The 2022 Lenscratch Student Prize: 25 to Watch

Every year we seek to celebrate the next generation of photographic artists through our Student Prize Awards program. 2022 was a stellar year for photography, not only with a record number of excellent submissions, but the work itself reflected deep thinking and profound subject matter that it made it very difficult for the jurors to narrow down the selections. Before we begin the celebration of our 7 winners on Monday, we wanted to shine a light on 25 photographers that you should have (and keep) on your radar, artists who may be at the beginning of their photography journey but are already working at an elevated level, creating work that is deeply meaningful, especially in a time when change is critical. Congratulations to all! – Aline Smithson

We’d also like to thank our jurors:

Aline Smithson, Founder / Editor-in-Chief of Lenscratch, Educator and Artist

Daniel George, Submissions Editor of Lenscratch, Educator and Artist

Linda Alterwitz, Art + Science Editor of Lenscratch, Artist

Kellye Eisworth, Managing Editor of Lenscratch, Educator and Artist

Alexa Dilworth, Publishing Director, Senior Editor, and Awards Director at the Center for Documentary Studies (CDS) at Duke University

Kris Graves, Director of Kris Graves Projects, Photographer and Publisher based in New York and London

Hamidah Glasgow, Director of the Center for Fine Art Photography

Elizabeth Cheng Krist, Former Senior Photo Editor with National Geographic magazine and founding member of the Visual Thinking Collective

Allie Tsubota, Artist, Winner of the 2021 Lenscratch Student Prize

Raymond Thompson, Jr., Artist and Educator, Winner of the 2020 Lenscratch Student Prize

Guanyu Xu, Artist and Educator, Winner of the 2019 Lenscratch Student Prize

Shawn Bush, Artist, Publisher and Educator, Winner of the 2017 Lenscratch Student Prize

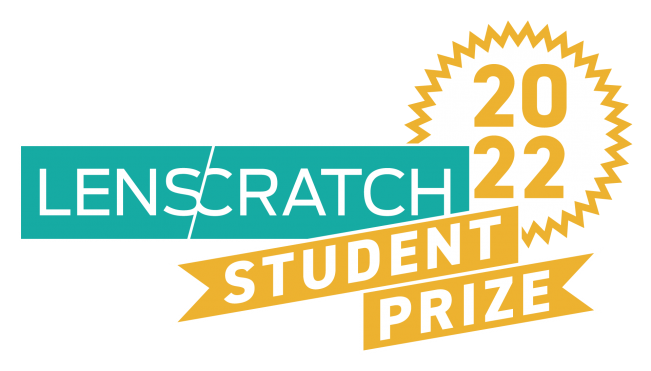

© Mackenzie Calle

International Center of Photography

“When the inkblots came up, we looked at them and, sure enough, we’d always see some feminine anatomy in there to make sure that we gave the proper sexual response.” Jim Lovell, an astronaut in the Gemini and Apollo programs, recounts one of two mandatory heterosexuality tests that early NASA astronauts were required to take.

To date, 600 people have been astronauts. None have flown into space as an openly LGBTQ+ person.

The Gay Space Agency confronts the American Space program’s historical exclusion of openly queer astronauts and asks what American heroism looks like and who might be a part of future exploration. Reckoning with this history, the project uses archival images, current images of the space program, and surreal boundary-breaking photos to reimagine a history which celebrates queerness and highlights LGBTQ+ role models.

In a moral panic beginning in 1950, the United States began a campaign known as the Lavender Scare to fire all “homosexuals and other sex perverts in government.” As a government agency, NASA was required to adhere to the executive order, which was officially signed in 1953, and prevented any queer person from being a federal employee. It was not repealed for over two decades.

In 1983, Sally Ride became not only the first American woman in space, but possibly the first ever out astronaut. However, this would not be known until 2012 when her obituary read, “Dr. Ride is survived by her partner of 27 years, Tam O’Shaughnessy.”

Today, NASA is joined by privately owned, billionaire-backed organizations in their exploration of the final frontier. As we revisit the possibilities of human expansion and future colonization, The Gay Space Agency asks what it mean to have the “right stuff?”

© Semaj Campbell

Lesley University

After encountering Latoya Ruby Frazier’s work, The Notion of Family, I began to the explore the options of manipulating the camera as a tool to consciously examine the world from an inward perspective that focuses on spaces and people close to me and how those images speak to my developing as a man, a black man, an artist, a black artist, a teacher, a black teacher, a human. From my curiosity of examining my own family dynamics, project Five Sixty Four began to take form and eventually took its first breath.

The Five Sixty Four concept origins are rooted in my childhood home located at 564 Wyona Street in Brooklyn, New York (East New York). This is the address where my great-grandmother purchased her first home after the murder of her husband and where she raised her six children and eventually remarried. In a way, that house and neighborhood is like a homestead to our family, as almost everyone in my family has resided there at some point in their life. Growing up, I heard family stories that always had a different twist depending on who the narrator was. Some of these stories still have lingering effects, as the past hinders present relationships between family members. Subsequently, these unresolved traumas can leave families and communities of low socioeconomic status filled with suppressed pain and masked scars. Such communities with households in the likeness of Five Sixty Four are largely comprised of black and hispanic families which are conditioned to bury our emotions and memories, not realizing the collateral damage it causes to future generations’ mental health. The disparaging effect is that the younger generations continue to go on not recognizing or knowing how to properly and effectively deal with their emotions in relation to trauma.

While using my family as a microcosm for the larger scope of many black families, the work presented examines how underlying traumas can play a part in the dark cycle of generational curses, or as science would classify it, generational mental illnesses and/or disorders. My work consists of two core components, one being an interview, where I have the opportunity to sit one-on-one with my family members and hear their stories with no interruptions from others. The conversations afford me the chance to connect with them on a deeper level while simultaneously learning more about myself. The second component is the photographing process, where I am tasked with capturing the essence of each family member within an intimate space prevalent to my family’s history, while narrating a raw truth through a beautiful pain of perseverance.

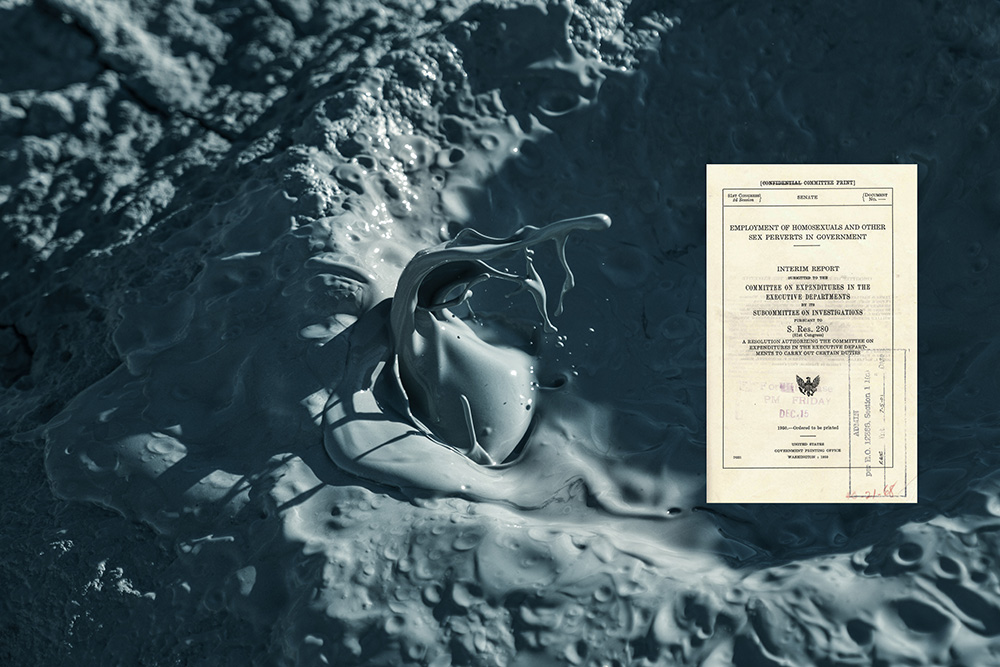

© Emmaline Carter

University of Cincinnati

In I Thought I Saw It in the Earth and in the Open Sky, I utilizes digital photography, video, and sound to examine the nuances of existing, remembering and healing after sexual and domestic trauma. Through these mediums, I explore how denying the viewer full access to myself and my body can be implemented as a tool to restore a sense of agency that was stripped away with repeated abuse. Additionally, I investigate the afterness of trauma as a site of liminality, and how I, along with other survivors who exist in this state of in-betweenness, may still find it possible to transition away from the unbearable and incomprehensible pain of remembering and into a place of healing. This place of healing does not dismiss the gravity of these traumas, nor does it pretend that these trauma’s will ever truly go away; instead, it seeks to understand how our experiences as victims can lead us to new ways of knowing, and thus new ways of hoping, dreaming, and living after sexual trauma.

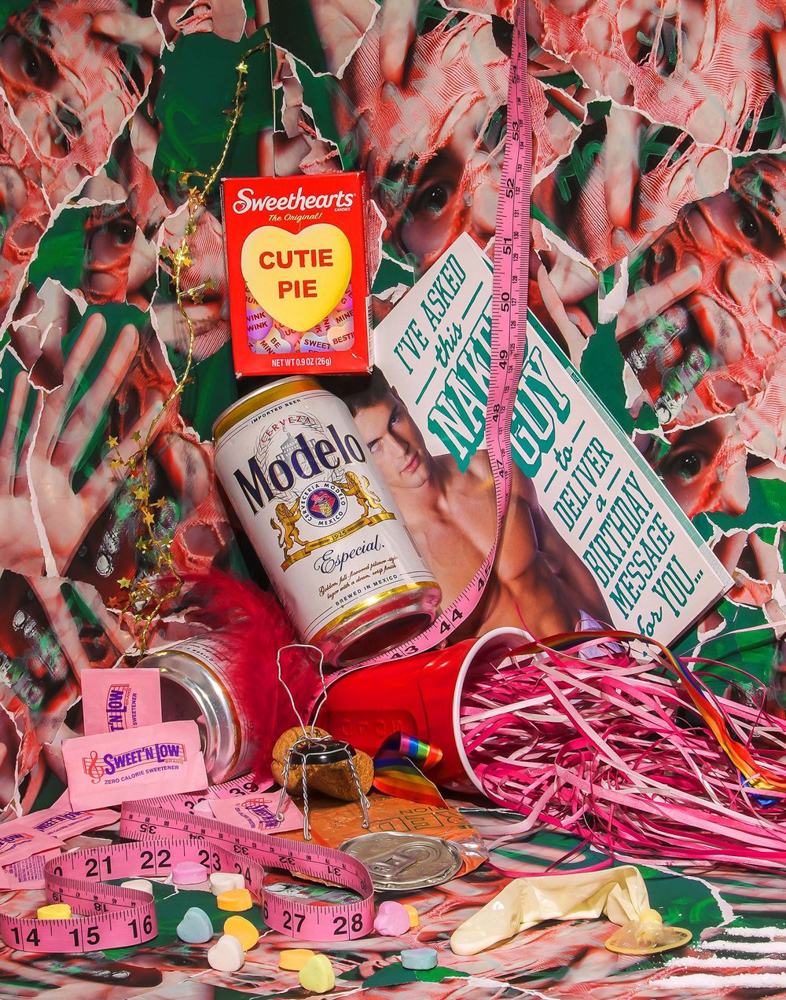

© Vicente Cayuela

Brandeis University

Juvenilia is a series of still lifes inspired by developmental trauma and romanticized notions of coming of age. Working at the intersections of collage, sculpture, and installation, I explore how photographs can be constructed to serve as a pathway to the regeneration of identity. Each photograph is a combination of graphic overload and visual bait, revealing narrative compositions that lie between the comic and the melancholic, the public and the autobiographical, youth and something vaguely defined as “maturity.”

By echoing the aesthetics of advertising and crowd-sourcing discarded artifacts from childhood, I seek to create modern allegories of youth that are both generational identifiers and shrines of personal catharsis. By representing adolescence as synonymous with survival, these photographs embody the mechanisms I developed as a queer person to fit into mainstream society, and later discarded in search of inner freedom and individuality.

Beyond camp and sentimentality, Juvenilia portrays the fleeting but pivotal moments of early character formation that, however quickly they may pass, leave lasting marks on our developing psyche.

© Noemi Comi

Brera Academy, Milan

Homo Saurus is an ironic/critical project that, based on the bizarre conspiracy theories about reptiles, stages an altered and dystopian world. The story is reconstructed through fictional documents that testify to the coming of the humanoid reptiles on our planet and within their home planet Nibiru.

Conspiracy theories about reptilians in recent years are receiving a considerable response, probably due to the economic crisis and the rise of populism. The conspirators present a distorted view of the history of humanity and the cosmos. Their intent is probably to justify their lack of power or inability to achieve work.

My project uses mythological elements to create ambiguous atmospheres, which are sometimes at the limit between reality and fiction; supporting but at the same time debunking conspiracy theories. A sort of encyclopedic gaze that, starting from a vision of the scientific world, rewrites reality and lays bare an attitude typical of hedonistic society: the construction of myths and fictions.

© Alex Delapena

University of California, Riverside

The sugar industry has brought multiple ethnic groups to the islands of Hawaii over a century ago. This convergence of laborers has helped shape contemporary Hawai’i known today for its diversity and merging of different cultural backgrounds that present local identity within modern Hawai’i. Yet, the value of sugar came at a cost.

Under The Bango Moon is a body of work that focuses on the Bango Tags utilized in the sugar plantations of Hawaii in the late 19th century. Plantation leaders in Hawaii needed to keep track of the various ethnic groups and had difficulties learning proper annunciations of laborers’ names. The solution was to utilize the Bango System. Bango is a Japanese term for “series of numbers,” and Bango Tags were a form of identification card. Each ethnic group is assigned a shape (circles, octagons, squares, rectangles, etc.) and a series of numbers. These identification tags were present before having Social Security numbers as a form of identification. If laborers do not have their Bango tag on payday, they will not get paid.

The photographs and freestanding images stages this history of early plantation life through a lens of theater and puppetry. Each still-life and the objects within my images are constructed physically for the camera. The representation of a full moon portrays a transformation of identity, like how Hollywood and urban legends depict the full moon as an object to heighten supernatural occurrences. The basic shapes within my photographs reference the different Bango shapes and, for me, also act as a stand-in for entities of plantation laborers of the past. The Bango shapes in the images are cutouts that have been covered in graphite powder to emulate a metal sheen and patina when light wraps around these crafted objects. It was my attempt to make these shapes feel like they had life by giving them a patina because of the reduction of identity and individuality during this time in history. The silhouette cutout traces the roots of early photographic documentation. The limitations of photography during the 19th century could not render motion as something still and sharp but instead a blurred dark figure that is anonymous, which is a common visual rendering within the archives of photographic history.

© Alice Fall

Bard College

The camera perceives things before I can. An image arises from a fleeting encounter of past and present. It performs a deceptive dance with the intangible. I trace the same images over and over to remember their shape.

The sun sweeps across the dead garden and heats the inside air like a greenhouse. The temperature is sweltering; it laps at my skin like warm water. My shoulders begin to burn but I still choose to sit in the sunlight. I open a window. The room begins to feel familiar; I close my eyes and hum a little. The space between me and the world echoes. Winter air leaks in through cracks around the windows, and I begin to notice pockets of one state inside another: invisibility within visibility, nonacceptance within acceptance, repulsion within attraction, separation within connectedness. Constriction pulses through the space, and these states begin to leak. The core of them, the delicate beauty of them, begins to rot. The interior expands outward, meeting edges and merging. My palms open fully and a momentary formlessness emerges, breaking through the confines and rigidity of order. Renewed and forever renewing; shapeless but in search of new shape.

The sun sets early. Emptiness moves in and saturates the space slowly. The remaining heat lingers and burns out. A low hum radiates from the yellow bulb hanging from the ceiling. It’s the only light on in the house. I move quietly from this room to the next, following voices that become more familiar as I approach. The space around me remains alive and my response changes every moment.

When I look through the lens and see my family, all of our identities are filtered and reflected back to me in an endless feedback loop. I can’t look into my own eyes without using a mirror, without someone opposite me looking back. The layers are illusive; they overlap and compound in a transformation that embodies multiple realities before they become something else entirely.

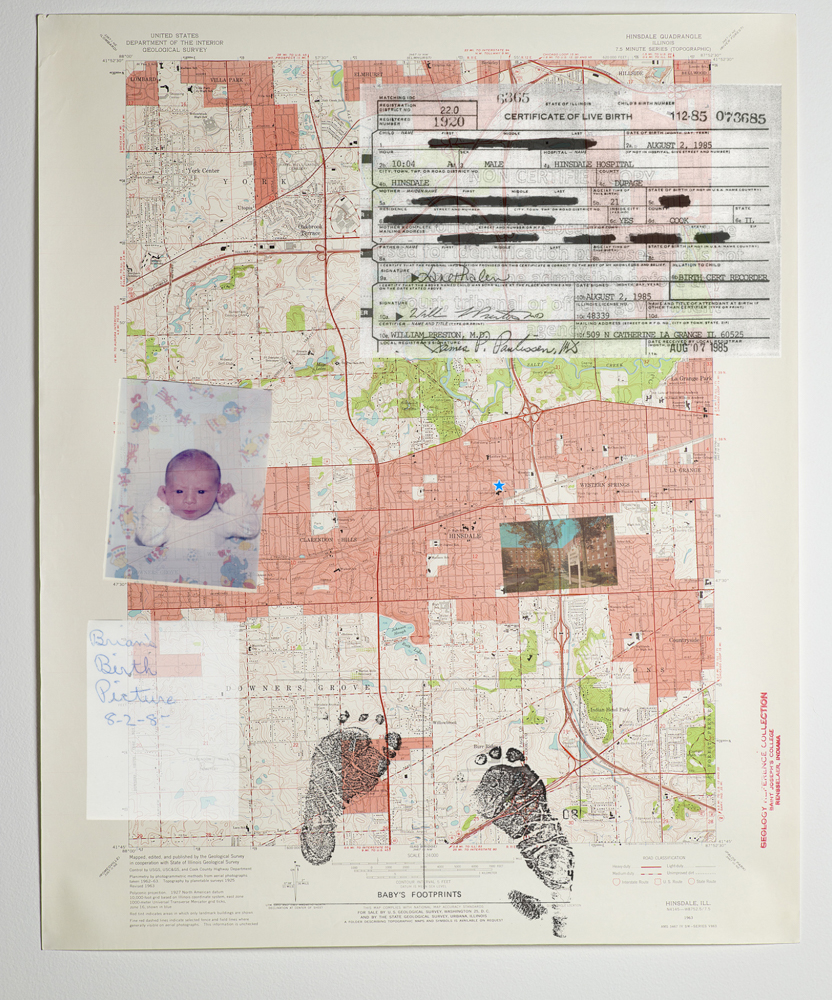

© Brian Garbrecht

Northeastern Illinois University

At the age of five, my mother told me I was adopted as we walked hand-in-hand in the warmth of a sunny summer day. A moment of confusion, comforted by the soft, loving voice of my mom, Paula. Since then, I wondered who my birth family was—not for wanting to replace the parents who adopted me but because of a curiosity that could only be satisfied by finding the people I share a biological connection with. For many years, information was pieced together from stories told at family get-togethers, as well as adoption documents found while snooping through my father’s office desk.

My search came up with few answers until 2010 when it was sparked by a change to Illinois’ adoption laws—which I was made aware of by a cousin who brought a newspaper clipping to a family gathering. In November of 2011 the new law went into effect, allowing adoptees to obtain their original birth certificate with identifying information. Along with this, access to online DNA services has helped me find biological family members that may have been impossible to find otherwise. To this day, I continue to find more information, revealing who I am and who my family is.

My family’s adoption story is told by bringing together original photographs, family archives, printmaking, video, and important documents. This is done through relating images to specific stories, as well as touching on themes of family, identity, memory, and loss. By connecting the pieces of my story, I implore viewers to think about their own definition of family, and how we connect to those around us.

© Megan Hansen

Central Washington University

Wild West Show speaks to a collective relationship to and understanding of the Western United States. Interpretation of the West is not formed by linear history, but by a complex, non-linear amalgamation of stories, revisions, myths, and popular culture.

Elements of Western Americana are combined through tableaux, collage, artist books, objects, and vernacular imagery, resulting in both a satire and a love letter to the region that I call home. Multiple layers of absurd mythology collapse onto one another, falling apart like the fragile notion of what the West is and what it stands for within an American identity.

The work depicts the American West through measures of ironic inauthenticity. I utilize a language of disingenuity and camp to ask the viewer to consider their own relationship to the West and its iconography, and the realities beneath the heroic Cowboy.

© Raisan Hameed

The Academy of Fine Arts, Leipzig

The mother – the first home and the last exile.

What might old family images look like in the future?

Why are some stories left behind while others are carried on?

With this series of photos from the family pictures I want to create a new form and perspective to tell a story.

Perhaps I am contributing to a broader understanding of the past, present and future.

My mother gave birth to me in 1991 while fleeing. The city of Mosul experienced air raids, so my family had to leave their home. I was born in the war and fled from the war. My generation was oppressed and deceived.

Through the family pictures many things become visible to me again, these cracks contain my memories.

Through this process of debate, the images lose their function and change the narratives. This creates an abstraction.

I always see it as a cycle.

Destruction is only one point in the cycle, it has to do with temporality and transience, which are hidden in it.

Nothing remains but memories, heavy with sadness and pain, and full of moments of surprise and joy. For man, perhaps, nothing remains but images.

The walls hide various memories from an open as well as mysterious world.

The cracks are perhaps a departure – to create something new and be different, or can also represent my wounds as well as injuries.

The symbolism of the place and the privacy of things are concentrated characters to show the contradiction between two different times and present and absent thoughts scattered on the glass.

© Jessica Hays

Columbia College Chicago

Wildfires are raging across the western United States, burning up increasingly large swaths of land every year. While fire is a natural part of many ecosystems, the increasing presence of larger, faster, and hotter fires is a reminder of the rapidly changing environment.

I began to seriously pursue this project after a wildfire in my hometown burned through a dispersed neighborhood and farming community in just a few days. I saw my community go through a collective trauma, each of us responding in whatever way we could. Just as the fires were reaching containment in my town, several other places important to me and near friends went up in flames. During that fire season, it seemed like the entire northwest, and almost everyone I knew, was experiencing climate driven megafires—and the devastation they cause—at the same time. News coverage of wildfires is fairly scant outside the communities that are actively burning. There was a missing piece in most of it as well, of the personal stories and community-based grappling with loss, grief, and trauma in the wake of climate disasters.

This work explores solastalgia, which describes emotional and existential distress caused by negative environmental change, generally experienced by people with lived experience closely related to the land. Lands integral to our identity, our livelihoods, and our wellbeing are shifting and changing without notice or control. The experience of a wildfire is all consuming. It crowds out your vision. The pillar of smoke is unmistakable as anything else. Our communities are facing collective traumas as we wait for news about the spread and containment, constantly refreshing web pages and data bases. Although these are localized examples of wildland fire and the trauma that follows, collectively the scale of these events is unfathomable. The day to day struggles of normal life continues on as fires rage outside our windows, setting our lives in a scene of gray oppression.

Integrating photographs, moving images, and text, The Sun Sets Midafternoon examines the immediate aftermath of megafires on surrounding communities and what the experience of local fires are like, interweaving narratives of ecological devastation, collective trauma, and climate grief.

© Daniel Hojnacki

University of New Mexico, Albuquerque

In No Solid Body is Lighter Than Air, my toenail becomes a moon, the soot from an oil lamp flame forms the substrate for negatives, and specks of dust on paper become the cosmos in this exhibition of my recent photographic works. I employ a variety of approaches to the camera apparatus and darkroom printing techniques to slowly and poetically situate ourselves within the universe.

This exhibition is an on-going investigation into ways of recognizing and observing the passage of time between my own body and the celestial bodies above. Photographing the cosmic space in connection with my body, I perform acts of mindful observation. I speculate on the origin of dust that is around us and within us. By using an early printing technique of cliché verre, I apply smoke soot to glass that leaves residues of my volatile body and breath in ash upon the page. This series of works are attempts at creating acts of suspension, momentary pauses, of finding the breath and being present in the vastness of contemplating time. No Solid Body is Lighter Than Air is a collection of visual stillness, of being one with the universe, to quietly celebrate the mortality and interconnected-ness of the human body to the natural world.

© Zachary Kaufman

Indiana University, Bloomington

This photographic essay, Wabash, Far Away, explores communities in transition. It examines the function of patriotism, masculinity and nostalgia in the process of creating the American Identity. The Wabash River is the subject of Indiana’s state song and is a symbol of the romantic rural interpretation of the Midwest, from which the contemporary photographs draw contrast. The waterway touches a cross-section of society indicative to the region’s large swaths of farming and rust belt communities, where families can be traced back for generations. Attitudes toward race, gender and sexuality are slow to change in America’s rural interior, yet change is inevitable.

Wabash, Far Away juxtaposes images of an exclusionary and idealized version of American identity with a much more complex and diverse reality in the Heartland. The generational inheritance of land, tradition and moral values are significant threads throughout the work. Although references to the past are included, the essay focuses on the younger generation who will ultimately decide the cultural course taken into the future.

For nearly four years I traveled much of the river’s 500 mile path, documenting the people who live along its banks. I spoke with many people who have generational connections to the land. During walks through communities I introduced myself and the project to local residents. Many of these interactions spurred conversations, where I concentrated on listening to their personal stories. Often these interactions led to a collaborative moment of portrait making. Empathy gives us the awareness and sensitivity to understand the concerns of others, which is paramount if we are to cohabitate respectfully and peacefully. Yet, the power of empathy isn’t relegated to understanding a person’s pain, plight, and/or challenges. We can also share in each other’s pride, joy, and expressions of love.

© Alexander Komenda

Aalto University, Helsinki

I was once told, knowing somebody for ten years or ten minutes can have equal meaning, and that those relationships are equally important. I say hello, bonjour, privet, salam-malekoum. I look people in the eye. I listen, I respond. I sit down, we break bread. We drink tea. I ask questions. I show love. I show respect. We smile. We laugh. We argue. I’m not a missionary. I don’t act like I know best or represent a society that does. This always comes first, before any photograph is made, taken, constructed, captured or created.

Following seven trips to Kyrgyzstan between 2016 and 2022, alongside both extensive field research, discussions and readings, this visual amalgamation attempts to refrain from any documentative purity. This is over half a decade’s worth of bearing witness to people putting on shoes like watching a glacier move. As much an observation as it is a meditation. As much my father’s workplace, who works as a human rights advisor, as it became my workplace, as a photographer. Following the collapse of the Soviet Union, Kyrgyz areas of the Fergana Valley have been subject to interethnic clashes, mostly between Kyrgyz, Tajiks and Uzbeks. In 2010, there were violent clashes between Uzbeks and Kyrgyz in Osh and Jalalabad. In 2021, allocation of water via old canal systems fueled a new conflict in the Batken region between Tajiks and Kyrgyz. Minorities such as Uzbeks and Tajiks are often subject to discrimination. These events, tainted by a post-imperialist former Soviet landscape, are reshaping these regions in relation to everyday life, such as a rise in nationalist sentiment via government action.

The camera is an opportunity to reach out via kinship and reciprocity. Where is the line between division and unity? What does everyday life look like with this backdrop? How can anti-sensationalist visual narratives address such contentions that encompass its many nuances? These are all questions that inform the making of these images. The everyday, collective memory and history can all have a place both within and between images.

© Drew Leventhal

Rhode Island School of Design

My project, Mason & Dixon, traces the footsteps of the original surveyors of the Mason-Dixon Line and their search for purpose in the borderlands between Pennsylvania and Maryland. For the past 250 years, the Line has inscribed a violent and painful scar on the land, filled with memories and (re)written histories. Holding the legacies of slavery and colonial expansion deep in its soil, the region is now a visceral example of the ongoing divisions and conflicts around the past, the present, and the future of the United States. The friction is in the air, it is in the monuments, and the clearcuts; all part of the invisible cartographies that frame our identities. I often ask myself how the land can support this unbearable weight.

I photograph along the Mason-Dixon Line because I am looking for connections between the divides: connections to the people I meet, to the land I grew up on, and to the history I am a part of. The irony is that the relationships that bind us are also the stories that divide us; that make a miasma that is perilous to traverse. But when I cross the dividing Line nothing changes, even though the signs say it is there. When I cross the Line it becomes mythology and I am left searching for a constellation on the ground I cannot find.

The Mason-Dixon Line is a line we all draw as we try to manifest an American identity. Utilizing large format black and white photography, the images in this project are my ethnographic observations of a nation unsure of itself. They are my accounts of where we have been, where we are, and where we are going.

© Lucie March

Massachusetts College of Art and Design

I’ve been imagining a wordless return. It is a deep reddish-orange, like when you close your eyes and light comes through your eyelids. It is the dark warmth of the womb. It is my grandfather, who made his own wordless return to a place with no memory. It is my father’s frailty. It is a photograph and a fossil and a star. It is the dissolving of myself into previous millions of versions of my body.

I go to the natural history museum where everything is still, inanimate — all the rocks and bones in their display cases. The plaques bear numbers such as 245 million years, an unfathomable reach of deep-time. These skeletons once roamed the earth in the shape of ancient armadillo or dinosaur. Now they are forms imprinted in rock, marks made by bodies already dead. Through excavation and preservation, they live a kind of second life, but it seems to me they die continuous deaths behind the museum glass. Frozen in time, they are like photographs masquerading as proof of life when in reality they are evidence of death. In her book Nonhuman Photography, Joanna Zylinska positions the photograph as a reminder of the sun, an awareness of our own extinction. As I drift farther and farther back through time in the quiet carpeted rooms of the museum, I find tucked away in a corner of the Vertebrate Paleontology hall a series of tiny footprints fossilized in a slab of rock. Dinosaur Footprints, the label reads. Fossil footprints are a record of an animal’s activity when it was alive.

I’ve begun to take note of traces in the world around me, imprints of presence, evidence of existence. I saw on the floor of a train car hundreds of footprints, brief fossils made from people’s salt-encrusted winter boots. I saw tire prints on the street where a car had turned around, forming a circle of lines like a massive ammonite in the middle of Somerville Ave. I saw a handprint of paint on a window near my studio, a record of a momentary impulse whose duration is stretched into a long touch.

These traces are mysterious, ambiguous proof that I am here, that you are here, and that we have been here together always. We go to the natural history museum to see ourselves as simultaneously Now and Before and After. The farther back I go the more connected I feel. It reminds me of genealogical charts — if you go back even just a few generations, you suddenly have thousands of cousins. The number grows exponentially with each drift backwards in time, until we are all related, made of the same stuff — earth and water and rock and dust.

It reminds me of this passage in Virginia Woolf’s The Years: Does everything then come over again a little differently? she thought. If so, is there a pattern; a theme recurring, like music; half-remembered, half-foreseen?…a gigantic pattern, momentarily perceptible? The thought gave her extreme pleasure, that there was a pattern. But who makes it? who thinks it?

For some of us, if we are lucky, right before we die we will see these disparate half-remembered, half-foreseen glimpses of our lives unfold in dusty red flashes underneath our eyelids — the final blinking sequence of our existence.

© Miraj Patel

Yale University

Having studied science, I have a strong desire to experiment and push the boundaries of what I can get photography to represent. I look to the past to see what has come before me, so I can disengage from conventions and add to the conversation, rather than echo it. In this body of work I began to deal with childhood trauma from trying to assimilate in a foreign landscape with no guidance. As a child I had to navigate two cultures and felt constantly estranged from my parents and the world around me, eventually choosing one over the other. In recent years I’ve began unpacking my decision as a child to reject my Indian culture in hopes of fitting in with my peers and how it has shaped my desires, interests, memories, and inner-voice. During this process I’ve used the camera as a means to dig deeper and recreate interpretations of my past experiences and have created new ones as I explore my identity as an Indian-American.

© Alana Perino

Rhode Island School of Design

Pictures of Birds is an ongoing series examining selfhood, family, and home. Longboat Key, a Floridian island of condos and snowbirds, became the strange backdrop of my parents’ fading health and their children’s mourning process. During my visits, I immerse myself in the fears and aspirations of people preoccupied with death. I am drawn to how posture and gesture reveal the psychological. I call attention to the arrangement of a retirement community landscaped to affirm health and wealth and attempt to show the ways that this façade is compromised by the ever-present nature of illness and mortality. I search for the entanglement of the mundane and strange in domesticity, trying to reveal the hauntings of ancestry. This project is a deeply personal investigation of the traumas and privileges that shaped my family’s values and my concept of self and home.

© Amir Saadiq

University of California, San Diego

Like many, my introduction to the Nation of Islam (N.O.I.) was through the autobiography of Malcolm X. This book changed my life and sent me on a different life trajectory. It led me to Howard University, where I was exposed to Black people empowered and freely expressing themselves. Being raised in the Deep South, I have seen the weight of systemic racism bearing down on people of color. While living in the Bay, I watched police kill Shaleem Tindle, Mario Williams, and countless others. Their death impacted me deeply. After the 2016 election, I watch microaggressions bloom into flowers of hate. I picked up a camera for the first time and committed myself to social justice and inclusivity in the arts. I photographed Wanda Johnson and Gwen Brooks- mothers who lost their sons to state violence. I became reacquainted with the N.O.I. They were present at many of the events in the community. It Takes a Nation initially explored the men and women who joined the N.O.I. The N.O.I. helps many Black people survive racism, drug, and mass incarceration by providing a newfound sense of purpose. I see myself and many other disenfranchised people of color in them.

As I am completing my second year of grad school, working towards my M.F.A. in visual arts at UCSD, I understand that my practice is about the impossibility of Blackness. My practice addresses systemic issues that impact people of color. It Takes a Nation is an intervention.

© Anastasia Shubina

Docdocdoc School of Modern Photography, Russia

Amanita plays a symbolic role in the culture of many countries, being both attractive and repulsive. Many people believe that it is deadly poisonous. Indeed, that has been used for centuries to kill insects, from which it got its name. Others, on the contrary, are sure that it is a delicacy, can be used as a medicine, cosmetic and massage agent, and an antidepressant.

In ancient times, fly agaric was used in shamanistic rituals to meet spirits and was considered a way to magical reality. Perhaps it was fly agaric practices that served as the basis for a number of plots and characters of ancient myths and fairy tales. There is a renaissance in the use of fly agaric in the world: its microdoses are used to treat depression, as a tonic; the visual of fly agaric is used in art and design; neo-pagans use it in their rituals, but it still remains a symbol of the most poisonous and dangerous mushroom.

The duality in relation to the fly agaric, ranging from admiration to horror, reflects the ambiguity of a person’s perception of traditional culture and magic, which combines mistrust, fascination, irony and fear.

© Seok-Woo Song

Korea National University of Arts, Seoul

Wandering, wondering is a story of all of us, becoming adults, getting more socialized, and living in a systematic social structure. No one has forced or oppressed our lives. Without looking back, we live in a life that fits already into the familiar flow following only dreams and ideals we’re aiming for, the naturalness of time that goes by constantly. Through this work, I have a chance to explore for my 20s already passed by and past time which entered between the gap of familiarity.

These produced images are stories intended for the young who cannot adapt to the social structure which is changing quickly, above all men in 20s. The eyes coming from between unfamiliar spaces and strangers are begun by wandering around places and environments where you can get someone else’s feeling such as strangers and universally abandoned spaces. Based on feelings caused by loneliness, emptiness, the gazes that didn’t approach in a good what I experienced in society, I express floating or unadaptable objects in the world by images.

This work leads to subtle psychological change and expansion of consciousness that occur between individual consciousness, different dimensions of time and space, and meetings of objects. And It also is produced by freely combining images across the boundary line of consciousness and unconsciousness based on social factors and narratives with characters. I was concerned about relationships that people build up with others and mainly intended to explore the way people interact and the social principles involved in it, using gesture language.

I hope that not only 20s, but everyone who encounters this work will be able to sympathize by watching the gesture language of the process head for society in this work, reminiscing about their past or expecting their future.

© Ashley Ann Vaughn

San José State University

The Mission Project is a conceptual tracking of person in connection to place. An examination of familial history and personhood in connection to the Colonial Apparatus in Function. Colonial Apparatus meaning systemic and social normality resulting from European contact and eventual “settlement” of, what is now known as the Southwestern United States. That although we are living in “post-colonial” times, the apparatus or systems developed on this land for control of the indigenous and other subjugated populations is still the present. That these systems are woven into the social and legislative fabric of the construction of United States.

This piece, also references the image-based propaganda that the camera is historically implicated in. These systems (although less overtly) still perpetuate institutional racism based in control and detriment. This research is the backbone for the development of a photographic based body of work, which intends to understand the complexity of my own matrilineal decent. I seek to analyze the normalization of Anglo centricity to the loss of understanding my own familial ties to indigeneity. A process of Americanization hand in hand with cultural erasure. I have observed this erosion of history which has occurred generationally.

My grandmother was born in Raton, New Mexico in 1934. I am centering this body of work around understanding better our family’s movement from New Mexico to California in the early 1940’s. My maternal great grandmother was indigenous to Northern New Mexico, specifically Toas, and Raton (Diné; Spanish Colonized, Jicarilla Apache). The work focuses on our matrilineal decent, illuminating our unique journey in connection to the whole of complex American histories. I am openly and critically examining the steps of our journey to better understand my own history and personhood, emphasizing the Mission Systems Movement through the Southwest as personal and familial markers of time, cultural practices of white washing as a result of colonial occupation, and contemporary familial post-colonial understandings as a result of these regional waves enculturation. First as New Spain, then as Mexico, and now as the United States of America.

The installation is composed of familial archival scans, conceptually based familial photo restoration, 35mm conceptual imagery, medium format familial prints, photocopy & found vintage illustration collage, emulsion lift, & image transfer, papier mache shadow boxes, and conceptual approaches to video. All works created during my time here within the SJSU MFA photography program, to help articulate the complexity and contradiction of post-colonial personhood. My journey begins from a desire to reclaim what was lost.

© Ian Edward White

Rochester Institute of Technology

I Heard the North Wind Call Your Name is a photographic series of portraits and post-industrial landscapes made in Rochester, NY. In the fall of 2020, I began wandering, hoping through photography, that I could make connections with people and gain a better understanding of my new home. With no agenda in mind, I allowed myself to become comfortable with the unknown – to follow my intuition and curiosity wherever they took me. Chance encounters and conversations with strangers often turned into portraits. My work, and understanding of the city, are informed by these shared experiences with my subjects.

I am concerned with a sense and rhythm of a place and invested in making photographs that speak to my personal experience of Rochester. Exploring themes of longing, anxiety, and resiliency, my work is an interpretation, rather than a documentation. My project won’t tell you what to think about Rochester or its people, but hopefully, it can show you that being open and engaging produces meaningful records.

© Suzanne Theodora White

Maine Media Workshops

‘I look to the land, and it tells me stories. An artist needs stories.’

I have always been profoundly connected to the land and understand that it is the memory keeper of our planet. I have lived on a farm in Maine since the 1970’s and when having a survey done on the property, I was astonished to discover that the farm had once been in my family during the 1850’s. As I walk the property, I can feel the geologic and human energy of what has come before as I contemplate our future during this time of upheaval.

The Weight of Memory is an investigation and expression of grief and solastalgia as my farm becomes a casualty of a warming world. My constructed theaters are dramas exploring the consequences and metaphors of climate disruption. I examine and confront what remains in the hope of finding beauty in the remnants. As we live out each year, we become accustomed to a new normal. Generations growing up now won’t remember when the skies were filled with birds or when insects were abundant. We who have born witness, bear the weight of memory. What will happen when there is no one to remember? How will we restore our shared natural world? If we can embrace the knowledge of what used to be, and come to terms with what we know presently, we will understand what can be, and find the hope, love, and determination artistically to reclaim our natural world as we journey through the Anthropocene.

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

Shane Hallinan: The 2025 Salon Jane Award WinnerFebruary 12th, 2026

-

Greg Constantine: 7 Doors: An American GulagJanuary 17th, 2026

-

Yorgos Efthymiadis: The James and Audrey Foster Prize 2025 WinnerJanuary 2nd, 2026

-

Arnold Newman Prize: C. Rose Smith: Scenes of Self: Redressing PatriarchyNovember 24th, 2025

-

Celebrating 20 Years of Critical Mass: Cathy Cone (2023) and Takeisha Jefferson (2024)October 1st, 2025