Memory/Loss Series: George Slade: My Father’s Shirts

© George Slade: I recognize a version of my father in this resurrected print, which probably predates my arrival in his world. I’m not sure if I understand the moment or remember this particular aspect of him. A bit of self-consciousness, a hint of dash, a flushed face, and a descent into shadow. Undoubtedly I read too much into this to see a portent for his eldest child, a kind signal about the potential for decline. Nonetheless, there it is, what I make of it, today. The expression and the photograph, drawn of and from warmth, arouse longing and untethered loss as another end-of-year coalesces around us and the familiar man continues to recede. Did I miss something then, in the image in front of me, or am I losing something now as I cradle this flickering, ambiguous memory?

Welcome to the sixth feature of our Memory/Loss series, showcasing photographers who explore themes related to family, grief, aging, and caregiving. Many of the artists grapple with Alzheimer’s disease, in particular, using their cameras to tell intimately personal stories of their loved ones as their memories fade. The CDC estimates that in the United States alone, 5.8 million people will be affected with Alzheimer’s and other related dementias. That’s about 1 in 9 people, making it a tragically common experience for so many families. Moreover, because the disease is genetic and there is no known cure, many wonder if their genes hold the same fate. This collective of photographers from across the globe shed light on the reality of this terrible disease and the memories and loss associated with memory loss.

This series is organized by Hannah Latham in collaboration with Aline Smithson. Latham completed her thesis, Bring Me A Dream, at Rhode Island School of Design, which focuses on the tragic decline of her paternal grandparents. Inspired by her grandmother’s experience with Alzheimer’s, Memory/Loss features a series of photographers exploring similar themes.

Visit the Alzheimer’s Association’s resources to learn more about the causes, treatments, and how to help.

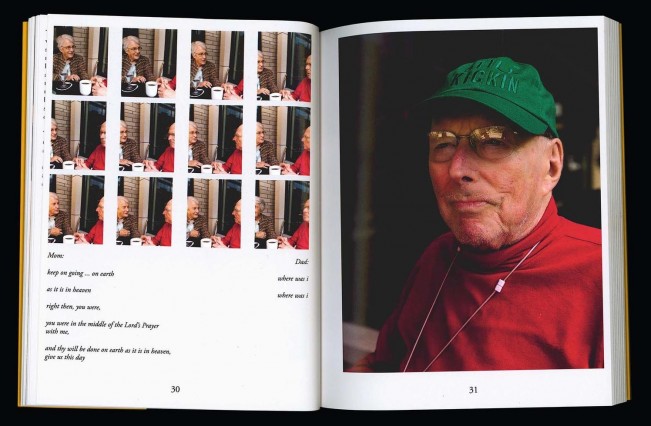

© George Slade: “Just getting rid of a stray eyebrow,” Mom says. Dad tolerates it like a seven-year-old getting his hair pushed back on his forehead, “so everyone can see your handsome face.” Her reality has always been so intertwined with his. Now, when his reality is, as far as we can see, a psychedelic wandering through terra incognita, she is at a loss. To put it mildly. He was, though, clearly tuned to her wavelength. From where I was sitting, if not from where she was. The challenge is being with him where he is, however inscrutable it seems to us outsiders. He reached out to her several times during lunch yesterday, placing his arm solicitously on her back and regarding her with what passes for delight. He didn’t eat as much of his pulled pork sandwich as she would’ve liked (“you’re getting so skinny, Richard”—followed shortly by “I’m sure your son will be willing to help finish it”—which is true, and the reason I only ordered toast and fruit). He shook his head after each bite she fed him though he did enjoy his coffee with, get this, cream and sugar.

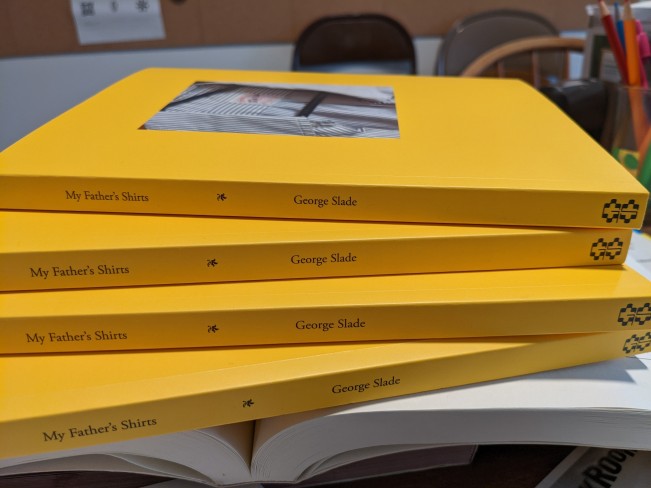

George Slade’s series My Father’s Shirts is striking to me in the way he uses social media to bring the experience of Alzheimer’s, whether experiencing it firsthand or witnessing it in a family member, to a larger stage. It humanizes what it’s like to live with the disease in a way that is accessible and relatable to others while bringing awareness. I also appreciate how he highlights the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on the elderly, especially those dealing with memory loss. Slade has created a book of this work under the same title and it can be purchased HERE.

“GGS” is George Slade. He was born in St. Paul, Minnesota, in the early 1960s, and currently lives in Minneapolis.

His father, George Richard Slade, the subject of these photographs, was born in 1931, was diagnosed with Alzheimer’s in 2018, and is known as Dick. His father, George Norman Slade, was known as Norman. Norman’s father, George Theron Slade, was known as George. Just like his great-grandson.

George Slade learned photography using his father’s Pentax single-lens reflex camera throughout high school in St. Paul. Later, out East, he studied photography with Alan Trachtenberg, Ben Lifson, Tod Papageorge, Garry Winogrand, Sally Stein, and Rosalind Krauss. Eventually acquired a Leica, which he still owns and has used to shoot film in the last twelve months.

© George Slade: Dad had a hard time distinguishing between his mother, who appears in the small print, and my mother, who occupies a large part of this picture space (and looks so much like my sister @visual_reshere that it’s uncanny). His finger waggled uncertainly at one, then the other, as though trying to discern between Mom one and Mom two. Tuesday is Mom’s birthday. She has always had an outsized presence in our lives. She is bearing an outsized burden as dad slides further and further away from us all. So few of us are able to grasp the peculiar circumstances of her generation’s women. High achieving talented women who nonetheless often opted into roles as the Mrs. to her husband. You know the syntax: Mr. and Mrs. G. Richard Slade. She no longer disappears within his aura, but she struggles with the daily loss of her lodestone.

Worked as an editorial assistant and researcher at Aperture, Magnum, Archive Pictures, and the New York Film Festival in the 1980s. Returned to Minnesota in 1990. Served as director of McKnight Foundation Artists Fellowships for Photographers program, as artistic director of the Minnesota Center for Photography, and in consulting curatorial roles at arts organizations around the United States.

Realized at some point in the early 2000s that digital photography and mobile phone cameras were helping him recover his interest in making pictures. His active Instagram feed “rephotographica” has well over 4,000 images; he posts #myfathersshirts images there, and in combination with other Alzheimer’s-related content, including links to various portfolios and publications featuring contemporary imagery on Alzheimer’s, on a Facebook page called “My Father’s Shirts.” His writings on photography, including book reviews, profiles, and catalogue essays, have appeared in numerous electronic and print venues over the past 35 years.

Follow George Slade on Instagram: @rephotographica

© George Slade: “Hello, dog.” Sugar is Mom’s dog. He’s become her closest companion as Dad careens toward his future. Sugar is the third quadruped and the second dog—after Corky, a skittish toy poodle—to join our family primarily for her benefit. (One cat, Butterscotch, was an ill-advised anomaly.) We knew a stream of black and yellow Labradors, hefty, service-oriented creatures tasked with upland gamebird hunting and the random downed duck retrieval. I was enamored of the genial, long-haired Dachshunds Dad’s father had; Chester was one that joined our family years after Grandpa Slade died, an echo of those silky, charismatic dogs who seem reincarnated in Sugar, a rescue of indeterminate breed. I sense my father’s innate gentleness here. Frailty aside, this is Dad at his core—curious, solicitous, unselfconsciously caring. His distance from fellow humans, occasionally noted through his life and inescapable now, effaced by a kindred, canine spirit.

My Father’s Shirts

His Alzheimer’s is helping me embrace our history.

This series of images and texts found form in social media. I write the texts with the same tool I use to capture the images. A confluence of thought and impulse compels me. Facebook and Instagram have their drawbacks, true. But I find a lot to like—immediacy, reach, and exchange are foremost. Dialogue between me and my father stimulates others, and real-time connection occurs. Alzheimer’s touches so many lives; people—mostly strangers—express their gratitude to me and openly narrate their own journeys. My observations intersect with and encourage other people’s words. I am creating a forum in which experiences can be shared; my progress through Alzheimer’s is no more or less ennobled than anyone else’s. I’m pleased to welcome exchange without insisting on my view as more qualified or capable. I don’t think of the texts in this project as captions. Neither form of image, lensed or lettered, has primacy. In my earliest posts I recognized the need to wrap the images in words. They coexist in a necessary, interwoven fashion.

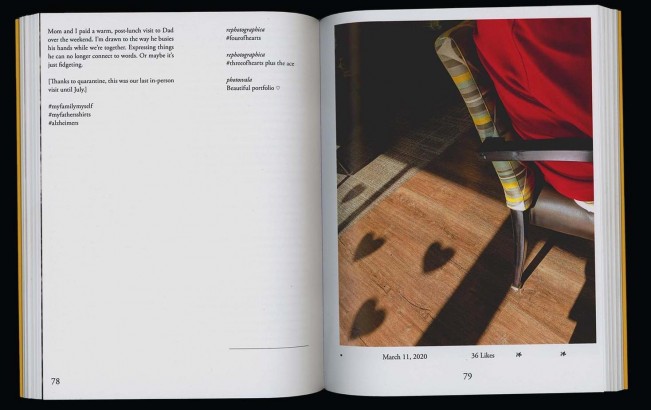

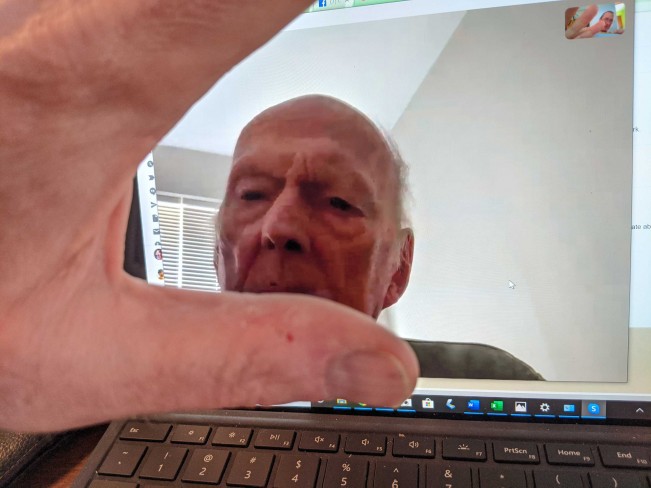

© George Slade: Reaching out and (almost) touching someone. Today, a second go at a Skype connection with Dad. He was more clued in to the moment; Tommaso helped interpret. Shared a few observations about life with the man in the screen (me). He smiled when I sent him a ❣️ on the screen. As we were wrapping up I held my hand out to the camera. On the other end Dad lifted his too. I was touched. No question.

Coronavirus restrictions had a chilling effect on this work. For seven months the irreducible quality of proximity was withheld; digital visits were thin substitutes. The emotional scale of our visits morphed into black-and-white reprints of “old” photographs. Physical access loosened up somewhat in late summer. I am now an “essential caregiver.” I can enter the memory care unit and sit next to Dad, hold his hand, talk some and (mostly) listen to his errant monologues. I offer companionship, and he reciprocates. Our visits are exquisite opportunities to share moments after decades of over-complicated, historical agendas. This window is only conditionally open; public health guidelines may slam it shut again. And, who knows how long Dad will live? He has been on a hospice protocol since before Covid; he is strong, even as his mind is beginning to forget how to keep the systems running. While publishing a book of this work is an attractive long-term goal, I feel it has ample justification to continue on the social platforms it currently utilizes. The opportunity to reply to comments in real time is truly profound. Right now, a book would create more distance than it would bridge. Support from the Bob & Diane Fund will allow My Father’s Shirts to develop into a more robust and sustainable web-based forum. The work exists as an oasis, a layover on the long journey that is Alzheimer’s. As long as my father is alive, the potential to create these visual and emotional snapshots remains. These are three-dimensional photographs—height, width, and spiritual depth—that value immediacy. In this time of enforced distance, why not encourage a space of connection?

© George Slade: When food—in this case, meds-laced vanilla pudding—hits his lips, Dad has a moment of clarity. His surroundings, including the presence of others, glide into focus. A glint of awareness registers in his face. I’m fairly certain he hasn’t interacted with many Somali women over the years; I also know that his heart has been receptive to most humans. This expression puzzles and intrigues me. Maybe it’s the earnest gaze of an infant decoding a new arrival in his world. As we were leaving, she stood by his side to keep him from tailing us out of the memory care unit. He turned to look at her, this seeking face returned, then he leaned down, leading with his lips as though intending to kiss her. These incredibly gracious staffers know how to deal with this not uncommon gesture—they just turn their face away. “You’re not going to bite my ear, are you?”

Tell me about your coming of age and what brought you to photography

My father had a great deal to do with my early interest in photography. He and my mother used to make grand journeys around the world, and when he returned he would process the rolls of Ektachrome he’d shot during the trip. A few days later, my siblings and I would gather in front of the glowing projector screen and listen to his quirky narration while the slides clicked and clacked through the carousel. I developed a love for the images and the sound of his voice. Of course, it was very rare to see him in the photographs, given that he was always the one carrying and using the camera.

Dad also kindly allowed me to use his Pentax SLR to expose film in a self-educating way. I would finish a roll, put it on the piano near the front door, and before I knew it the film returned as prints. Like magic! I didn’t learn how to use the darkroom until I was a junior in high school. And I neglected to do the assignments in my photo class that year, so I had to complete them during the summer.

© George Slade: After dinner Milan and I took Dad out for some fresh air. Since the sidewalk in front of the building was slicked over and light snow was falling, a considerate staff person opened the first-floor patio for us. Milan raced out and started flipping “snow burgers” at the grill, landing some on the ground in the process. Dad shuffled around, guided by some nameless agenda. He paused to poke at one of the antic chef’s wrecked burgers. See his tracks here. Like a baby turtle’s instinctive path toward the ocean, I thought. Snow flecked his sweater and neck as he drifted through the glow of this anomalous, off-season space. Folding in the image of his flickering dinner drink, I realize how much Dad now resembles a toddler, vulnerable and curious. As we walked him back to his room in the memory care unit I reconsidered these slipper prints. Turtle tracks are baby steps. In this case, an 89-year-old’s baby steps. He’s simultaneously moving forward and backward in time, losing a little capacity with every attenuated step.

What does your photographic practice look like, and what brought you to this subject matter?

My practice looks a lot like that of countless millions of other people who carry cameras attached to their phones. What distinguishes me, I suppose, is that somewhere along the line I discovered a joy in using photographs to communicate distinctly visual messages and connect with others. Again, the slideshows factor in, having instilled a pleasure in hearing my father link his voice with his images.

I believe some photographers were meant to make great prints, and I readily admit that I’m not among them. Instead, I love that photography enables the opportunity to share and receive feedback from a supportive community. I photographed extensively through college and was the photography editor of the yearbook in my sophomore year. I photographed theater and was always pleased to see my pictures hung in theater lobbies and reproduced in publications.

Through engagement with digital imaging I became a recovering photographer.

What have you learned throughout creating this body of work?

Making the photographs in My Father’s Shirts was a singular experience. Imagine taking the time to be with one of your parents, sitting knee to knee with them as you provide nourishment, companionship, and attention. Usually I visited for an hour and a half, and helped Dad eat his breakfast. Read to him. Listened to music. Three times a week. For many months.

I learned that dementia changes relationships. And that close attention to a loved one experiencing dementia (Alzheimer’s in my father’s case) can be revelatory. I became close to my father in a way I hadn’t ever been. It was pointless to try and get him to reconnect with the person he had been for the first 85 years of his life. There was, however, pleasure to be found in his moments of expressive, if qualified, lucidity. Being present was the key.

Sharing this work on Instagram has been critical. During Covid quarantine my world consisted mainly of my father and his memory care colleagues (I can’t say enough about his caregivers, how they helped me as well as him), the texts I wrote in Instagram’s cramped caption space, and those in the IG world who chimed back support, love, and encouragement. I found my community; there were over 116 individuals who offered written comments to me during the three years of this project.

Who are your biggest influences / what inspires you to create?

I suppose the obvious answer is that my father has had a huge influence on me. Doing this project has helped me understand the emotional nuances embodied in that influence. He was a banker who became an art college president. Talk about dramatic changes of direction!

More generally, I think photography is most appealing as a tool to record the everyday extraordinary. John Szarkowski once observed that the great French photographer Eugene Atget functioned as a pointer. His images called your attention to features of the world you might have missed. Not unlike what my father did in his slide shows.

© George Slade: Lunch with her big brother. Lee asked me, or Dad, or the world at large, if we’d ever seen the local foliage so lushly green as it has been this damp summer. Dad mostly stared at me out of the darkness that increasingly surrounds him. I looked at these siblings and saw 160+ years of seasons, bright and dark, vivid and dimming. Lee still drives. Dad gets confused when I bring him back to the memory care unit upstairs. Twice during brunch he asked Mom where she lives. When Lee left, Dad was still sitting at the table. I was walking her to her car when she about-faced, scooted over to the window, tapped to get his attention, then stuck out her tongue and wiggled her fingers at him. We all get younger with age.

What is next?

I’ve been working with older photographs, my own and others’, to elicit memories and fabricate reflexive narratives that capture my own efforts to comprehend the world through images. I discovered the negatives from a Grateful Dead concert I attended in Maine in 1980, and I’ve made a modest risograph zine with those. I’m also writing notes to a handful of archival photographs from Minnesota that evoke specific thoughts and feelings about having grown up here and in the overwhelmingly nurturing conditions I did. I’m planning to print those images/texts in another risograph project.

© George Slade: Mom was pleased to see Dad looking “so handsome” in his well-worn corduroy jacket, dressed up for Sunday brunch. Worn so well over time, illustrating the value of buying somewhat costly things that last. The jacket and the shirts fit memories more than the present body. The clothes are roomy, like children’s garments bought loose, anticipating growth. Dad, conversely, is shrinking out of his clothes. I was happy to see him in this familiar jacket. And then blown away by the tableau he built on the table in front of him. He was idly fiddling with his place setting, unrolling the napkin, dropping the spoon on the floor, making little adjustments, then hovering his hand over and softly patting the arrangement. Without prompting he explained that this showed two people tucked into bed. His gentle hand suddenly became a soothing touch for a querulous child, a loving approval of a couple’s togetherness. It was a crystalline glimpse into the Dad of right now, precisely fitting himself.

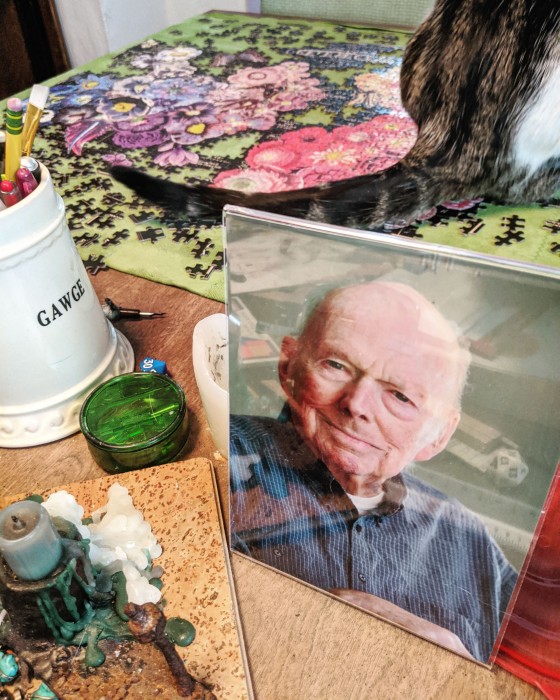

© George Slade: The sustenance of our life these days: Jeopardy! and that British baking show on TV; Milan, inspired to bake nearly every night during breaks in juggling; he and Amory consuming the products almost before they cool; nearly finished the jigsaw puzzle, except for the pieces Willa has ingested, flicked down to Ives, or secreted away under the couch; all four of us trying to avoid spending all our waking hours on our devices, yet thankful for the connections these portals enable. We realize our gratitude to the four-legged animals inside the house and the many winged creatures outside who remind us of free choice and equanimity. Dad regards our circumscribed lives with this bemused, inscrutable expression. How much like his constrained world have ours become? What can he teach us in this extraordinary moment?

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

Review Santa Fe: Ilana Grollman: Just Know That I Love YouFebruary 10th, 2026

-

Review Santa Fe: jessamyn lovell: How To Become InvisibleFebruary 9th, 2026

-

Review Santa Fe: Julia Cluett: Dead ReckoningFebruary 8th, 2026

-

Review Santa Fe: Elizabeth Z. Pineda: Sin Nombre en Esta Tierra SagradaFebruary 6th, 2026