PROOF: Sheri Lynn Behr: And You Were There, Too

This week we are considering projects that all provide a form of proof. Each artist considers the idea from a different perspective.

My initial view of Sheri Lynn Behr’s recent project, “And You Were There, Too”, provoked considerable irony as I was keenly aware of Behr’s previous projects on the contemporary threats to privacy and the ubiquitous presence of surveillance tools and techniques in modern life. Her project surprised me for turning those tools on their head (literally and figuratively) in photographing friends, colleagues, and participants in photo events that she attended without their knowing they were being photographed. In essence she was utilizing a technique that she has warned about in the past to prove a point about the threats and fallacies of facial recognition software.

I approached my interview with her with a healthy dose of skepticism in focusing on the theme of “proof” regarding the photographic images that she created for this project. Hence, I was utterly relieved to hear Ms. Behr chuckle when I raised the issue with her as our interview began. She then stated that the question of proof in photography would better be stated as a question rather than an answer since the potential for digital manipulation of an image is rampant with the tools available in even the most basic image software. She cited a recent ACLU report that revealed that Amazon, working with the US government, conducted a test of its “Rekognition” facial recognition software that falsely matched 28 members of Congress with mugshots of criminals. Furthermore, what often is attributed as proof in facial recognition software is marred by image distortion, incorrect data matching, and mismatches or bias due to a person’s race and sex.

Behr elaborates on this theme is her artist statement for “And You Were There, Too”:

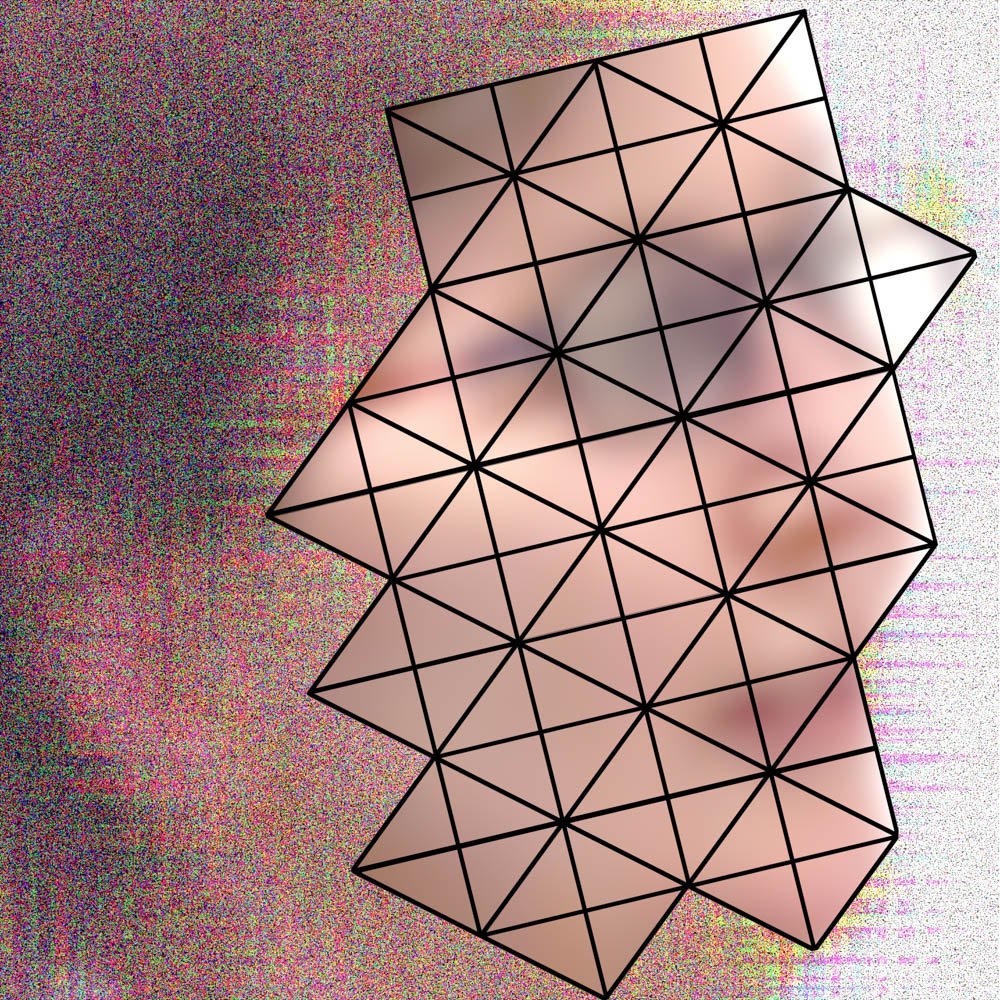

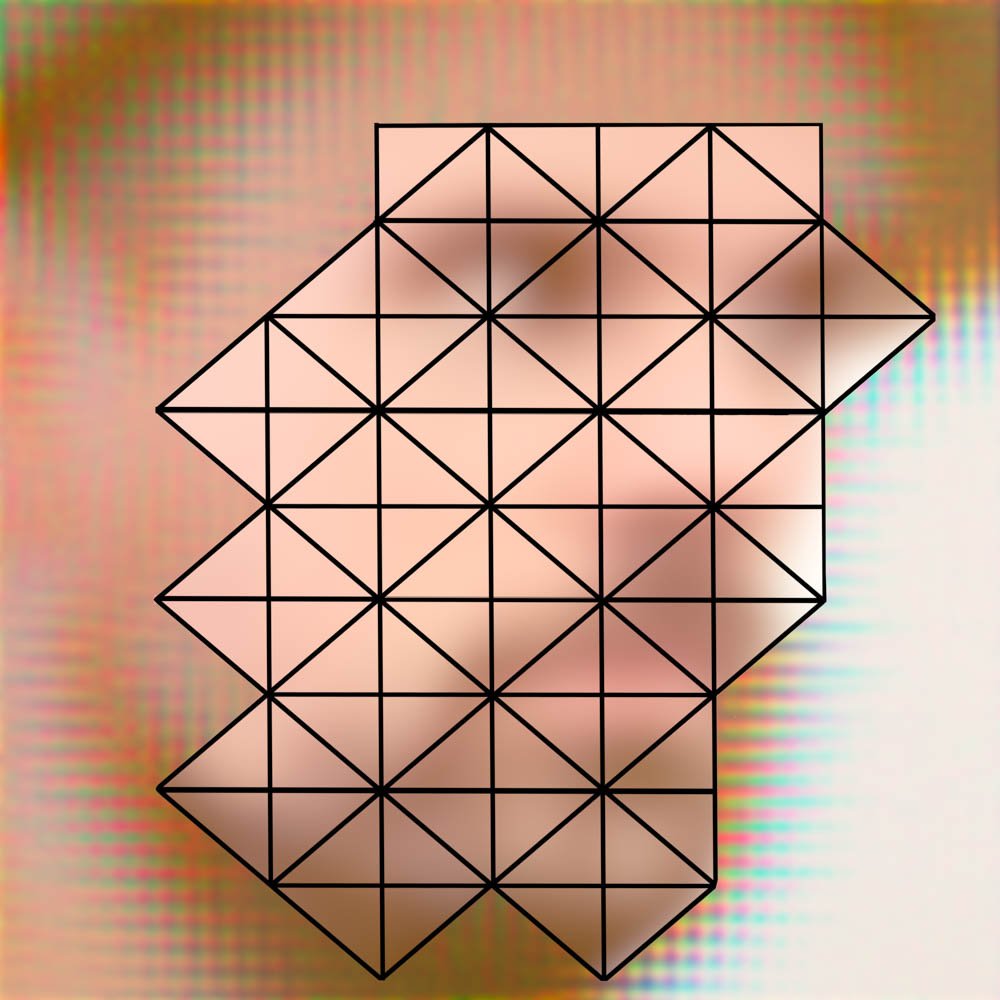

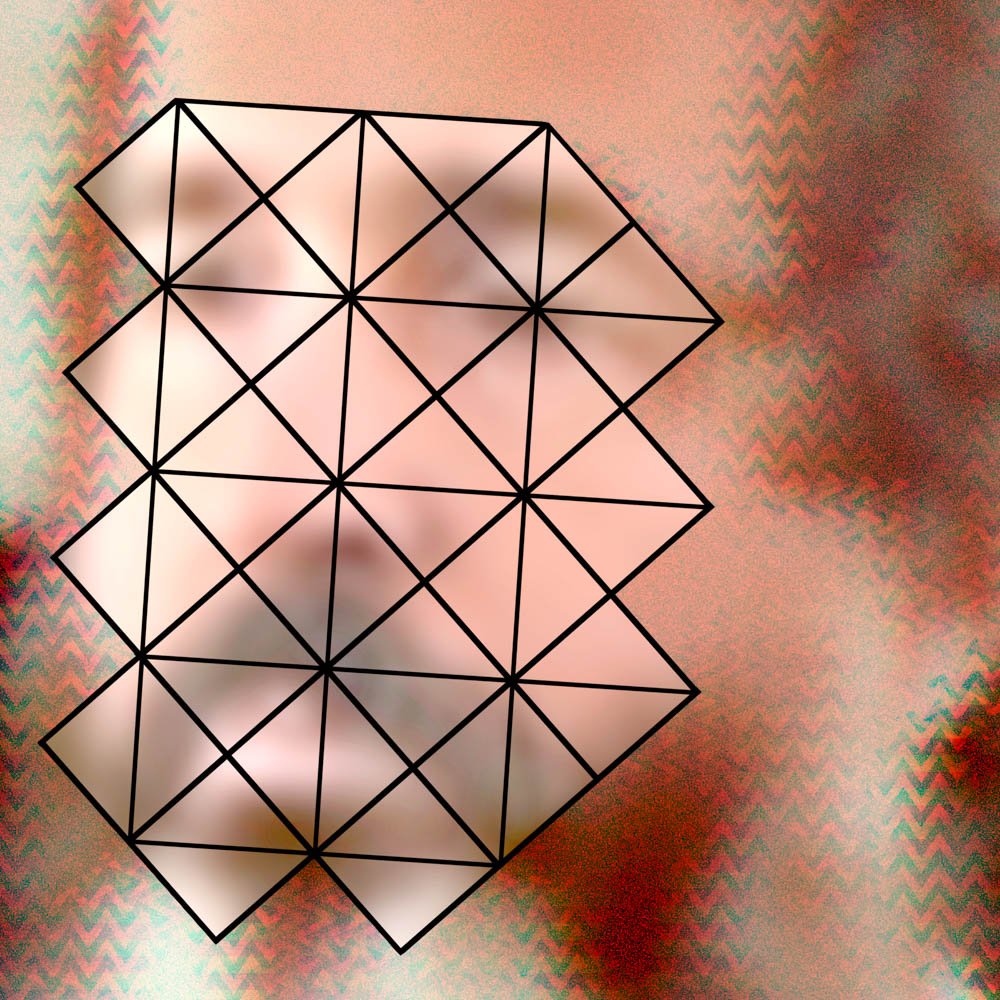

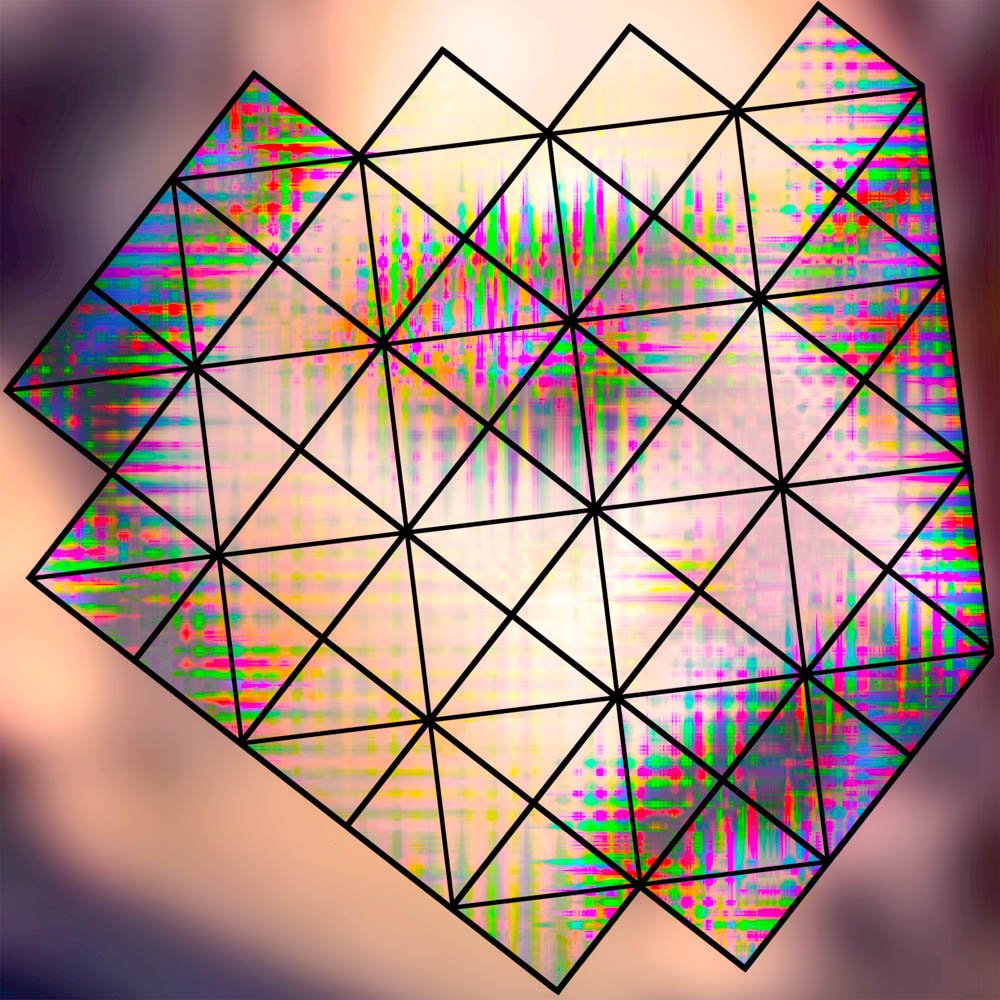

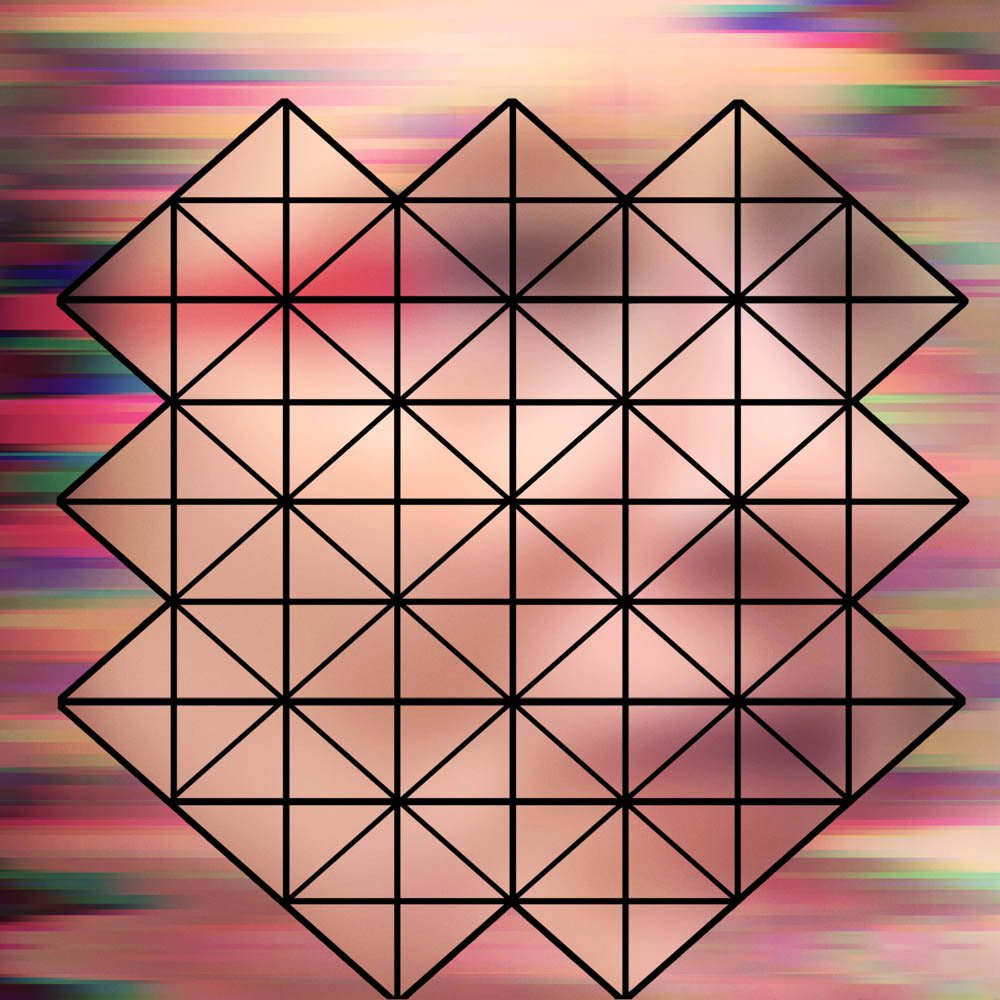

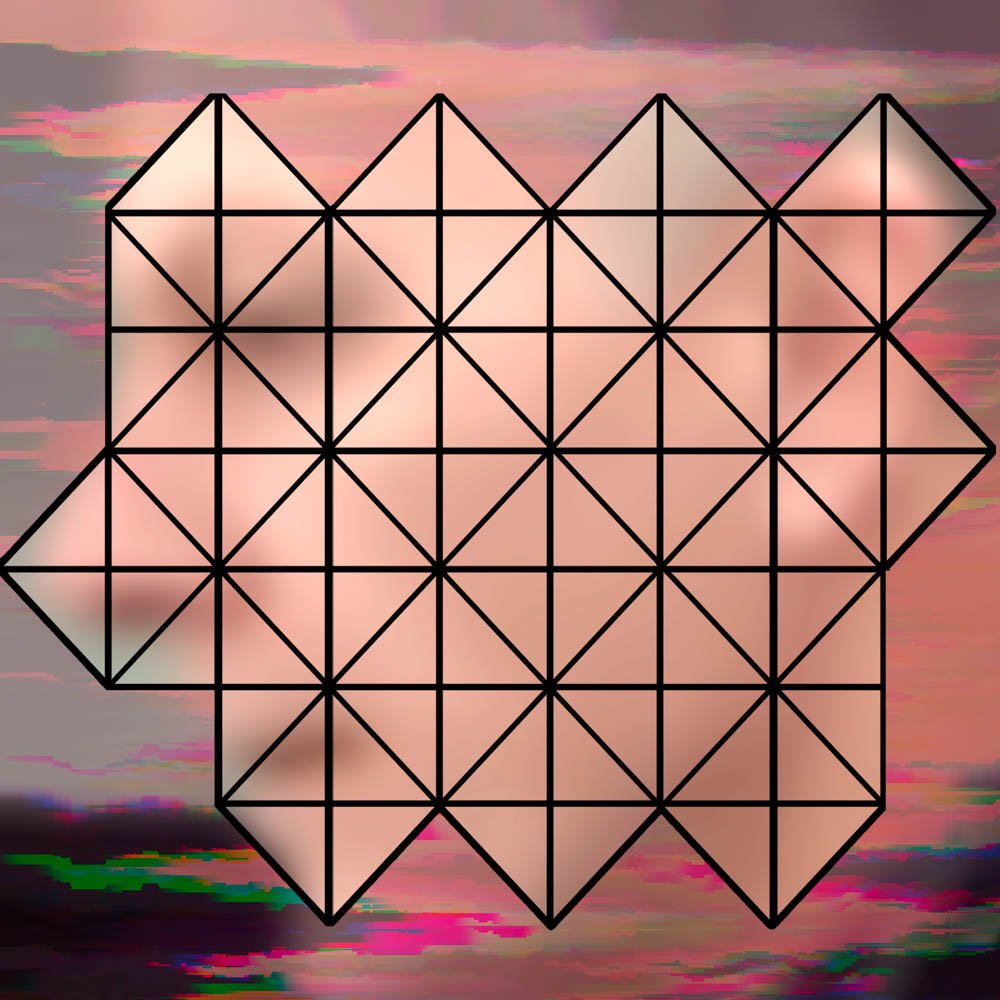

Using a camera or my smartphone to record the events I attend, I capture images of the people around me. Photography these days is so ubiquitous, who even notices? Software then extracts the faces for me, and connects them to a location, date and time, which is used as a title.

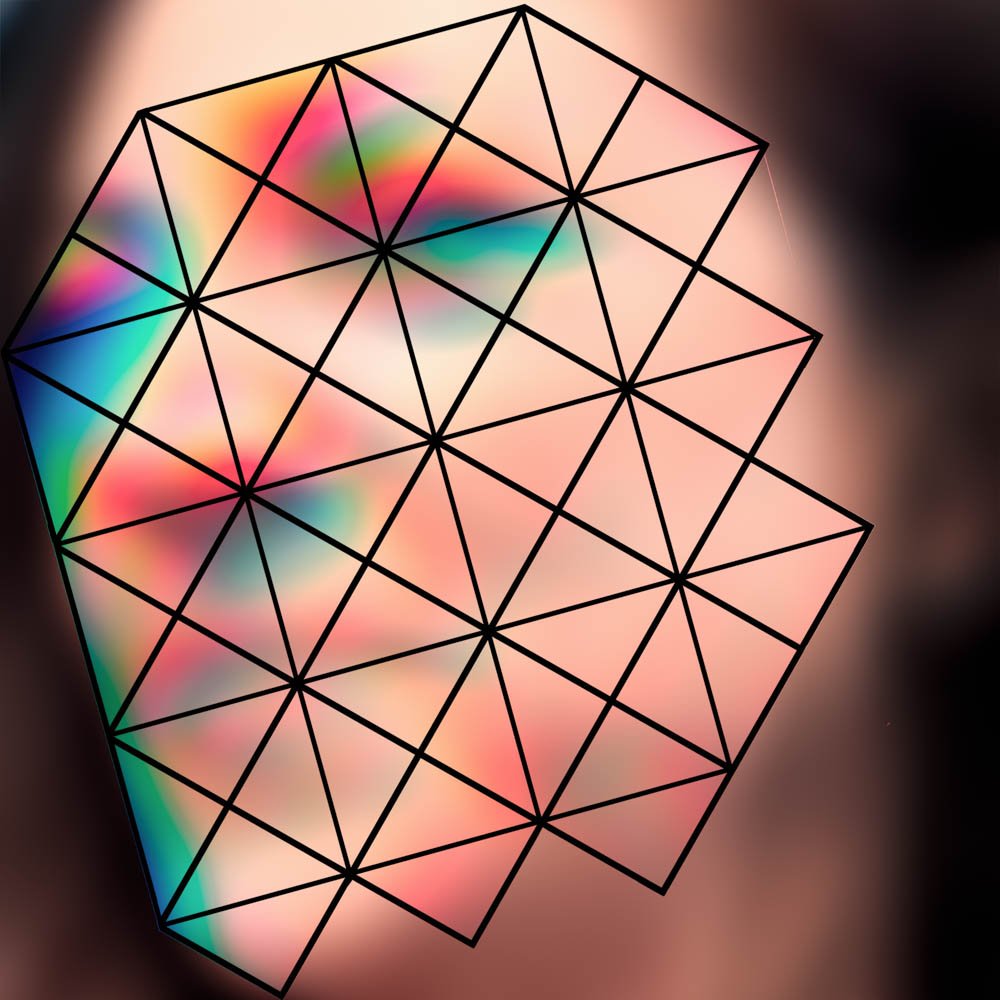

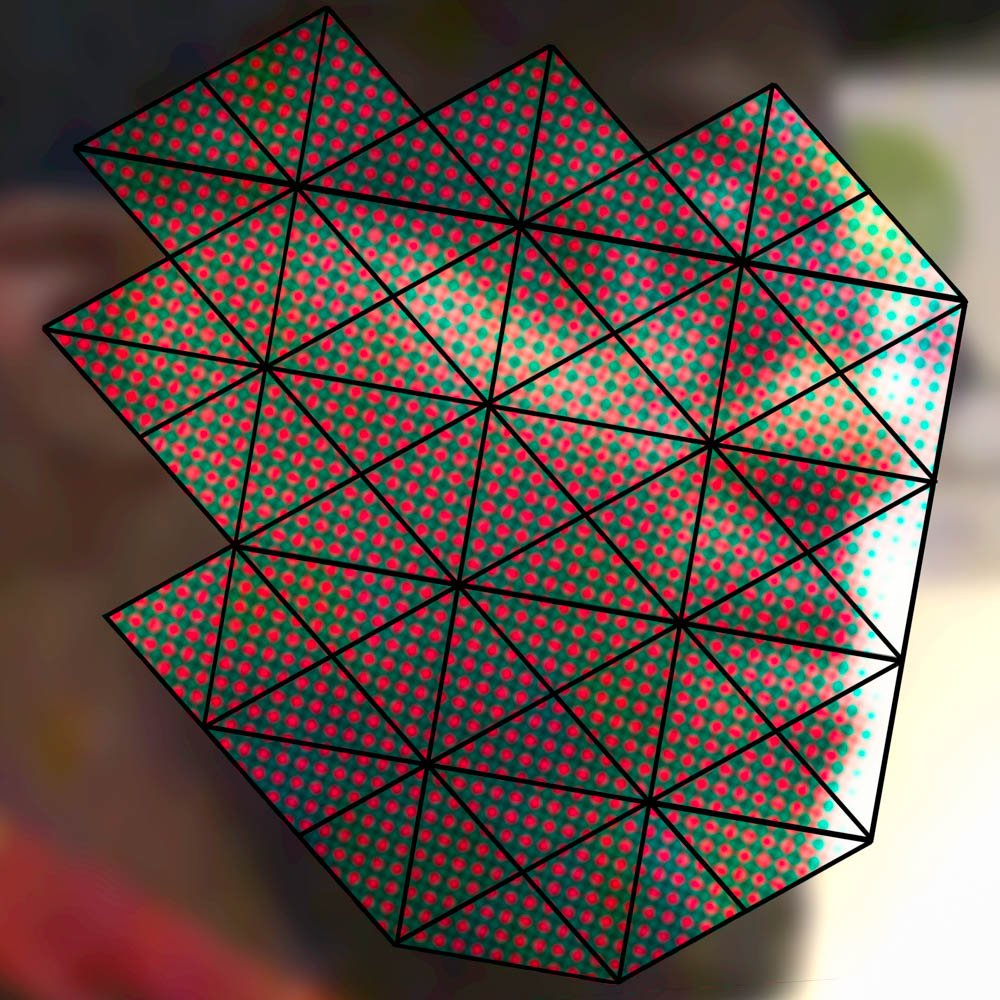

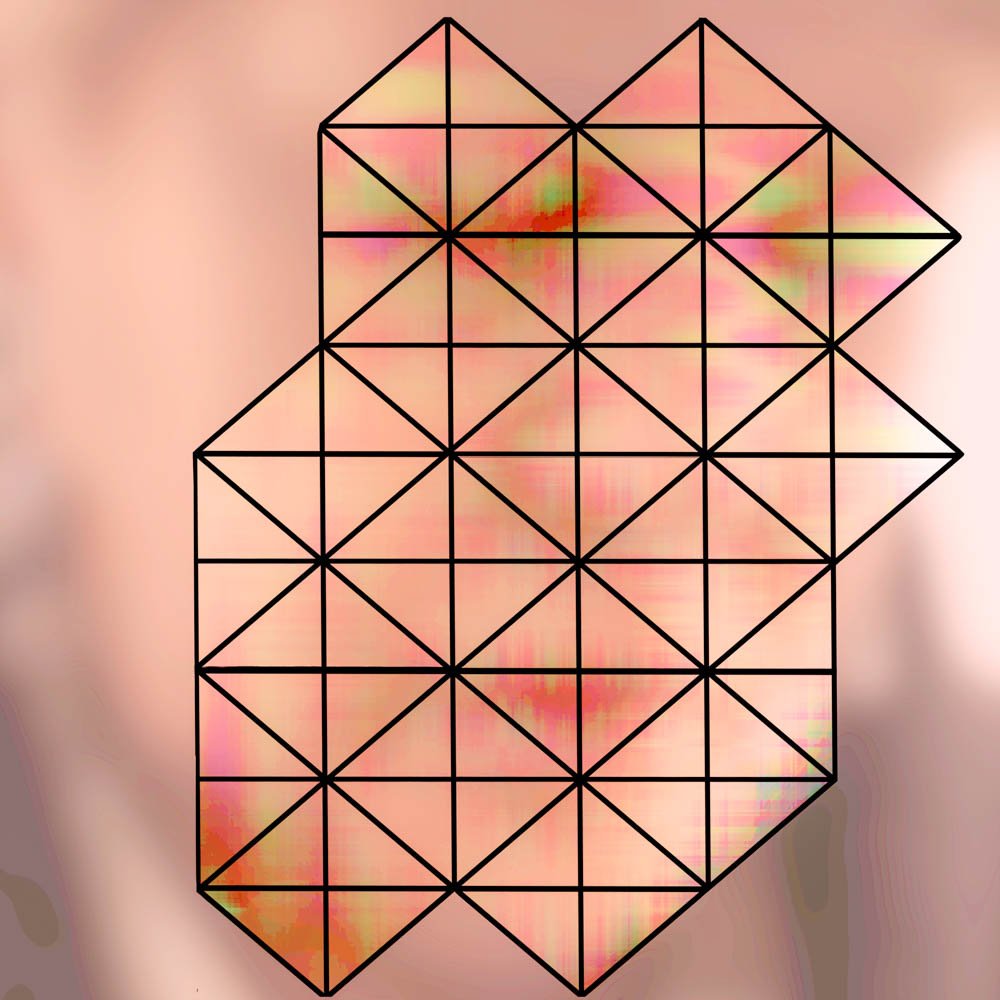

I manipulate the images, crop and enlarge the faces, and create a layer of digital glitches and errors to exaggerate the degradation of image I often see in surveillance photos on the news. I also add a custom facial recognition grid. All of this plays with perception and identification. Under the digital noise there is still a person, but reality has been altered on a screen. Size also matters, and these faces are more recognizable when small, so I enlarge the final images for print. (If you can’t see the face in the photograph, try looking at it on your cellphone) Sometimes my subjects don’t even recognize themselves.

My work shifts back and forth between highly manipulated, computer-enhanced imagery and recognizable documentary-style photographs. I know how easily technology can be used to transcend truth, distort reality and produce unintended consequences. Facial recognition seems inescapable, but it is not always accurate, especially with women and people of color. The misuse of these tools is all too possible.

Your various bodies of work including “And You Were There, Too” consistently and forcefully address the issue of technological intrusion and surveillance. To what extent do you see the irony of your own potentially intrusive pursuits in a project where you are capturing faces of friends and strangers without their knowing you are doing so?

Part of the reason I make this work, is to raise awareness of this very gray area. I still find people are unaware of the true scope of surveillance, and what’s being done with facial recognition. And when you see a picture of yourself like this when you are not expecting it, the idea becomes more real.

People have come back to me after seeing my earlier work and said that they now see the cameras really are everywhere, and they find it disturbing. Other people tell me “I don’t care, I’m not doing anything wrong.” But who decides what’s “wrong?”

Recently, the governor of Florida signed an “anti-rioting law” -an attack on right to protest- that would allow peaceful protesters to be charged with a felony if other people at a protest they attended committed an act of violence. How do you think they are going to find the protesters?

As Edward Snowden said in a tweet: “People who say ‘I have nothing to hide’ misunderstand the purpose of surveillance. It was never about privacy – it’s about power.”

Why did you opt for a customized facial recognition grid to aid in the deciphering of the individual depicted? Would it have been more of a challenge for a viewer to puzzle it out instead? Do you feel that the grid enhances or detracts from the puzzle?

It’s easier to see a face without the grid. I’ve found a lot of people don’t know what a facial recognition grid is, so that becomes part of the conversation. I was a very early adopter of digital technology, and I know how easy it is to mess with truth. Or Proof?

In a way, the viewer becomes a participant in your surveillance strategy by attempting to figure out who you photographed. In so doing, your artistic intent becomes more interactive than a traditional photo might provoke. What do you want the viewer to take from that interaction?

When the work is seen by the public, as it was at a recent exhibition at SRO Gallery at Texas Tech, or even at the pop-up show I had at my studio, most viewers won’t know the person in the photograph. They do still try to see the face in the abstraction.

Your artist statement mentions that size does matter in viewing these images and that you have opted to print them large to make their interpretation more complex. Is this necessary to convey your message?

It’s about perception, and what makes it possible to “read” an image. When I showed the work at a portfolio review, I had to get up from the table and walk backwards until the reviewer was able to see a face.

How do we interpret the images we see in surveillance photos on the news when they can be blurred or glitched by technology? It’s not surprising that some people can be misidentified.

Given that the theme of “proof” is the focus of Lenscratch posts this week, what is the inherent proof that can be found in “And You Were There, Too”? How does a digital record that might be manipulated convey “proof”?

Exactly. Can I add a question mark to the word Proof? These days, with deep fakes and other forms of digital manipulation of images, is there really photographic proof? Was there ever?

What is next on the horizon for your creative endeavors?

After we all got locked down by Covid, I started a project about Zoom. It was partly about our feelings of living virtually, and partly about privacy. I had attended a Zoom where we were told it was being recorded but the video would not be posted to protect the privacy of the attendees. So of course, I immediately thought that there is no privacy, and started making the work.

Sheri Lynn Behr is a photographer and visual artist currently based in New York City, with an interest in perception, photography without permission, and the ever-present electronic screens through which we view the world. Her project on surveillance and privacy, BeSeeingYou, was exhibited at the Griffin Museum of Photography and released as a self-published photo book, selected by Elizabeth Avedon as one of the Best Photography Books of 2018.

Behr’s work was exhibited recently at SRO Gallery at Texas Tech, and has also been shown at the Amon Carter Museum of Art, MIT Museum, Center for Creative Photography, Musée McCord, and the Colorado Photographic Arts Center, among others. Her photographs have appeared in publications world-wide, including Harper’s Magazine, People’s Photography (China), Orta Format (Turkey), Toy Camera (Spain), and The Boston Globe. She received a Fellowship in Photography from the New Jersey State Council of the Arts, a grant from the Puffin Foundation, and, most recently, a New York City Artist Corps Grant in 2021.

Follow Sheri Lynn Behr on Instagram: @photographywithoutpermission

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

Nathan Bolton in Conversation with Douglas BreaultJanuary 3rd, 2026

-

Salua Ares: Absense as FormNovember 29th, 2025

-

Ricardo Miguel Hernández: When the memory turns to dust and Beyond PainNovember 28th, 2025

-

Pamela Landau Connolly: Columbus DriveNovember 26th, 2025