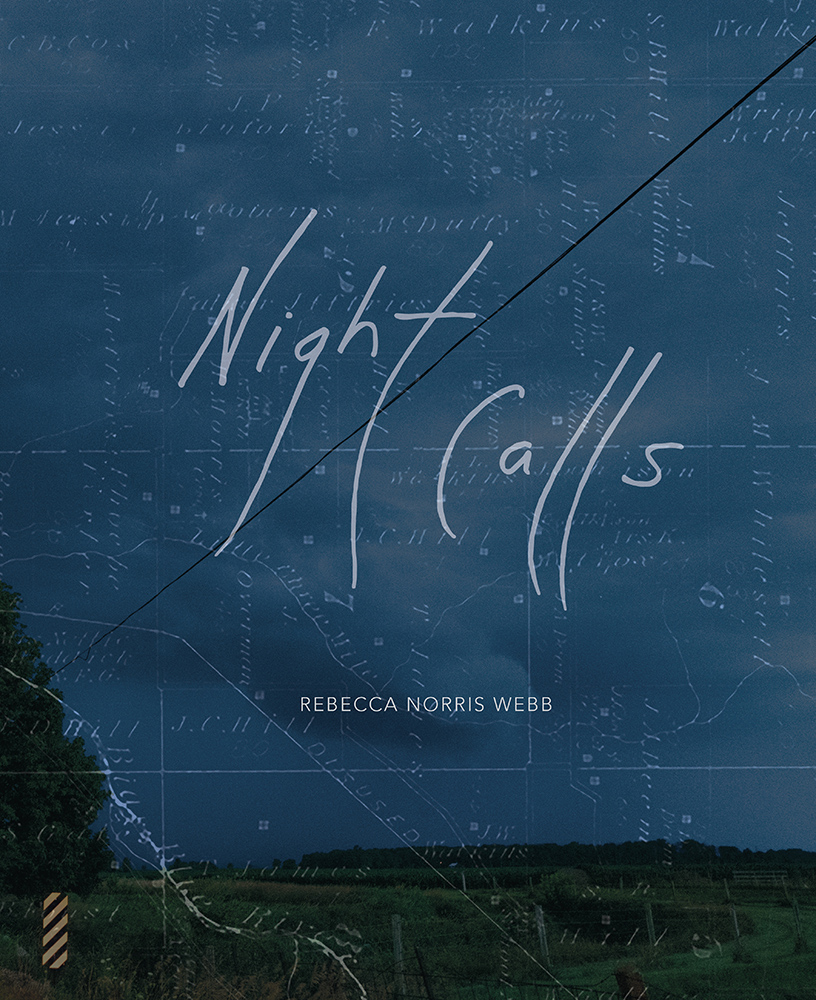

Text + Image: Rebecca Norris Webb: Night Calls

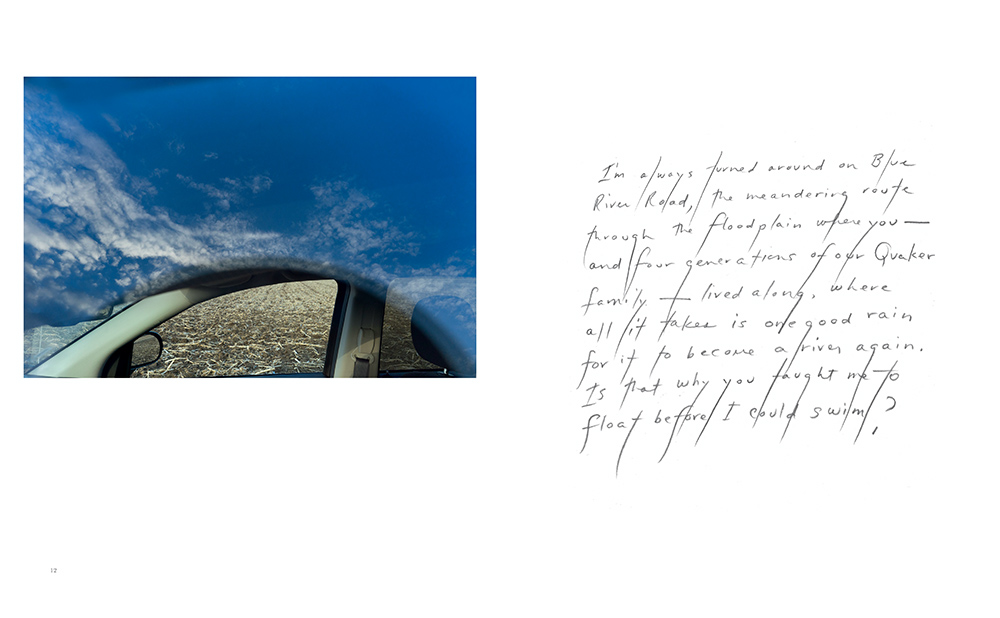

Awash with lush, rich imagery and poetic text, Rebecca Norris Webb’s book Night Calls, published by Radius Books, is a gorgeous homage to her 99-year old physician father and to Rush County, Indiana – the small, rural county where both were born and raised. Photographed mostly at night and in the early morning, Rebecca mirrored her father’s work patterns, as he was often called to patients during the twilight hours. Accompanying her imagery of liminal stillness, landscapes of disorienting beauty and hints of decay, and portraits of former patients are her hand-written musings; bittersweet recollections of history and family ties, and deeper questions she poses directly to her father:

“And when we’re both ghosts? House by house, we’ll watch the porch lights coming on. Won’t the night be a kind of blossoming?”

A meditation on memory, history, family, and the passage of time, Night Calls is a beautiful, melancholy-tinged memoir that expertly weaves text and image together in its emotional evocation of place. An interview with the artist follows.

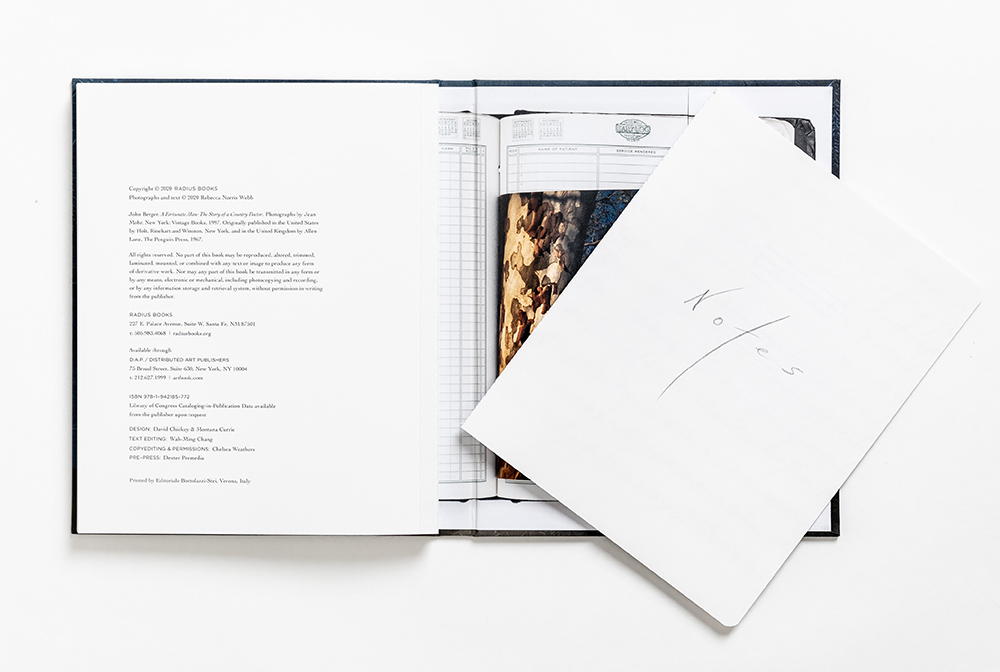

Originally a poet, Rebecca Norris Webb often interweaves her text and photographs in her eight books, most notably with her monograph, My Dakota—an elegy for her brother who died unexpectedly—with a solo exhibition of the work at The Cleveland Museum of Art in 2015. Her work has appeared in The New Yorker, The New York Times Magazine, National Geographic, and is in the collections of the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, Cleveland Museum of Art, and George Eastman Museum, Rochester, NY. An NEA grant recipient, Rebecca’s upcoming collaborative book with Alex Webb, her husband and creative partner, is Waves, will be released in early 2022. IG: @webb_norrisweb @radius.books

Elizabeth Bailey: Congratulations on your beautiful, moving book! What was the genesis of the Night Calls project and how did the book form shape its content?

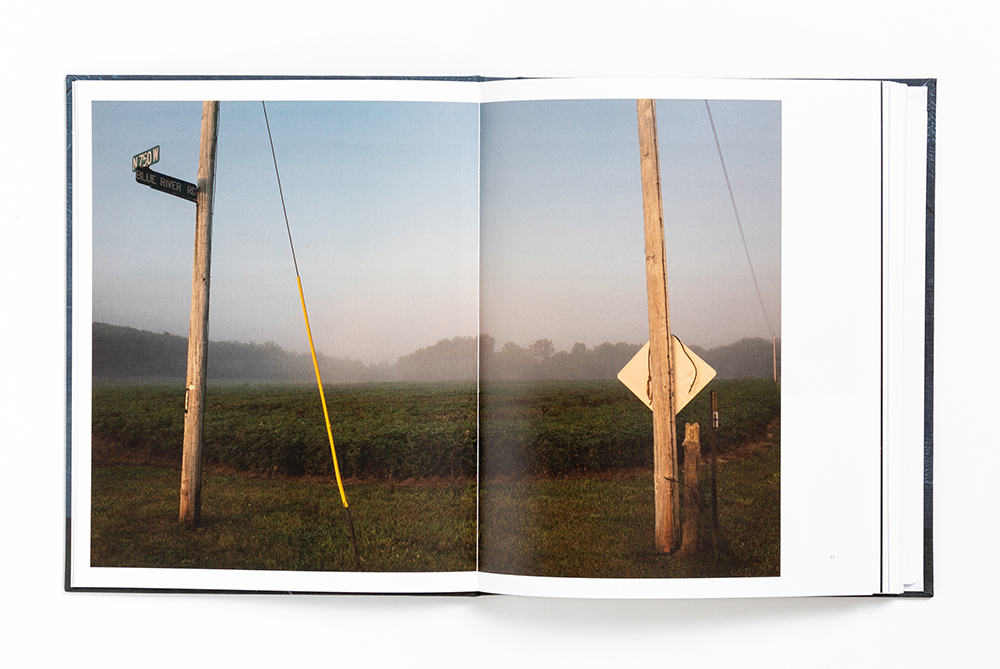

Rebecca Norris Webb: Thanks so much for your kind words about the book. The genesis of Night Calls sprang from a question that arose after I first saw Eugene Smith’s iconic Life Magazine photo essay, “Country Doctor,” while studying photography at the International Center of Photography: How would a woman tell this story, especially if she happened to be the doctor’s daughter? After finishing my second monograph, My Dakota, I finally had the creative space to begin what ultimately became a seven-year creative journey retracing the route of some of my now 101-year-old father’s house calls through the same rural county where we both were born, Rush County, Indiana. The project broke open for me creatively and emotionally when I decided to echo his work rhythms, photographing predominantly at night and in the early morning, when many of us come into the world — my father delivered some thousand babies — and when many of us leave it. Accompanying the photographs are handwritten text pieces, all addressed to my father. Taken together, they create a series of letters to him, told at a slant.

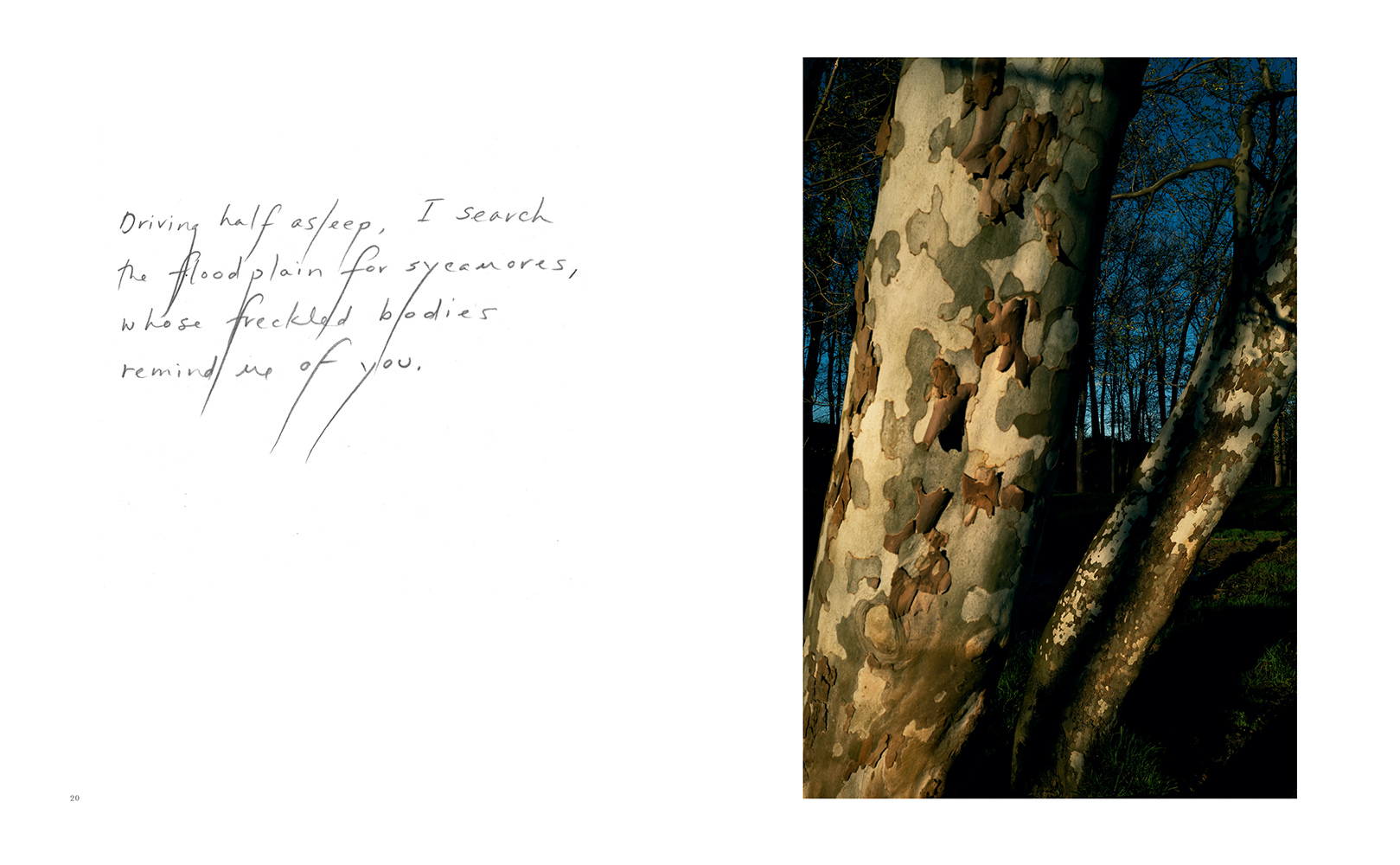

As a bookmaker, I work intuitively to discover the rhythm and sequence of a body of work. About half-way through Night Calls, I made small prints of the images in my studio, working first on a table, then later on one of the magnetic walls of my studio. By listening to how the images — and later texts — spoke to one another, I slowly found the book’s sequence, which fittingly meanders like Big Blue River, which flows alongside the farm where my father grew up and where four generations of our Quaker family lived before him. The sequence of Night Calls meanders from the distant past to the recent past to the present, from early morning to dusk to evening, from fog to thunderstorms to cloudless afternoons. To anchor the book’s meandering sequence, I used four vertical photographs of sycamores, those riparian trees that thrive on the banks of the Big Blue River. Additionally, the sycamores’ mottled bark reminded me of Dad’s freckled skin. So, in essence, this quartet of sycamores became a metaphor for my father.

EB: I’m curious as to how you structured your approach to this project, for example did you create shot lists, or did it gradually evolve and take form? Did it come together differently than you’d imagined?

RNW: Books often surprise one along the way. That’s one of the gifts of being a bookmaker. I often say my images are much wiser than I am. I think I may know where a project is going, but slowly and surely the images show me otherwise.

EB: The poetic text throughout Night Calls tells of family stories and history, of memories in rich detail. Was it always your intention to weave text and imagery together? Is one a response to the other?

RNW: My books — and my way of seeing — are cut from the same creative cloth, which is woven of words and images. After all, doesn’t text come from same root as textile?

EB: Your collaborative portraits have a beautiful stillness, a dreamlike quality to them. Tell me about your process in creating these.

RNW: I’m rather shy, so I saved making most of these collaborative portraits of my father’s former patients until the end of the project. That’s when I stumbled upon my inspiration. I read how August Sander while making portraits of farmers around Cologne, often visited their homes and gardens working “much like a country doctor making house calls.” So I decided to try to channel my father’s gentle bedside manner — a man of few words who listened deeply to his patients — but using my camera in place of his black medical bag. I explained this to his former patients while visiting them in their homes, and asked them to share memories of my father. After listening to their stories, I told them to let their minds wander while I photographed them. Since many of their memories of Dad involved a threshold experience — such as a birth or near death — I often photographed them in a doorway or window. In essence, I see these collaborative portraits as a kind of slantwise portrait of my father.

EB: Your images capture a mood of pensive beauty and melancholy. Have you always felt that in Rush County, or has your perception of home changed over time, of either the place itself or what it means to you? How is this reflected in your work?

RNW: I’ve always felt that Rush County was part of me. Moving away at 15 has given me a different perspective of my birthplace than if I had stayed. I’m not interested in nostalgia — at least not in its oversimplified meaning as a longing for some imagined greatness of the past, or an inability to accept the present. I’m interested in how people and the landscape change over time, and the role memory plays — what we remember and what we forget — and our often subtle emotional response to this. Like the fragile ache that arises while watching people, trees, and buildings slowly vanishing out of sight. I remember coming across a collapsed 19th century barn not far from the farmhouse where my father grew up in Rush County. I was struck by the sheer girth of the beams, cut from beech trees that once towered over the Big Woods, a thousand-acre virgin forest held collectively by the local Quaker farmers in the mid1800’s. I was surprised by the ache that washed through me as I laid my hand on one of these fallen beech beams, whose horizontal fate awaits us all.

Among other things, Night Calls is a meditation on the relationship between memory and one’s first landscape. Many of my earliest and most vibrant memories are entangled in maple or sycamore branches, where I’d spend hours as a child lying on a low limb about four feet above the ground. I remember being mesmerized by the light shimmering through the leaves, while listening to the piercing calls of cardinals and blue jays. Recently, looking at the light falling on a cardinal atop her nest, half-hidden inside a rose bower here on Cape Cod, brought me back to that time, that place. For me, certain kinds of light hold shards of memories, like a kaleidoscope. In a way, I carry Rush County wherever I go.

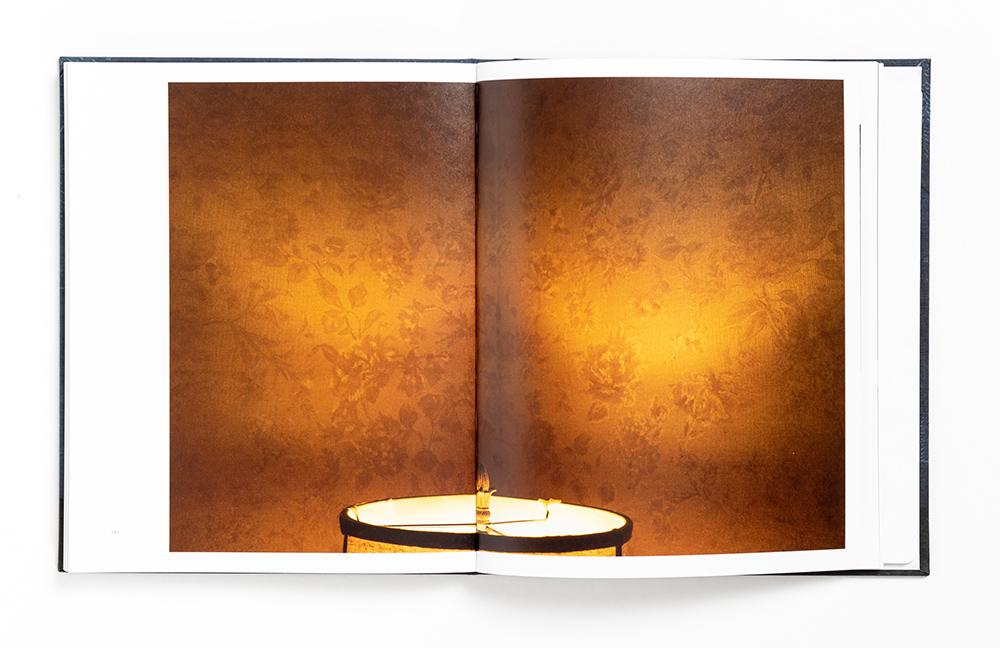

EB: I am particularly drawn to your nighttime images, where lights and figures emerge from a lush darkness. You write about night blindness, that you feel “suspended, not quite yourself, not quite alone.” Beyond recreating your father’s late-night perspective, does this symbolism speak to a larger theme in your work?

RNW: Sometimes in photography, one’s limitations can be a kind of freedom. To navigate my night blindness, I steered clear of the busier state roads, to avoid the headlights of oncoming pickups or semitrucks, whose bright lights can be so disorienting to me. Instead, I traveled the dimly lit back roads, which were easier on my eyes. For miles, often the dark countryside would only be illuminated by my car’s headlights or a farmhouse’s incandescent porch light or a barn’s mercury vapor light — and on clear nights, the stars and moon.

In the book, the night is less a backdrop than a kind of presence. Driving in the dead of night, I could imagine my father driving his 1964 Chrysler 300 on these same roads concerned about a homebound patient, or his Quaker great-grandfather making house calls in his horse and buggy just after the Civil War. Driving in the dark, I often felt closer to my father and to our Quaker family ghosts — who were all caretakers of the land and its people. For doesn’t “care” mean “close attention”?

Perhaps it’s when we no longer can discern the details, that we truly begin to see the night.

Elizabeth Bailey is a Los Angeles based artist who uses photography to create emotionally charged imagery that explores the concepts of self, identity, memory, alienation, and longing.

Her work has been exhibited in venues including Light Box Gallery in Portland, OR; Photo Place Gallery in Middlebury, Vermont; and The Southwest Museum in Los Angeles, CA. Her photographs have been published in SHOTS Magazine, Stubborn Magazine, and Light Leaked.

Born and raised in small-town Minnesota, Elizabeth moved to Los Angeles at 18 to attend Occidental College. After receiving a BA in Philosophy, she worked a series of horrible office jobs while taking night classes in photography and graphic design, quickly becoming serious about both. Elizabeth currently works as a graphic designer and fine art photographer. IG: @elizabeth_bailey01

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

Olga Fried: Intangible EncountersFebruary 18th, 2026

-

Juliette Ludeker: Somewhere You Can Never GoFebruary 16th, 2026

-

Review Santa Fe: Elizabeth Z. Pineda: Sin Nombre en Esta Tierra SagradaFebruary 6th, 2026

-

Review Santa Fe: Carolyn Monastra: Divergence of BirdsFebruary 2nd, 2026