Where Are We Now? In Defense of The Selfie

The selfie is, as the selfie does. My apologies to Forrest Gump.

I live with my family on an old, inconveniently distanced farm place in middle Georgia, USA, a couple of hours drive from Atlanta. We are backwoods to the backwoods. We call the place “3 Cent Farm” (long story). I mention the name, because if you’re on Instagram, you can see a lot about the place at #3CentFarm. We’ve had many creatives, especially photographers, visit over the years and the hundreds of photos are starting to pile up. I stack up more than anyone of course. What can I say; the place is pretty photogenic, and I always have a phone in my pocket. But, you’ll see only one selfie there. I have been a Danny-downer on the genre, but I am hoping to change that going forward and here’s why. I finally get that as photographers, if we are curious and fascinated by this world and the place of humanity in it, why wouldn’t we want to turn that attention towards ourselves and use the technology and forms of our moment? As usual, finding a meaningful experience with this form of expression is a matter of intention.

This week I was delighted to have a visit here from my long-time teacher, collaborator, and friend, Stephen Shore. As he was getting ready to drive back to Atlanta, I realized I hadn’t taken a photograph with him to memorialize our visit together. So, we stopped on the back porch, and I took a couple of selfies. As I took the pictures, I was reminded that, relatively speaking, I do not take many selfies. I was ‘hating on’ selfies, even though I’ve always had a love for portraiture and especially self-portraits — just not my own. And to be clear, a self-portrait and a selfie are siblings but not the same thing. Here are a couple of self-portraits I admire. And interestingly the Leyster oil painting from 1630 has an energy leaning into the selfie space more than the highly structured and considered Shore self-portrait from the 1970s.

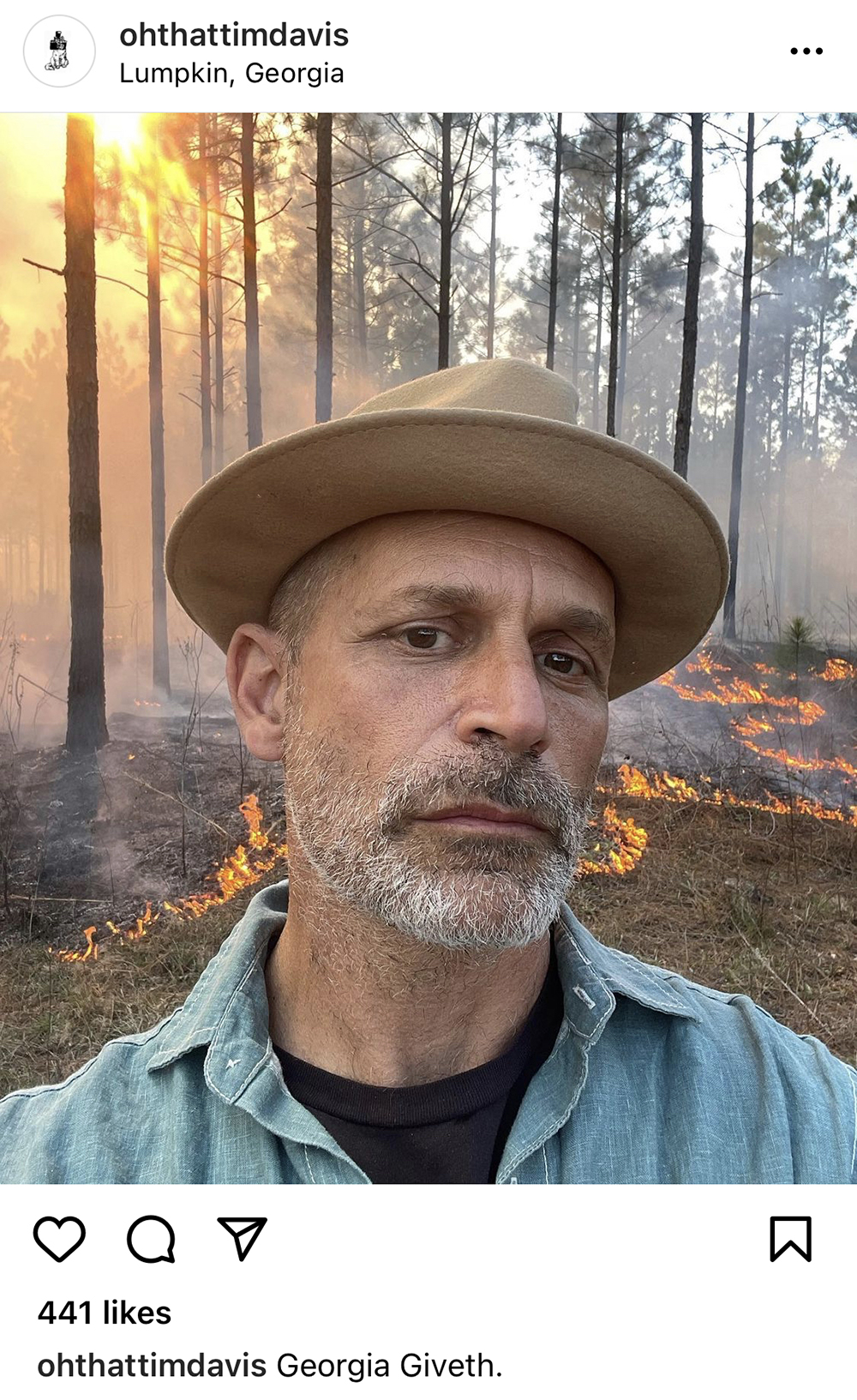

Somehow, the selfie, a creature of the smartphone and social platform world, through its abuse by excess became, if not loathsome to me, something…“meh”. It came to exist for me in its own little subcategory of popular photography that I gave less weight or love to than the old school self-portrait forms. Over the years, as more attention was given to the genre beyond its boom inside of social media, I shied away even more. Atlanta’s Original Selfie Museum is down the block from my Fall Line Press studio and gallery in the Castleberry Hill Arts district, and I haven’t stuck my head in the door yet. (It is not really a museum; they are a photography studio dedicated to supporting you in putting your best selfie forward). Cute cat pictures have had more appeal for me. But, I want to change that for myself. I want to create an attitude adjustment if you will. Here, Tim Davis offers a nice palate-cleansing selfie from his Instagram feed pointing to the selfie’s creative possibilities.

The well-documented rise of the selfie has been driven by the ubiquity and ease of the phone camera coupled with billions of social media accounts lusting after images to share. And what is better to share than an image of one’s self scratching an itch to be seen, perhaps a desire to ‘be known’? And not just “known” but to be known and positioned in a certain way. It is the ultimate visual positioning of the self. It is often a kind of “look! here I am” and too often coupled with a “ain’t I cool”. We are after all only too human. Maybe it is that self-promotional element of selfie-dom that has put me off. And yet there are so many selfies that don’t contain a drop of that and reveal so beautifully just the who, what, when, where of a human life — often achieving the very art of the lyrical document that most photographers strive for. Here is one of my friend, the great designer Margaux Fraisse with her mother Brigitte.

My phone’s photo iCloud archive has over 130,000 phone photos stretching back about eight years and only a couple hundred of those are “selfies”. And out of more than 3,500 Instagram posts, I have only a couple of selfies. This seems wildly out of step with my fellow Instagrammers who have hash-tagged over 465 million selfies thus far. As Kim Beil points out in her superb treatise on popular photography, Good Pictures, 2013 was a pivotal year for the selfie with a Time magazine cover story on the topic and Oxford Dictionary’s selection of “selfie” as the new word of the year.

So, I am asking myself why do I shy away from what is probably the most beloved genre inside of modern popular photography? It is certainly not a lack of self-involvement. I am as self-centered, vain even, as anyone I know — I can’t seem to get enough of myself. And maybe that points to one of my problems. When I think about extending my arm and pointing the camera back at myself, I become uncomfortable. I am self-critical, and because I have some specialized ideas about photography, maybe I freeze up or worse — ham it up. Whatever, I’m just not at ease with my own gaze in my own direction. But, it shouldn’t be this way, and I’m writing here like a prisoner with a spoon wanting to dig my way out to the freedom of fully self-expressed selfie-love. A couple of first spoonfuls.

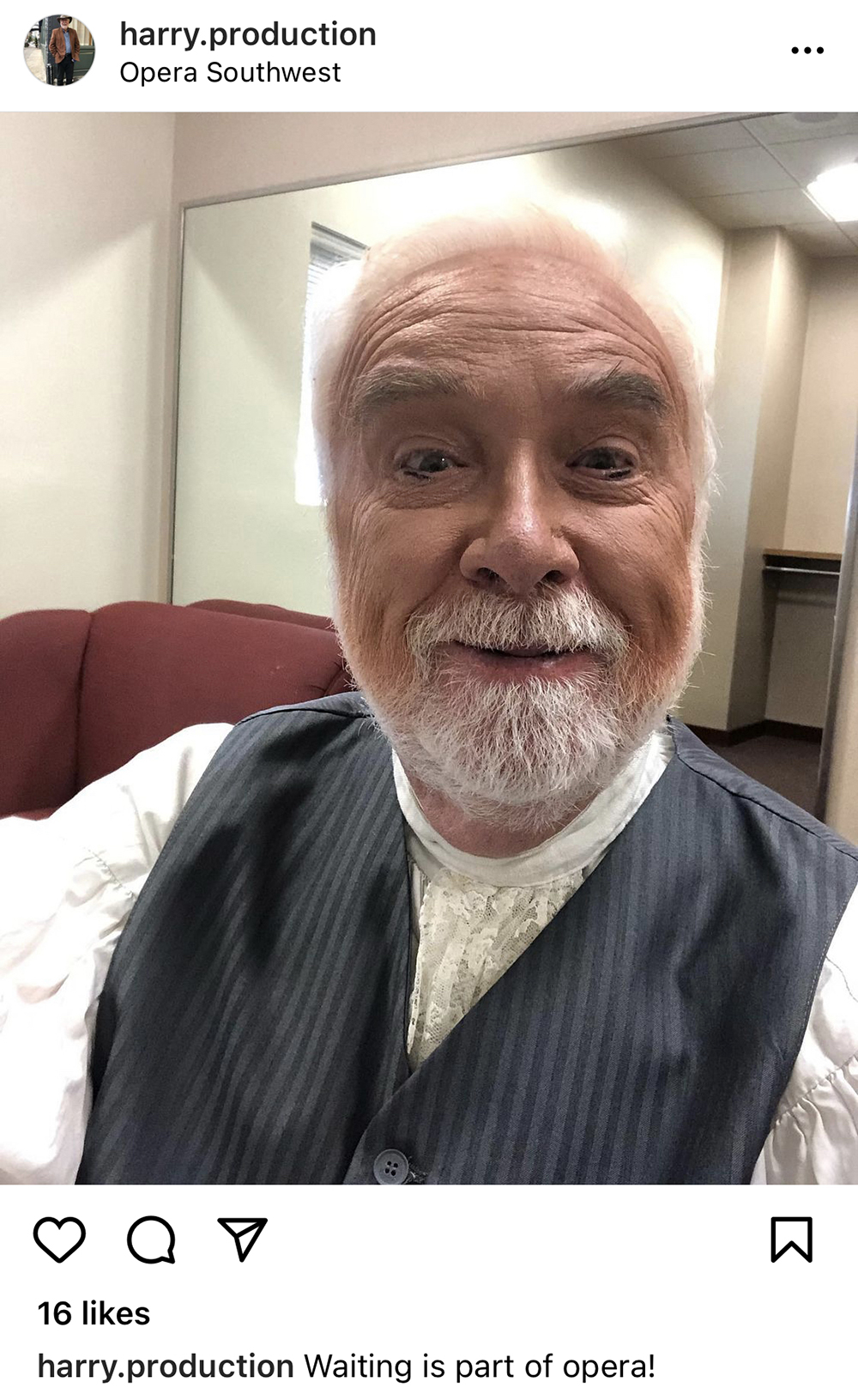

The earliest certain self-portrait I could find was by the artist Bak, chief sculptor to the Egyptian pharaoh Akhenaten. Dating from circa 1353 BC, it has the feel of a stone selfie. The work portrays the artist and his wife and while they are standing stiff legged and looking straight ahead. There is a surprising degree of idiosyncratic casualness and detail in their features. We are given his very round belly and her wide hips and long slender waist. Their portrayal seems almost candid compared to what I expect to see with Egyptian figuration. These are real people. It’s like they are saying, “hey look, here we are.” And that’s the essence of a selfie — “hey look, it’s Stephen and Bill,” we’re on the back porch, or at the ball game, venue, or event — here we are together. Or if solo, “here I am, right here, in the bathroom, on a horse, waiting for my opera appearance, whatever.” The selfie functions as a kind of certificate of being and proof of attendance. At bottom, that function is a memorial one — a personal souvenir. And that’s nothing to sneeze at. As I surveyed my paltry selfie collection I found one I had forgotten of the last time I was together with both my mother and my father. My father who is now in his 90s, and my mother who passed away last year both developed dementia and lived apart for many years.

And that memorializing purpose can be just as touching and valued among friends in less dramatic ways. Here’s my friend the singer and performing artist Harry Musselwhite at the opera. I was delighted when it showed up on my Instagram feed this week.

And as Bak shows us — with a good selfie — you’ve got a shot at a kind of near immortality. 3,375 years ago is not that long in the grand scheme of things you may say. Yet, while it’s true the earth formed around four and a half billion years ago, it appears the Homo sapiens‘ experience has only endured thus far for about 300,000. In a billion years or so, Bak will look completely OG. And so will all those 465 million Instagram selfies.

And beyond documenting and preserving the moment, there are perhaps deeper possibilities.

There is a solid argument made that an even earlier selfie was happening with the Paleolithic fertility carvings. The most famous of these, the Venus of Willendorf, dates to approximately 30,000 BC and if it is indeed a self-portrait it pushes Bak towards us and into newbie land. As Emily Pothast points out with her wonderful essay on female self-portraits, “A Feminist History of Self-Portraiture”, there is strong academic support for the theory of fertility carvings as self-portraits. Interpretation of Paleolithic art is as problematic as Insta art. But, doesn’t it seem possible that for 30,000 years an element in the selfie DNA is simply the wonder of being; being alive in this body, in this place, at this time…perhaps with this person or alone? Just being.

I am wanting to look at selfies in that light — the wonder of just being — and I’m trying to shove aside the less compelling intentions and motives of influencers; the positioning of the self and the myriad of narcissistic use cases. And I’m doing this while trying not to be judgmental, because I am also all too human. It seems there are some powerful and traditional foundations that selfie’s enjoy. The joy of self-examination as a being — here and now.

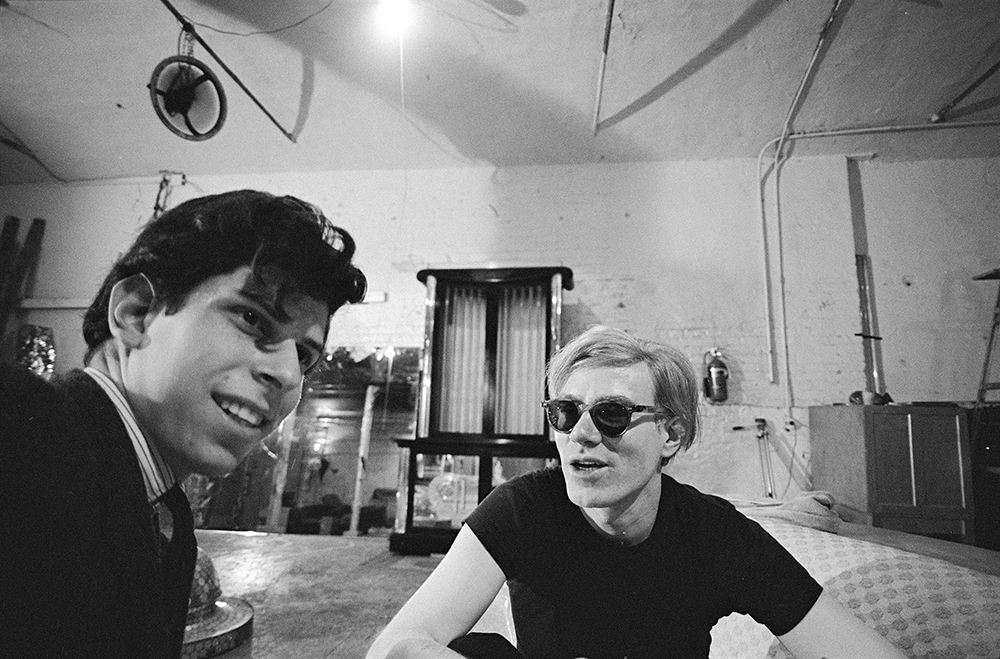

Here’s a selfie of a young Stephen Shore with Andy Warhol at The Factory in 1966. Shore is obviously thrilled to be in his company and preserving that ‘being here now’ moment. This selfie is included in his recently published memoir with MACK books, Modern Instances. It serves him as a personal memento, and it supplies the art and photography world with an historical record. It exudes the feeling of a young apprentice happy in the presence of the maestro.

There is a final base to point to in defense of the selfie. It may be useful as a powerful creative genre. As Kim Beil points out in Good Pictures, photography is a medium that revels in recirculating worn out technologies and tropes that get unearthed and repurposed for new expressions. Shore’s beautiful 8×10 self-portrait above comes from his early and seminal project Uncommon Places. In this work, there is an obvious artistic intentionality, and while it has the highly refined, yet casual “just the facts ma’am” gestalt that was exploratory for that time in the 70s, it lacks the shape, tone and the ‘being here with Andy’ energy of the previous photo that truly represents the selfie code. The Tim Davis’ selfie in the fire is intentionally using the now increasingly decoded genre of the selfie to turn in onto itself for a satirical and creative use.

Here’s another very early Shore “selfie” where he was experimenting with a Mickey Mouse camera. The free wheeling spirit of the genre is right on the surface of it as was the ‘daring’ use of color. Here again, we see the DNA of what we now know as the selfie, but it gets its energy from the other exploratory elements of the Mick-a-matic and the transgression of using ‘the wrong’ materials to gesture toward art photography knowingly.

I will close with a couple of self-portraits that make it difficult to apply the word “selfie” to and yet they have nearly all the elements of a selfie – just not the gestalt. They both have similar means and certain formal characteristics of the form, and yet the subject they’re connecting with is outside the usual energy and depth we expect from the genre. I share them because they are moving, and because they are beautiful as truth is always and because I think they transcend labels and remind us that as helpful as it is to have handles for the images we speak about — there are limits to what words can contain.

The first is a self-portrait my friend the artist Tanya Marcuse took of herself wearing a face-shield as she was visiting her mother at the end of her mother’s life. The shield was a required precaution to allow her to visit her mother. Marcuse has shared on Instagram several very moving photographs from those last visits with her mother. Her willingness to make her passage there available to others was and is generous and is a powerful use of photography in service of human understanding and healing. These images were created and shared via the phone camera and a social media platform – the life blood of the selfie. And yet it does not resonate for me as a selfie.

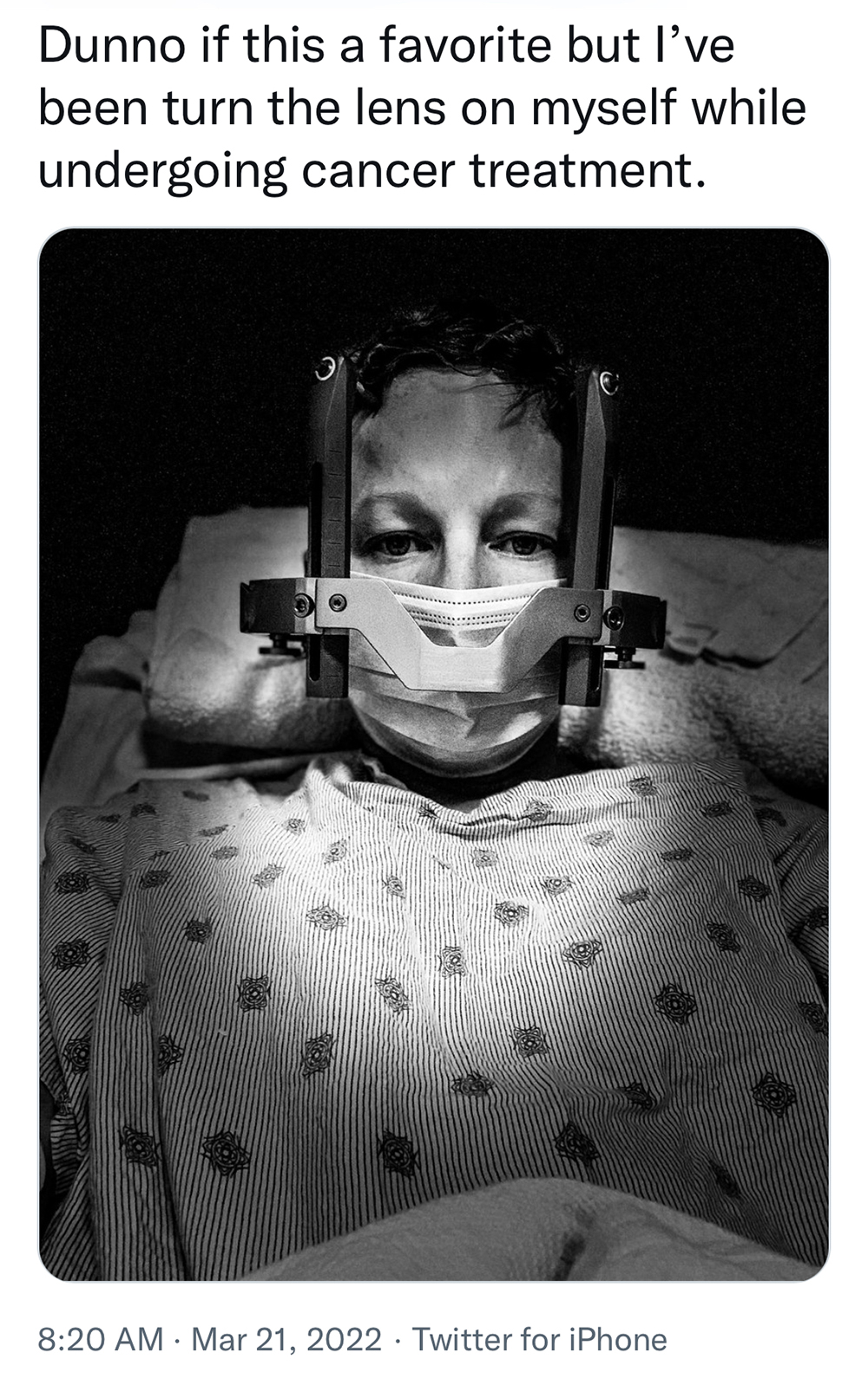

Finally, I queried the Twitterverse this morning about this topic and received the following amazing photograph from photographer and writer Christy Lorio who has been documenting her course of treatment for cancer for the past two years. As she stated to me, “I use my phone because I don’t want to alter the experience by bringing a “real camera” with me to my medical appointments and procedures.” The image is as powerful as any I’ve ever seen in the realm of what we are dealing with as mortal human beings running the gauntlet and arrows of life; illness, suffering, grappling and healing. Turning the intimate phone camera on ourselves intentionally and with the courage of sharing our lives authentically is perhaps the greatest use of the self-gazing we call ‘selfies’ and self-portraits.

William Boling is an artist, writer, and photographer. In 2012, Boling founded Fall Line Press, an independent publishing house for photo and art books based in Atlanta, Georgia. Boling lives with his family on a small farm near Milledgeville, Georgia where he specializes in near misses. Read more of his writing and connect with him @wboling, @patientletters and through www.falllinepress.com. For more in-depth writing on photography, please follow patient.letters@substack.com

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

Richard Koenig: Field Notes: View from a Hotel WindowFebruary 13th, 2026

-

Beyond the Photograph: Editioning Photographic WorkJanuary 24th, 2026

-

The Next Generation and the Future of PhotographyDecember 31st, 2025

-

Spotlight on the Photographic Arts Council Los AngelesNovember 23rd, 2025

-

100 Years of the Photobooth: Celebrating Vintage Analog PhotoboothsNovember 12th, 2025