Jessica Burko: Fractured & Found

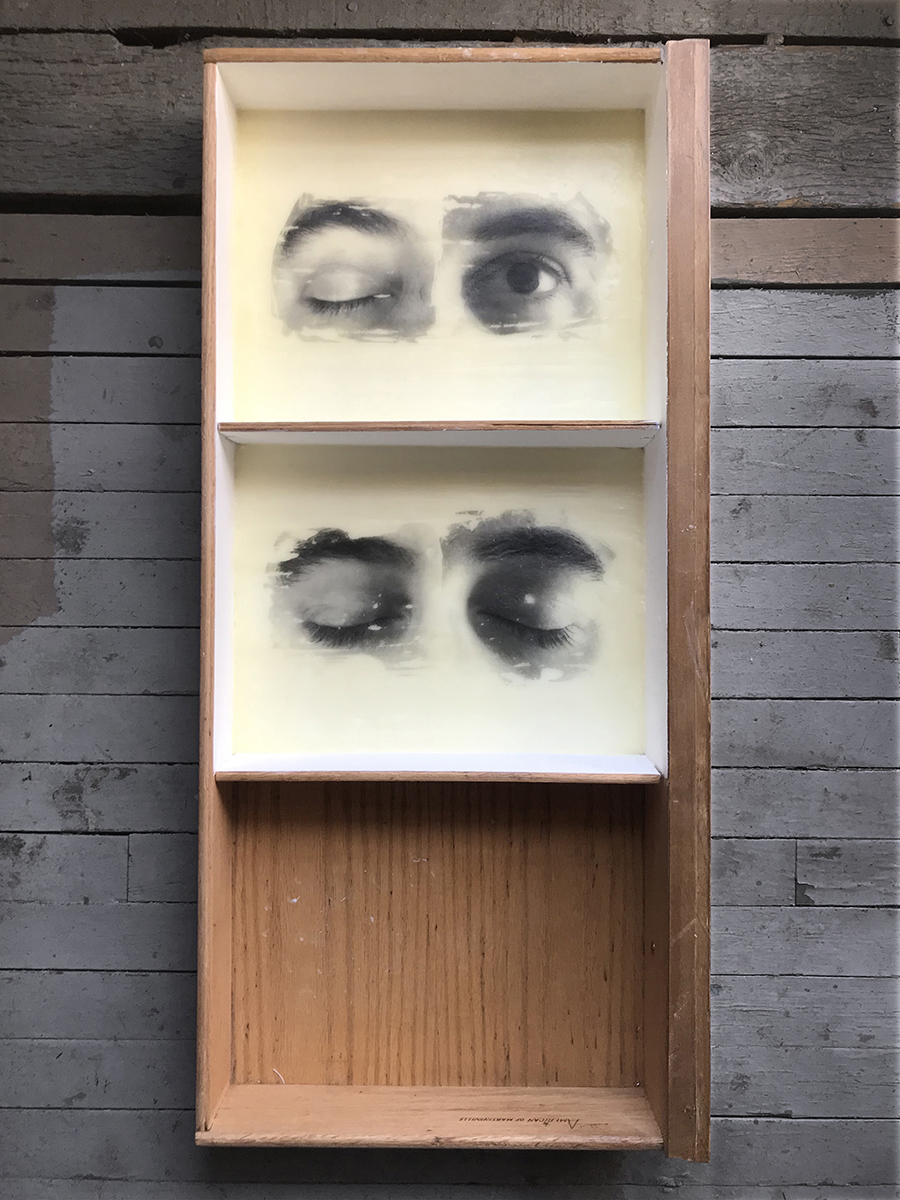

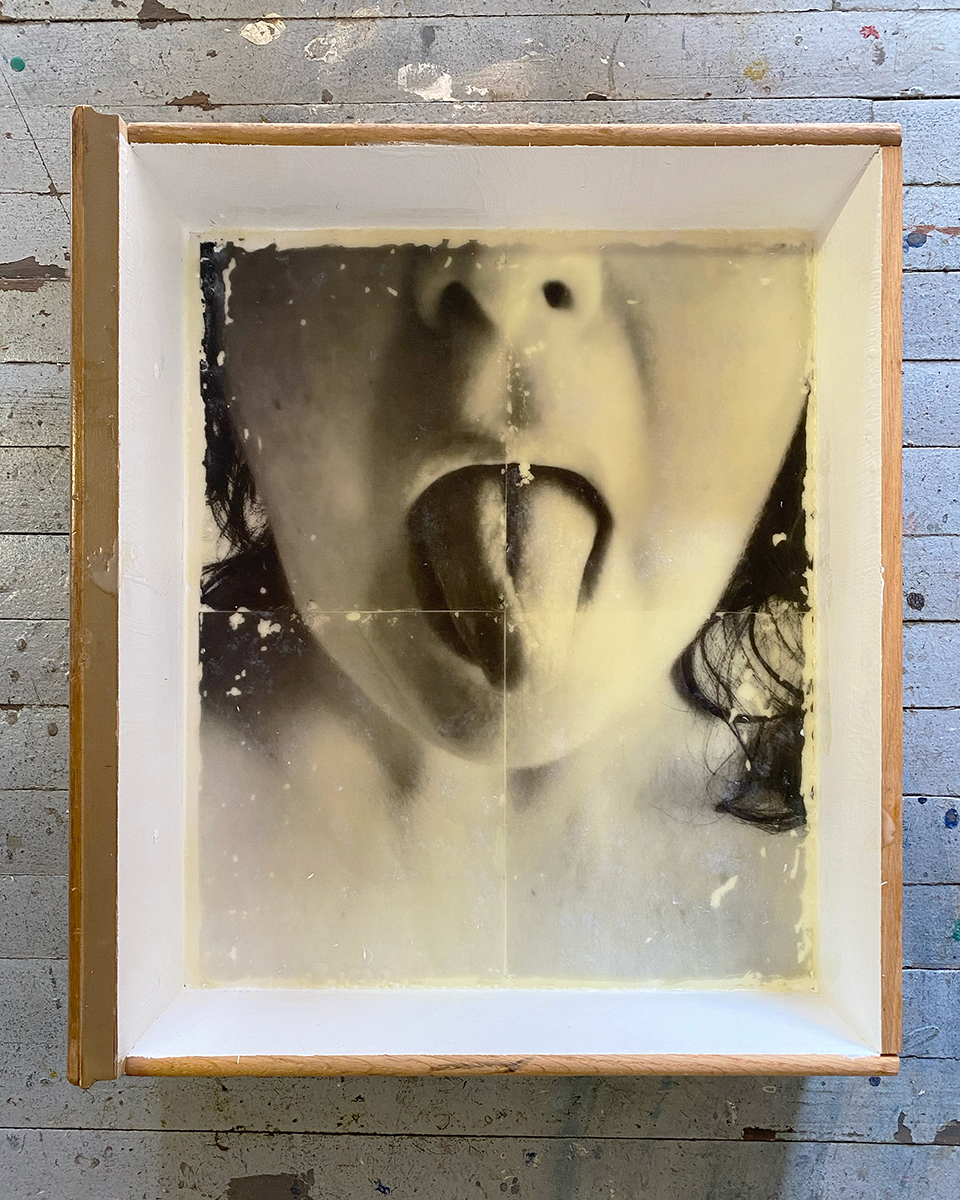

©Jessica Burko, Fractured & Found installation, 2022, image transfers with encaustic and found drawers, Beacon Street Gallery, the Brookline Arts Center

Artist. Mother. Wife. Photographer. Daughter. Curator. Jessica Burko holds all these titles simultaneously. In her exhibition Fractured & Found, Burko analyzes the affects of women who are expected to carry many different expectations and identities. The resulting images cast a harsh light on the way society has forced women into these roles.

Using found objects and encaustic medium, Burko utilizes imagery of the disjointed body to explore the idea of compartmentalization, allowing viewers to see themselves in her work and consider the own ways they have created these separate “identities”. The emotion Burko achieves through this exhibition is truly haunting yet sheds a beautiful light on the ways we split ourselves apart.

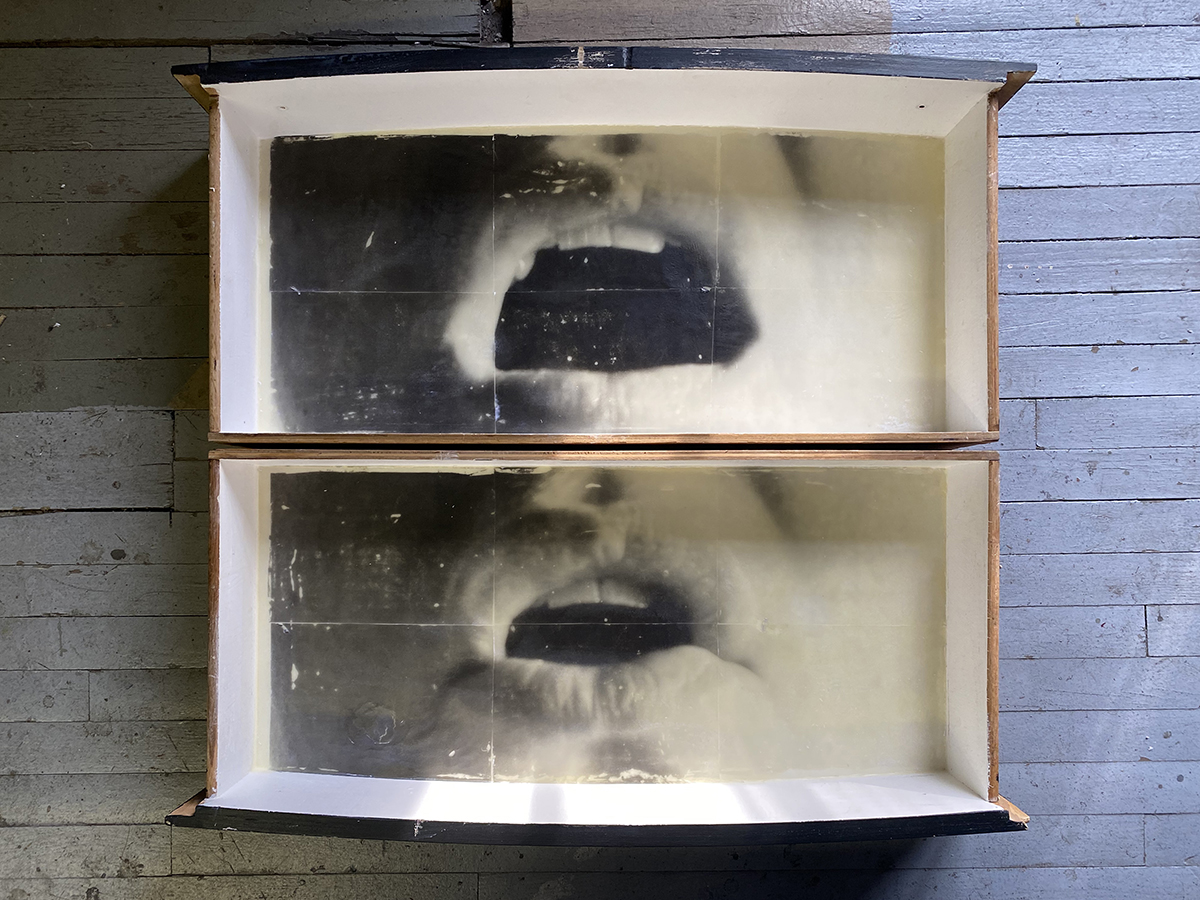

©Jessica Burko, How Do You Really Feel (triptych), 2022, image transfers with encaustic and found drawers

Jessica Burko has been an exhibiting artist since 1985 and has displayed work in solo and group shows throughout the United States including New England exhibitions, Fractured & Found, 2022, an installation at Beacon Street Gallery, an annex of the Brookline Arts Center, Quiet/Loud, a 2018 solo exhibition at ArtProv Gallery, Providence, RI, a 2020 solo exhibition at the Shelter In Place Gallery, Boston, MA, and inclusion in 5 Years of Aspect Initiative, 2022, at the Danforth Museum, Framingham, MA. Her work has been reviewed in the Boston Globe, Art New England, and Artscope Magazine. Burko is originally from Philadelphia and currently lives in Boston, Massachusetts. She holds a BFA in Fine Art Photography from Rhode Island School of Design, and an MFA in Imaging Arts and Science from Rochester Institute of Technology.

In addition to being a practicing artist, Burko is the Creative Director at the Photographic Resource Center, Cambridge, MA. She is also an independent curator with more than thirty exhibitions produced since 2000, and her professional background includes the position of Gallery Director at Stonehill College from 2000-06, from 2007-14 she held the position of Executive Director of the artist collective Boston Handmade, and from 2016 to 2019 she was the Marketing Director at Kingston Gallery. Burko’s work in the arts community allows her to foster and strengthen connections between working artrepreneurs. She supports artists in achieving their creative and professional goals through lectures, workshops, and partnerships with organizations such as ArtsWorcester, Worcester, MA, Mass MoCA’s Assets for Artists Program, North Adams, MA, and the Atlanta Photography Group.

Follow Jessica Burko on Instagram: @jessicaburko

©Jessica Burko, Fractured & Found installation, 2022, image transfers with encaustic and found drawers, Beacon Street Gallery, the Brookline Arts Center

Fractured & Found, a photography-based mixed media exhibition by Jessica Burko, is being presented by the Brookline Arts Center (BAC) at the Beacon Street Gallery, 1351 Beacon Street, Brookline, MA. The exhibition is on view October 1, 2022 through January 15, 2023. Beacon Street Gallery hours are Monday-Saturday 11:00 am-7:00 pm and Sunday 1:00-5:00 pm.

The exhibition presents an ongoing series that combines photography and encaustic medium inside reclaimed wooden drawers. Thirteen of the drawers contain photographic images of primarily fragmented self-portraits transferred into the encaustic surface. The remaining drawers come together around them pieced into towering and teetering structures. In addition to the sculptural works in the exhibition, Burko includes Origin Story Portraits as archival pigment prints of the drawers as found on curbsides throughout the greater Boston area.

Fractured & Found

Photographic images inside found wooden drawers.

Structures towering and teetering, leaning, and standing.

Photographs that are pieced and fragmented, faded, and yellowed.

Fractured self-portraits surrounded by containers of abandoned voids.

Fractured & Found makes connections between interior being and

being on display, creating emotional divisiveness while in demand

by conflicting forces. Searching for balance between selfhood,

motherhood, working, and rest, feeling overwhelmed and exhausted

by compartmentalizing and forcing a fit into each role.

Through the juxtaposition of isolated compartments of broken moments

and emptiness there appears to be room for breath, for rest, or perhaps

they are intervals yet to be filled. The absence of image hints further at

a disjointed existence.

Incorporating found materials helps me feel grounded in what’s real

and what exists outside of my head. The drawers symbolize not just

boxes I’m trying to fit into, but also spaces that were once private,

now revealed and put on display. Much of my work grows out of the battle

between yearning for one thing but doing another. Embedding the images

into encaustic is like sealing time in a bottle, making it quiet and still,

like secrets hidden beneath folded cotton. -Jessica Burko

©Jessica Burko, Fractured & Found installation, 2022, image transfers with encaustic and found drawers, Beacon Street Gallery, the Brookline Arts Center

Kassandra Eller: To start off, I just want to say this project is mesmerizing. I find myself continually going back to each piece, and finding something new to reflect on. I would love to know how the idea for this project came about.

Jessica Burko: Thank you for those kind words Kassandra. My work has been autobiographical for many years and this series is an extension of that theme. When I had children, I continued working as a visual artist, educator, curator, and arts administrator. As the years progressed and life became progressively more complicated and hectic, I felt myself managing multiple identities, fracturing in a way, into each role as a way of inhabiting them and their disparate responsibilities.

I began collecting found drawers because I saw them everywhere, thought they were beautiful, and felt like I could repurpose them. In addition to being a visual artist I’m an avid knitter and for many years I have created wearable accessories from post-consumer yarn. It became a bit of an addiction and as the bushels of work grew, I sold them a few times a year at craft shows where I used the drawers as part of my booth display. I also made some bookshelves and used a few for storage.

The more drawers I collected the more I started to think about their history and stories they held, the identities of the people who used them, and what might have been held inside. In 2015 I began working with image transfers onto encaustic and found wood, after developing a large body of work entitled Quiet/Loud I began to see the drawers as potential vessels for my images and as building blocks to create narratives. As life continued to churn, I began the work that is now Fractured & Found, then the pandemic hit and worlds collided, emotions heightened, and the meanings of the inhabited and vacant drawers transformed into vehicles for exposing what’s just beneath the skin.

KE: How did you go about choosing the drawers that should be used in Fractured & Found? What qualities were you looking for when you would find the drawers?

JB: I’m more particular about the drawers than one might think. While I will quickly pull over the car for anything drawer shaped, I only take well-made wooden drawers, no particle board, and I prefer drawers that look like they are from the early to mid-twentieth century. They seem to be hauled from basements and attics, and I will only take drawers that are not part of a functioning piece of furniture in case someone else wants to use it for its intended purpose.

The influence of found materials in my work goes beyond structure. The weight of the objects, the smell, texture, and age, lead me to personify them and imagine their life before being cast-off. They have distinct personalities that lead my imagination to drift to social-historical context of their time and the collision of past with present. The unwanted aspect of the objects represent life disappeared and I’m filled with family narratives of evacuation, forced or chosen, and whispers of escape united with emergence and becoming free. Sometimes a drawer is just a drawer, but sometimes it can be much more than that.

©Jessica Burko, Fractured & Found installation, 2022, image transfers with encaustic and found drawers, Beacon Street Gallery, the Brookline Arts Center

KE: The way you have chosen to exhibit these works is stunning. Would you elaborate on how you chose which images to use in the drawers and how you concocted these elaborate exhibition displays?

JB: The images in this series are primarily figurative, revealing isolated parts of the body. The visual fragmentation is a way to emphasize the idea of being pulled in many directions, feeling disjointed, and incomplete. The seemingly detached mouth is included as a strong symbol of emotion, and all but one image, of a foot, are self-portraits.

Installing the drawers is a big part of the work and every installation is site specific; no two arrangements are alike, and I create the structures in the space without preplanning. It’s an organic process and feels like an evolving puzzle with many possible configurations, and the method of installation feels like play, like building towers with blocks. The proximity of images adjacent to hollow drawers also suggests non-linear narratives and is intended to lead viewers into the many possible connections, guided by their own life experiences.

KE: In this project, you utilize an encaustic medium. How did this process help further Fractured & Found, in your opinion?

JB: I’ve long enjoyed experimenting with mixed media, and as a photographer, image transfers have been an integral part of my process since taking a printmaking class with Accra Shepp as an undergraduate at RISD. For many years I transferred photographic images onto handmade paper, and in the early aughts I took an encaustic workshop with Tracy Spadafora who introduced me to the technique of image transfers into encaustic medium. This changed how I experienced my photography, it encourages a longer, slower process which slowed down my thought process and led to more developed bodies of work.

There was also a shift in my ability to present the work. Since it was an archival process, I no longer had to shield my images beneath glass, and this made a more direct and tactile connection with viewers. I also began to view the encaustic, a wax-based medium, as a way to seal in the fervor of emotion expressed in the images. Much like using wax in the preservation process of vegetables, as the medium cools, it forms a protective seal and stops any process of degradation and began to feel like a healing process for me.

When working on the pieces that became Fractured & Found, the meditative many-step process of building up the wax surface, flattening it to a glass-like consistency, and transferring the images with force and attention to each part of the surface, helped me slow my thoughts and more fully inhabit my identity as an artist. On the one hand, this felt freeing, but on the other, it emphasized the daily shifts I had to make between identities and intensified the need to convey the experience of living as a fractured person pulled and pushed into boxes that often didn’t fit.

KE: In these images, I noticed that we never see a full face looking at us rather we see parts of the body that have been separated. Why did you choose to “conceal” the face from the viewer and break up the body in this way?

JB: When I initially began making work inspired by personal history and nightmares, I used friends as models and referred to the work as “portraits of self” rather than self-portraits. For the photo sessions they wore my clothing and a wig that looked like my hair. Not photographing myself made it feel safer to tell my stories. Using the guise of another person was a way to protect myself and disassociate from revealing what was under the surface.

Everyone hides parts of themselves from some people, and other parts from other people, and likely some parts even from themselves. With the intensely personal work in Fractured & Found I wanted to make it accessible and relatable so viewers could enter the work and have their individual experiences. Not including details of my face is a way to de-specify identity and allow others to see themselves into the work.

In speaking with people about this work, women and mothers in particular have felt the strongest connection. The modern-day concept of “doing it all” was ingrained in women of my generation through the women’s movement of the 1970’s. Not only were we taught the empowering lesson that we could do it, but also that we were supposed to do it all. In making that happen we became empowered in a new way though we were, and are, still expected to be the primary caregiver, to project manage the household, all while living up to social media standards. The pressure is severe, and if all is going to be done, it might leave is feeling broken into different parts like a mouth making sound, a hand grasping at the intangible, a foot trying to gain stability, and a head holding a brain spinning before it shatters.

KE: To conclude I would like to ask what is next for you. Is there anything you are currently working on?

JB: Isn’t that always the question? As I see it, having a show isn’t the culmination of a body of work. It’s just one step in the development of the work. Generally visual artists work in a vacuum. We close ourselves in our workspace and only discuss our work with others at rare opportunities, like showing the work in public. I find that seeing my work out in the world allows me to have a different vantage point and inspires me to continue growing which will lead to an inevitable shift. For now I would like to bring Fractured & Found to additional venues along with new images and fresh installations, continuing a dialogue about the work, and enjoying the process of making my art.

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

Amy Friend: FirelightFebruary 25th, 2026

-

Jonathan Silbert: InsightsFebruary 19th, 2026

-

Olga Fried: Intangible EncountersFebruary 18th, 2026

-

Anne McDonald: Self-PortraitsFebruary 17th, 2026

-

Review Santa Fe: Elizabeth Z. Pineda: Sin Nombre en Esta Tierra SagradaFebruary 6th, 2026