Photographers on Photographers: Kendall Pestana in Conversation with Philip J. Calabria

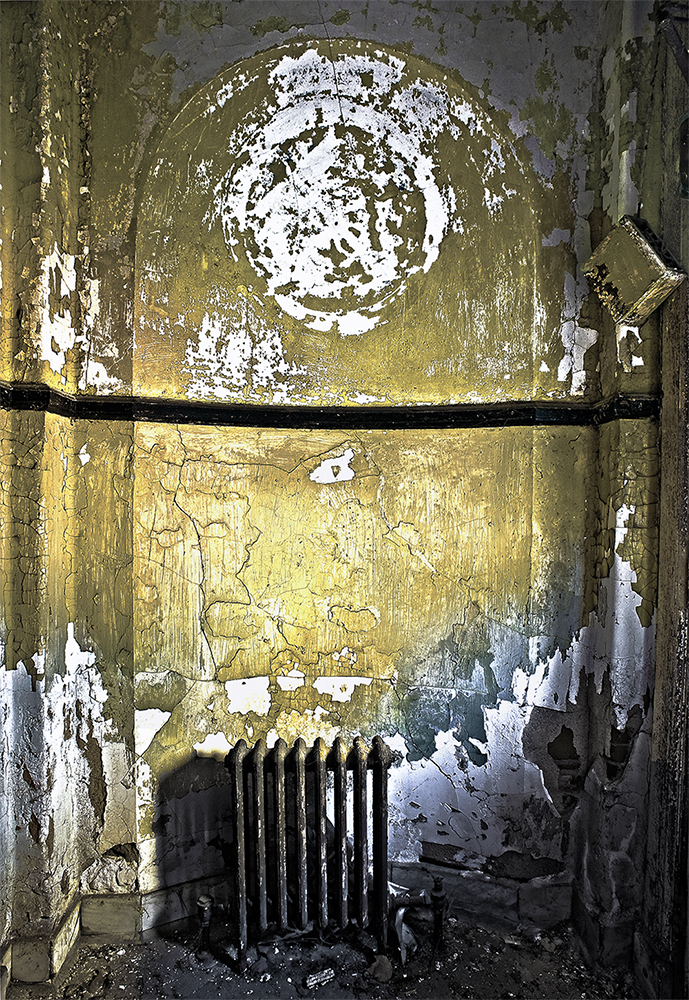

Ever since I was young and in the midst of discovering photography for the first time, I remember being equally inspired and intimidated by the stunning artistic achievements of elder family members that came before me. My great uncle, Philip J. Calabria, is one such figure. Though I can’t recall ever meeting him in person until much later, I grew up hearing my mother and grandfather talk about what an incredible photographer he is and that I should become familiar with his work. It wasn’t until 2016, however, that I finally got the chance. I was 18 and it was the summer before I left home to go to art school. Philip happened to have a solo show of “The Stilled Passage” on view at The Brattleboro Museum of Art, and I jumped at the chance to finally see it in person. From the moment I walked in, I was totally floored by his work. The quality of light was so ethereal, and each color and texture was rendered beautifully. More than that, though, the images had a haunting quality that stuck with me indefinitely. While my own images are quite different thematically, Philip’s work on The Stilled Passage was incredibly influential to me in terms of lighting, mood, and color. It’s for these reasons that I selected Philip to interview, and I’m very grateful that Lenscratch gave us this opportunity to connect.

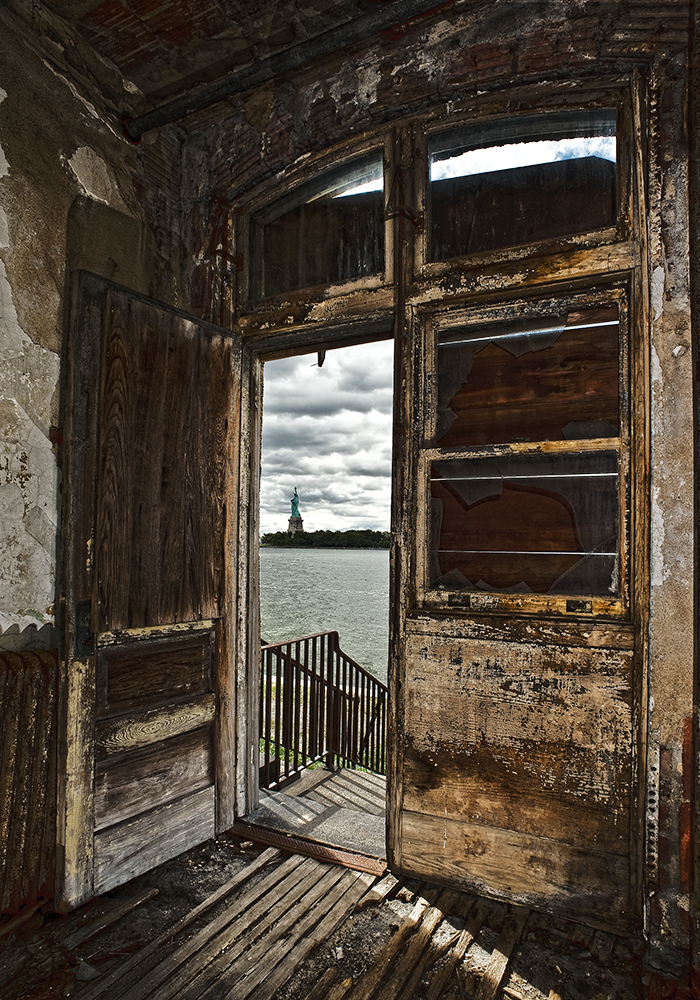

Philip J. Calabria (b. 1948) is a Massachusetts-based artist and educator known for his painterly, ethereal approach to the genres of studio and field photography. In his career spanning over four decades, Calabria’s work has been featured and collected by numerous institutions including The Archives of American Art – Smithsonian Institution, The Howard University Gallery of Art, The Museum of Fine Arts Santa Fe, and The Ellis Island Museum of Immigration. He is also the recipient of numerous grants and fellowships including the Charles E. Culpeper Foundation Grant, the Vermont Studio Center Fellowship, and the University of St Andrews Teacher Fellowship.

Kendall Pestana: How did you come to photography?

Philip J. Calabria: After graduating college with a B.A. in literature, I started writing a novel. However, the work was best in its descriptive sections. So, I turned instead to teaching myself the rudimentary skills of black and white photography.

KP: How do you measure success in your career?

PC: Having remained true to my aesthetic for 40+ years, whether in the film based or digital realm. Photography is simply another means to answer questions, and as long as that happens, I continue with it.

KP: How did you get your first “break”?

PC: Going to the University of New Mexico in the 1970s where one was constantly surrounded by well respected photographic artists and teachers. Along with this, the continual influx of their friends, colleagues, collectors & the such from the art world. The graduate classes were small and populated by talented and driven students from all mediums who spent much time in their studios.

KP: Who are some of your influences?

PC: Visual artists – Eugène Atget, Frederick Sommer, Walker Evans, Mark Rothko, Andrew Wyeth. Innumerable poets & other writers.

KP: Your father, my great-grandfather, came through Ellis Island as an immigrant in 1912 and ended up becoming a highly successful cinematographer in the 1950s and 60s. Do you feel like he had any influence on your aesthetic as a photographer?

PC: No.

KP: No?

PC: No, he did not. My father saw cinematography as a way of putting bread on the table. His aesthetic was primarily determined by who was sitting in a director’s chair, and that ranged from Hitchcock to Irwin Kirshner and other directors. But no, it did not. And by the time I got into photography, he was out of cinematography and retired. He obviously didn’t live long enough to see The Stilled Passage.

KP: Speaking of the Ellis Island work, I’m wondering what the significance of Ellis Island is to you?

PC: Well, that then certainly connects with my father. When I was offered the opportunity to photograph on the South End of the island, one of the first things I did after touring the South End was actually to go to the Honor Wall. I don’t know how much you know about Ellis Island, but on island number one, which is the island that has been restored and was the main island for the immigration center, one of the ways that money was raised to do the restoration in ’96 was through contributions. There were a lot of corporate contributions, but there were also a lot of individual contributions. One of the ways you could do that was by buying an engraved portion of what they call the Honor Wall. It’s a stainless steel ellipse that is on the backside of island number one, and you could pay to have the names of family and friends who had come through Ellis to be engraved on that wall. We did that for your great grandfather. So that was the significance of it.

Plus, and this doesn’t show up anywhere else, Elia Kazan, I don’t know if you recognize that name, but he was an Academy Award winning director who did A Streetcar Named Desire, Viva Zapata! and On The Waterfront. Both he and my father grew up in the same Lower East Side section of Manhattan, only a few blocks away. And although Kazan came to the United States from Greece and was five years younger than my father, they didn’t interact until later in the sixties when Elia Kazan decided to do a motion picture about his experience of coming from Greece to the United States. He directed this film called America America. You can obviously go on IMDB and see all this background, but the grand intersection here is that my father did a number of the shots in New York for that film.

KP: Wow, I didn’t know that.

PC: Yeah. So that ties into Ellis Island as well. And when my show opened the first time in Ellis in 2012, not the subsequent one in 2016, that was the hundredth anniversary of my father having gone through as an immigrant in 1912. So a lot of serendipity there in that regard.

KP: Over the span of your career, what are some lessons that you’ve learned along your artistic journey?

PC: The main lesson, the most secure and succinct lesson that I have learned is just to keep hitting the nail on the head, just keep doing it. You really have no way of knowing, at least I feel this way, you have no way of knowing where it’s going to take you, what the result is going to be, even as much as you proceed and feel it what the outcome is.

It quite literally is just getting up in the morning and going to the studio. Even if you don’t feel like it, even if you had a completely terrible klutzy kind of day the day before or even if the day itself turned out to be klutzy, just keep at it. And I think that’s the most significant lesson I’ve learned. And I’ve heard it from other artists in other mediums whether it’s photography or not. I have many friends who are writers and poets. In grad school, I hung out primarily with the painters because I felt that their approach really echoed what I was doing.

KP: That’s awesome. I really agree that consistency is important. Sometimes I find that when I take too much time off from a project, it’s so much harder to get that momentum back.

PC: Right, that brings up a good point though, Kendall. I have however, found that when I do get to that point of when I feel things are completed, I need time off. I really don’t go right in and say, “All right, what’s the next project?” I do need a little bit of detox as it were.

KP: Yeah, you’re right, there’s definitely an important balance to be found there. It actually ties into my next question: How do you maintain a creative practice today? Does it look different than when you were younger?

PC: Well, that is determined by my illness, number one. Although I am still of sound mind, I am not so much of sound body anymore, and I can’t drive. So that completely takes out of the game my being able to do field work at the present time. I have gone back to the still life aspect of my expression, but now it is absolutely all digital and it’s all using the scanner and then recreating from there. The wonderful thing about scanners is they have a depth of field, so you can do three-dimensional objects, even if you don’t have a 3D scanner. They drop off after a while, but still, I’m able to do that. I have completed two more portfolios that are exclusively done with the scanner as a camera and I also revisited a project that I had started in 2015 that revolved around visiting certain small towns along the Connecticut River. I completed two portfolios on that, as well. They were endowed projects and I don’t know that they represent my best work, but I had a grand time revisiting them and exploring what I saw then and what I saw now in the work. In fact, I think one of my best pieces that I’ve ever done came out of that series.

KP: That’s awesome. I love hearing about how your process has evolved and how you’ve adapted to the barriers with your illness. I find that very inspiring.

PC: Thank you. Yes. Otherwise, I mean, there’s only so many books I can read.

KP: The last question I have is, do you have any advice for young artists? I know we already talked a little bit about some of your lessons learned earlier.

PC: Yeah, I’m trying to remember the line from, which movie was it? I can’t remember, but essentially it goes like this, “Never give up, never give up, no matter what it is, never give up.” I mean, that’s the best advice I could give to anybody. You’re going to encounter roadblocks, you’re going to encounter dead ends, you’re going to encounter materials that don’t work. There’s going to be equipment that breaks down. Whether you’re a photographer or a painter, you’re going to end up in situations in which you’re uncomfortable. And maybe you say to yourself, “I shouldn’t go there,” but maybe you should. You know? Trust your gut. I think this medium overtalks itself unlike other mediums. For example, some other photographer might say to you, “Oh, what f-stop is that?” Or, “What format are you using?” Or, “Are you using Photoshop?” Painters never ask each other those stupid questions. And it may go back to being cast as a sort of stepchild of the arts when it came into being in the 19th and early 20th century, I don’t know, but I think there’s more talk about photography and more talk about its technique than of any other mediums that I know. Don’t overthink it.

Kendall Pestana (b. 1998) is an interdisciplinary artist and set decorator based in Acton, Massachusetts. Spanning sculpture, photography, and animation, her work is an investigation of psychological and bodily space through the lens of gendered violence, illness, and objectification. In 2020, Kendall received her BFA in Photography from Massachusetts College of Art and Design with Departmental High Honors and was named among Lenscratch’s Top 25 Emerging Artists to Watch.

Follow her on Instagram: @kendall_pestana

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

Paccarik Orue: El MuquiDecember 9th, 2025

-

Lauri Gaffin: Moving Still: A Cinematic Life Frame-by-FrameDecember 4th, 2025

-

Dani Tranchesi: Ordinary MiraclesNovember 30th, 2025

-

Art of Documentary Photography: Elliot RossOctober 30th, 2025

-

The Art of Documentary Photography: Carol GuzyOctober 29th, 2025