Benjamin Dimmitt: An Unflinching Look: Elegy for Wetlands

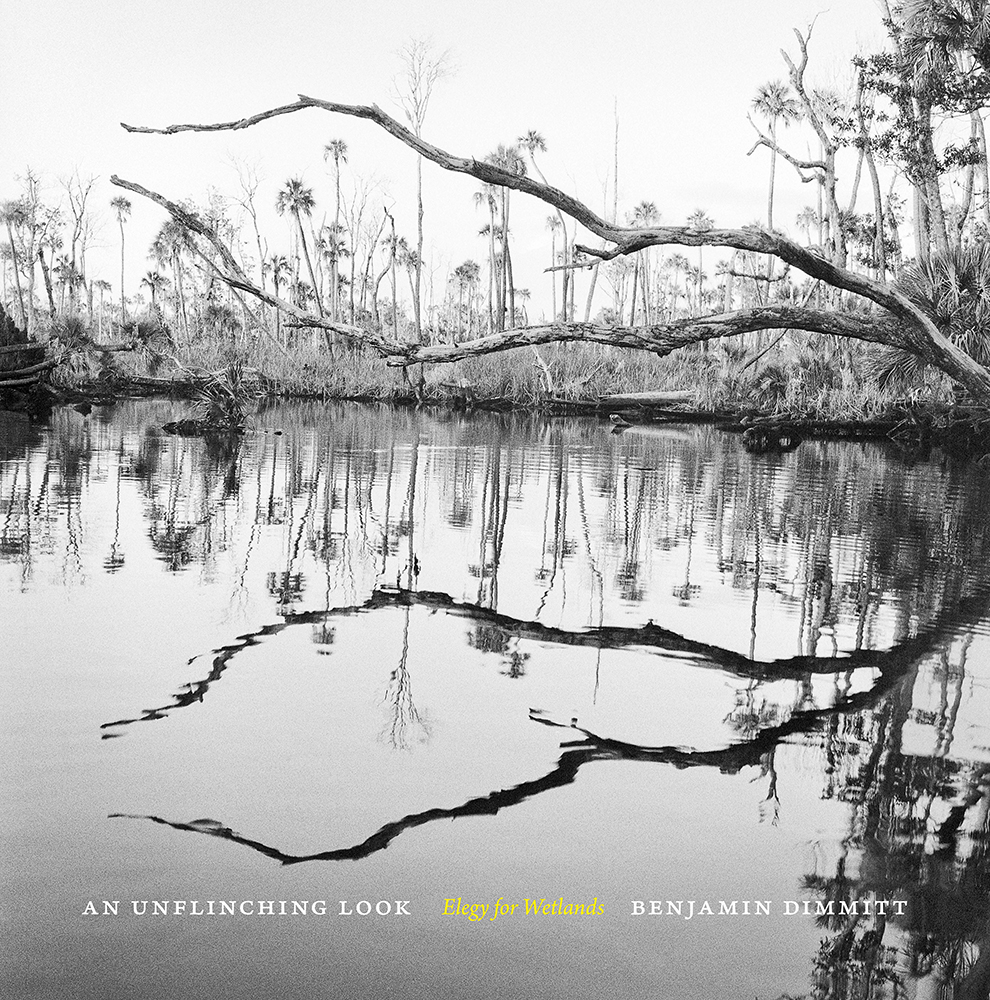

©Benjamin DImmitt, Book Cover for An Unflinching Look: Elegy for Wetlands, Published by the University of Georgia Press.

“An Unflinching Look is a powerful expression of ecological grief, bearing witness to loss and devastation within our lifetimes. His powerful documentation of extraordinary climate change is not only important but also a necessary telling of the world in crisis.”- Aline Smithson

Sometimes I have the great pleasure of following a years-long project and see it come to fruition in book form. That is the case of Benjamin Dimmitt‘s new monograph, An Unflinching Look: Elegy for Wetlands a project that I have featured on Lenscratch a number of times. Published by the University of Georgia Press. this a focus that it vitally important in our witnessing of climate change.

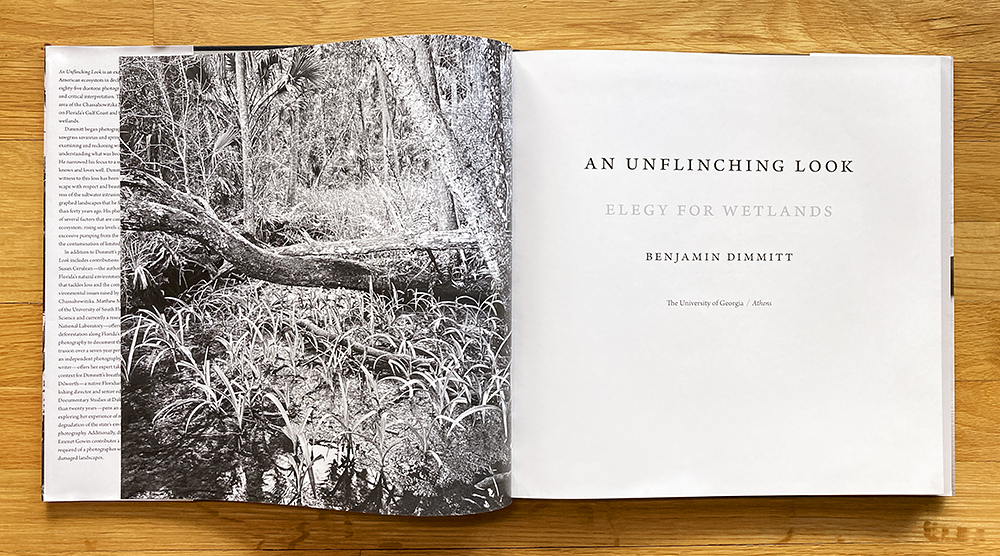

An Unflinching Look is an examination of a unique North American ecosystem in decline, investigated through eighty-five duotone photographs, scientific analysis, and critical interpretation. The project’s focus is the area of the Chassahowitzka National Wildlife Refuge on Florida’s Gulf Coast and the history and fate of its wetlands. Dimmitt began photographing in the salt-damaged sawgrass savannas and spring creeks there as a way of examining and reckoning with the ecosystem loss and of understanding what was becoming of his native Florida. He narrowed his focus to a small, remote area that he knows well and loves. Dimmitt’s intention in bearing witness to this loss has been to portray the ruined landscape with respect, nuance, and beauty. To document the progress of the saltwater intrusion, Dimmitt has rephotographed landscapes that he first photographed more than forty years ago. His photographs reveal the impact of several factors that are causing the loss of an entire ecosystem: rising sea levels caused by global warming, excessive pumping from the underground aquifer, and the contamination of limited natural resources.

Special Contributions from: Susan Cerulean, author of several books about Florida’s natural environment. Matthew McCarthy, a graduate of the University of South Florida College of Marine Science and currently a research scientist at Oak Ridge National Laboratory. Alison Nördstrom, independent photography curator, scholar, and writer. Alexa Dilworth, native Floridian and former publishing director and senior editor at the Center for Documentary Studies at Duke University. Emmet Gowin, distinguished landscape photographer and professor at Princeton University.

Books can be purchased at: University of Georgia Press, Malaprop’s Bookstore, and Tombolo Books

An interview the artist follows.

©Benjamin DImmitt, Title Page from An Unflinching Look: Elegy for Wetlands, Published by the University of Georgia

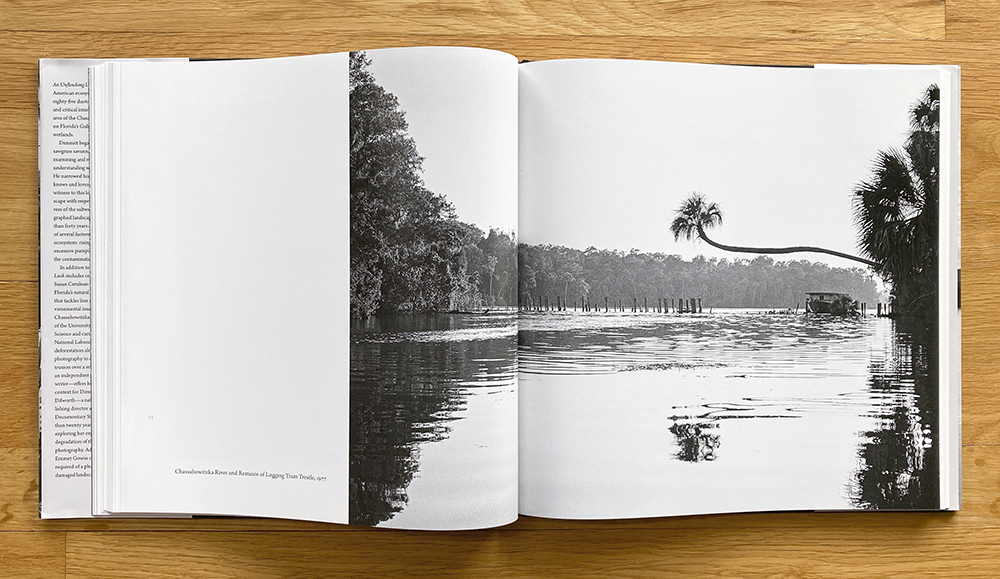

©Benjamin DImmitt, Chassahowitzka River, 1977, Spread from An Unflinching Look: Elegy for Wetlands, Published by the University of Georgia Press.

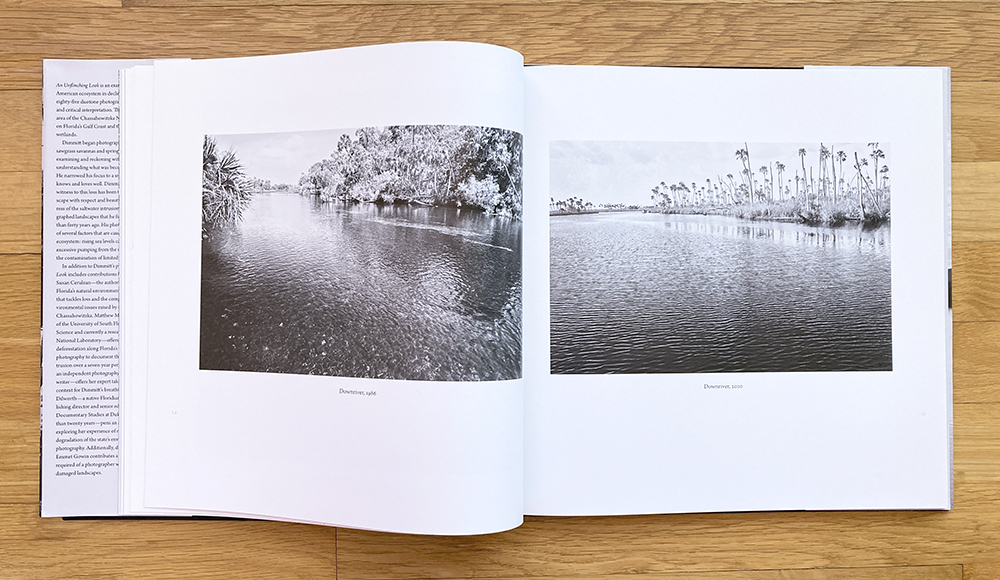

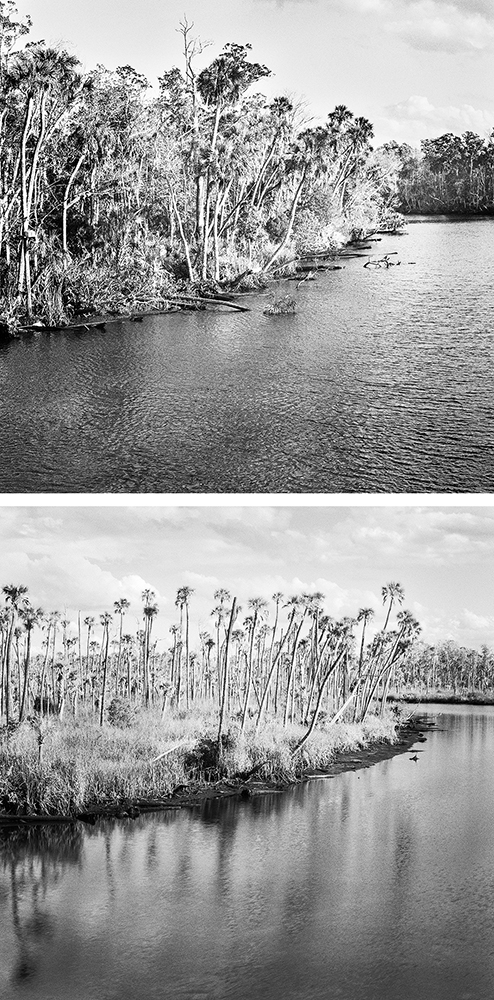

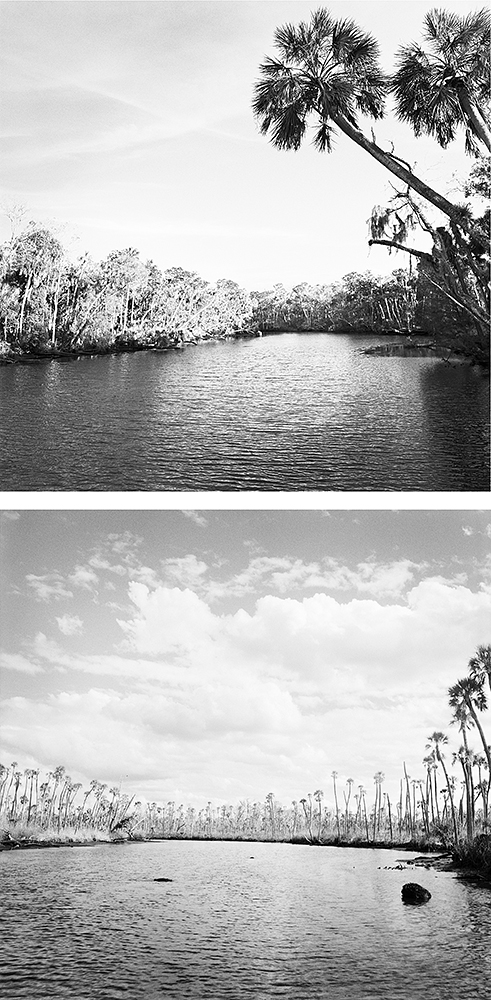

©Benjamin DImmitt, Downriver 1986, 2020, Spread from An Unflinching Look: Elegy for Wetlands, Published by the University of Georgia Press.

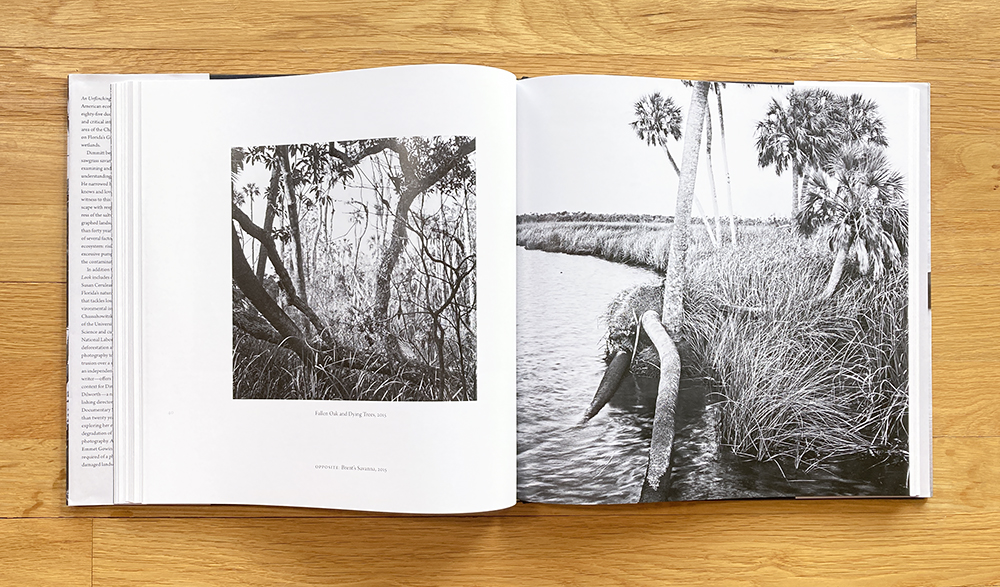

©Benjamin DImmitt, Fallen Oak and Dying Trees, 2015_Brent’s Savanna, 2015, Spread from An Unflinching Look: Elegy for Wetlands, Published by the University of Georgia

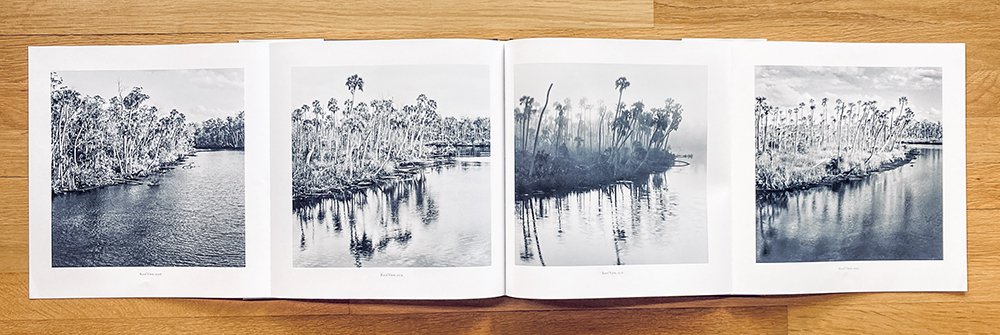

©Benjamin DImmitt, Roof View 2006, 2014, 2016, 2022, Spread from An Unflinching Look: Elegy for Wetlands, Published by the University of Georgia

The Chassahowitzka National Wildlife Refuge is a very fragile, spring-fed estuary on Florida’s Gulf Coast, 70 miles north of Tampa. I was overwhelmed by its lush, primeval beauty on my first visit there in 1977 and have photographed there extensively since 2004. The dense palm hammocks and hardwood forests were festooned with ferns and orchids and the spring fed creeks were a clear azure. There are other similar estuaries nearby but the Chassahowitzka River and the surrounding wetlands are protected as part of the federal National Wildlife Refuge system and the river itself is designated as an Outstanding Florida Water.

Saltwater began creeping up into the spring creeks around 2010. Rising sea levels due to global warming are the primary cause. Additionally, Florida’s unique underground fresh water aquifer, which supplies the state’s drinking water, has been mismanaged, polluted and inadequately regulated for decades. Excessive pumping for developers, power companies, mining, agricultural interests and bottled water companies has diminished the underground aquifer, allowing saltwater to take its place. This drawdown has also taken fresh water away from the springs that feed the Chassahowitzka and other nearby rivers. As the fresh water flow in the estuaries decreased, saltwater advanced upstream and took its place, leaving behind ghost forests. What had been verdant, semi-tropical forest is now predominantly an open plain of grasses relieved by palms and dying hardwood trees. Sabal palms are the most salt tolerant trees in this ecosystem and are the last to expire. This deforestation is a widespread phenomenon, occurring all along the Big Bend section of Florida’s west coast.

In 2014, I began photographing in the salt-damaged sawgrass savannas and spring creeks there as a way of reckoning with the ecosystem loss and of understanding what has become of my native Florida. I have narrowed my focus to a small, remote area that I love and know well. My intention in bearing witness to this loss has been to portray the ruined landscape with respect and beauty. The inundation of this estuary serves as a bellwether for low-lying coasts around the world. – Benjamin Dimmitt

©Benjamin DImmitt, Enchanted Bend, 2004, from An Unflinching Look: Elegy for Wetlands, Published by the University of Georgia

Tell us about your growing up and what brought you to photography.

My mother was an artist. Our home was full of paintings and drawings, both abstract and realistic. When I was a child, I once asked her what a painting of hers was “of” and she replied that pictures don’t have to be of anything, they just are.

My mother used photographs to paint from and she gave me cameras, many cameras over the years. I photographed family and friends but mostly I photographed my surroundings, the wetlands and the woods near our home in Florida. When she gave me a 35 mm camera for my 16th birthday, I learned how to use it and became more committed to photography. We had many helpful discussions and critiques where I, then a college student, began to value her opinions and our artistic similarities and differences.

©Benjamin DImmitt, Blue Run 2, 1988, from An Unflinching Look: Elegy for Wetlands, Published by the University of Georgia

Congratulations on the book, how did that come about? Where can we order it?

Thank-you!

Quite a few years ago, a photography dealer and a photography gallery owner, both of whom I knew and both from NYC where I lived at the time, told me emphatically that my climate change project should be a book. They both said that they couldn’t sell prints of this work.

So, I started by contacting a publisher in Atlanta but that didn’t work out. I learned very important lessons from that experience, though.

In 2020, a friend suggested the University of Georgia Press and gave me an introduction to the director of the press. It has been a terrific working relationship! I was given free rein with image choice and image sequence and they were supportive of my suggestions, like the two four-image gatefold spreads. Their gifted designer created an elegant and photography-forward design. I’m thrilled!

It can be ordered through the University of Georgia Press, Tombolo Books and Malaprop’s Bookstore.

©Benjamin DImmitt, Bridge Tree, 2004, from An Unflinching Look: Elegy for Wetlands, Published by the University of Georgia

How did this long-term project begin?

In 2004, I began a project photographing the wetlands, palm hammocks and low-lying forests of my native Florida in a process of exploring and interpreting the unique and fragile beauty there. The remaining wilderness in Florida has been put at risk by unfettered growth, rising seas and irresponsible resource management. One of my favorite places to photograph for this project was the Chassahowitzka Wildlife Refuge. In 2014, I discovered that global warming and rising seas were pushing saltwater up into the spring-fed estuaries. This, along with over pumping from the aquifer, was creating ghost forests all along the Big Bend coast of Florida. I committed then to documenting this environmental devastation in a new project titled An Unflinching Look. The photographs in the project and in the book span forty-five years.

©Benjamin DImmitt, Horizontal Palms & Creek, 2004 from An Unflinching Look: Elegy for Wetlands, Published by the University of Georgia

Can you speak to the pairing of images that starkly reveal the degradation of these landscapes?

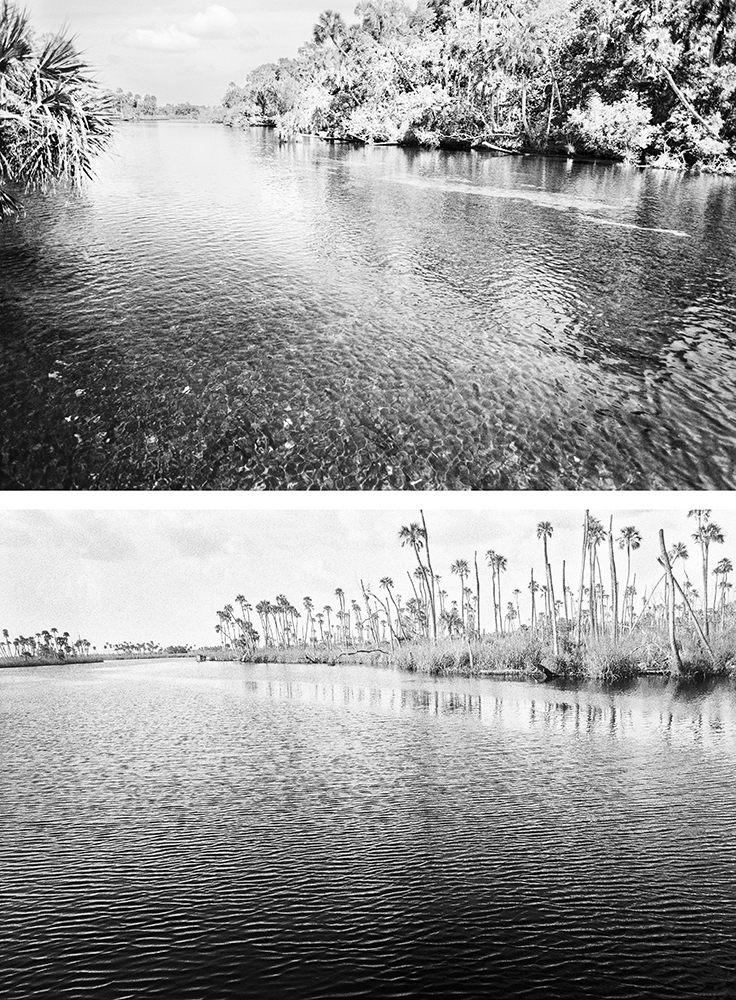

Before a 2016 exhibit at my former gallery in Tampa, the owner asked me if I had old photographs of these ghost forest scenes that would provide some context. I began making these re-photographic diptychs then and felt that they were a very effective mode of describing the progress of the ruin at Chassahowitzka. The follow-up photographs were difficult to make because my old film cameras don’t have GPS to guide me to the exact location of my archival photographs. Most often, I used the trees in the earlier photograph to help position myself for the follow-up photograph. Unfortunately, the deforestation caused by rising sea levels has killed off many of these locator trees. When presented together, the two photographs become one grim fact.

©Benjamin DImmitt, Downriver 1986, 2020 from An Unflinching Look: Elegy for Wetlands, Published by the University of Georgia

What has compelled you to return again and again to the same subject matter?

These wetlands and forests were a beautiful and distinctive part of my native landscape. Initially, I wanted to show the ruin and provide evidence that global warming had reached this unique and vulnerable little place. I was fully committed to the subject and to the project; I made more than 25 trips down to the swamp between 2014 and 2022. As the years passed and I continued my photography, I realized that the project was also a farewell and a passionate record of loss.

Having a book contract also provided motivation!

©Benjamin DImmitt, Lower Crawford Creek 1988, 2014 from An Unflinching Look: Elegy for Wetlands, Published by the University of Georgia

It is surely emotional to return to a place over the years and watch its decline and transformation.

Yes, it is emotional! I’m not really sure how I faced the slow environmental destruction year after year. Emmet Gowin opens his beautiful 2002 book, Changing The Earth, with the following quote which addresses this subject. He very generously contributed this piece to my book. I can’t say it any better.

“ In a landscape photograph, both the mind and heart need to find their proper place. Before the landscape we look for an invitation to stand without premeditation. It is always, in some sense, our home. At times, we may also look for an architecture of light and a poetry of atmosphere which welcomes the eye into a landscape of natural process. It may also be the map–the evidence of the thing itself: may it also, always be a vision of the double world–the world of appearances and the invisible world all at once. Even when the landscape is greatly disfigured or brutalized, it is always deeply animated from within. When one really sees an awesome, vast, and terrible place, we tremble at the feelings we experience as our sense of wholeness is reorganized by what we see. The heart seems to withdraw and the body seems always to diminish. At such a moment, our feelings reach for an understanding.

This is the gift of a landscape photograph, that the heart finds a place to stand.”

©Benjamin DImmitt, Roof View 2006, 2022 from An Unflinching Look: Elegy for Wetlands, Published by the University of Georgia

What does the future hold for these parts of Florida? What kind of research informs your own witnessing of climate change?

The Gulf of Mexico will continue to move up into the brackish creeks along the Big Bend coast of Florida. As the aquifer is pumped for fresh water for golf courses and new communities, salt water will continue to move upstream and into the aquifer. Flooding will increase as storms worsen. What were once crystal clear spring-fed creeks are already brown, silty and becoming covered with mats of toxic algae.

I did a great deal of research for the book. The press insisted on that.

I’ve also been collaborating for years with a research scientist whose doctoral thesis deals with saltwater intrusion along the Gulf coast. His study is excerpted in the book.

©Benjamin DImmitt, View Upstream 2004, 2022 from An Unflinching Look: Elegy for Wetlands, Published by the University of Georgia

Is this a lifelong project or does having a book bring it to a conclusion?

It’s easy to understand how this book may bring the project to an end. Already underway is a project photographing mangrove communities that I’ve been working on for years. I’d love to dig in deeper on that once all my book responsibilities conclude. We’ll see…

©Benjamin DImmitt, Roof View, 2016 from An Unflinching Look: Elegy for Wetlands, Published by the University of Georgia

©Benjamin DImmitt, Palms in Creek, 2017 from An Unflinching Look: Elegy for Wetlands, Published by the University of Georgia

©Benjamin DImmitt, Blue Run Shore, 2014 from An Unflinching Look: Elegy for Wetlands, Published by the University of Georgia

Benjamin Dimmitt is the son of a native Floridian and an artist from New York. He was born and raised on the Gulf Coast of Florida. When he was given a camera as a boy, the wetlands and woods near his home were his first subjects. He studied photography at Eckerd College, Santa Fe Photographic Workshops and the International Center of Photography. Additionally, he studied printmaking at Santa Reparata Graphic Arts Centre in Florence, Italy and City; Guild Arts School in London, England.

Dimmitt held an adjunct professor position at International Center of Photography from 2001-2013. He taught at Southeast Museum of Photography in 2018 and at Penland School of Craft in 2022. He was a finalist in Photolucida’s Critical Mass Top 200 in 2014, 2017, 2018 and 2019 and in New Orleans Photo Alliance’s Clarence John Laughlin Award in 2014 and 2015. His photographs have been exhibited in museums, galleries and festivals internationally and are held in multiple major museums and private collections.

Follow on Instagram: @benjamin_dimmitt_photography

Follow University of Georgia Press on Instagram: @ugapress

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

Luther Price: New Utopia and Light Fracture Presented by VSW PressApril 7th, 2024

-

From Here to the Horizon: Photographs in Honor of Barry LopezApril 3rd, 2024

-

Shinichiro Nagasawa: The Bonin IslandersApril 2nd, 2024

-

Kristine Nyborg: Learning to Speak BearApril 1st, 2024