Memory is a Verb: Jacqueline Walters: Learning Mandarin and the Language of Lumens

Memory is a Verb: Exploring Time and Transience brings together twelve women photographic artists exploring the liminal space between time and transience. Represented in this body of work are the universal concepts of loss, mortality, and legacy, and the exploration of what inspires us to seek solace, and reexamine our histories; subsequently unearthing discoveries about ourselves, our relationships, and our place in the universe.

This week and next we are sharing projects from the exhibition, Memory is a Verb: Exploring Time and Transience, with interviews by the artists. Today we feature the work of Jacqueline Walters who was interviewed by Dena Elizabeth Eber. Walters’s artist talk on this project can be found on the Los Angeles Center of Photography’s YouTube Channel. Her project, Learning Mandarin and the Language of Lumens, explores mark making, through the language of historical processes and Mandarin Chinese script.

Memory, often regarded as fixed or reflective of reality, in this project actively functions as a transformative shape-shifter. The ongoing tension between two seeming opposites – objective fact and subjective perception – together shape a cohesive whole, creating something larger and more nuanced than just the sum of its parts. As new insight illuminates the past, this influences our experience of the present moment; which is itself slipping into the past at the instant we seek to define or quantify it. In this manner, time is elusive, elastic, bending back and over itself; perception comes full circle.

The project Memory is a Verb: Exploring Time and Transience began as the world was besieged with fear and anxiety during a pandemic, longing for a return to normalcy. Feeling a sense of loss, we craved connection to our past and to each other. The pandemic also offered a unique moment in which to interpret things differently. Beyond nostalgia, which selectively employs memory as a self-soothing balm, our exploration reconsidered how we view the past, and what is of purpose and significance, in light of our changed circumstances.

Born in Cambridge, England, Jacqueline Walters is a fine art photographer based in San Francisco. She received a master’s degree from San Francisco State University, and a bachelor’s degree from the University of California, Berkeley. Both are in English Literature. It was through literature that she discovered photography. In her artistic practice, she explores the themes of transformation of place, layering of time and space, and memory. Since 2009 her work has been exhibited in the San Francisco Bay Area at Corden|Potts Gallery, Rayko Photo Center, Santa Clara University, and The Center for Photographic Arts; in Oregon at LightBox Photographic Gallery; in New York at the SOHO Photo Gallery; in Massachusetts at the Griffin Museum of Photography; as well as many other galleries in the United States, and internationally at the Complesso Monumentale del San Giovanni, Catanzaro, Italy, and The 11th Shanghai International Photographic Festival: Invitation Exhibition, Shanghai, China. Her work has been published in SHOTS, Black and White, and AAP Magazine. Walters’ work is part of private collections nationally and internationally. She was a 2020 Griffin Museum of Photography solo exhibition awardee.

Follow Jacqueline Walters on Instagram: @jacquelinewaltersphotography

Follow Memory is a Verb on Instagram: @memory_is_a_verb

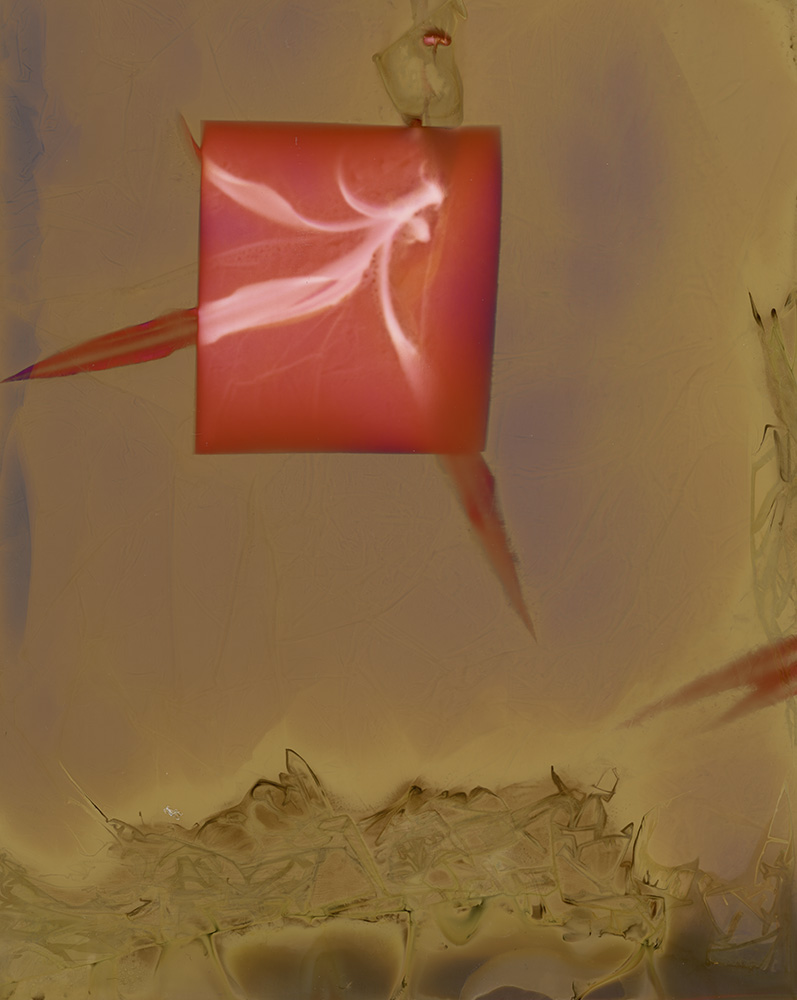

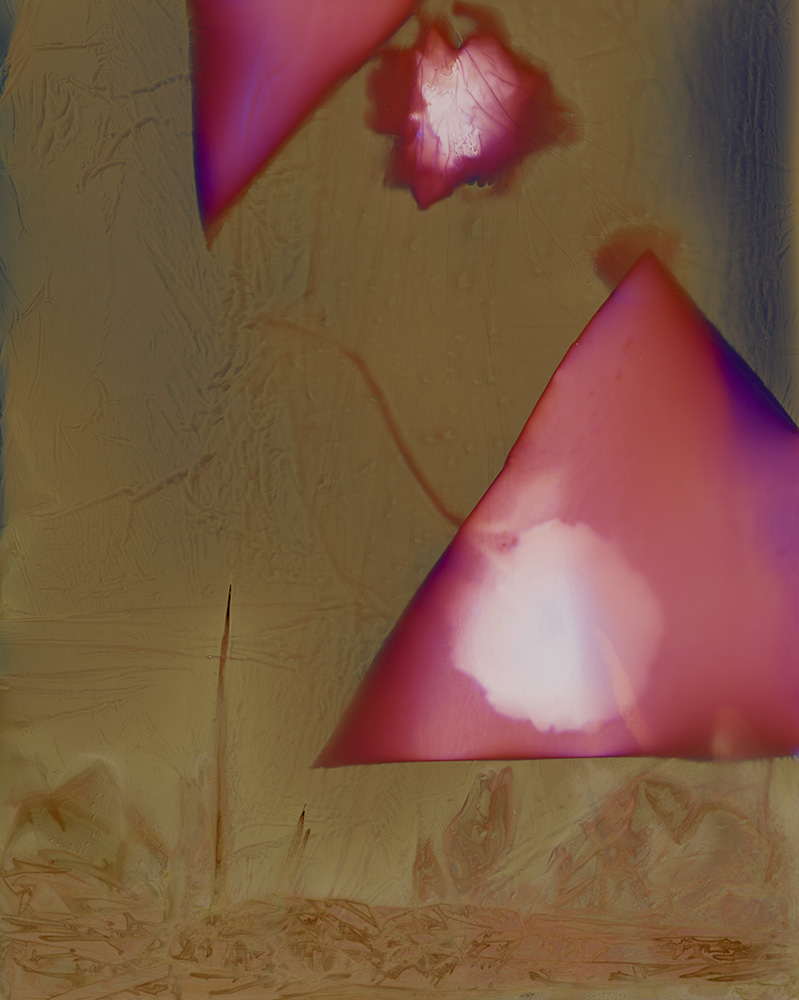

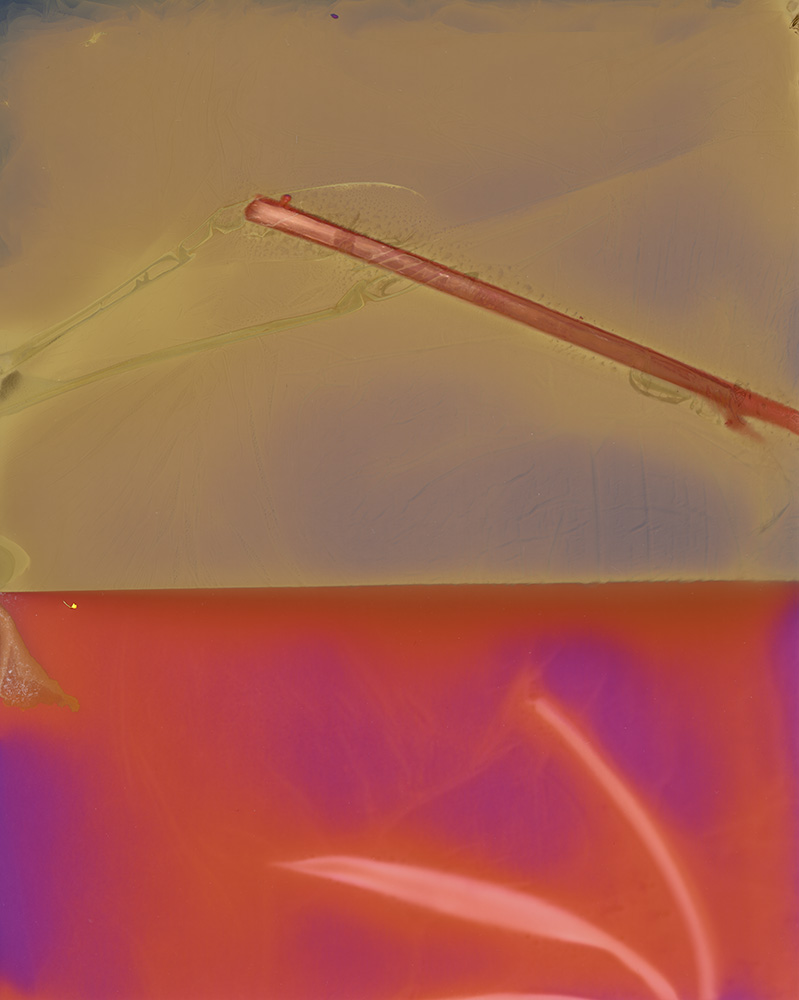

Learning Mandarin and the Language of Lumens

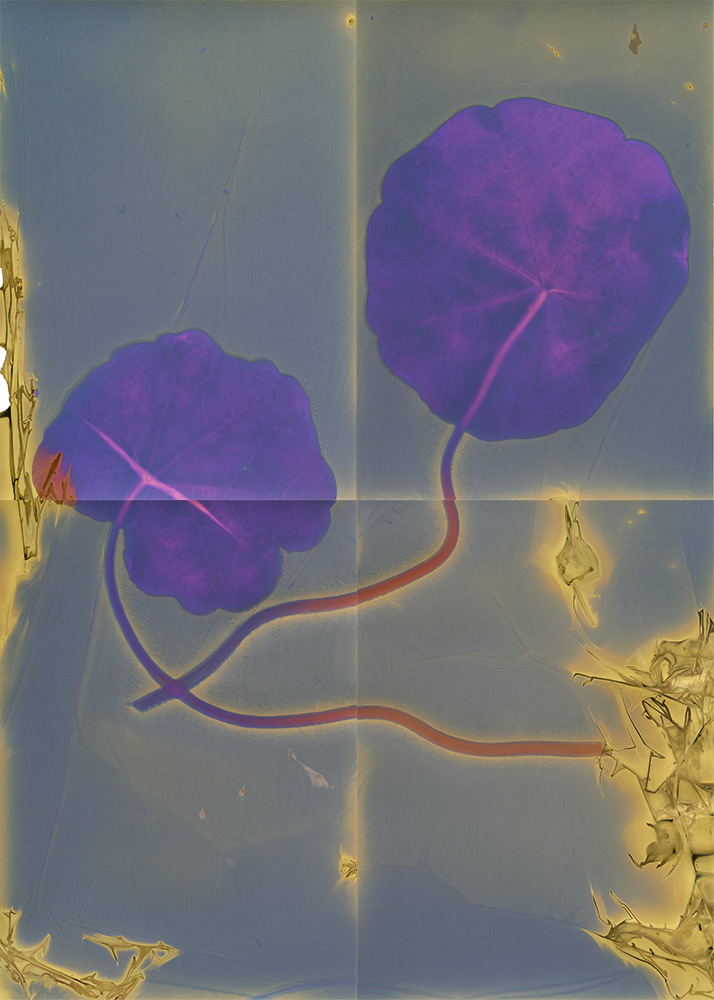

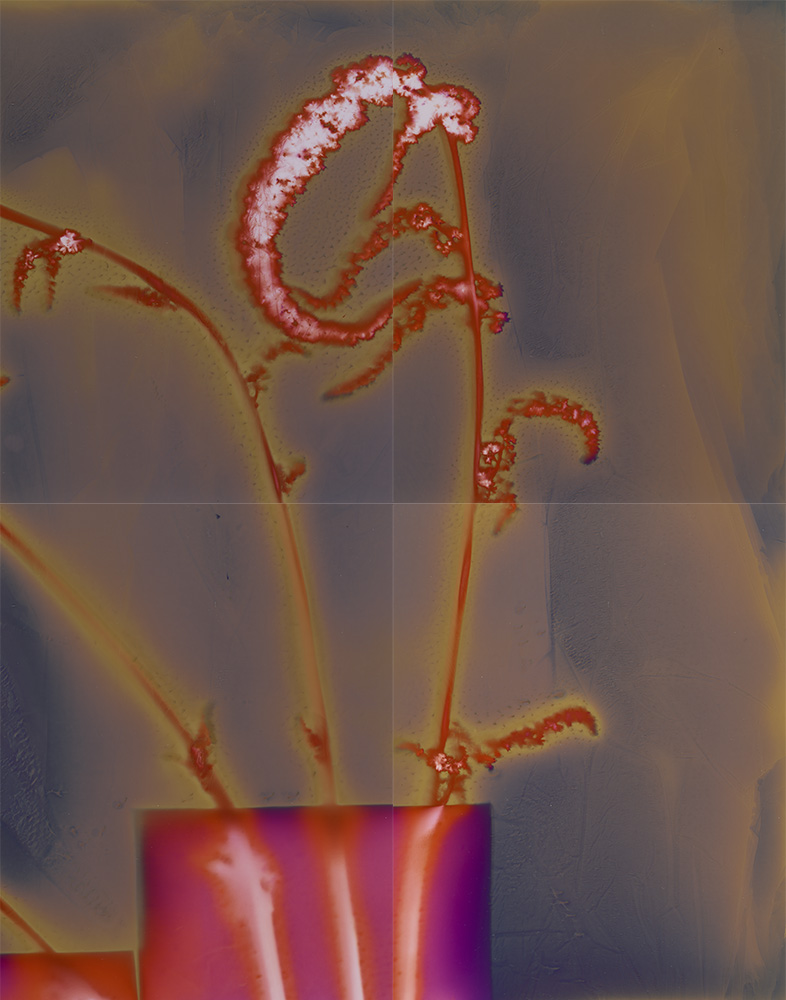

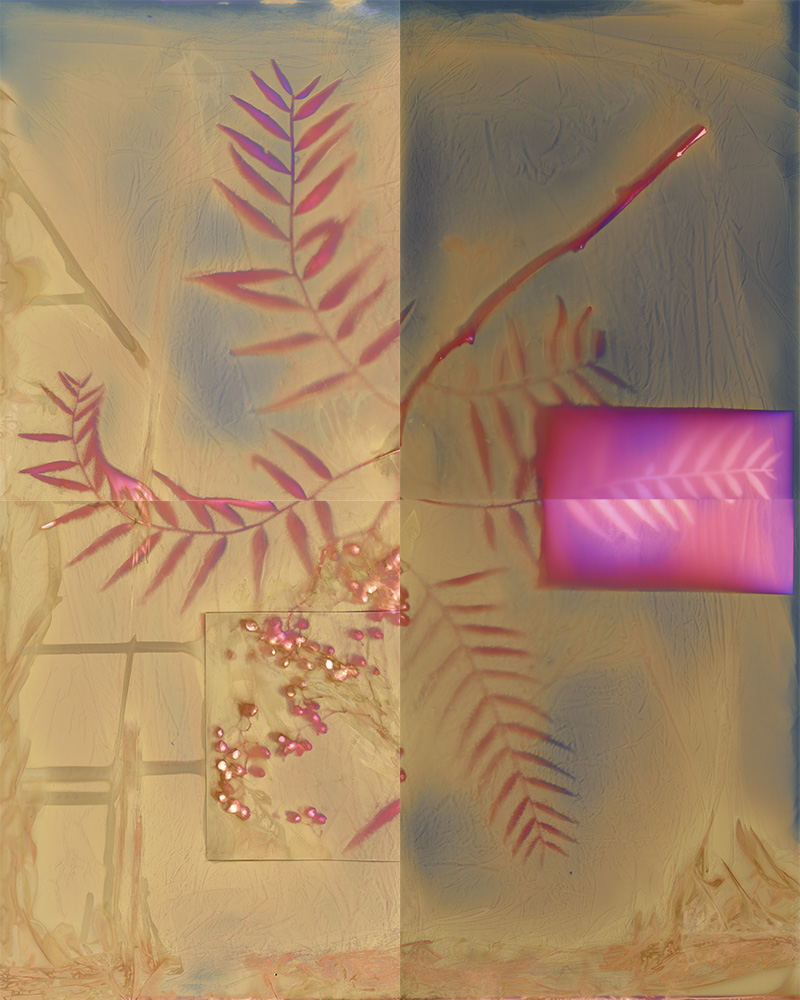

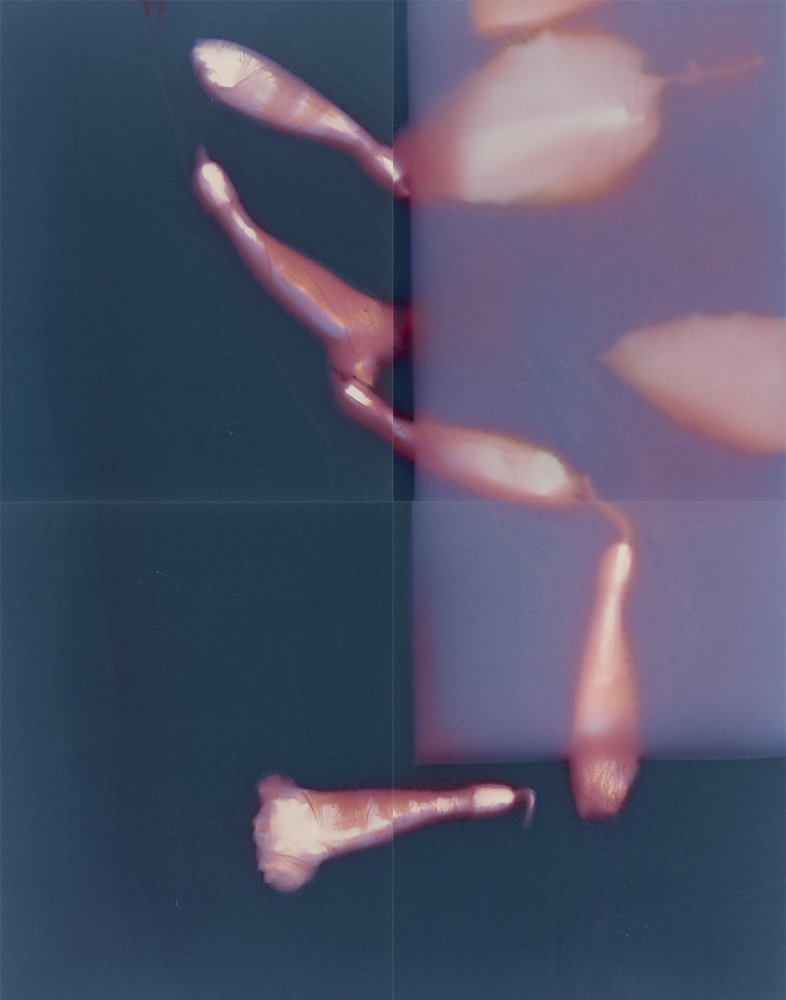

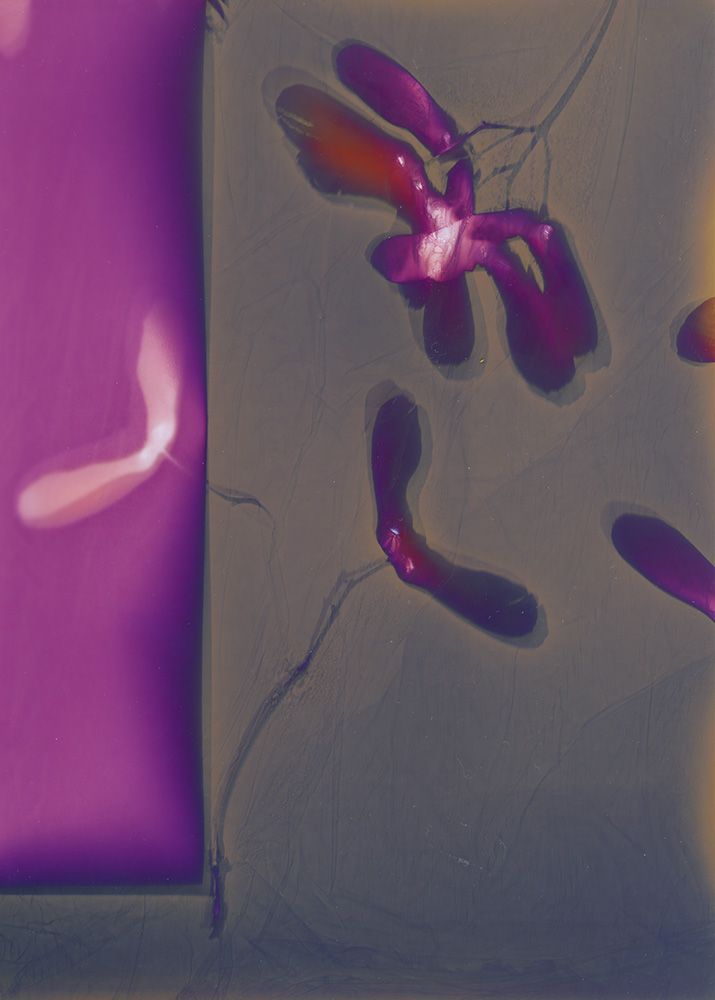

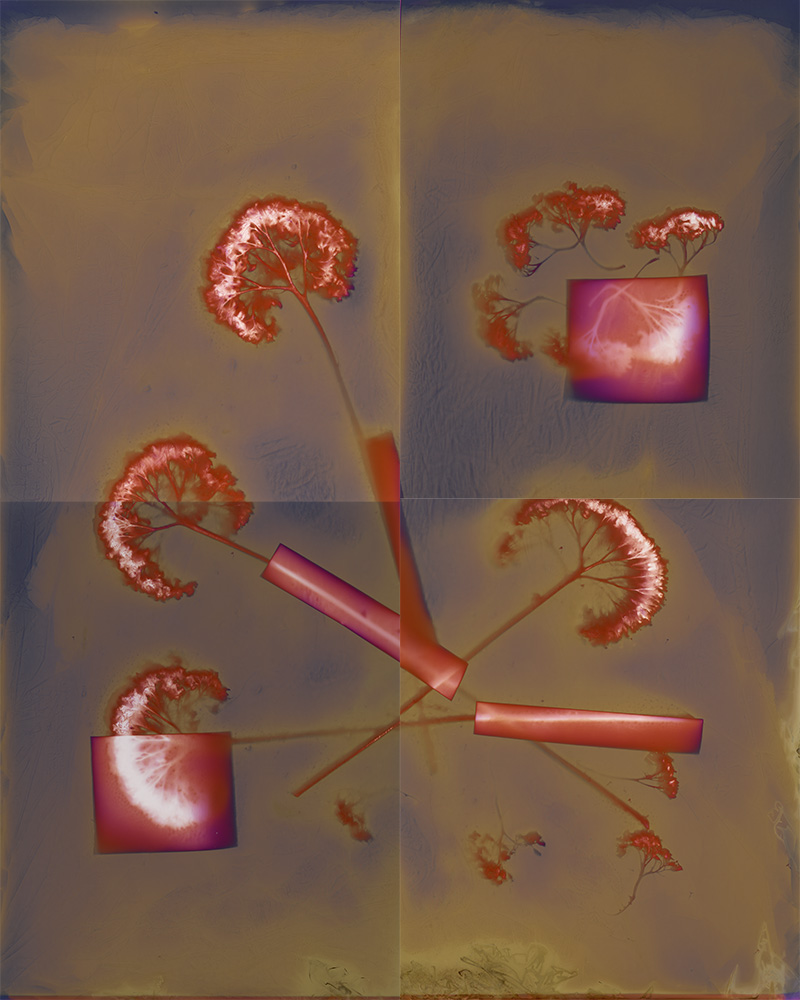

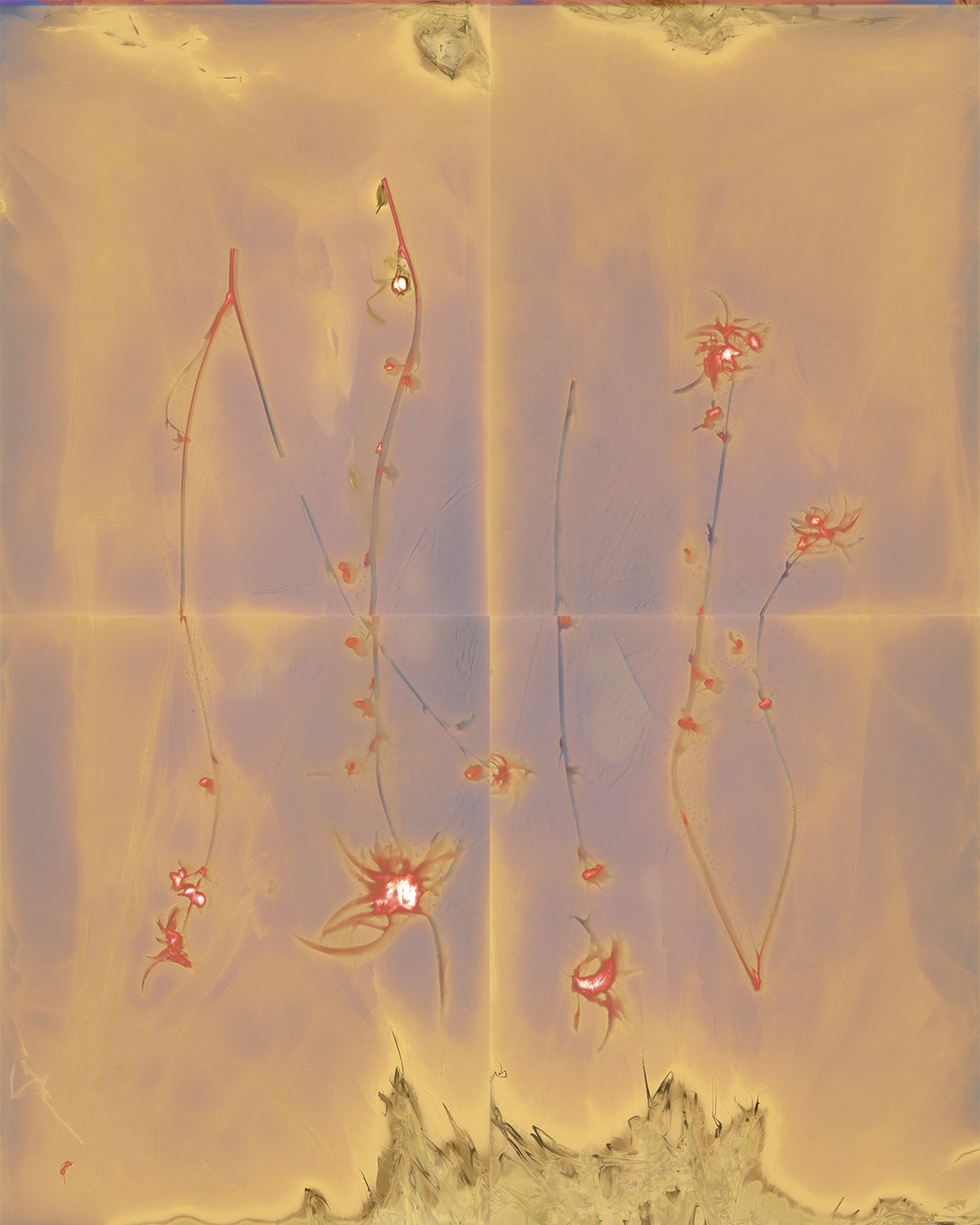

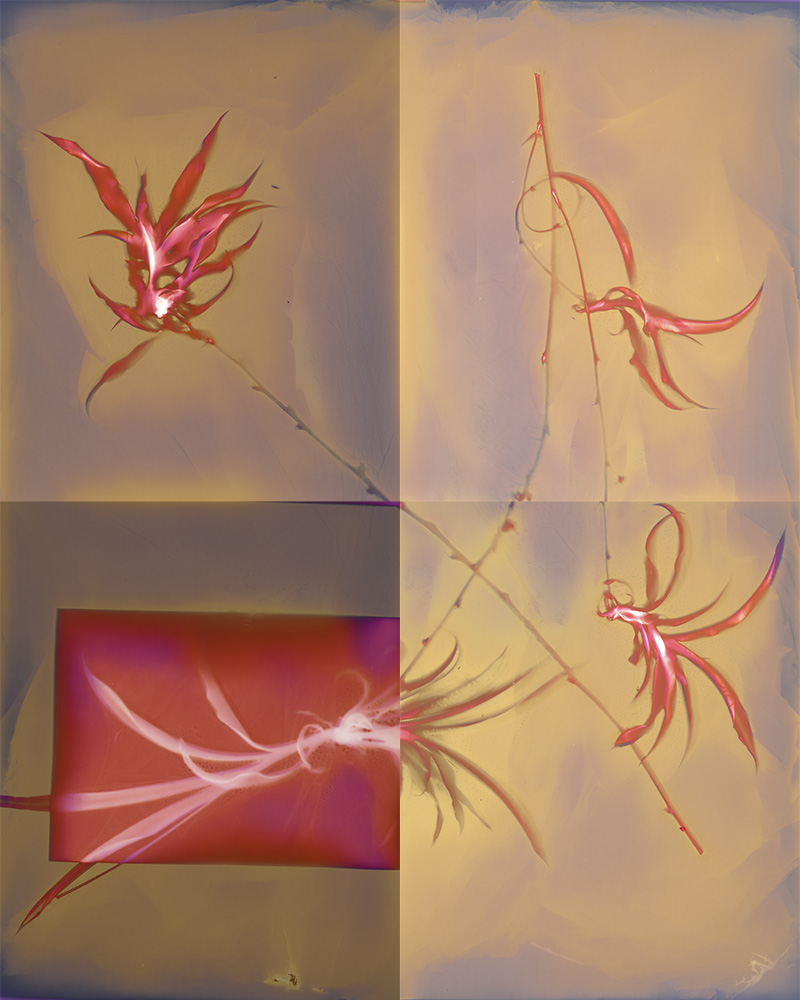

In early 2020, when I began learning Mandarin little did I realize how it would inform my artistic vision. This became evident when I began to experiment with Lumen printing. With the former, I discovered how a seemingly endless permutation of lines, dots, and dashes written within an imaginary square formed meaning through simple and complex forms. With the latter, my thoughts shifted from acquisition of craft to learning a language. In my Lumen prints, instead of ink I used various biological materials to form bold strokes and elegant lines or whispers of dots and dashes. The imaginary square was transformed into rectangles or other shapes defining the space. The written language is both a means of communication and the art form that is calligraphy. Just as the defining characteristics of the calligrapher’s hand suggests a personality, so too each paper I use reveals a different latent color as if speaking to the personality of the paper. My project, “Learning Mandarin and the Language of Lumens,” is about learning a process that harkens back to photography’s beginnings, influenced by the visual poetry and rhythmic grace of an old writing system. -Jacqueline Walters

You have a very extensive background and education (undergraduate and graduate degrees) in English Literature. Could you please expand on how this background influences your images or practice?

I came to photography through literature, and an interest in Paris of the 20s and 30s. It was a vibrant time, and photographers such as Eugene Atget, Man Ray, Berenice Abbott, Lee Miller, and Brassai were a part of those years. While working on my Master’s degree in English literature, I discovered that a well-known portrait of novelist, Djuna Barnes was made by the photographer, Berenice Abbott. The significance of Barnes for me is that her descriptions of people were so evocative they would inevitably linger in the far reaches of my mind. Through the cadence of her words, I could visualize the person both in form and personality, “…and Nora walks under fine red hair, seeking with a brogue that carries the dread of Ireland in it; Ireland as a place where poverty has become the art of scarcity. A brogue a little more defiant than Joyce’s, which is tamed by preoccupation.” Djuna Barnes Interviews: pp. 294-295.

Although at the time I did not understand its long-term significance, a thread was beginning to form between the aural and the visual, between literature and photography. In a way it could be said that I backed into photography. First, I developed an interest in the history of the subject, and then I took tentative steps in making my own work. Words gave way to images, but later I found that words and images in fact build on each other.

Your practice includes many forms of “low brow” materials such as plastic cameras, the iPhone, pinhole cameras, and expired paper. Why are you drawn to these kinds of image making tools and how, if at all, do you think it influences what you make?

Like many people, I began making work with a 35mm camera. In the early 2000s, several friends were using plastic cameras, but at the time I was still using 35mm, searching for the story I wanted to tell. I was not ready to move into the world of medium format. Ironically, I switched to the Holga soon after buying a Hasselblad. Like many Holga users I am drawn to the ethereal, soft-focus images it produces. As someone who wears glasses I feel it matches my natural vision of the world as well as my artistic one. I have never been someone who wants to see every blade of grass in a field, or to have every leaf on a tree in focus.

Why I shoot with a Holga is best summed up in the following comment about Andre Kertesz and the Polaroid camera.

“Kertesz always relied on his own sense of what a camera could or couldn’t do; his past experiences had taught him that he was most successful when he attempted to push a camera beyond its capabilities and embraced its flaws.” (p.24 Andre Kertesz, The Polaroids)

Using pinhole or zone plate, I love the direct relationship of light directed onto the film. Lumen prints take this relationship one step further because the paper is placed directly in the sun.

I am fascinated with the simplicity of these tools. They do indeed influence what images I make, because with pinhole, zone plate, and lumen printing, I am first drawn to the process. I then explore the story I want to tell.

Your influences go beyond artists like Sarah Moon to include poetry and music. Could you please expand on those influences and how they impact your work?

It is interesting how in the image making process, words fill my world and find their way into the poetry I write about the my experience in that particular moment. It is as if words help me see the world, which in turn helps me see with the camera. Music, on the other hand, has an influence during the print process. It influences the tone of my work. With some images, not all, I hear music that translates into words and poetry.

When you began your project “Somewhere Between Here and There,” you started to include poetry with your images. Could you please expand on how the writing cycle works with your pictures? For example, do you write first, photograph first, or is it more circular?

In “Somewhere Between Here and There,” I started out by noting words that came to mind as I sat in the bright noon sun. I saw little point in making work in such hash light, and put my camera aside and words began to fill my mind. These words later formed the basis for many of the poems I wrote. In others instances, after printing the image, I started to write poetry in response to the work before me. In each instance, I think it was a way to describe my experience in a new land. Words and imagery came together to inform each other.

Clearly, the project you made in China, “Another Time and Place,” greatly impacted “Learning Mandarin and Language of Lumens,” your work for the “Memory is a Verb” exhibition. Could you please expand on this influence? Was it a kind of necessary project to get to the Lumen Print project, or something else?

I think the importance of “Another Time and Place,” to “Learning Mandarin and Language of Lumens,” is that it is another part of the process of giving voice to unconscious thoughts, and what I want to say about China.

In this project the printed image become a souvenir, which gave me a connection to a particular time and place. Each is special in its own way and pulls me into the memory of that moment. Souvenirs are but a way of looking and remembering.

In looking at “Learning Mandarin and Language of Lumens,” your work for the “Memory is a Verb” exhibition, you say that the Mandarin characters that you were learning at the time influenced the language of the forms for your Lumen Prints. However, I see landscapes in these prints as much as I see characters. Is that something you intended? If yes, please expand on that influence. If not, then what are your thoughts on how that manifested?

Thank you for your observation about seeing landscapes in this work, although this was not my intent. Perhaps you have tapped into my unconscious because landscapes will certainly be part of my next project, along with characters. In “Learning Mandarin and Language of Lumens,” I am not attempting to replicate Chinese characters in my lumen work, but rather am using the basic concept of the construction of the characters: lines, curves and imagery squares to shape my vision. As I move forward and learn more about the Chinese writing system, I would like to incorporate characters and landscape into collage.

When working with expired paper for your Lumen Prints, the results are somewhat unpredictable. Could you please expand on the element of surprise with this work and how that is a part of your thinking or process?

Making lumen prints is a process of constant experimentation, because the results are variable. Interestingly, it is these surprise elements that have helped me find a voice for this work. Since I started learning Chinese, I have been intrigued with the idea of combining characters and imagery, but did not have a clear idea of how to do this. Early mishaps helped give me a direction forward, because they made me think about the influence of Chinese on my artistic vision.

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

Carolina Baldomá: An Elemental PracticeJanuary 5th, 2026

-

Time Travelers: Photographs from the Gayle Greenhill Collection at MOMADecember 28th, 2025

-

Suzette Dushi: Presences UnseenDecember 27th, 2025

-

Ragne Kristine Sigmond: Portraits of Painterly LightDecember 2nd, 2025