending of past and future points to the more metaphorical meaning of “vanishing points”: a place where the traces of the past converge into the present and disappear from view. There’s a lot at stake in that idea as it relates to Indigenous American culture. Edward Curtis’s iconic work The Vanishing Race from 1904, which shows a group of Navajo riding into the hazy beyond, seems unavoidable. In Curtis’s time, the myth of the “vanishing race” was closely linked to Manifest Destiny, where the disappearance of Native cultures were cast as the inevitable outcome of a natural process, at the same time that the U.S. government was actively, and violently, working to ensure that fate. Do you hope to reframe or reorient that legacy here?

MS: I’m very familiar with Curtis’s work and that iconic photograph. It’s easy for us to look back on Curtis’s work and pass wholesale judgement on his point of view. The hard truth is that Curtis was recording an Indigenous way of life that was quickly disappearing. Certainly there are some issues in how he staged and romanticized his subjects, but that mixed legacy is exactly what has made him such an interesting historical figure for so many.

In my own work, I’m particularly interested in the land as a subject, focusing on specific sites or areas that carry some significant cultural and historical weight. The title, Vanishing Points, is a double entendre, referencing the literal visual aid used to depict depth on a two-dimensional plane, while also suggesting sites in the landscape where the traces of events, or remnants of a previous cultures’ existence has all but faded from view. I’m certainly not trying to suggest that the Indigenous American people have vanished, but I am interested in highlighting how many have been removed from view, especially here in the East,

As a white male with European ancestry, I recognize that I am indirectly responsible for Manifest Destiny and complicit in the genocide and displacement of Indigienous American peoples. At the same time, I grew up without any spiritual direction, eventually finding beliefs in the theories of interconnectivity and the sanctity of the land that are central to traditional Native American belief systems. This existential dichotomy of living in America is present in every facet of my life. With this work, I’m merely trying to reckon with my own physical and spiritual presence on the land, while attempting to unwind/address our collective cultural amnesia. I think there is an ongoing importance to preserving and protecting sacred sites and in some way I hope that my work can help be a conduit for remembrance.

CF: I like that notion of a “conduit for remembrance.” A key distinction seems to be that many of your images, such as the Monongahelan site, relate to cultures that were no longer active even before European contact. In that sense, they belong to a longer past and may not fit as squarely into contemporary discussions around topics like reparations or Indigenous land repatriation. At the same time, as a historian I am acutely aware that what is preserved as a cultural memory, what is deemed worthy of remembering, is structured by historical power relations. Your work not only starts to redress this “cultural amnesia” but also provides a model for a more reflective form of remembrance.

I’m curious about the visual strategies you used to navigate those dynamics. In an interview you gave about this work in 2015, you noted that, as the series progressed, “it became more of a statement and less of a document,” but that you still wished to preserve a neutral stance in terms of your visual approach. The sequencing in the book helps to strike this balance also.

MS: The sequence and layout of images was super important to me and something I spent a lot of time working on. The process revealed elements of the series that I hadn’t really noticed before. There are several single images that I think are strong on their own, but sequencing them with others from different times and locations really strengthened the overall message. I didn’t want them to be grouped by geographical region, date, or any other criteria. I was looking for strands of narratives and formal amalgamations that would tie them together and keep the reader engaged. The designer, Elana Schlenker, introduced two different sizes of images, which I really like and I think it helps break up the sequence a bit. We also wanted to include a lot of open space within the layout to encourage a more contemplative reading, which is more in line with the work. For this reason, you’ll notice that there are very few spreads with two images to negotiate. We also decided to keep the text to a minimum, collecting the expanded information on the sites in an index at the back.

CF: I’m particularly struck by the last few images in the sequence. There’s the image of a hand-painted “Save Our Land” sign on the Pine Ridge Reservation that comes at the every end and works as a coda that places us in the present. The penultimate image in the main sequence, which shows a tree draped in prayer ties on the site of the Wounded Knee Massacre, gestures toward the fraught history of the United States in a more direct way. The image that follows, though—the final image of the main sequence—is much more enigmatic: a lone tree standing at the far end of a clearing that looks overgrown but not entirely wild. Can you tell me about this picture and why you chose to end with it?

MS: Visiting the Pine Ridge reservation and the Wounded Knee Memorial was an incredibly moving experience. Early on in the project, I had an opportunity to research collections at the Smithsonian Institution’s National Museum of the American Indian Archive Center. I stumbled upon an envelope that contained a series of black and white photographs of soldiers standing above mass grave sites containing bodies of Lakota-Sioux, mostly women and children. The conflict at Wounded Knee was originally referred to as a battle, but in reality it was a tragic and avoidable massacre.

The “Save our Land” and Wounded Knee images, which were made on the Pine Ridge Indian Reservation, were an intentional effort to bring the reader closer to the present moment and to illustrate the ongoing battle for justice and recognition that is still happening to this day.

Cleared Meadow is actually one of the earliest images in the series. It was made at sunrise on the Green Bottom Wildlife Management Area, a public hunting and fishing area along the banks of the Ohio River just north of Huntington, WV. The area includes one of the largest Fort Ancient culture archeological sites. I think the image strikes a somewhat hopeful tone with green ferns populating the foreground and the soft pink light of dawn. Throughout the book, subject matter oscillates between ancient sites like this and more recent events or locations. The works speak more broadly about the importance of listening to the land in an effort to better understand the place we call home. The land that we live on was, and still is, sacred. There are still countless stories to be told and lessons to be learned.

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

McCall Hollister in Conversation With Douglas BreaultMarch 6th, 2026

-

Binh Danh: Belonging in the National ParkMarch 4th, 2026

-

Landscape ReEnvisioned Exhibition At the Monterey Museum of ArtFebruary 26th, 2026

-

Olga Fried: Intangible EncountersFebruary 18th, 2026

-

Juliette Ludeker: Somewhere You Can Never GoFebruary 16th, 2026