THE CENTER AWARDS: SOCIALLY ENGAGED AWARD: SOFIE HECHT

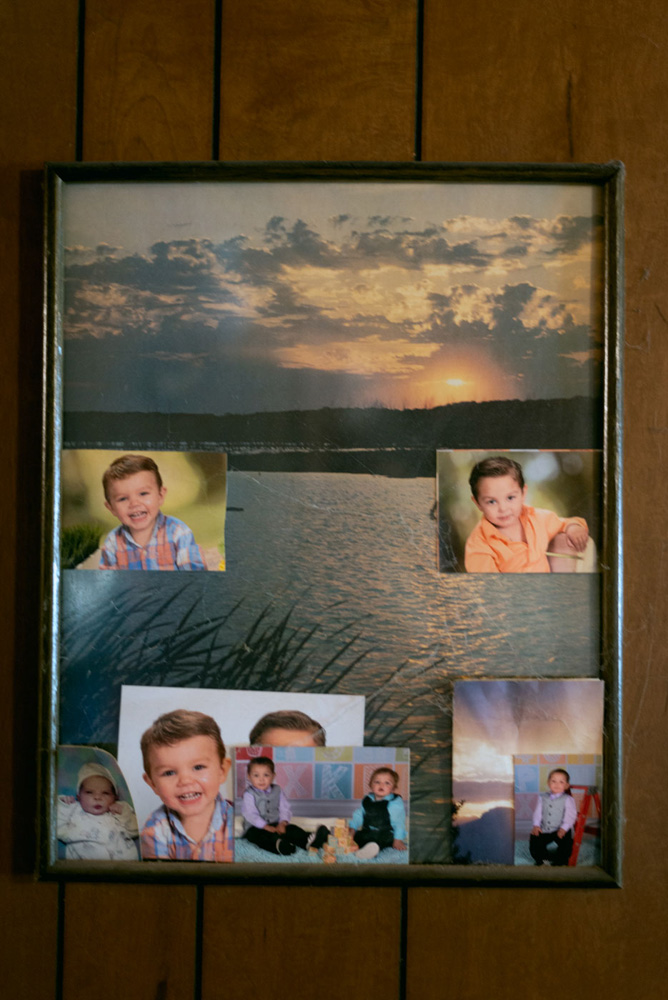

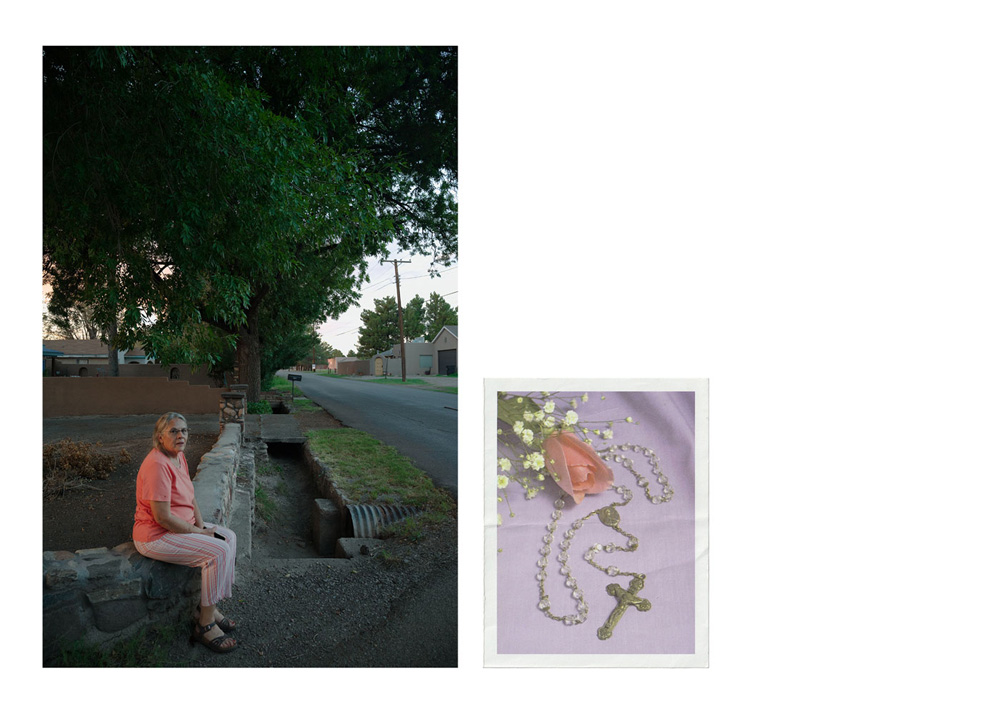

© Sofie Hecht, Family photographs hang on the wall in Andrea Carrillo’s mother’s home on Sierra Blanca Rd in Tularosa, NM. Andrea and many of her friends and family grew up on Sierra Blanca Rd. and now have cancer that they attribute to the radiation exposure caused by the Trinity atomic bomb test. Andrea’s sister died of cancer a few years ago.

The CENTER Awards recognize outstanding images, singular or part of a series, in three categories: Personal, Social, and Environmental. All submissions will become part of the CENTER archive serving as an ongoing mission-driven fine art and documentary imagery resource.

The CENTER Awards recognize outstanding images, singular or part of a series, in three categories: Personal, Social, and Environmental. All submissions will become part of the CENTER archive serving as an ongoing mission-driven fine art and documentary imagery resource.

Congratulations to Sofie Hecht on being selected for CENTER’S Social Award recognizing her project, Downwind. The Social Awards recognize work engaged in social issues. All projects exploring social topics or themes were eligible. The Award includes Professional Development Seminars, Complimentary participation and presentation at Review Santa Fe, Project Publication in Lenscratch, and inclusion in the CENTER Winners Gallery & Archive.

JUROR: Noelle Flores Théard, Senior Digital Photo Editor, The New Yorker, shares her thoughts on the selection:

Socially engaged projects come in many forms and a wide range of topic areas as evidenced by the high numbers of excellent submissions for the Socially Engaged Award. I chose the project Downwind as the winner of this award due to the photographer’s passionate and wholehearted approach in documenting communities living within 50 miles of the detonation of the first atomic bomb. Through photography, archival research, and oral histories, the project makes visible the continued effects of radiation on community members.

Two other projects that greatly impacted me were Meeting Hall Maine, which took a serialized approach to photographing these historic spaces where civic discourse thrived, and another project, An Impossibly Normal Life, which used vernacular and constructed photography to imagine what it might have been like for the artist’s queer uncle, born in 1930, to live an open, loved, and supported life.

Pressing social justice issues such as oil drilling in Black neighborhoods of Los Angeles, the devastating toll of Lyme disease on young people, and the challenges of plastic recycling in Bangladesh made me appreciate more traditional photojournalistic approaches. I was also moved to see two projects exploring the devastated local news industry. Intensely personal projects deepened my understanding of photographers’ experiences, such as the loss of disappeared loved ones in Colombia, and several powerful first-person accounts of severe illness.

There are so many ways to approach meaningful photography projects – being on the jury for this year’s Socially Engaged Award opened my mind to the range of possibilities that photographers can explore in creating their work. I hope to see many of these projects continue to grow in the coming years, and I would encourage all those who applied to keep producing and sharing their work in order to inspire social change.

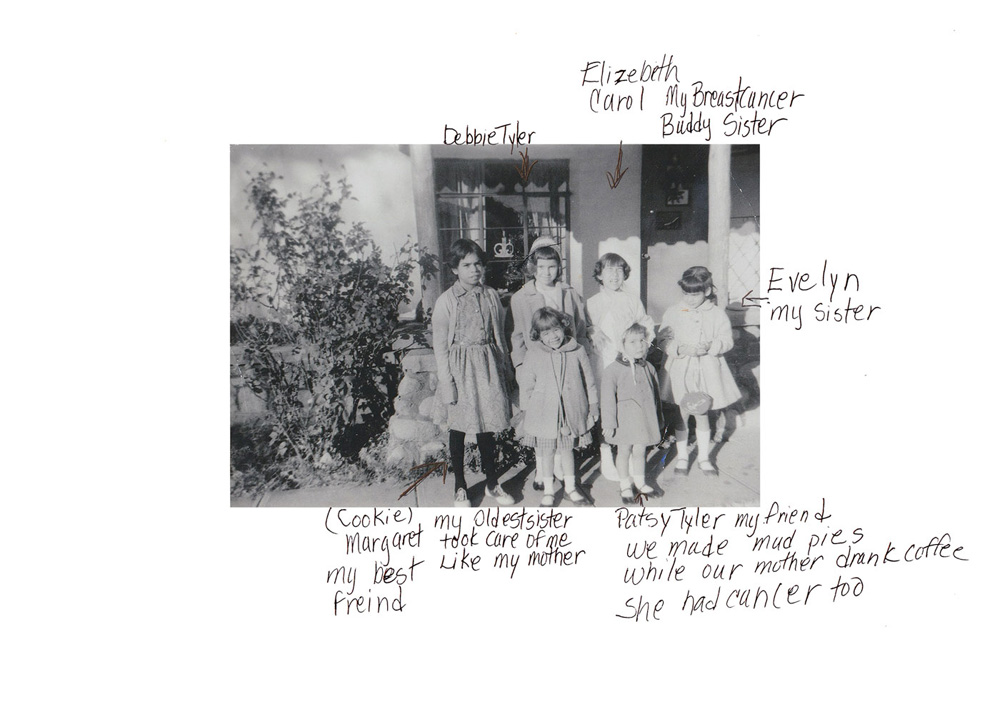

© Sofie Hecht, Reaching for?, Lucy Benevidez Garwood and her daughter Doris around 1955. Doris’s family grew up in Tularosa, NM, just 55 miles from the Trinity site. 5 generations of their family have had cancer, from Lucy’s grandmother Evarista Baca to Doris’s daughter Katherine and great-niece Adriana.

Sofie Hecht is a documentary photographer born in Brooklyn, New York, and based in Albuquerque, New Mexico. Her work focuses on queer community, particularly collaborative portraiture, documenting drag performances, and returning home to photograph her own biological family. She graduated from Tufts University in 2018 with a degree in International Literary and Visual Studies (ILVS) and Spanish. She moved to Albuquerque, New Mexico, in 2019 where she began working for the non-profit youth group home Casa Q that supports queer youth without a safe home. She then became a paralegal focused on civil rights lawsuits against prison and jails in support of folks who were incarcerated. She enrolled in the International Center of Photography’s Documentary and Visual Practice online program for their 2023 school year where she worked on a long-term project documenting the effects of the nuclear industrial complex on New Mexican families, particularly those in the 50-mile radiation zone from the Trinity site. Sofie also continues to work on a long-term documentary and portrait project The Queer Family Photobook about how queer people make alternative family units in Albuquerque. She is now a Graduate Assistant at the University of New Mexico’s Communication and Journalism department.

Follow Sofie Hecht on Instagram: @sofiehext

Downwind

Detonated in Southern New Mexico on July 16, 1945, Trinity’s residual fallout traveled as far as Canada, Mexico, and 46 U.S. states. Half a million people lived within the primary 150 square-mile radiation zone of the world’s first atomic bomb. 78 years later, the legacy of Trinity lives on in astounding rates of cancer and illness in these communities. Downwind uses archival materiality—from family photographs, letters, documents, interviews—to represent the deterioration of land and bodies exposed to radiation. It tells these stories through portraits, oral histories, and a decaying family archive. As the archive itself shows signs of aging within an environment exposed to radiation, so too do the Downwinders.

Downwind supplements the archive with new materials to breathe life into this decay.

In the past year, I have focused on the communities in the closest 50-mile radius from Trinity. I have interviewed over 20 different families that suffer from illnesses that they believe are connected to Trinity’s radiation fallout (radiogenic cancers, thyroid issues, fertility problems, vision impairments). I have spoken to 4th generation cancer survivors who have lost children, granddaughters, parents and neighbors to cancer. Many of these people are farmers whose primary food source comes from their own or neighbor’s gardens which are still contaminated. The Downwinders commonly say “We don’t ask if we’re going to get cancer, we ask when.”

The Downwinders are currently fighting to be included in the Radiation Exposure Compensation Act before the bill sunsets in June 2024. As the urgency of receiving financial support for an entire community’s suffering only increases, Downwind is a project of preservation amidst the precarious landscape of nuclear contamination.

This work aims to embolden collective visions of future and challenge imposed Time. Downwind follows the lead of family matriarchs who don’t rest until everything they believe sacred is well-maintained. With the act of documentation is a belief that these stories deserve to live into the future. – Sofie Hecht

© Sofie Hecht, What lies ahead for her? Josephine Duran and her niece Doris Walters sit in Josehine’s house on Set. 22, 2023. Doris’s mom Lucy (Josephine’s sister) was born in the very room they sit in 92 years ago. Josephine, Doris, and many other family members who grew up in Tularosa developed cancer that they attribute to their proximity to the fallout of the 1945 atomic bomb test.

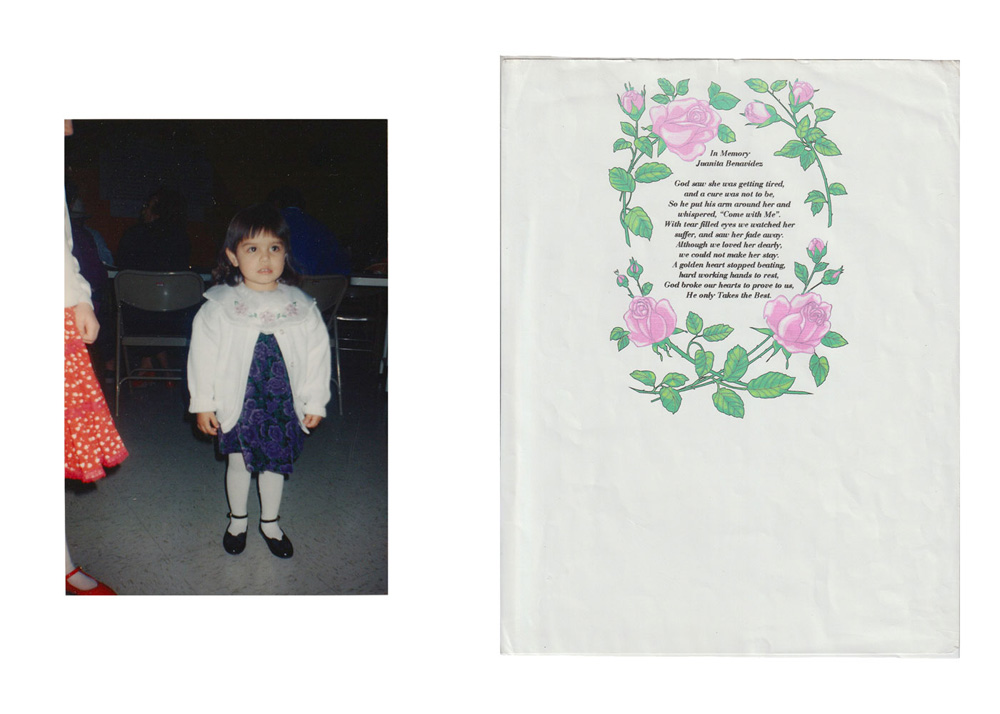

© Sofie Hecht, Pink Flowers, Adriana (left) died of leukemia at the age of 22 years old. She is the granddaughter of Josephine Duran and great-granddaughter of Juanita Benevidez, who died in 1994 of breast cancer. A pamphlet from Juanita’s memorial is paired with the image of Adriana when she was young. Adriana and Juanita both grew up in Tularosa until their deaths and there are 5 generations of women who experienced cancer in their family.

© Sofie Hecht, Nan, Nan Ramzel in her home in Socorro on September 3, 2023. Nan lives only 30 miles away from the Trinity site and her father witnessed the bomb explosion. Nan has heart problems that she attributes to the radiation exposure.

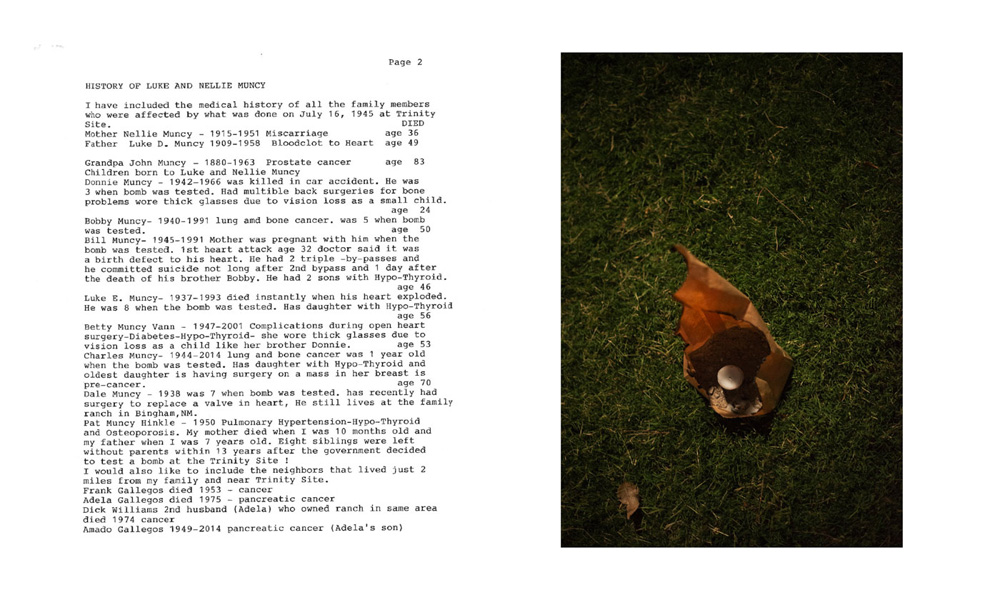

© Sofie Hecht, Dipytch, Pat Muncy Hinkle’s family history is written down to catalog the members of her family who died of cancer after growing up the Bingham, NM, area just 13 miles from the Trinity site. On the right is a burned luminaria from a candlelight vigil held on July 16, 2023, to commemorate the 78th anniversary of the Trinity test and its victims.

© Sofie Hecht, Richard loved music, The grave where Lousia Lopez’s husband Richard Lopez, and their son are buried on their land. Photographed on September 3, 2023.

© Sofie Hecht, Scars, Doris Walters shows me her breast on September 23, 2023. Doris had a mastectomy a few years ago after a battle with breast cancer. Her and many of her family members have had cancer that they attribute to living in such close proximity to the Trinity atomic bomb test in 1945.

© Sofie Hecht, The green house, Outside of the green home in Bingham, NM, along highway 380 on September 4, 2023. Pat Muncy Hinkle’s family grew up in this home just 13 miles away from the explosion site of the world’s first atomic bomb.

© Sofie Hecht, Untitled, Photographs in Ernest Baca’s home in Tularosa on August 8, 2023. Ernest has two sisters who died of cancer and is related to Doris Walters, who has a long family history of cancer.

© Sofie Hecht, Paul, Paul Pino in his home in Sandia ark on August 7, 2023. Paul is a member of the Tularosa Basin Downwinder’s Consortium. Paul grew up in Carrizozo, a town 30 miles away from where the Trinity test was detonated. Paul’s family has a history of various cancers that they believe were a result of living in Carrizozo close to where the bomb went off.

© Sofie Hecht, Lousia Lopez stands on her ranch in San Antonio, NM, on Aril 19, 2023. Louis’as husband Richard died of cancer 3 years ago and his family has been plagued by cancer for generations. Louisa and her husband joined the activist group the Tularosa Basin Downwinder’s Consortium (TBDC) after noticing high mortality rates in their community.

© Sofie Hecht, Adriana’s last birthday, A photograph from Adriana Montoya’s last birthday before she died of leukemia months later.

© Sofie Hecht, Fading, a photograph of Pat Muncy Hinkle’s mother Nellie Muncy (far left) and her friends in the Bingham, NM, area just 13 miles from the Trinity site.

© Sofie Hecht, Untitled, A tin, hand-colored portrait of Lucy Benevidez-Garwood. Lucy is 92 years old and heard the Trinity bomb when it was detonated just 50 miles away from her home. Now, many of her family members have cancer.

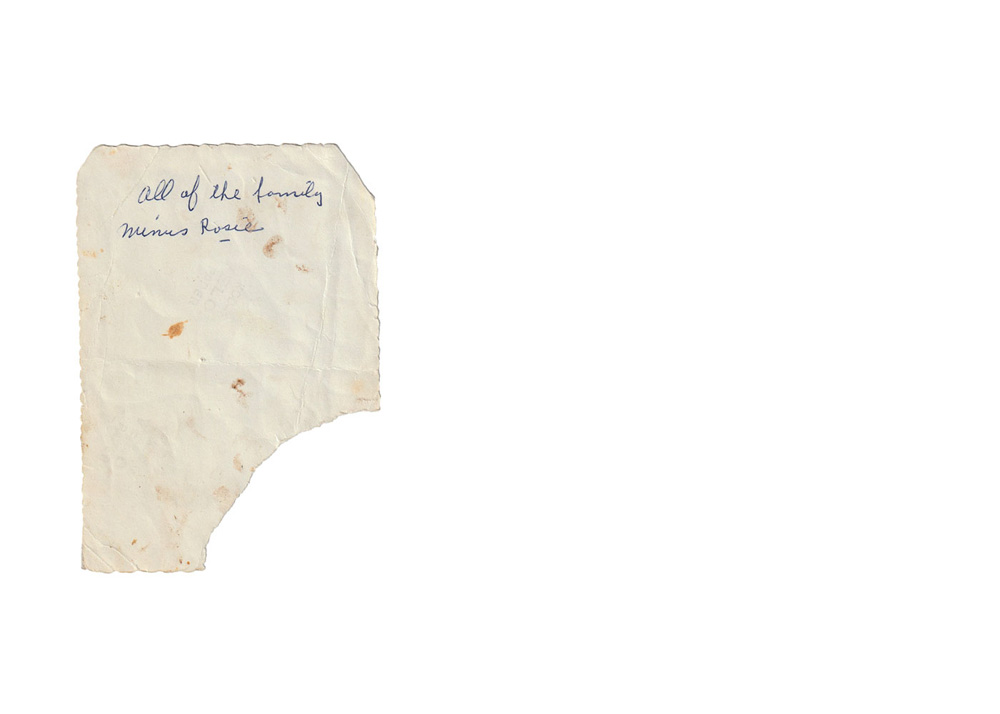

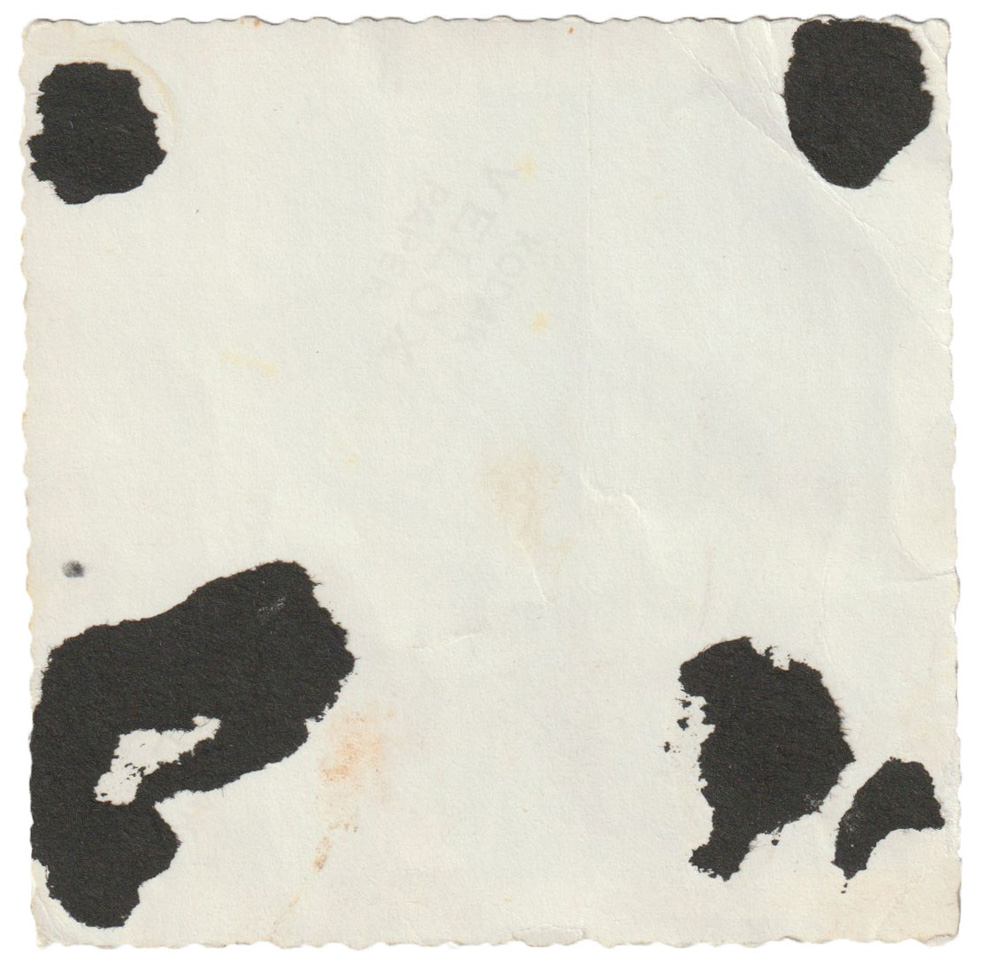

© Sofie Hecht, Preservation, The back of a photograph in Doris Walters’s family archive that reads, “all of the family minus Rosie”.

© Sofie Hecht, Acequias, Left: Doris Walters sits outside the home her grandfather built and in which her aunt Josephine now lives. Doris grew up playing in the water in the ditch outside the home with her friends. Now, her and all her friends have developed cancer that they believe is connected to their proximity to the Trinity atomic bomb test of 1945. Right: A pamphlet from the memorial of one of Doris’s family members.

© Sofie Hecht, Untitled, Andrea Carrillo walks around her neighborhood in Tularosa, NM, pointing out all the people in the community who have been affected by cancer. Andrea and many of her friends and family grew up on Sierra Blanca Rd. and now have cancer that they attribute to the radiation exposure caused by the Trinity atomic bomb test. Andrea’s sister died of cancer a few years ago.

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

Shane Hallinan: The 2025 Salon Jane Award WinnerFebruary 12th, 2026

-

Greg Constantine: 7 Doors: An American GulagJanuary 17th, 2026

-

Yorgos Efthymiadis: The James and Audrey Foster Prize 2025 WinnerJanuary 2nd, 2026

-

Arnold Newman Prize: C. Rose Smith: Scenes of Self: Redressing PatriarchyNovember 24th, 2025

-

Celebrating 20 Years of Critical Mass: Cathy Cone (2023) and Takeisha Jefferson (2024)October 1st, 2025

![In the early morning of Sunday, September 15, 1963, four members of the United Klans of AmericaÑThomas Edwin Blanton Jr.,Herman Frank Cash, Robert Edward Chambliss, and Bobby Frank CherryÑplanted a minimum of 15 sticks of dynamite with a time delay under the steps of the 16th Street Baptist Church in Birmingham, Alabama, close to the basement.

At approximately 10:22 a.m., an anonymous man phoned the 16th Street Baptist Church. The call was answered by the acting Sunday School secretary: a 14-year-old girl named Carolyn Maull. To Maull, the anonymous caller simply said the words, "Three minutes", before terminating the call. Less than one minute later, the bomb exploded as five children were present within the basement assembly, changing into their choir robes in preparation for a sermon entitled "A Love That Forgives". According to one survivor, the explosion shook the entire building and propelled the girls' bodies through the air "like rag dolls".

The explosion blew a hole measuring seven feet in diameter in the church's rear wall, and a crater five feet wide and two feet deep in the ladies' basement lounge, destroying the rear steps to the church and blowing one passing motorist out of his car. Several other cars parked near the site of the blast were destroyed, and windows of properties located more than two blocks from the church were also damaged. All but one of the church's stained-glass windows were destroyed in the explosion. The sole stained-glass window largely undamaged in the explosion depicted Christ leading a group of young children.

Hundreds of individuals, some of them lightly wounded, converged on the church to search the debris for survivors as police erected barricades around the church and several outraged men scuffled with police. An estimated 2,000 black people, many of them hysterical, converged on the scene in the hours following the explosion as the church's pastor, the Reverend John Cross Jr., attempted to placate the crowd by loudly reciting the 23rd Psalm through a bullhorn. One individual who converged on the scene to help search for survivors, Charles Vann, later recollected that he had observed a solitary white man whom he recognized as Robert Edward Chambliss (a known member of the Ku Klux Klan) standing alone and motionless at a barricade. According to Vann's later testimony, Chambliss was standing "looking down toward the church, like a firebug watching his fire".

Four girls, Addie Mae Collins (age 14, born April 18, 1949), Carol Denise McNair (age 11, born November 17, 1951), Carole Robertson (age 14, born April 24, 1949), and Cynthia Wesley (age 14, born April 30, 1949), were killed in the attack. The explosion was so intense that one of the girls' bodies was decapitated and so badly mutilated in the explosion that her body could only be identified through her clothing and a ring, whereas another victim had been killed by a piece of mortar embedded in her skull. The then-pastor of the church, the Reverend John Cross, would recollect in 2001 that the girls' bodies were found "stacked on top of each other, clung together". All four girls were pronounced dead on arrival at the Hillman Emergency Clinic.

More than 20 additional people were injured in the explosion, one of whom was Addie Mae's younger sister, 12-year-old Sarah Collins, who had 21 pieces of glass embedded in her face and was blinded in one eye. In her later recollections of the bombing, Collins would recall that in the moments immediately before the explosion, she had observed her sister, Addie, tying her dress sash.[33] Another sister of Addie Mae Collins, 16-year-old Junie Collins, would later recall that shortly before the explosion, she had been sitting in the basement of the church reading the Bible and had observed Addie Mae Collins tying the dress sash of Carol Denise McNair before she had herself returned upstairs to the ground floor of the church.](http://lenscratch.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/02/001-16th-Street-Baptist-Church-Easter-v2-14x14-150x150.jpg)