Earth Week: Nick Brandt: The Day May Break

This week’s bodies of work are linked by this thematic lens: making the often-invisible nature of the global climate and the ecological crisis more visible using conceptual, lens-based art techniques. Each body of work speaks to a different aspect of the climate and ecological crisis: sea level rise; coral bleaching; habitat loss and environmental destruction; deforestation; melting glaciers; plastic pollution.

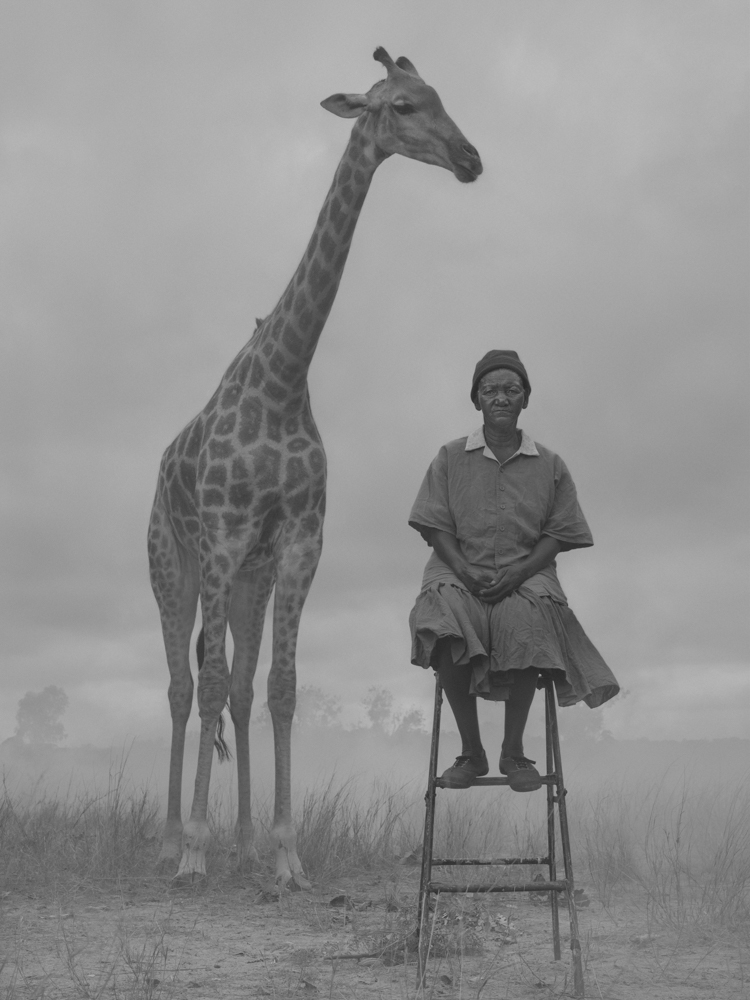

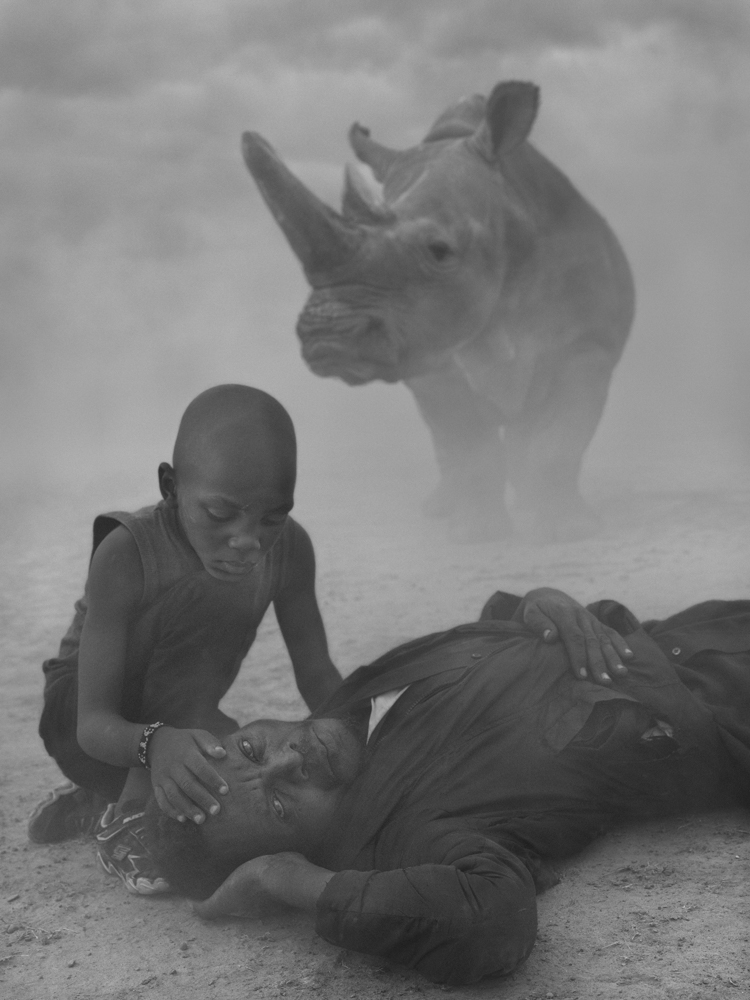

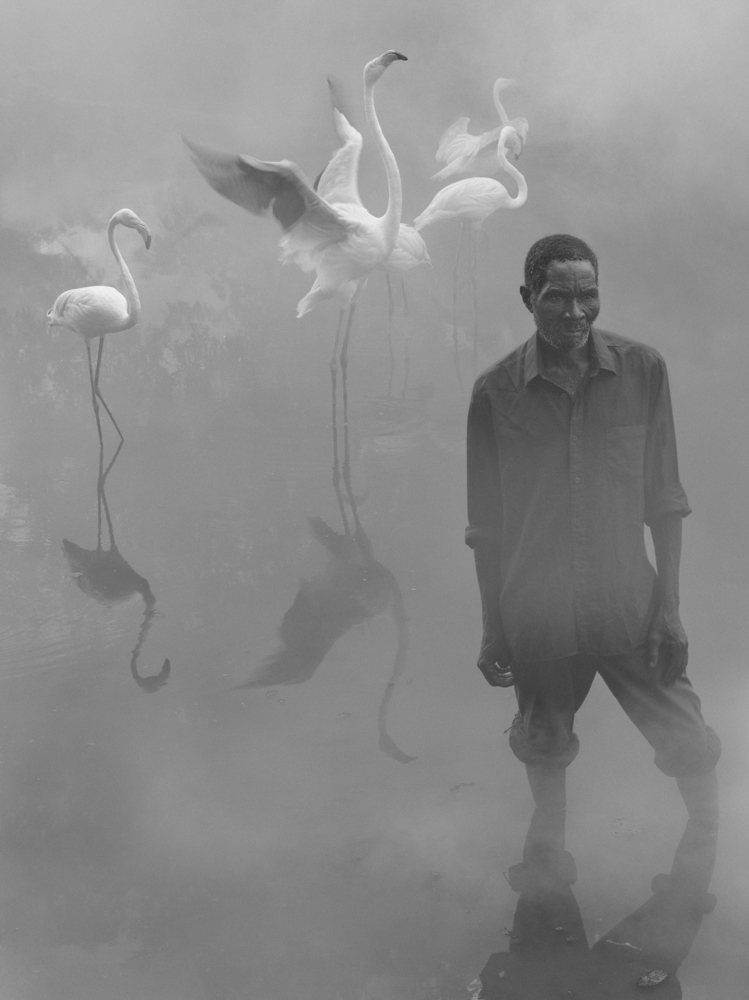

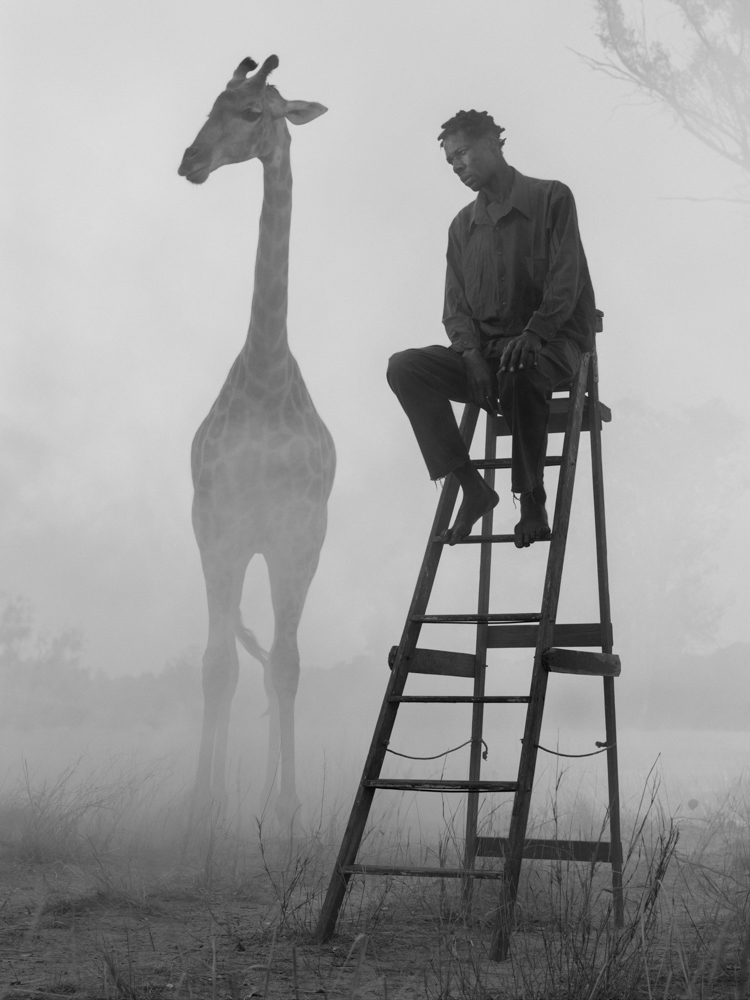

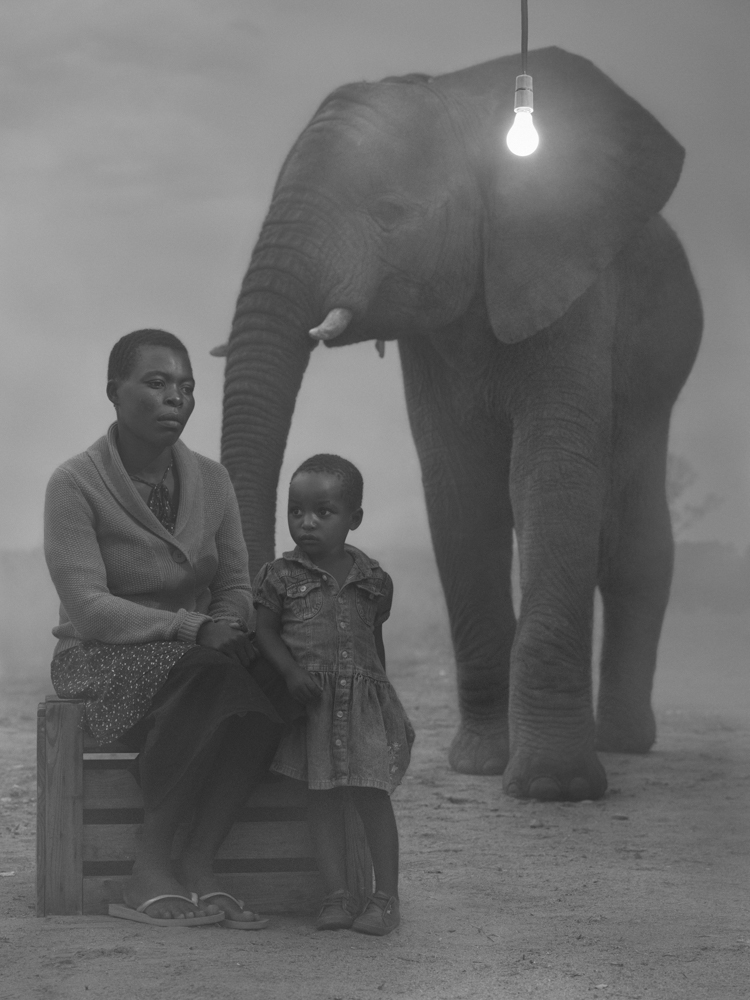

Photographed in Zimbabwe and Kenya in late 2020, The Day May Break is the first part of a global series by photographer Nick Brandt, portraying people and animals that have been impacted by environmental degradation and destruction. The people in these photographs have all been badly affected by climate change—some displaced by cyclones that destroyed their homes, others such as farmers displaced and impoverished by years-long droughts. Photographed at five sanctuaries/conservancies, the animals are almost all long-term rescues, victims of everything from the poaching of their parents to habitat destruction and poisoning. These animals can never be released back into the wild. As a result, they are habituated, and it was safe for human strangers to be close to them and photographed in the same frame at the same time. The fog on location is the unifying visual motif, conveying the sense of a once-recognizable world now fading from view. However, despite their respective losses, these people and animals have survived, and therein lies possibility and hope. The series continues in 2022 in South America.

Brandt has also released the mongraph, The Day May Break, published by Hatje Cantz Verlag, in 2021 and it is available through photoeye Books.

The themes in Nick Brandt’s photographic series always relate to the destructive impact that humankind is having on both the natural world and now humans themselves too. This began with his trilogy On This Earth (2005), A Shadow Falls (2009), Across the Ravaged Land (2013). The escalating destruction, and its impact on both the wild animals and the rural poor led to the creation of Inherit the Dust (2016) and This Empty World. (2019). The most recent work was The Day May Break (2021), the first part of a global series. Brandt has had multiple solo exhibitions in museums and galleries worldwide. In 2010, Brandt co-founded Big Life Foundation, a nonprofit that now protects 1.6 million acres of the Amboseli/Kilimanjaro ecosystem of Kenya and Tanzania.

Follow Nick Brandt on instagram: @nickbrandtphotography

Ali and Fatuma Mohamed

Zimbabwe has the second highest population in Africa, perhaps 65,000 as of 2020. However, since 1965, the country has engaged in the periodic culling of elephant herds, families, and individuals, due to what is regarded as an excess population.

Once upon a time, there would have been no such thing as an “excess population,” because there would have been enough land for them to roam and migrate. But with habitat loss and destruction, and human encroachment, this forces elephants into the remaining uninhabited areas, resulting in severely damaged woodlands from overgrazing. And then the culling begins.

Teresa and Samuel used to live and farm in the central Highlands of Kenya. But in 2016, after three months of constant rain, landslides from the flooding covered and destroyed their house and killed their livestock.

They were forced to move to Nanyuki, where life has been a real struggle, a hustle, finding menial jobs. Samuel says “I don’t even like to remember where we lived before – it’s too upsetting.”

With climate change, the situation becomes much worse, as vegetation and woodland dies off and burns, and humans and wild animals search for what remains.

Bupa and another elephant, Jackie, were 8 or 9 years old in 1989, when they were rescued from a culling project in Zimbabwe by the owner of Ol Jogi Conservancy in Kenya. Their parents would have been killed.

Bupa and Jackie bred at Ol Jogi and had a daughter, Meisha. Jackie died from a viral infection in 2019.

Halima’s husband left her, and so she and her children had to move south to Nanyuki. She is now forced to do menial jobs to raise her kids.

Kudu are declining in population across areas of sub-Saharan Africa due to illegal bushmeat poaching, habitat loss and deforestation.

©Nick Brandt, Harriet and people in fog, Zimbabwe, 2020, Courtesy of Fahey Klein Gallery, Los Angeles

Giant eagle owls are actually widespread across sub-Saharan Africa, although perhaps declining in rural areas.

The southern African giraffe, of which, as of 2021, there are less than 30,000 remaining in the wild, is listed as threatened. Across the continent of Africa, there are barely more than 100,000.

Shockingly, in Zimbabwe, giraffes are not a protected species; hunting, the removal of animals and animal products from a safari area, as well as the sale of animals and animal products is permitted.

James used to own a five-acre farm in central Kenya. He was successful and “life was good.” But years of long droughts made making a living harder and harder, until 2015, when bankrupt, he was forced to move with his wife and child and look for a job of any kind. This formerly proud, independent farmer has been reduced by climate change to being a casual laborer in the county market.

Fatu is one of the last two northern white rhinos in the world. When Fatu dies, the species will be extinct. Once upon a time, the northern white rhino’s range extended through central Africa. But decades of poaching have taken its grim toll.

Fatu was born in captivity, and had been living, along with two males, in Dvůr Králové Zoo in the Czech Republic. In 2009, the four rhinos were moved to Ol Pejeta Conservancy in Kenya in the hope that they would have a better chance of breeding. Sadly it never worked out. Sudan, the last male, died in 2018.

So now, complex in vitro fertilization procedures—never before attempted in rhinos—are conducted several times each year in a final attempt to keep the species from going extinct.

In the meantime, Ol Pejeta has around-the-clock armed security for Fatu.

©Nick Brandt, Luckness, Winnie and Kura, Zimbabwe, 2020, Courtesy of Fahey Klein Gallery, Los Angeles

Currently, Luckness and her children are living in a makeshift camp for displaced people affected by the cyclone.

Cyclone Idai was a terrifying harbinger of what climate change will bring in the coming years: more frequent high-intensity storms. And with that comes, of course, more destruction.

Lesser flamingos are declining as the number of breeding sites for them diminish.

©Nick Brandt, Regina, Jack, Levi and Diesel, Zimbabwe, 2020, Courtesy of Fahey Klein Gallery, Los Angeles

Diesel and Levi’s mother was killed by a farmer protecting his livestock. They came to Wild Is Life when they were about six weeks old, full of ringworm and very thin. Wild Is Life managed to pull them through, but because they were so young and so domesticated, they were poor candidates for release.

14 years old when photographed, they have had healthy lives with daily walks. In March 2021, Diesel died aged 15, a grand old age for a cheetah, whose average life span is 10-12 years.

The current situation for cheetahs in Africa is stark: driven out of over 90% of their historic range, the population across the continent is down to less than just 7,000 in 2021. At the current rate of decline, cheetahs are heading toward extinction.

As ever, habitat loss is one of the main reasons. With that also comes the decline and disappearance of the species that they prey on, as those are killed by humans for bushmeat. Even in protected areas, cheetahs are in decline, partly because the animals need room to roam.

Richard feels that the reduction in rainfall has been caused not just by climate change, but also by the clearing of forests for the production and curing of tobacco, which has left vast stretches of forests in the area barren.

Michael O. Snyder is a photographer and filmmaker who uses his combined knowledge of visual storytelling and conservation to create narratives that drive social impact. Through his production company, Interdependent Pictures, he has directed films in the Arctic, the Amazon, the Himalaya, and East Africa. His photojournalism work has been featured by outlets such as National Geographic, The Guardian, and The Washington Post. He is a Portrait of Humanity Award Winner, a Society of Environmental Journalists Member, a Pulitzer Center Grantee, and a recent delegate to the United National Climate Conference. He holds an MSc in Environmental Sustainability from the University of Edinburgh, Scotland and a BSc from Dickinson College, Pennsylvania. He lives in the shadow of the Blue Ridge Mountains of Central Virginia.

Follow Michael O. Snyder on Instagram: @michaelosnyder

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

Rachel Nixon: Art + History Competition Honorable MentionApril 3rd, 2025

-

Photography Educator: Frank LopezMarch 21st, 2025

-

TOP #20 Expanded CyanotypesMarch 18th, 2025

-

Re-molding the Self: Clay Feet, Photographs by Rebecca HorneMarch 5th, 2025

-

Nancy Kaye: Too Many GunshotsMarch 4th, 2025