Interdisciplinary Approaches in Photography: Stephanie J. Woods

©Stephanie J. Woods, My Brother and Me, 2020, 50” X 40” Family photo transferred onto hand-cut and sewn quilt tops, textile foil, heat transfer vinyl, Sharpe, textile paint, and polished furniture vinyl.

This week, all of the artists that I am featuring take photography beyond what it is or what it is perceived to be, to what it can be. There are a wide range of themes such as family, culture, loss, history, memories, biblical stories, mythology, film and community among others. For all of these artists, the photograph is the starting point, not the end result. Beyond photography, their approaches incorporate painting, stitching, alternative processes, object making, sculpture, installation and even community engagement. Each of them employ process and content that creates a uniquely personal style of photography that demonstrates extraordinary vision.

The art of Stephanie J. Woods intrigued me at first because of the way she uses photography in an interesting multidisciplinary way. The first pieces I saw were from the series A Radiant Revolution, which is a series of performative portraits of figures with t-shirts on the heads, shot from behind. Upside down type reads my black is beautiful, strong black girl, and black girl magic. The framing of the images makes the messages feel important, with the brass chains and upholstered dresser mirror frames on burlap make the work feel fresh. The more I look at Stephanie’s work, the more I feel the perfect synthesis of the artist’s experience and her use of various approaches: from community engagement, mixed media, video to quilting. At times the work feels like symbolic shrines to heritage and culture. There are universal themes of love, family, dignity, language and also themes that should be universal, such as the right to exist.

“My work fuses a relationship between fiber and photography to examine performative behavior and the cognitive effects of forced cultural assimilation. My research surveys the psychological impact of intergenerational trauma, the politicization of afro hair, and unravels the everyday coping devices and affirmations we establish to survive. In addition to fiber and photography I further explore these concepts by employing video, sculpture, and community-engaged projects in my practice. My passion for interdisciplinary approaches and material language is evident through my cross-disciplinary collaborations, and the implementation of symbolic materials and imagery that examines domestic spaces, and alternative realities that reference Black American culture and the American South.”

Stephanie J. Woods is a multimedia artist from Charlotte, NC, currently based in Albuquerque, NM, where she is an Assistant Professor of Interdisciplinary Art at the University of New Mexico. In 2021 Woods was announced the Gibbes Museum 1858 Prize winner of Contemporary Southern Art and attended a life-changing residency at Black Rock Senegal located in Dakar.

Woods is also the recipient of several other residencies and fellowships, including the Fine Arts Work Center fellowship, ACRE Residency, the McColl Center for Art + Innovation, Ox-Bow School of Art and Artists Residency, and Penland School of Craft. She has exhibited her work at numerous venues including the Dakar Biennale located in Senegal, and Smack Mellon located in Brooklyn NY. Her work is featured in the permanent collection at the Virginia Museum of Fine Art, located in Richmond, VA, and she has been featured in BOMB Magazine, Art Papers, Burnaway, and the Boston Art Review.

Follow Stephanie J. Woods on Instagram: @stephaniej.woods

©Stephanie J. Woods, the wait of it II, 2020, a site-specific public art installation at the Richmond community hospital located on Virginia Union University Campus in Richmond, VA. Nine years of detangled afro hair formed into a loosely woven vessel, hand-harvested red clay from Winston-Salem, North Carolina, and umbrella tree. Dimensions Variable.

Greg Banks : Talk about your early beginnings and how you came to art/photography and how that led to this beautiful cultural, social, and political work?

Stephanie J. Woods: Thank you! I came to the arts when I was a kid, it was an innate thing about me. I have always been creative and have explored ways of expressing myself creatively, through theater, culinary arts, and orchestra. Yet, it all began with sewing, and me wanting to pursue fashion design. My mother signed me up to learn how to sew with a seamstress when I was in elementary school, and since then, sewing has been my pen and paper, alongside my brother, who used to draw at the kitchen table.

Byron is my older brother, and I look up to him, and I wanted to be like him; so, what that entailed was me emulating him. My brother is a graphic designer (art runs in my family) and so, I would try to draw different characters like Donald Duck and Goofy, just like he did.

When it comes to photography, because of my interest in fashion design and wearable objects, photography became a natural thing that ended up happening as a way of documenting my work. I majored in sculpture in undergrad, and my interest in sculpture informs a lot of the work that I make as an interdisciplinary artist. Yet, it wasn’t until grad school where I begin to embrace composition, wearability, and functionality. Photography is an essential part of my practice, and I tend to make sculptural props that are activated through the body, and the lens.

In terms of social and political narratives, I am extremely proud my culture and heritage. I used to work in a hair salon, as a shampoo girl. Also, I would draw these elaborate hairstyles, and ask my hairstylist at the salon if she could duplicate them in real life. With all the innovation and creativity within my culture I began to develop a visual language in my practice centered around my experiences growing up in the southern region of America and focused on creating metaphors that carry with them cultural capital and iconography. I do this through the implementation of symbolic materials that examine performative behavior, domestic spaces, and alternative realities that reference Black culture.

©Stephanie J. Woods, the wait of it, 2020, a site-specific five-channel installation, featuring moving audio photographs. Nine years of detangled afro hair formed into a loosely woven vessel, hand-harvested red clay from Winston-Salem, North Carolina, audio poem by poet Laura Neal, and an original score by artist Johannes Barfield. Installation view at Oakwood Arts, Richmond, VA.

GB: Talk about your process of making the multidisciplinary work?

SJW: I create work in space with whatever medium is best at conveying my concept; I see my work as collaging in space. I like to pick and choose materials and media that I feel fit well together visually and conceptually. It happens naturally, where material and ideas fuel each other. I go back and forth with process and concept. Sometimes the material is first and other time the concept comes first. My first resolved multidisciplinary work was Weave Idolatry, which I started creating at the beginning of 2014.

©Stephanie J. Woods, Weave Idolatry, 2015, woven synthetic/human hair weave, black body paint, salvaged antique gold frames, window cornices, and wool, dimensions variable. Installation view at the Weatherspoon Art Museum, Greensboro, NC

Weave Idolatry consist of five woven masks that I created from synthetic and human hair weave. I was gifted a suitcase full of hair weave and immediately went to the phrase weaving weave. Over the course of months, I began to make a series of woven wearable piece and it naturally unfold it into a becoming a photography and video series.

©Stephanie J. Woods, Weave Idolatry, 2016, 32” X 22” detail. Woven synthetic/human hair weave, and black body paint.

The video series includes an original score that was created by my husband and artist Johannes Barfield. My relationship with my husband has allowed me to embrace working across media. Johannes taught me how to edit videos and is a consistent collaborator with my work. Additionally Weave Idolatry led to many series of works centered around portraiture and repetition. It led to the creation of one of my favorite series A Radiant Revolution which is a mixture of many different materials, and language.

GB: Why and how do you use words in your work?

SJW: I began using text in my art in 2018 with my series A Radiant Revolution. A Radiant Revolution was inspired by these T-shirts that I found at a department store. I thought the shirts in the store were interesting, to think about the idea of wearing text on your body. Your body as an advertisement, or as a performance. The phrases I found on the shirt are my black is beautiful, strong black girl, and black girl magic. Depending on the spaces where these shirts are worn, they will have a different effect on the people occupying those spaces.

©Stephanie J. Woods, A Radiant Revolution III, II, and I, 2018, 9ft X 5.5ft each. Burlap dyed with sweet tea, woven brass chains, t-shirt, textile foil, polished furniture vinyl, red tablecloth, gold rope, dresser mirror frame, and upholstered taffeta print. Installation view at the Harvey B. Gantt Center for African American Arts + Culture, Charlotte, NC.

The use of text in my work originated from these found shirts but has grown to center around my interest in coping devices and protection politics. When you see me using text in my work that is reversed or flip upside down, I am insinuating that something is off.

I also use text in my FALSE ILLUSION series and in that work, it was more like diary entries or conversations about specific photographs as a way of recapturing what those images mean from memory. I also collaborate a lot with a poet Laura Neal whom I have worked with now since 2018 on audio poems that will accompany my moving audio photography works. The poems are written specifically for our collaboration. I’m not a writer, I do not write, so it’s also me trying to understand my position with language.

©Stephanie J. Woods, FALSE ILLUSION, 2020, Solo-Exhibition at Tiger Strikes Asteroid in Brooklyn, NY. “The exhibition features a series of large-scale textile paintings incorporating mixed media. Polished furniture vinyl laminates the textiles, turning them sculptural. Woods is critically engaged with black performativity, creating with careful and dangerous skill what may be discovered as the ‘Black Venn Diagram.’ The incomprehensible and overlapping relationship between truth and contradiction, between inheritance and advancement, and the impossible labor of black narrative and transparency.” – Laura Neal

GB: What is Protection Politics, and how does it play a role in your work?

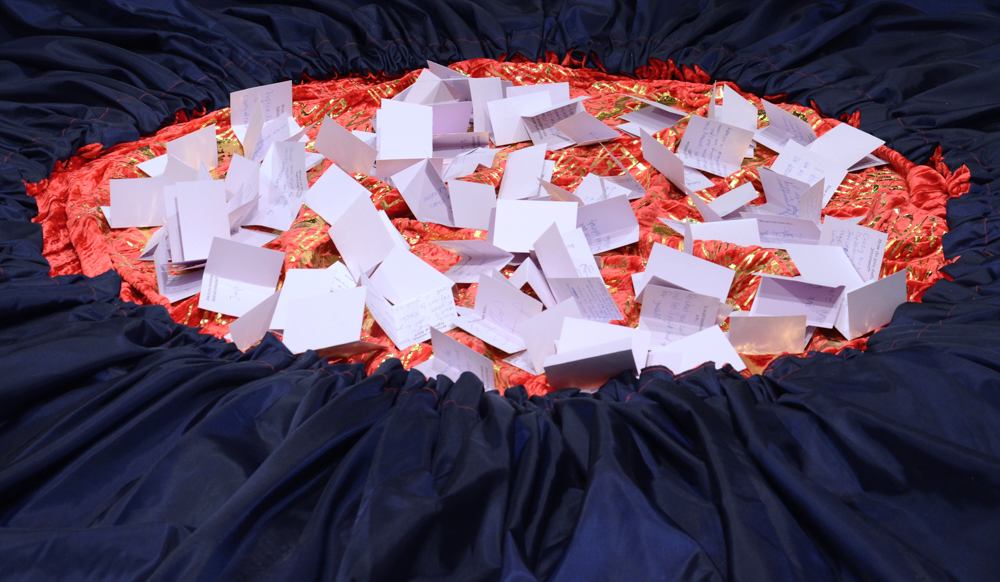

SWJ: Protection Politics is a phrase I created as a result of a community engaged project that I began in 2018 titled Relax Relate Release, which is a meditative space where we can express ourselves, laugh and play. I created RRR in response to my on-going battle to anxiety. The project is centers around the use of this eight-foot satin hair bonnet that I constructed to resemble meditation rooms. Additionally accompanying this project are six questions that I ask participants. I’m still currently doing RRR in different iterations, but after reading over 300 written reflections a lot of the responses felt like a survival guide, and so that’s where the phrase Protection Politics comes from.

©Stephanie J. Woods, Relax. Relate. Release. 2018-Present, velvet, textile foil, bean bag filler, lavender notes, and synthetic velour. Center circle 8ft Surrounding cushions 3ft X 3ft.

RRR has informed my video work “When the Hunted become the Hunters” and I also see this project growing into a book, and a summer camp; but I am still trying to make sense of it. Yet essentially Protection Politics is about self-preservation, and self-governing. What are ways that we maintain our dignity when faced with tribulations? Is it through affirmations and perseverance? And are these coping devices that we have established a form of defense developed for our survival?

©Stephanie J. Woods, When the Hunted Become the Hunters, 2020, moving audio photograph, seven minutes, thirty-nine seconds. Installation view at Smack Mellon, Brooklyn, NY.

©Stephanie J. Woods, When the Hunted Become the Hunters, is a defensive performance that features fourth of July audio captured on the porch of the artist’s childhood home in Charlotte, NC. In the performance, the artist is wearing hunting clothes and shielded by a satin bonnet that features an American flag that was dyed lavender and embellished with the text “The Right to Life.”

GB: How does community play a role in your work and with their engagement what do you hope to achieve?

SJW: If I did not have an audience to engage with my work, I would not be fulfilled as an artist. I remember when I used to copy my brothers’ drawings, I would put all my drawings into a book, and I take them to school to show my teachers and my friends. Sharing my work with others was the best part about making the drawings. I don’t make art for myself; I make art because I love sharing my work with others and having a back-and-forth exchange. Exchange not only fuels me as an artist, but I also enjoy creating spaces that are welcoming to my family and make us feel empowered and seen. My goal with the engagement is to hopefully cultivate a space of creativity, yet engagement is the newest part of my practice. I am an introvert, and I am usually the quiet one in group settings, so that’s something I’m still uncovering.

GB: How do you change or broaden other’s ideas about the experience of African Americans in America through art? Or is that even a goal?

SJW: My goal is not to change or broaden others’ ideas, I feel that is an unhealthy weight to carry rooted in white supremacy. Instead, I create work that I hope resonates with people that also, have had similar experiences. The idea that my existence as a Black woman is a political existence is absurd. Someone that is not an artist of color making work does not have to carry the weight of their work broadening or changing our ideas of whiteness, their work shares their experience as a human existing in the world, and that is what I do.

Greg Banks is a photo-based artist and lecturer at Appalachian State University. He received his MFA in photography from East Carolina University in May 2017. He received a B.A. in photography and a B.A. in fine art from Virginia Intermont College in 1998. Greg combines everything from IPhone images to historic 19th century processes, gelatin silver printing, painting and digital printing. His current creative practice investigates family, folklore, memories, magic, history and religion in Appalachia.

Follow Greg Banks on Instagram: @gregbanksphoto

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

Ricardo Miguel Hernández: When the memory turns to dust and Beyond PainNovember 28th, 2025

-

Pamela Landau Connolly: Columbus DriveNovember 26th, 2025

-

KELIY ANDERSON-STALEY: Wilderness No longer at the Edge of ThingsNovember 19th, 2025

-

Jackie Mulder: Thought TrailsNovember 18th, 2025