Parker James Reinecker: Pt. 1 – Two Cardinals in the Thicket, Pt. 2 – Desegregation

For the next few days, wewill be looking at the work of artists who submitted projects during our most recent call-for-submissions. Today, Parker James Reinecker and I discuss Pt. 1 – Two Cardinals in the Thicket and Pt. 2 – Desegregation.

Parker James Reinecker is a visual artist, photographer, and educator based in Central North Carolina and Atlanta, Georgia. He is currently working in the Central Piedmont Region of North Carolina. Using various themes and contemporary iconography, Parker’s images and series develop metaphorical narratives through a candid setting, while keeping a focus on human ecology and the identity of landscape– physical and social.

Parker’s work has been exhibited in various galleries, museums, and institutions internationally and in the United States including High Point University, Marshall University, the Colorado Photographic Art Center, The Academy Art Museum, and the National Center for Civil and Human Rights. His work has also been featured in various national and international publications/platforms including C41 and Eyeshot Magazines, Dodho Magazine, and The Photo Review. Parker is an MFA recipient from Savannah College of Art and Design and is a full-time Visual Arts Instructor at Rowan-Cabarrus Community College in Salisbury, North Carolina.

Follow Parker James Reinecker on Instagram: @@in_the_park_

Pt. 1 – Two Cardinals in the Thicket, Pt. 2 – Desegregation

Two Cardinals in the Thicket is a two-part photographic series exploring themes of human ecology, navigation, and how a landscape shapes its own identity. Part I, titled after the project, puts a focus on a lowbrow catalog of a location, like the way one might explore what flora and fauna are in a backyard, investigating our private spaces. The images, taken throughout the Yadkin Pee-Dee River Basin in the Central Piedmont Region of North Carolina, act as a survey of this contemporary landscape. From the days of Reconstruction, Jim Crow, and a sharp class and community divide that exists today– how can the echo of heavy history be conceptually embedded into the land? Influenced by Szarkowski’s ideas of Mirrors and Windows, the images seek to bind documents and poetics, candid and intentional, aggression and subtlety, isolation and connection. The state bird of North Carolina, the Northern Cardinal– symbolic of relationships and lost loved ones…two cardinals, together in the thick of things.

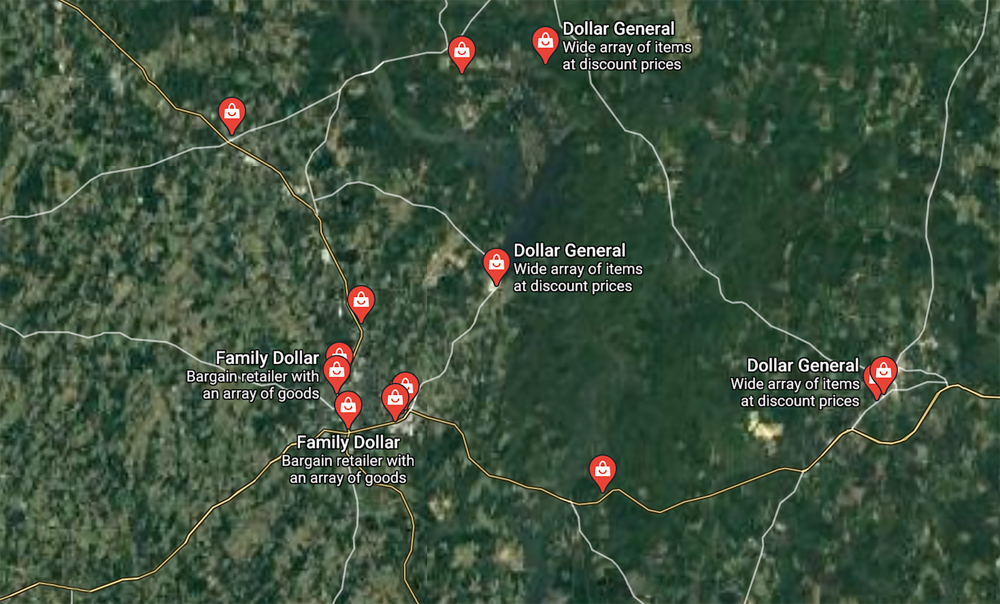

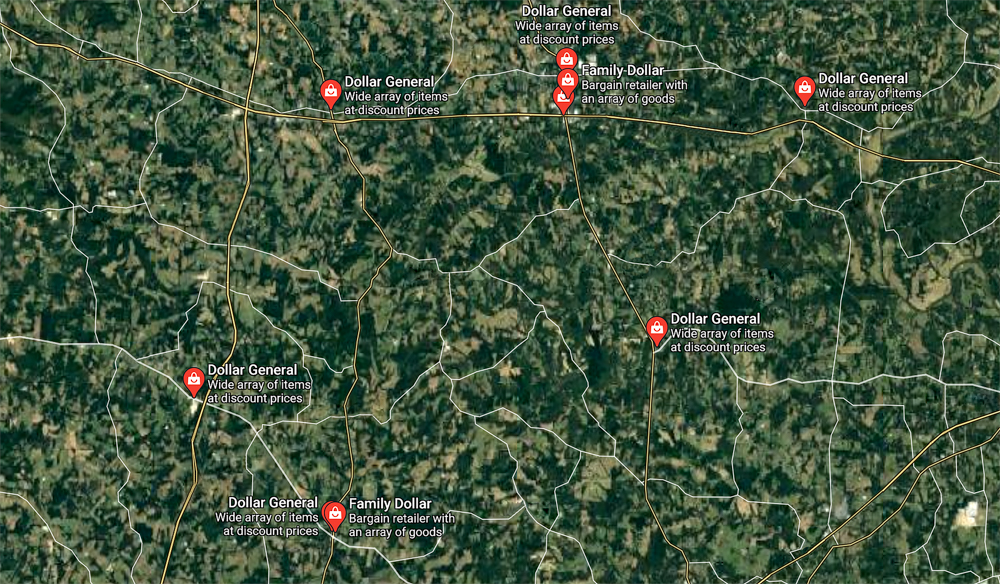

In Pt. 1, titled after the project, breaks away from defining a sense of place. Screen captures of satellite imagery are digitally altered, removing the names of towns and highway markers to define this “social landscape” of class in the rural south by shifting the focus to the dollar stores and their descriptions. Being some of the most populous retail locations in the country, these images aim to place the viewer in a position to navigate this landscape without the necessary resources. Although very different, the “maps” share common features with the “features of the land” working with the photos of river reflections and rockfaces. The rock surfaces touch on the idea of defining an identity through the characteristics of “place” and the natural erosion and changing of space, forming a conceptual relationship with the way the dollar stores change the landscape.

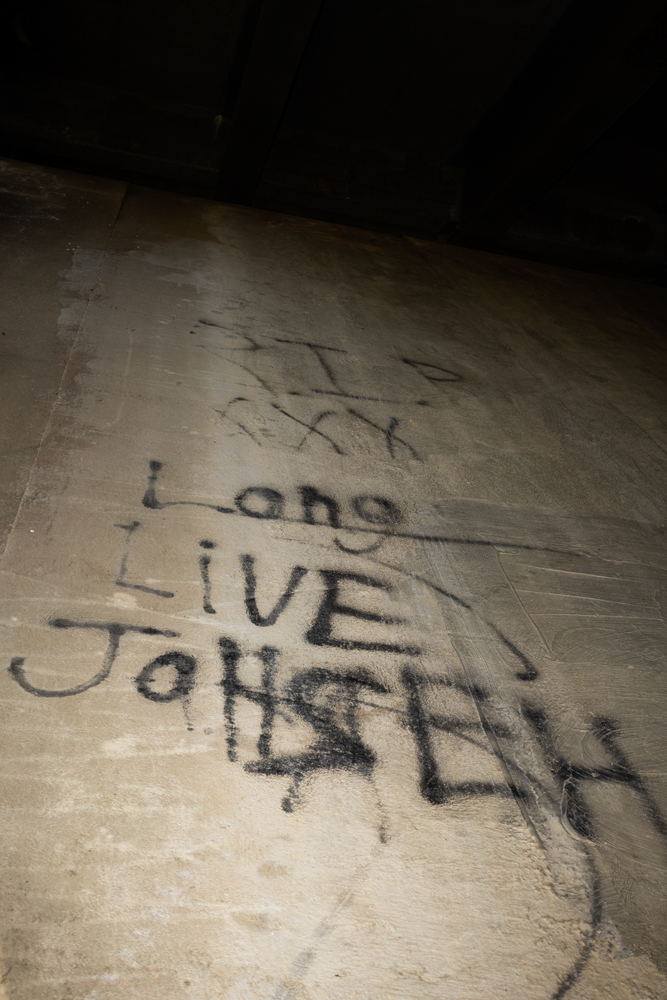

The down-market graffiti and Arborglyphs (markings on trees) relate to this instinctual need to make a mark of significance and permanence. Black and white images, shot on 135 film, layered into landscapes become a small piece to a puzzle and stand for a vague understanding of one’s confinement to a location. The closer interactions with a human element become a moment of intimacy for the viewer. Separating the subject from the background these images work to isolate the subject from their “environment” of the everyday with the use of the flash. Although harsh or disengaged, these interactions act as a pause and share a relationship with the photographic studies of flora. This contrast between the flowers and the more confrontational images of people becomes a conceptual and intimate investigation of personal relationships.

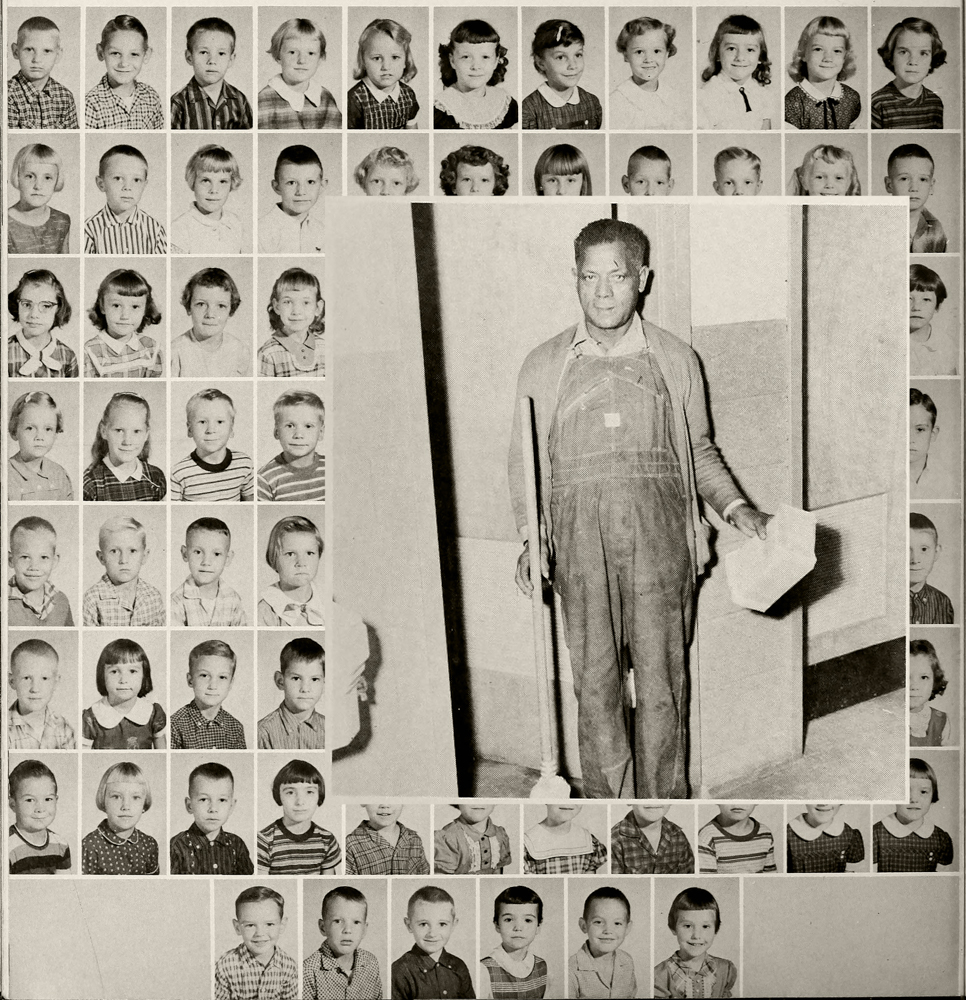

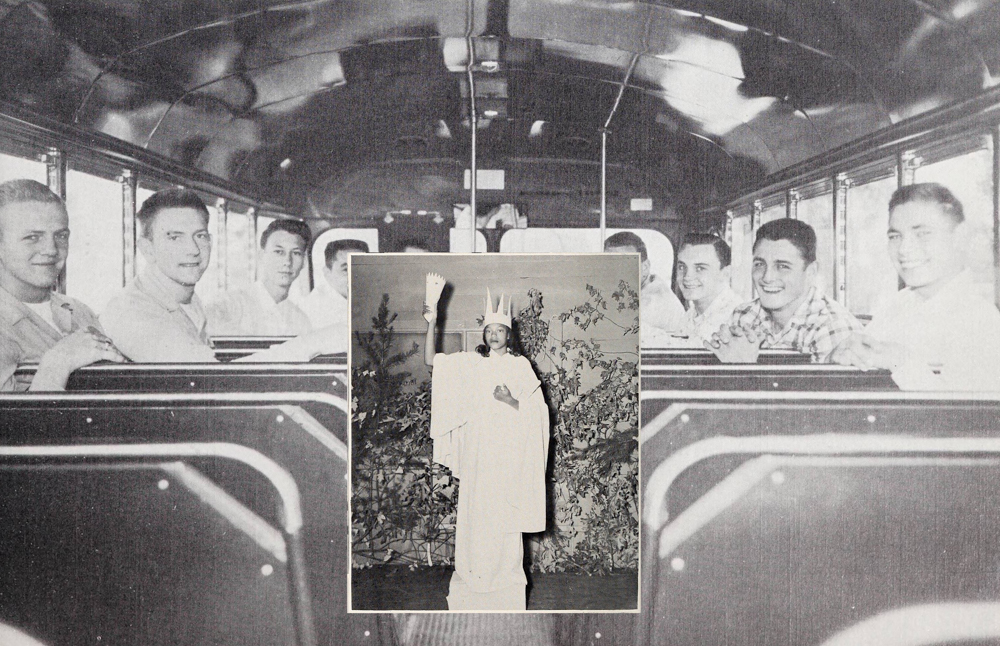

Furthering the theme of the “navigation of space” there is a use of found objects in Pt. 2, titled Desegregation, using appropriated yearbook photos dated to the 1950s, from segregated schools in the Yadkin Basin. Images are collaged together to build narratives, combining these two historically racially divided spaces to desegregate the space. Photographs by unknown yearbook staff place the viewer in the point of navigating designated “white” and “Black” spaces of this region and focus on the awkward nuances of these respective spaces. With this recontextualization and emphasis on visual literacy, the hope is to challenge viewers and equally as important, challenge myself to develop conclusions about how the more contemporary theme of racial and class segregation continues to exist, and is systemically reinforced and taught today.

Daniel George: What brought you to the Central Piedmont Region, and ultimately led you to begin making this work that focuses on the area’s land, individuals, and history?

Parker James Reinecker: So, I knew when I was going for my BFA that I wanted to teach at the college level. Out of grad school, I was beyond fortunate to get a full-time teaching position at a community college about 45 min north of Charlotte, and about an hour south of Greensboro in Rowan County. I love this position because I get the chance to work with such a diverse background of students. I’ve learned and continue to learn how to be an educator in the arts and how for a lot of my students, the ah-ha moment that happens when they realize their personal background, experience and interests are paramount to creating meaningful images. This area is a pretty expansive rural region that for most people, sits in-between two very romanticized ideas of North Carolina. You have the Blue Ridge Mountains to the west, with Asheville / mountain towns and resorts, and then the Coastal Lowlands to the east with like, Wilmington, the Outer Banks… basically what people think of when they think of Nicholas Sparks’ Books.

I had lived in Atlanta for over three years during graduate school and I felt a bit out of my element being a white kid from a blue-collar region in Northeastern Pennsylvania. Race was often at the forefront of the discourse about class and social division in the South, but in Atlanta, there is a primary focus on the history and issues of the city itself. While I was there, I began traveling out of Atlanta to make work, and I felt lost in a sense. I believe that I need to have a relationship in some way with the work I’m making, and being in a new place, I didn’t know how to start. So, I began to go to small county fairs in North Georgia, in the Appalachian foothills. Through this, I started spending a lot of time in towns that had this deep history attached to agrarian issues similar to the way where I’m from in the Northeast had this history with coal.

With moving to North Carolina, to a space and into communities of people with direct ties to the land in some way, shape, or form, I just began and continue to travel and learn as much as I can about this space. And through research and discussions with people in these communities, the history of the Central Piedmont is interesting, especially as this space of “in-between” as I mentioned before, was ideal for travel through the region due to where it sits in the terrain. With that, it was a pipeline of slave transportation from plantations in Virginia to the Deep South. And today you see the divisions in these spaces through a history not only divided by race but through the history of “Old Money” southern families and poor non-landowning whites. This history here is complex and so difficult to begin to unravel, again especially being white and from the North. I notice that this history even here needs to be sought out. For example, I have students who pass by signs of segregation like a bricked-off “once was” entrance on the second story of a theater in their town and they have never thought about that. So, as far as the beginning of these images, I started just making rules for collection and themes in categories of what interested me and began to piece it together in a more contemporary sense. I also started to think about the ways we as individuals look at environments within our personal spaces and apply some of those ideas to the way I was making pictures.

DG: In your photographs that contain people, you either crop out their faces, or position yourself in a way that faces are hidden. Could you talk about your decision to obscure these individuals’ identities?

PJR: So, of course, it is something that numerous photographers, some influences of mine have done before. It isn’t a new way by any means of approaching portraiture, but I started to do this when I was working on a project out along the Route 66 corridor of New Mexico that was focused on some similar conceptual themes that I’m thinking about now in terms of landscape. I would have these moments of interactions with people and conversations, and I would take portraits, but I started to think about the project as a whole and found that there was almost increased value in those images and the other photographs, became more, bridging type of images in a series and I didn’t want that to be the case. I didn’t want to assign a face to a specific place and in a way say this project is about the people because it really wasn’t. So, for me, I just found that the direct viewer engagement with the face was just a touch too much, so I would put the focus on hands, shoulders, tattoos, etc. Maybe this is a side point, but I was making that work in New Mexico and North Georgia, and it was probably in 2017, we were having that conversation about that Lee Friedlander image of his shadow on the woman’s back and how that photograph often gets coined as an “aggressive” image and I was thinking about that idea of attaching an emotional category to photographs and was thinking is that possible, and I still don’t know the answer to that question, but I think that may have inspired a bit of a challenge to work closely in that way.

This project, Two Cardinals in the Thicket, has been a project where I photographed overall very differently than I ever had before. I began breaking rules I made for myself. I really began coming out of a way of working from a distance that I had pigeon-holed myself in with early work in Pennsylvania, New Mexico, and Georgia. I wanted to push those ideas further and work a lot closer than I ever had before. I wanted to step out of my comfort zone in more ways than one. I began simply asking a lot more people if I could photograph them rather than just taking pictures on the street. And they became symbolic of issues that were happening in this space. Like the one in the thrift store in Mt. Gilead, NC, the girl has a #pettygang tattoo and she’s holding a phone, relating to this idea of technology as a distraction in this space. The one image of the man at a knife stand holding a set of brass knuckles relating to the idea of violence. The man (self-portrait) of the lip tattoo that says, “Heat Rock”, this relating to the issue of addiction. Those are just some examples that appear throughout the project so again, for me, in line with what I had mentioned about the work in New Mexico, I wanted the images to stand for something a bit more than just a focus on the individual.

I’m a collector of photographs as well, and it’s funny because since I began working that way, I’ve been attracted to images that do the same and have begun a collection, Matt Eich, Stacy Kranitz, Rosie Brock, and others, of some obscure body parts that I get to look at hanging on my wall every day. I find it challenging for photographers who work that way successfully and make successful images that don’t rely on the face to tell a story.

DG: Tell us about your choice to divide this project into two parts, and how each component contributes to the other.

PJR: So, within Part II- The Desegregation Series, the first collage I made was with this image of a custodian, and the image was simply captioned “Mr. Will”. I was searching for material about some map of some goldmine I never ended up using but wound up stumbling through this database of North Carolina yearbooks. I began to search for schools that were segregated in the 1950s, the first decade of protests in the segregated educational system in the South, and this image of Mr. Will immediately caught my eye. He was standing in overalls outside of a bathroom stall holding a stack of paper towels and a broom. I titled the collage “Mr. Will: Tribute to Ella Watson-16 years Later” because I immediately thought of Gordon Parks’ “American Gothic” photograph. The composition of the image of Mr. Will was so similar, I still wonder whether or not the nameless yearbook photographer knew of the image. The image was dated to 1958 which was pretty much in the middle of the Civil Rights Movement and I was so intrigued by his overalls. With all of the time I spent in Atlanta, I thought of the Civil Rights Activist Hosea Williams who was known for his overalls, symbolic of the Black working class in the agrarian South and I thought “was Mr. Will aware of what was happening then?” Mr. Will was the custodian at a white school, for this collage I simply just set his photograph on a background of young, white, elementary school faces. This is the only collage in the series that isn’t “desegregated.” Then as the project went on the collages would end up becoming more complex.

I received numerous criticism and feedback regarding whether or not to separate the series. People have said they feel that the images are too different, and “they don’t connect” and then, on the other hand, I’ve had people say, yes, “the difference in images builds a stronger relationship between all of the images in the series.” I think whether it’s “right” or “wrong” is just so subjective. I think they can be displayed separately but also together. Conceptually, in my opinion, and I would never tell people what to think, the collages talk about a part of the same history, just a different part of the timeline of the space. I was also asked the question recently for an exhibition of the work at Marshall University if my privilege or recognition as a white northerner was built into the work, and honestly, I’m not sure… I’m sure it is somehow, but maybe not directly put into the work. I think it is more subtle than that. I just have such an interest in the history of this place and spaces like it, and how this history has and continues to affect the trajectory of this history of these places. What is “truth” in a photograph? Can an image be “true”? Again, I don’t have the answers to those questions, but I think if I’m going to spend my time working in a space, or a location, whether I have a direct connection to it or not, I owe it to that space to learn the history and do the research. Topics of race, segregation, and class are things I never learned about in social studies class in grade school, especially going through a Catholic school education. Even where I went to undergrad was a small Catholic college in the North and in that pursuit of my BFA, those conversations weren’t really happening there in the art program. It wasn’t until I moved to the South and students across disciplines of artmaking, at numerous institutions–even outside of higher ed. in different community initiatives and groups… that was the conversation that was happening, and I just felt it was important.

DG: In this series, satellite imagery and historical photographs/drawings accompany your own photographs of people and places. Would you describe your interest in this process?

PJR: The Satellite imagery was a wild thing that started as I was traveling around. I noticed there was so many Dollar Stores that literally dotted the Yadkin-Pee Dee River Basin and actually, all over the rural South… literally everywhere. Although it is a little bizarre, it stands for a larger problem about access to food in these rural locations. The Dollar Stores become a band-aid on a gunshot wound and offer no sustainable solution without playing into a larger conversation about equity in nutrition. Early on in this work, I wanted to see where the dollar stores were, how many were in a certain location, and how far apart they were.

Calling a spade, a spade, oftentimes people who frequent art galleries or engage with art in a critical sense are often aware indirectly of social issues, or artwork engaging such topics. I began to remove road and town names and highway markers so the only points of navigation left are these dollar stores that spot the satellite image of this landscape…(literally the Google Maps app). All this attempts to put the viewer in a position to navigate this landscape without any vital resources, only the dollar stores as formal landmarks. One thing that’s interesting about how that all came about and how that began to fit in with the work, I was photographing close-up textures of rockfaces and formations, and early on I mentioned how the lines in the texture of the rocks mimicked the lines of the roads in the maps… a friend of mine, fellow photographer and educator Carlos Nuñez then mentioned to me about how the images of the rocks were symbolic of the natural erosion of the landscape, and how it stood for the space changing over time. I loved that point and had never thought about it in that way, the further connection between those themes, how the use of technology to “view” and “navigate” this changing landscape, and then how this whole space is always naturally changing… just thought it was an interesting point.

DG: You write that this series explores “themes of human ecology, navigation and how a landscape shapes its own identity.” In what ways do your photographs accomplish this?

PJR: I feel I mentioned this a lot, in so many different ways in questions before, but overall, for Two Cardinals in the Thicket, I began photographing different elements of the environments I was traveling, a space in which I now lived, in North Carolina. I began to develop rules for the images I was making or better yet, rules for the way I was photographing them. Like the flowers were photographed a certain way, my interactions with people a certain way, more formal/cinematic landscapes a certain way, etc… I love rules in art making. And all of this kind of came about for this project, thinking about my grandparent’s house and how they used to keep a set of binoculars by the window at their kitchen sink looking out to their backyard. They lived in a very old-school suburban, neighborhood where the houses were close and you could cut through backyards to get from block to block. They would use that pair of binoculars to survey the flora and fauna that inhabited their direct environment. So, thinking about that lowbrow, everyday study of this landscape and how it becomes almost circadian. I was just thinking about we are constantly studying our everchanging spaces was how this overall documentation of this landscape came about.

The title, Two Cardinals in the Thicket is also a play to that in a way but also speaks to more poetic symbolism that we associate with our environment. Cardinals, the state bird of North Carolina, often can come to symbolize a loved one who has passed away, and seeing one is often associated with good luck or that loved one coming to visit you… unfortunately, (spoiler alert), throughout the series, seeing these cardinals never happens. In a gallery exhibition, the images of flowers, and the time of day of those prints get darker as they are hung in the gallery space. The closest you come to see the “cardinals” is a play on the eye with two separate photographs of two roses hung side by side, printed so dark you have to almost squint to see. Again, inviting participation from a viewer in a way, it’s almost like with the implication of the title. The viewer begins searching this landscape for a sign or symbol that isn’t there. “Two Cardinals… together in the thick of things.”

Speaking about the way a show of the work is hung– the work is often hung staggered and in a sense salon style. This I feel reinforces the read of the relationship between the photographs and how a viewer experiences the work. For example, there is a large-printed photo of a Black Swallowtail Butterfly against the white sand background, what appears as small pebbles are actually bullet fragments as this white sand background is actually a shooting range. The way the rest of the images are hung around this image is meant to loosely mimic the way you may watch this butterfly pass in your backyard, floating through.

DG: You also mention that you “seek to bind documents and poetics, candid and intentional, aggression and subtlety, isolation and connection”. In what ways do you feel photography is best equipped to confront heavy, embedded histories in the land and culture?

PJR: Early on in my photographic education, I remember learning about John Szarkowski and reading his essay accompanying his “Mirrors and Windows: American Photography Since 1960” Exhibition. I remember thinking about this show and this essay and about how he says basically, of course, there is gray area when categorizing photographs into Windows, an extroverted look into a different experience (exploration) or Mirrors, an introspective investigation (self-expression). So, if I put the weight that I think I do into this sentiment, I really have to break it down, is the image a strict document or is it a poetic point of view, or both? Can I form a relationship between very different or for example “aggressive” and subtle images? Can the images work to connect, the subjects, viewers, myself, to the land? Or work to isolate, remove or other? Can they be both? This is where I feel the project, for me ends up with more questions than answers. It is a space where I have never been before with any long-term project I have ever done, and I’m actually super into that.

As I mentioned before, with this work, a goal for myself was to reach outside of my comfort zone when it came to image-making and I feel like I have achieved that. Making Two Cardinals in the Thicket and some of the new work I have been doing that has come out of this project have just been so refreshing. I feel there’s always more to learn from image-making, whether it be through the art-making itself or the research. I definitely don’t pretend to have anything close to all the answers and I have to say, that in itself is pretty awesome.

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

Ricardo Miguel Hernández: When the memory turns to dust and Beyond PainNovember 28th, 2025

-

Pamela Landau Connolly: Columbus DriveNovember 26th, 2025

-

KELIY ANDERSON-STALEY: Wilderness No longer at the Edge of ThingsNovember 19th, 2025

-

Jackie Mulder: Thought TrailsNovember 18th, 2025