Interdisciplinary Approaches in Photography: Addison Brown

This week, all of the artists that I am featuring take photography beyond what it is or what it is perceived to be, to what it can be. There are a wide range of themes such as family, culture, loss, history, memories, biblical stories, mythology, film and community among others. For all of these artists, the photograph is the starting point, not the end result. Beyond photography, their approaches incorporate painting, stitching, alternative processes, object making, sculpture, installation and even community engagement. Each of them employ process and content that creates a uniquely personal style of photography that demonstrates extraordinary vision.

I met Addison Brown back in 2014, three days before we began grad school at East Carolina University. The grad students and faculty took a kayaking trip in Washington, NC. Addison was out in front of everyone on his kayak, and I was trailing everyone. I remember wanting to not like him because we were polar opposites, and in some ways, we still are. He is 17 years younger than I am; he is intense, while I am really laid back. We even make work differently. None of that mattered because we bonded over a desire to make art and to learn. It did not take us long to become friends however, and I don’t think either of us would have survived grad school without each other’s support. We pushed each other to another level during those three years, and we still try to talk weekly, encouraging and inspiring each other.

Addison has the ability to read about something and decide to immediately try it himself. If he fails at first, his precision will not allow him to give up. This determination was proven when he made a mutoscope, which is a hand crank device that shows a short film by flipping through images on cards. Addison made 1051 cards, each with a different image. He had no instructions and probably remade the device three or four times before he constructed the finished product. Addison’s work involves creating and photographing himself as archetypical characters inspired by films. It is really fun to observe Addison’s at work because he doesn’t break character. He very easily could have been an actor, but instead his characters become a part of his art-making process.

Addison Brown is a photography-based artist currently living in Huntsville, Alabama. He received his BA in photography at the University of Alabama Huntsville in 2012 and a MFA in photography at East Carolina University in 2017. His interests in history, photography and cinema often blend together with the use of historic photographic processes concerned with dramatic narrative, identity and confrontation. Addison’s work takes the form of one-of-a-kind, unique photographic objects that typically employ techniques in woodcraft and metalworking and have been exhibited nationally and internationally. Addison currently teaches at the University of Alabama Huntsville.

Follow Addison Brown on Instagram: @addison_j_brown

©Addison Brown, Legerdemain, 2017, Artist-made Mutoscope, 1051 photographs, Brass, Steel, Wood, 34.5” x 13.4” x 31”

My fascination with film has always played a significant role in both the questions and revelations that inspire me as a maker. As a young moviegoer I remember the occasions where I wasn’t enthralled with the movie I was watching but rather a singular dust beam of light, flickering in accordance with the screen. As I traced the light back to its origin, it disappeared into a small rectangle in a black wall. Perhaps when the movie wasn’t enough to hold my interest, the production of the image and its mystery did. The films that capture my full attention are those that leave resolve in the hands of the viewer. This realization has informed my creative life. I show but do not tell. By using elements of performance and often requiring an action from the viewer, my work explores themes of identity, nostalgia and confrontation. I am moved by the photograph’s ability to preserve mystery and I recognize this quality as the ultimate inspiration for me as a maker. – Addison Brown

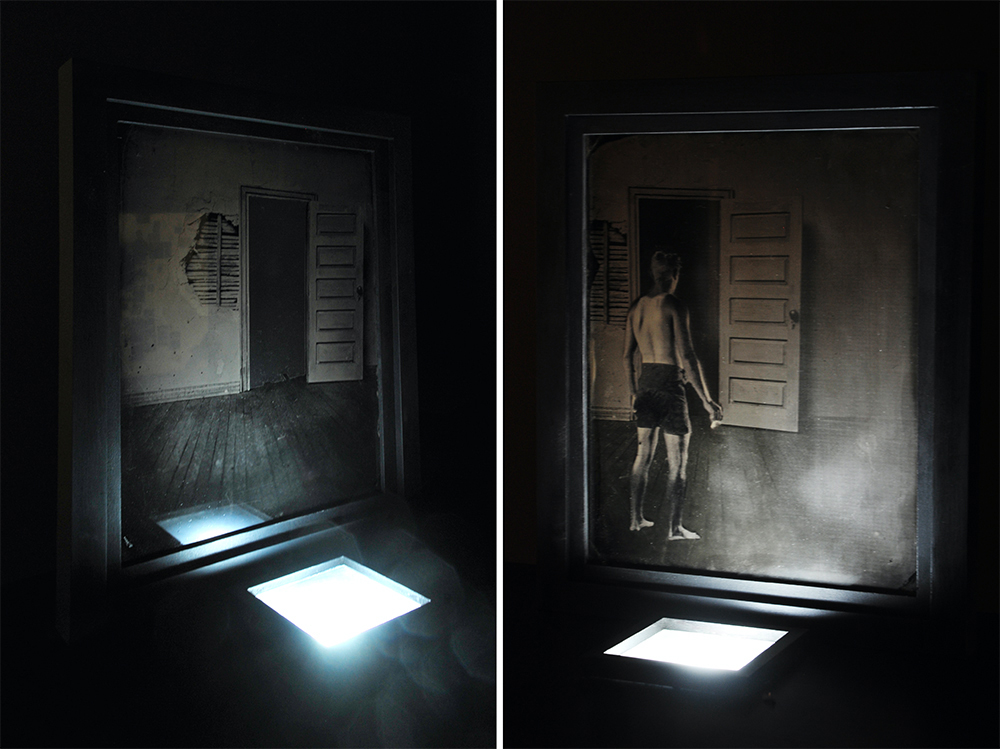

©Addison Brown, Visitation, 2017-2019, Layered Ambrotypes, Steel, Vinyl, Wood, 8.25” x 9.25” x 11.5”

Talk about how and why you were doing characters as early as high school and how they became a part of your photographic process?

Recently, I applied to my high school alumni group on Facebook. I wasn’t accepted because they didn’t know who I was. It got me thinking of the ways I contributed this and I briefly felt proud of my anonymity in the overwhelmingly awkward period of high school (and beyond). I performed as Eddie Perkins, whose social ineptitude is far beyond my own; this is no small feat, mind you. Students, teachers and administration were all subject to the performance. The vice principal of the school was the poorest sport, although, I must admit the third time of successively dropping my books in front of him was pushing my luck. I never photographed Eddie Perkins until I was in college. My breakthrough photographs of the character were in an abandoned school and I felt a lot of support from my mentor José Betancourt at the University of Alabama Huntsville. Later on while pursuing my masters at East Carolina University, you (Greg Banks) and the faculty gave me the much needed encouragement to pursue it again. It became apparent that I enjoyed making in this way and that choosing the process that feels natural is crucially important to the development of a body of work. The still image allows me to work by myself and smooth over my incompetencies as an actor. Selling a performance in a singular frame is different from selling it in hundreds of thousands of frames.

©Addison Brown, Attic, 2018, Artist-made Stereoscope, Layered Ambrotypes, Glass, Mirrored Ambrotype, Wood, 68” x 18” x 40”

Film and history inspire many of your images but also the characters that you create. You could appropriate the characters but you choose to become the characters. What is the process of becoming a new character and why it’s important to participate on both sides of the camera?

I am a nostalgic type of person that believes that history is always deserving of more thought, especially the more obscure bits. The discovery of various technologies throughout time is an endless source of amazement. The history of photography is full of incremental and revolutionary improvements in its technology and practice in a relatively short amount of time. It is never boring for me to seek out the small blips on the radar of photography history and to attempt to imagine it differently. I am immensely inspired by practical effects in film-making. I am interested in the dichotomy of enjoying both the trick and its method in cinema. I intend for my work to provide a similar experience. It’s a basic observation to determine that the characters are all the same person in my work. It’s also simple to understand the construction of layered glass plates. Neither of these contrivances are doing a great job at tricking anyone, especially by modern standards. To what extent is the viewer willing to disregard the method in order to immerse themselves into fiction? The more I researched into film history the more I began to recognize that there are limits to the suspension of disbelief. These limits establish the importance of being on both sides of the camera in my practice.

©Addison Brown, Installation view of Dramatis Personae featuring 8” diameter Ambrotypes with corresponding wooden silhouettes. Stands are made of copper, steel and wood.

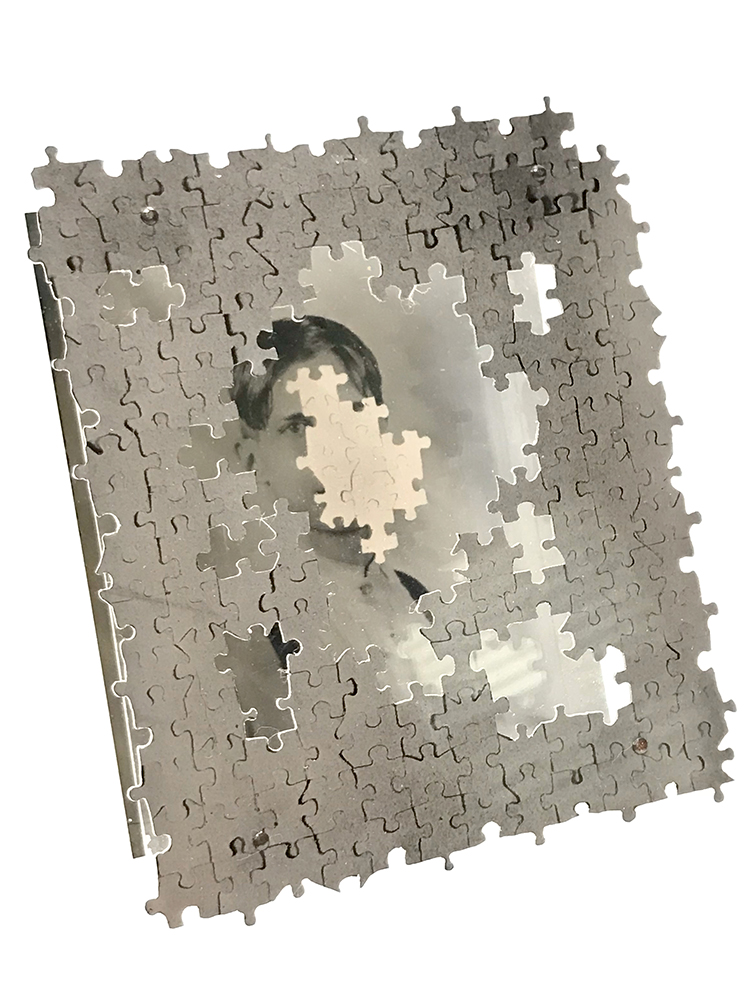

For you the photograph is only part of your process. Typically, the photograph becomes an object inspired by photographic devices from the 1800’s, or you layer several ambrotypes to create one image. Why is it important for the work to go beyond the print or plate?

Even in the early days of photography, there were several unique instruments and methods of displaying a photograph. Objects and instruments that require interaction of the viewer are especially inspirational. I want to make things I don’t know how to make which makes it less common for me to commit to the simplest form of any idea. I have to feel challenged in the content and production of everything I make which also extends to viewership as well. The average time that a person spends looking at a photograph is incredibly short. Different methods of interaction of a photograph creates a unique experience. Content-wise, I incorporate subtle details to reward the commitment of patient viewership. Witnessing viewer involvement is something that will never grow old.

©Addison Brown, Portrait of Eddie Perkins, 2015, Collodion Positives on Aluminum and Acrylic, Copper, 4” x 4.75” x 1.25”

You decided to make a mutoscope in graduate school. You remade parts over and over and gained skills in woodworking and metals. What was it like to have graduating hinge on whether this device worked right up until the exhibition date?

I made Legerdemain as a way to emphasize and celebrate the viewer’s role in the importation of fiction to reality. In the case of the Mutoscope, an early accessible form of cinema, I love the physical involvement of cranking a giant flip book to produce a motion picture. The film of Legerdemain depicts myself as a viewer in front of a projection screen, watching various characters from the Suspension of Disbelief series. The camera trucks and pans in a circular fashion around me and to the back of the projection screen. As the camera comes out from behind the screen, the character and I have swapped places – the character in the chair and I on the screen. It is a seamless loop that utilizes three different characters. It’s my love letter to the art of cinema and photography and the capacity of both mediums to transport us. As much as it would be impressive for me to say that I was confident it would all work out – I wasn’t. Even as the scrap pile grew proportionately to self-doubt, I knew I’d grown in such a big way. I can overthink something until I don’t start at all and I had already grown from that level. I am proud of that. Most of all, I had an incredible support system during that time that gave me the courage to finish. Serious sleep deprivation contributed to the delay of acknowledging the finality of it all. At one point, I woke up to a smoke-lined ceiling and the fire alarm in my apartment. In a delirious state, I determined it was the furnace, pulled the fire alarm out of the ceiling and switched off the main circuit breaker, opened the sliding porch door and my window and went back to sleep. It was 38° in my apartment when I woke up to seeing my own breath. Management was stupefied when I nonchalantly told them there was a possible fire in my apartment early that morning and I placed the fire alarm on my clothes dryer. Oh, and I made sure to request that the technician wear boot covers when entering to keep mud off of the carpets because priorities, you know? Nothing mattered more than making art and finishing it. The feelings caught up at the end it I still regard it as the best time of my life. To this day I feel honored and humbled by the time and energy everyone invested in me.

©Addison Brown, Installation view of Dramatis Personae featuring 8” diameter Ambrotypes with corresponding wooden silhouettes. Stands are made of copper, steel and wood.

©Addison Brown, Clyde Jamison Basilus III (from Dramatis Personae), 2017, Ambrotype, Copper, Steel, Wood, 14” x 14”x 62”

The thing in your head is the thing you are trying to achieve. If you do not achieve it, you see that as failure. You will continue to remake the image or object over and over until you achieve your vision. Can you talk about how this struggle has made you a much better artist but also hindered you as an artist?

Truthfully, I feel that it is more of a hindrance to be a perfectionist. Not once have I ever made anything perfect and, ultimately, no one will ever know how much thought I put into anything. I put a lot of pressure on defining my best effort. The slippery slope is moderating expectations of myself while my personal best changes with what I am learning. The challenge of learning through making is a way to quell the negative perfectionist tendencies. It has become quite valuable to start the hard stuff, build skills and finish the fight. I have a fundamental respect for anyone that makes anything simply because I am aware what it takes me to start anything. The flash in the pan is when I can best the hypercritical restraints in my process. The best thing I have ever done for myself in combating perfectionism is to teach. I am acutely aware of how perfectionism can stifle the creative process and when I began to identify traits in students, I knew that I must be able to provide support for them in ways I have been previously unsuccessful. I need them to know that it won’t be the last thing that they ever make. I need them to know that the work must be made specifically to build confidence that they can finish. The problem with doing all the thinking on the front end is that it’s bound to be based on former experience. It can’t possibly account for one’s future. The detriment of the artist is not bad ideas. The detriment of the artist is idle hands. Thinking never built anything. I’d like to thank all the students and teachers that inspire me and make me want to be a better as an artist, person and teacher.

Greg Banks is a photo-based artist and lecturer at Appalachian State University. He received his MFA in photography from East Carolina University in May 2017. He received a B.A. in photography and a B.A. in fine art from Virginia Intermont College in 1998. Greg combines everything from IPhone images to historic 19th century processes, gelatin silver printing, painting and digital printing. His current creative practice investigates family, folklore, memories, magic, history and religion in Appalachia.

Follow Greg Banks on Instagram: @gregbanksphoto

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

Binh Danh: Belonging in the National ParkMarch 4th, 2026

-

Vaune Trachman: Now IS AlwaysMarch 3rd, 2026

-

Amy Friend: FirelightFebruary 25th, 2026

-

Jonathan Silbert: InsightsFebruary 19th, 2026

-

Olga Fried: Intangible EncountersFebruary 18th, 2026