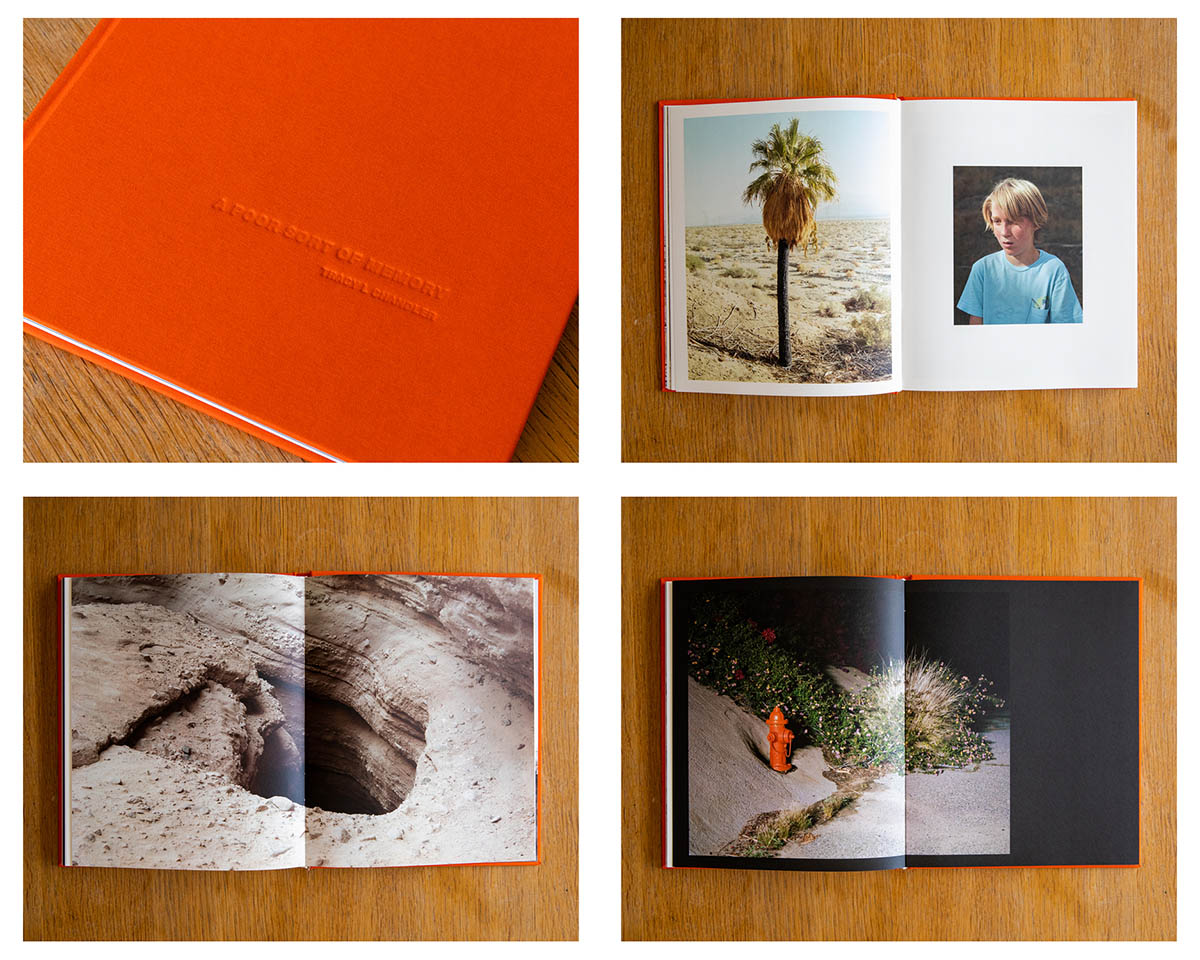

Tracy L Chandler: A Poor Sort of Memory

Chantal Anderson sat down with fellow photographer, friend, and collaborator Tracy L Chandler, to discuss Chandler’s latest work, A Poor Sort Of Memory.

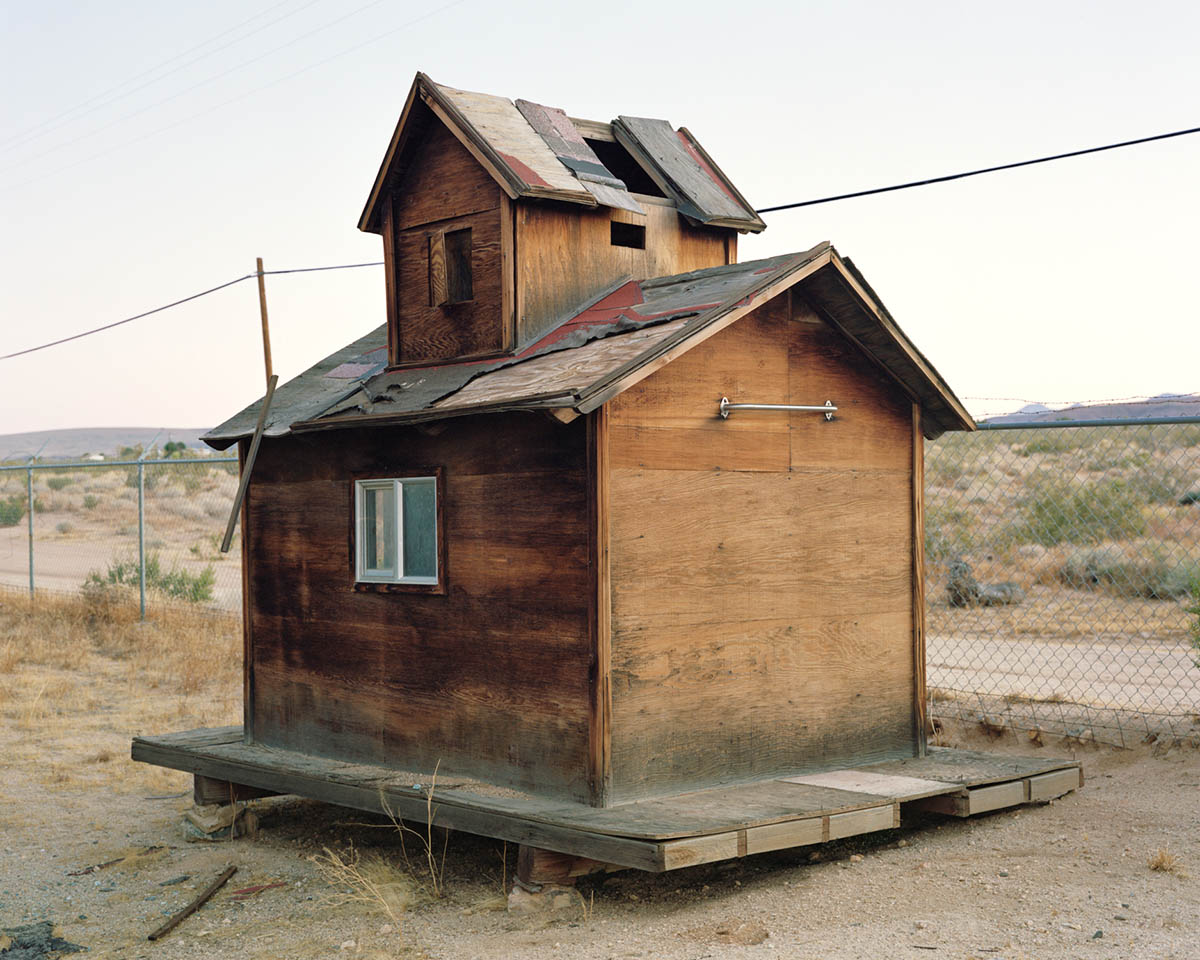

Tracy L Chandler is an American artist living in California who uses photography to explore themes of isolation, vulnerability, discovery, and coming of age. In her photography series and photobook maquette, A Poor Sort Of Memory, she mixes portraits of her son Eli, with staged constructions, landscapes, and object pointing. Working primarily alone and with a view camera, in this work Tracy retraces the course of her past as a means of coming to terms with a deeply flawed upbringing in an inhospitable land.

What follows is text transcribed from a series of conversations between friends.

Chantal: I’d love to open by asking you about your personal history with the Coachella Valley?

Tracy: Well, growing up in the desert, my experience was primarily feeling like an outsider. I was not in a city or typical suburban place like I had seen on tv. The street that I lived on dead-ended into a big open wasteland and I always felt like I was right on the edge of this vast abyss. At home there was a lot of dysfunction and I often felt unsafe or like I didn’t belong. So there was this big desert out there that was barren and dangerous but also served, for me, as an escape and private refuge. Even though I found beauty and solace in this landscape, I resented that this was my only option. I could not wait to leave.

Chantal: And you did leave– you don’t live in the desert now. So, what pulled you back?

Tracy: All things come full circle. I left the desert as soon as I could. I traveled the world and landed in NYC for over a decade before returning back to California, where I now live with my partner and son in LA. This may sound cliché, but being a parent has pushed me to reconnect with family and reconcile things with my past, all in an effort to get it right this time…be a better person and build a better future. But in building a home, I had to question how my sense of home was originally formed. For me the camera is a way to do that, a therapeutic tool for looking and reframing, and trying to pin down memory for fear of loss. The irony is that in the act of photographing, I found I was not preserving my past but contorting it, and creating something new.

Chantal: Many of your photographs from A Poor Sort of Memory document discarded objects, almost as evidence that humans were present for a time in this landscape. What do you think these objects say about where you’re from?

Tracy: As a kid I would find objects in the desert and build little collections or use them as fodder for forts and sculptures. In photographing for this project, I would use this same process of discovery and play, searching and building. Found objects are interesting to me as they are often totally out of context and can now be imbued with a projection of my own subjective meaning. I see my constructions and object portraits as metaphors. I often use simple compositions and present the item front-and-center, asking the viewer to contend with the conceptual meaning of the object itself. I have my own ideas about what they mean, but I appreciate the viewer will bring their own.

Chantal: The objects we encounter in this work, a crushed “Lost World” vhs tape, a lone mini motorbike, a glass door with no frame— seem to reveal less about geography and place, and instead inhabit a more psychological sphere.

Tracy: You are right, this is not about place. The desert is a backdrop, a container for presenting this subjective experience of coming of age. It may point to drought or emptiness, sure, but there is nothing tying this to one specific location or another. We don’t get a sense of the environment outside of this narrow view I present in the photographs. The specificity comes from the lived experience I bring from growing up here.

Chantal: In one image we see handcuffs linked between the frame of a car door and a steering wheel. In another, a sinkhole opens into an infinite abyss. There are scenes of entrapment and also moments of promising escape in A Poor Sort of Memory. I wonder if this push and pull was a discovery that you found later in the editing of the work or if this conflict was present while making the images?

Tracy: That’s a very good question. I think I found it in the editing. It wasn’t until then that I was able to see the work from enough distance to pick out the motifs on a conscious level. When photographing, I was making pictures that were connected with specific memories. I had no intentions for any one theme or another. I now realize sometimes I was subconsciously making pictures about confinement. They had a suffocating feeling for others but for me they had a familiarity that was darkly comforting. And conversely the theme of potential liberation, holes, doors, windows, all throughways to another place, a means to move beyond the discomfort of the present.

Chantal: I’d love to know more about your process of tracing your past. Do you plan out sculptures and places to visit? Or is it more of an aimless wandering or walking that brings you to your images?

Tracy: I would start out by visiting specific places that I would frequent as a kid. Maybe an old skate spot or abandoned house I’d used as a hideout. I would visit places from good memories and bad, some were sources of real pain. Sometimes there would be a picture there but oftentimes not. Maybe it wasn’t how I’d remembered or things had changed too much. So I would turn around and oftentimes there would be something behind me… a dirt road, a found object, something that would lead me to something else that resonated with the feeling state of the memory more than the original location itself. This became my process. Start with the site of a specific memory and follow the breadcrumbs from there.

Chantal: A Poor Sort of Memory features a young boy, your son Eli, as the only human we witness throughout the body of work. I’m curious how you see him in this journey, as a chaperone of sorts or more of a sun that we are orbiting around?

Tracy: Oh wow. It’s a little of both. Looking at these pictures, it is now clear to me I was trying to stop time and its degradation of memory. I set out to use Eli as an avatar of myself and to tell an old story. But now I see that I was also trying to preserve him through photography, to literally freeze time, and keep him from growing up and away from me. I was also trying to preserve myself through an effort to pin down these old memories. To stop all things from fading away. But if that was my intention, even subconsciously, I failed. Like a slippery fish, the more I tried to hold on tight the more they would get away from me. Through the making of this work, I had to really let go of my intentions, conscious and otherwise. Eli is his own person. He was not a mannequin to do my bidding. He was an adolescent with plenty of opinions. A reluctant participant. I had to give him some control, contend with him as his own being, and see him as he is. Taking Eli out of his day-to-day and placing him in the context of my hometown brought forth a totally new creation. A fiction. And he became the protagonist of this new narrative.

Chantal: Eli’s the recurrent character throughout the body of work, but it doesn’t feel like it’s only about him. There are so many layers to it. I wonder if he’s supposed to feel like the owner of these objects?

Tracy: Yeah. I think he becomes another metaphor. The shoes that you can put yourself in. A window and a mirror. A portal for you to enter the work.

Chantal: Speaking of portals, throughout A Poor Sort of Memory we are taken on a journey laden with passageways, dead ends, and infinite abysses. I would love to hear more about what these transformative spaces mean for you in the work.

Tracy: The portals serve as an invitation or a promise. A promise that things can be different, for better or worse. There is the mystery of what is on the other side. It teases and threatens. I see portals everywhere, a reflection of a desperate need to escape or a perpetuation of hope amid chaos. I use them in my work as an element of transformation, especially in my book maquette edit. They provide transition from one space to the next.

Chantal: Yes, speaking of your book, the edit starts with daytime photos, goes into the night, and then back to day again. There is a circular rhythm to it. I am wondering where in the process of making the work did that idea come forward.

Tracy: Yes, the narrative is reciprocal. I am a fan of Joseph Campbell (the comparative religion scholar). When he spoke about mythology, he often emphasized the hero’s journey and the idea that “the seeker is the mystery that the seeker seeks to know.” I believe that as much as we set out on a quest for some thing out there, we always end up finding ourselves in here. Maybe the night pictures reflect the “dark night of the soul”, that opaque abyss of the subconscious that we must feel our way through to see clearly once again. In my effort to look back, I had to let it go in order to contend with my present and my future. As I said earlier, it all comes full circle.

Chantal: I’d love to end with this question: Your work deals with memory and we’ve discussed how you use photos to work through previous ideas and thoughts you held, and to transform them into new memories. Do you think forgetting and remembering are the same act?

Tracy: Yes, absolutely. Memory is an unreliable narrator. Photography is not the whole truth either. It records only a fraction of a scene, at a fraction of a second. It’s all half-truths. It’s all fiction. In the act of remembering you are creating a new layer on top of the old one and the old one is now fading away. You are a different person now than you were when you originally had that experience and whatever baggage you’re carrying with you in the present is now baked into the remembering of that old self. Maybe there are some tendrils related to that past but really, it’s long gone. The only thing left is right here and right now. It’s like the white queen said to Alice, “It’s a poor sort of memory that only works backward”.

Chantal Anderson is an American photographer and filmmaker making work in Los Angeles, California. She’s interested in the cyclical relationship between humans and the landscapes they inhabit.

Follow Chantal on Instagram.

Tracy L Chandler is a photographic artist based in Los Angeles, California. Her work explores peripheral communities and her own personal story reflected through portraiture and narrative. Her photographs address themes of memory, belonging, seeing, and being seen. Tracy earned her MFA in Photography at the Hartford Art School in 2021 where she was awarded the Mary Frey Book Grant. Her work has been exhibited in galleries and institutions in the United States and abroad.

Follow Tracy on Instagram.

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

Review Santa Fe: Ilana Grollman: Just Know That I Love YouFebruary 10th, 2026

-

Review Santa Fe: jessamyn lovell: How To Become InvisibleFebruary 9th, 2026

-

Review Santa Fe: Julia Cluett: Dead ReckoningFebruary 8th, 2026

-

Review Santa Fe: Elizabeth Z. Pineda: Sin Nombre en Esta Tierra SagradaFebruary 6th, 2026