Photographers on Photographers: André Ramos-Woodard in Conversation with Prince Varughese Thomas

Over the next two weeks, we are sharing some of our favorite Photographers on Photographers posts. Enjoy! – Aline Smithson

I remember taking Color Photography sometime in undergrad at Lamar University. I don’t remember if I was a sophomore or a junior, and I don’t think that really matters, but I do remember that it was a class I was very excited to take. I’m not gonna lie—I had been taking pictures for a little bit longer than some of my classmates, so I felt like I had a good understanding of photography in comparison. Anyways, I vividly remember thinking that I knew what I was doing going into this class.

Prince Thomas had given us a supposedly simple assignment, of which was to take one picture for each color on the color wheel. I did just that; I went out and found these colors in nature or my everyday environments, and I simply photographed those colors. Of course, I tried to make visually interesting photographs each time, but I wasn’t focusing as much on making good photographs as I was focused on completing the assignment: highlighting a specific color in each photograph. When critique day came, we all presented our work like normal—we pinned our printed images to the wall and briefly described the choices we’d made in our artwork. Prince was abnormally quiet during this, but I didn’t think much of it at the time.

At the very end of our small presentations, Prince stood up in front of the entire class and stared at us for a second as we sat in our seats. Reaching into each of our souls, he opened his mouth, and out came, “I need more from you all”, in the most serious tone I’d heard from him yet. It wasn’t mean or ridiculing, but it was sincere and stern. I had never felt that before.

These words changed my entire life. For the first time in art school, I wasn’t simply praised for having good work or told how specific work could be improved. It felt like I was being told that I had more potential to unlock inside myself. I could make art that was even better than I anticipated, but it was up to me to uncover that.

Prince Varughese Thomas is an Indian American immigrant, partly raised in India, and naturalized in the United States. Code switching between communities has been a consistent aspect of his life that has allowed him to recognize and explore various aspects of culture through his art. This multicultural experience through his formative years to adulthood has directly affected how he looks at society and attempts to examine places worthy of exploration and critique to raise larger questions about culture through his art. With an educational background and degrees in both Psychology and Art, the various interdisciplinary projects Thomas investigates speak about contemporary society through an array of themes.

A winner of Time-Based Media in Art Prize 7, a Texas Biennial Artist, an Andy Warhol Foundation Idea Fund Recipient, a Houston Center for Photography Fellowship Recipient, and a Joan Mitchell Foundation Emergency Grant Recipient, Thomas has presented his work in over 250 solo and group exhibitions at numerous museums and galleries, and is in various public and private collections.

Thomas received his B.A. in Psychology from the University of Texas at Arlington, and M.F.A. from the University of Houston. He is currently a Professor of Art at Lamar University.

Follow Prince Varughese Thomas on Instagram: @princevthomas_art

André Ramos-Woodard: I gotta say—I’m eager to pick at your brain, especially since you were my teacher before you became my friend. I think it’s really important that we get to know you as a human, not just an artist. So, I’ll start with the basics; Can you tell me about yourself? Where are you from? What do you do?

Prince Varughese Thomas: Wow. Ok… Here’s a shot at summing up 53 years in a couple of paragraphs… lol.

I am an immigrant. I start with that because immigrants have become villainized in our political/cultural climate for some time now and I think it’s important to let audiences know that I too am an immigrant. How they view immigrants is how they should view me. How they treat immigrants is how they should treat me.

I grew up between a small little village on the Southwest tip of India in the state of Kerala and Dallas, TX. I would in essence go to school in both countries, back and forth, until I graduated high school. This experience formed the foundation on how I look at culture with open eyes as source material for my art.

I learned Photography (Develop/Print) in 7th grade. It’s sad that many school districts have limited their Creative Arts Programs. When I was going to public school, kids could have experience in theater, orchestra/band, and visual art. It was just part of the curriculum.

Now, I am an artist and Professor of Art at Lamar University.

ARW: YES. If only readers could see how hard I’m snapping my fingers in excitement right now. So, when was the moment you decided to become an artist?

PVT: I am not sure I ever consciously decided. I just kind of traveled roads that interested me. I started taking photographs when I was eight years old. I still have my first camera. A Kodak Instamatic X-15F. But when I entered university I just took courses that I wanted to learn more about. So I was a Philosophy Major, History Major, Computer Science Major, and finally I got my undergraduate degree in Psychology from the University of Texas @ Arlington. In my last year of college, a friend suggested that I should take an Art class before graduating. That’s when I took my first university Photography class and I was hooked. Although I got a degree in Psychology, I stayed to take a number of photography classes.

I then applied to graduate schools to study Art but was rejected by all of them. I really didn’t have an art background like most BFA degree students. I just knew I loved it. In hindsight, I wasn’t ready for graduate school but I didn’t know any better so I begged my way into the program at the University of Houston and busted my arse to simply catch-up to my peers. The beauty of that story is that the University that initially rejected me, hired me as a Visiting Assistant Professor right after I graduated.

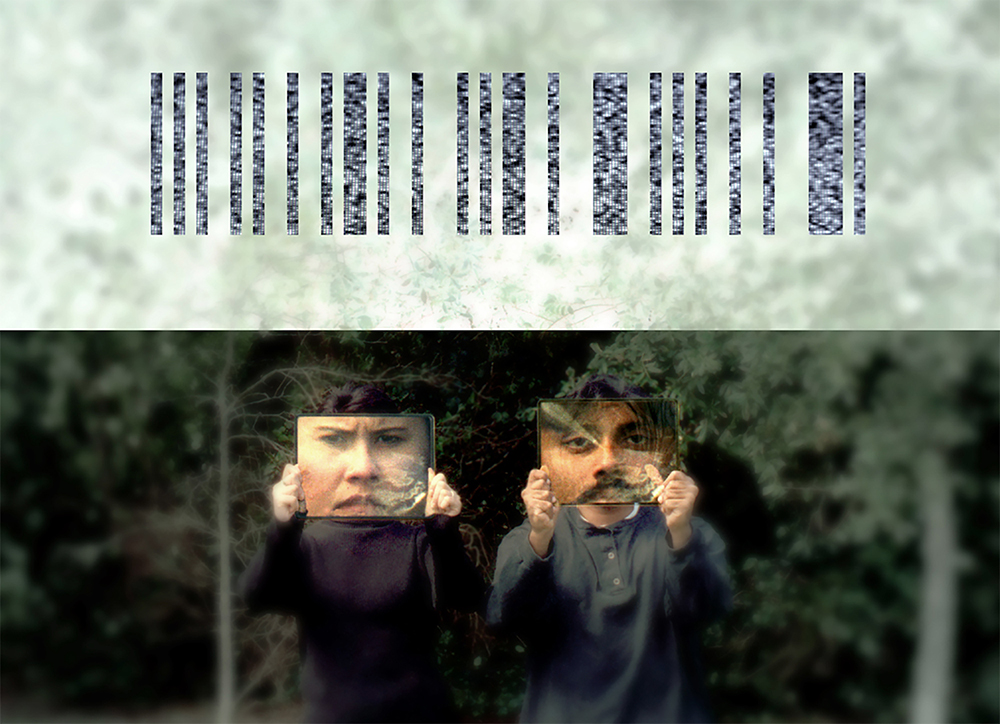

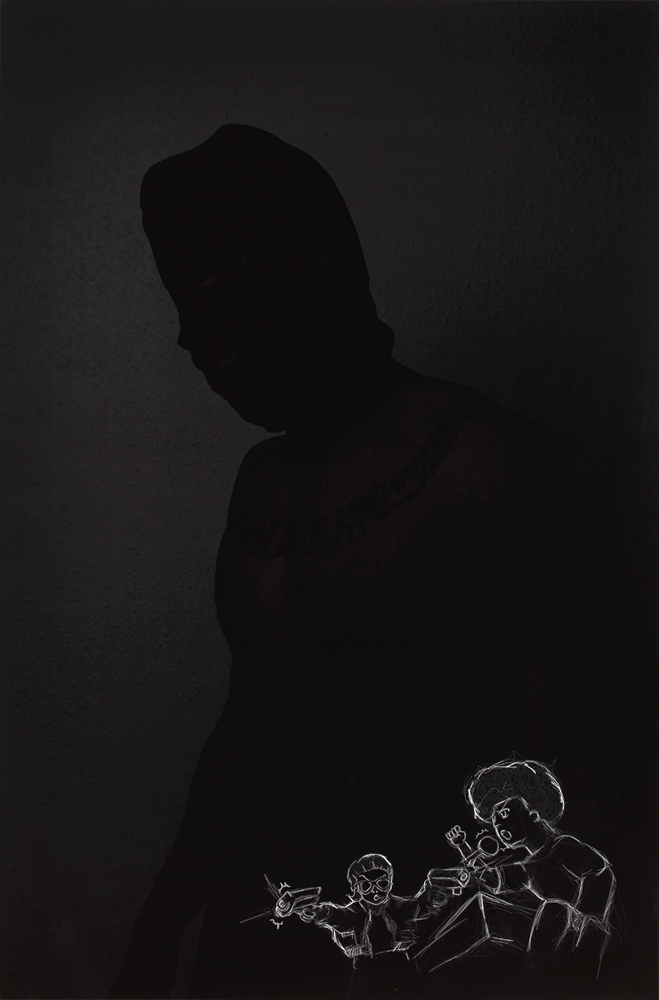

© Prince Varughese Thomas, Ancestors I, from Ancestors Series, Pigment Print on Metallic Paper, 2017

ARW: Damn, Prince. It’s the perserverance, for me. I think it can be pretty easy to feel defeated after grappling with the subjectivity of art school, so I’m glad to know how beneficial all that hard work you did (and continue to do) was for you.

I think one of the first times I saw your work outside of school was when Jen and I went to FotoFest in Houston some years ago. Amidst the abundance of images we saw, we stumbled on your work from Ancestors Series. Prince, that work absolutely took my breath away. It gave me insight to your life and emotions in such a unique way, and I found each piece so aesthetically captivating… I mean, I just fell in love with it.

Did making that work change you or help you in any way? What did that body of work do for you?

PVT: Thank you for your kind words about my work. I think all our artwork helps us grow in some way emotionally and intellectually, if we are open to it.

That work was kind of a culmination of a number of things that had happened in my life. When I was 32, I became the primary care-giver for my parents, moving them from Dallas to live with me in Houston. They both fell ill at the same time and could no longer look after themselves. It was a difficult responsibility but one I chose to take on. Years later, my father passed which led me to exploring the subject of death, grief, and mourning through my familial roots. Ancestors, along with several other projects, comes from those explorations.

ARW: Why do you think artwork like this—artwork that is personal, and relative to a unique experience—is important?

PVT: I would like to rephrase your question just a bit to “why do you think artwork that the artist gives a shit about is important?” I say that because the beauty of the art world is that it allows for all types of art including works that are very personal and works that are much more about formal problem solving. There is room for so much under the “Art” umbrella. There is a beauty in that when you think about it. But the most important thing is to “give a shit” about what you are making. To be sincere, even if your subject is about being insincere or “f*cking with the viewer”. So many artists when they are starting their careers are looking for ‘insta-fame’ versus just putting in the time to find their authentic selves. And sadly, so many drop out because they never get the perceived recognition they desire.

I have a friend/mentor – he is in his 70’s now and his work-ethic blows me away. He has never received any major recognition for his work. But he gets in the studio every day because he loves the act of making. EVERY DAY. That takes a lot of passion for what you do and perseverance in the face of adversity to keep your studio practice up for that long with no external benefit. I mean think about all the people you went to school with who no longer make art. It’s not anything against them – Life gets in the way. But you have got to ‘give a shit’ to keep your art practice up. That should be what drives us all. Now, hitting the ‘art-lotto’ would be great too but let’s face it – the majority of artists will never receive any attention for their work. The art game is corrupt in my opinion but that’s for another conversation over a stiff drink.

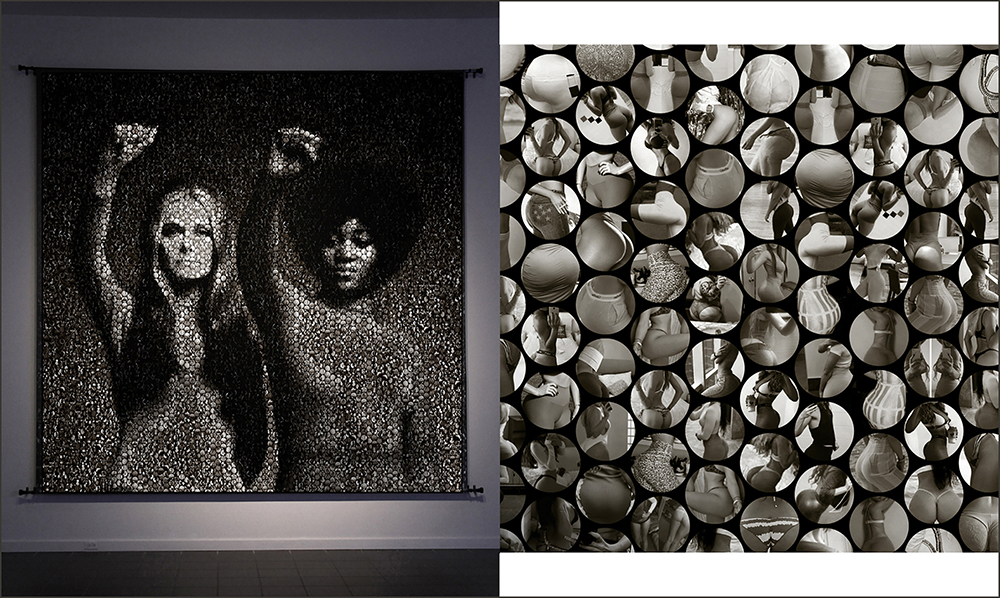

ARW: How do you use your art to fight against systems of oppression? I mean, I see it blatantly in pieces like Body Count and Feminism in the Age of Belfies, but honestly as people of color, almost everything we do to liberate and enjoy ourselves fights against systems that weren’t built with us in mind. I’d love to hear your thoughts.

PVT: Good question. In my opinion, all art is political. It just so happens that I use culture (the times in which I live) as my ‘still-life’ subjects.

One thing that I have actively fought against is being pigeonholed as an artist. When I was starting out in my career, I noticed that curators were most interested in my works that explored topics related to my identity. They wanted works that explicitly showed my ‘Indian-ness’. Did they ask this of a white artist in studio visits? That offended me. Everything I think, do, or make is based and mediated through my cultural experience. It doesn’t matter the subject. It still gets filtered out through that experiential lens. But if you haven’t lived that experience you would not know the relevant questions to ask, which is why having a diversity of experience (in all its forms) is critical in power positions in the Arts. So early in my career, I consciously chose to explore a vast array of topics beyond my cultural identity. The connective threads and tissues are still there throughout all my bodies of work, but you gots to dig a little deeper to find them. Remember, the Art Market(ing) is different from Art.

PVT: But I wouldn’t say I “fight against” systems. Maybe it’s a semantic thing but ‘to fight’ implies an opposition manifested overtly. I am more subtle in my visual strategies within my work. Over the years I have explored a lot of difficult topics. My conceptual strategy has always been to act as a cultural mirror without overt judgment of stating that something is right or wrong, hoping that the “better angels” in each audience member would arrive at their own conclusions that hopefully would go to the side of reason, justice, and equality. It’s an implicit trust I have with the audience, that they will spend time and consider the subjects that I am exploring. It might be asking a lot of people who spend only a few seconds on a work of art. But I believe in the ‘slow-burn’… maybe that’s a mistake in an instant gratification society. But I respect and hold out hope for the audience to give a work of art the time it deserves.

Both the artworks you listed in your question are asking larger questions about culture while not being overt or didactic in their visual strategies. But if given enough time, I think all audiences would get to the point of asking “what the f*ck are we doing?!?” A Slow Burn.

ARW: A’ight, changing it up a lil’ bit. Here’s a potentially spicy one; why do you take pictures? I mean, there’s tons of different ways to make art and you’re no stranger to that idea—you’ve shown video, installation, drawings, and sounds to name a few different methods. What keeps you drawn to photography?

PVT: I came up during the Post-Modern period and Photography was the driving medium of that movement. How we use Post-Modern strategies to construct, interpret, and deconstruct the image is still relevant today, especially in a ‘Post-Truth’ digital world.

I love the image.

Photography, in my opinion, is the most democratic of all the artistic disciplines. Any individual can take a photograph. That does not necessarily mean any individual can take a good or sound photograph; but that all are able to participate. As with any artistic medium, the ability to effectively create a strong image comes with painstaking hard work and a commitment to the craft. There is a real beauty in knowing that we share the most accessible medium of all the Arts. It is this democratic nature that makes me fall in love with photography and the image every day.

© Prince Varughese Thomas, Body Count (209, 272 Pennies) & KIA (Charcoal Drawing on Wall), 2006-2019

ARW: I’m curious to know about how you maintain yourself when you’re in an artist block. Are there any people or things in your life that keep you inspired when you’re in a slump?

PVT: Up until COVID, I had never been in a slump because as I am wrapping up one body of work, I always have 2-3 ideas that are percolating in my head for the next project. And when the time comes, I wait for the right idea to pop out at the right time. So there are always ideas to explore. Now if I am stumped on what to make next in a particular body of work – I will make something else – something unrelated, until the next idea presents itself. In other words, I give myself permission to be ‘stupid’ and just make some shit for no reason… and it’s kinda fun to work on a piece and go “wow that just sucks!” I learn from the failures too! And that’s being human. An artist.

COVID really f*cked me up like many other people. Two days into the city shutdown my dearest friend (who was my ‘Best Woman’ at my wedding) died. Dealing with that at a time when the art community, friends, and family couldn’t get together to grieve her passing just sucked. That did a number on me for a while, where I just wasn’t motivated to get in the studio. But there is an expression that goes, “Artists get in the studio, when the pain of not making Art is greater than the pain of making Art.”

I guess for artist’s block I would say, trust that it will pass and don’t freak out about it. Go outside. Your mind is working on the problem without you.

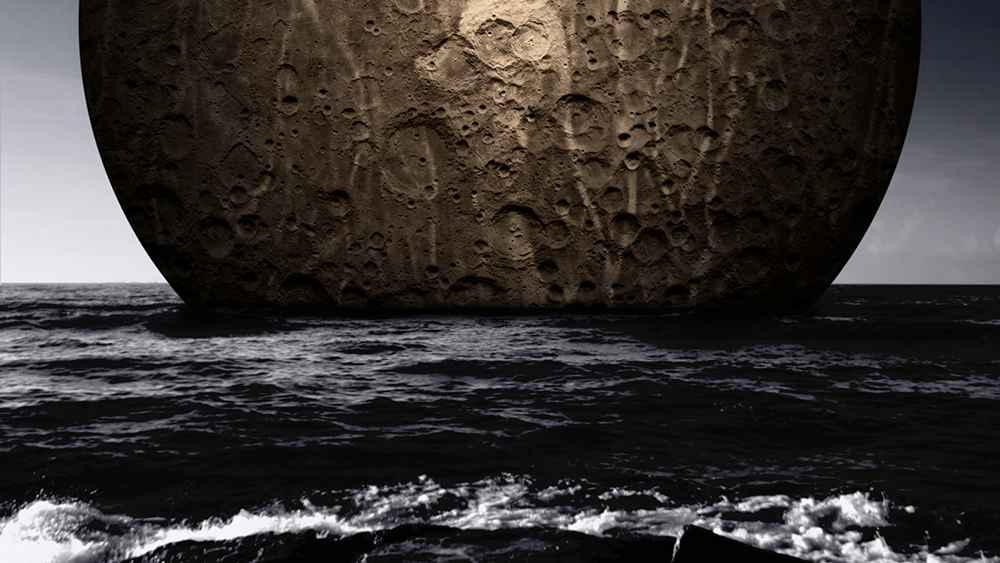

© Prince Varughese Thomas, Portrait of PewDiePie, from Masters of the Universe Series, Pigment Print, 2019

ARW: What is something (or some things) that you wish you knew when you were just starting out as an artist? Like, ya know, before you knew how grueling the art world is? [And if you don’t think it’s grueling, Prince, we may be living in different dimensions.]

PVT: I am a naïve realist. (I still want to believe in an overall fairness to the world that just doesn’t exist in my experience.)

The Art Market is different from Art. The market is a business but the artist is part of a community. “Start your own mafia.” An artist friend used to say this to me all the time. By that, he meant, for artists to keep in touch, stick together, and help each other out. I agree. Also, Work Hard. Get yourself and your work out into the public. Meet other artists that are like-minded. Work Hard. Invite others into your studio. Work Hard. Share your ideas and thoughts. Invite others to share with you. Work Hard. Don’t be plastic. People can read plasticity and it’s a big turn-off. But honesty and sincerity go a long way in my book and experience. And, WORK HARD. Don’t treat your art like a hobby but another full-time job.

I was walking down the streets of Toronto a few years ago and I read this on someone’s T-shirt, “Hustle beats Talent, when Talent don’t Hustle.” Bloody Brilliant! It’s very true in many fields including the Arts. I wish I could tell you that the art market is a meritocracy and that the best artists rise to the top of their profession. But it’s not. It’s not like in Sport where the best athletes can overcome any economic and social disadvantage to rise to the top of their field based on skill alone. The art market doesn’t work that way for the most part.

Being an immigrant, I was raised with that old-school work ethic of keeping one’s nose to the grindstone and trusting that good things will happen with hard work. I have maintained that work ethic throughout my professional life. I have been fortunate in my art career in that I have had wonderful people trusting and supporting me along the way. I can honestly say that everything I have ever achieved comes with the help of others. Obviously, hard work also plays a critical part in preparing oneself for situations where good things could happen to you; but I have never forgotten the help that I have received along the way. From my first job to my first exhibition, it has been, “Hey, there’s this guy named Prince that you should check out.”

And remember that rejection is only a negative, if you define success based on it. It is part of the process. To use a sports analogy, no baseball player bats a thousand. No basketball player hits all their shots. No golfer makes par on every hole. Failure is built into the process. Embrace it. I once got a rejection letter from a gallery that couldn’t even be bothered with sending me a standard form rejection letter. They simply mailed me a rejection on a yellow Post-It note. I loved it! It is now pinned on my memory wall in my studio. Don’t let rejection define you. Define your own success!

ARW: Thanks so much for sharing your wisdom with me, Prince. For someone who doesn’t go through a lot of artist blocks, you damn sure know what to do to help someone out of them. I’ll definitely be taking this advice to heart. ❤️

Now if I didn’t ask this, it just wouldn’t feel right; what are you working on right now?

PVT: I am in the middle of working on a new body of work for my show at Hooks-Epstein Galleries in Houston that is in conjunction with FotoFest 2022 which will open this September. The title of the show will be called America the Beautiful and explores through image and video my experience as a brown man in this culture. That’s a one sentence answer – the work is much more layered and complex than that, but I am not ready to write a statement about it just yet. I have included an image to give the readers a preview of my show.

ARW: Bonus question; how do you keep your beard so luxurious?

PVT: I’m easy. Soap.

Raised in the Southern states of Tennessee and Texas, André Ramos-Woodard (they/ them/ he/ him) is a contemporary artist who uses their work to emphasize the experiences of the underrepresented: celebrating the experience of marginalized peoples while accenting the repercussions of contemporary and historical discrimination. Working in a variety of media—including photography, text, and illustration—Ramos-Woodard creates collages that convey ideas of communal and personal identity, influenced by their direct experience with life as a queer African American. Focusing on Black liberation, queer justice, and the reality of mental health, Ramos-Woodard works to amplify repressed voices and bring power to the people.

Ramos-Woodard received their BFA from Lamar University in Beaumont, Texas, and their MFA at The University of New Mexico in Albuquerque, New Mexico.

Follow André Ramos-Woodard on Instagram: @andreduane

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

Luther Price: New Utopia and Light Fracture Presented by VSW PressApril 7th, 2024

-

Artists of Türkiye: Sirkhane DarkroomMarch 26th, 2024

-

European Week: Sayuri IchidaMarch 8th, 2024

-

European Week: Steffen DiemerMarch 6th, 2024

-

Rebecca Sexton Larson: The Reluctant CaregiverFebruary 26th, 2024