lydia see: Let no one say we were not here

This week, we will be exploring projects inspired by intimacy and memory. Today, we’ll be looking at work by lydia see.

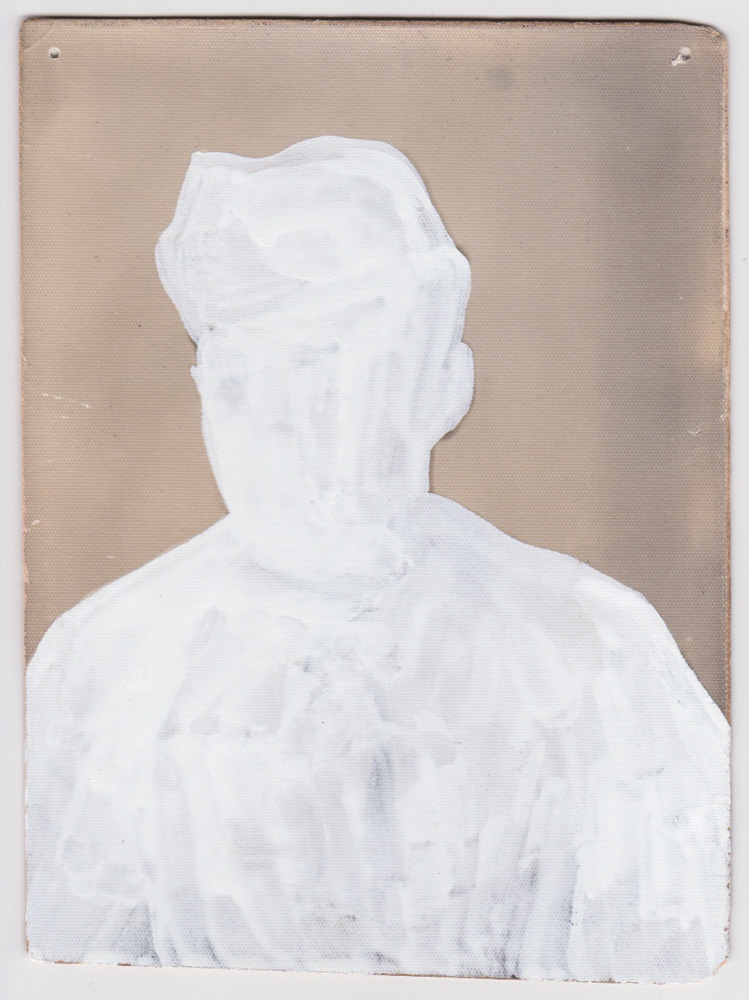

I met lydia see in February 2020 a few weeks before the world shut down. We shared an elevator in Chicago at the College Art Association, and one of us mentioned that we were in graduate school. Surprisingly, we were both attending programs in North Carolina – Western Carolina University and Eastern Carolina University. From there, we made plans to curate an exhibition between our schools which unfortunately went awry with the pandemic. We have since kept in touch over the years. lydia is an artist who always inspires me. Her work uncovers the fundamental powers images hold; to transport, to understand, to explore, to desire, to remember. lydia hones in on small details innate in humanity to conceptually focus on the role images play in our lives. With simple changes such as painting over the figures in an image with gouache, the image meanings shift. lydia is able to balance these impressions in their images.

lydia see (she/they/y’all) is a multidisciplinary practitioner, educator, and curator of art + archives who is a firm believer in the transformative power of art for collective liberation. Northeastern by birth, Appalachian by choice, and currently residing on the ancestral lands of the Tohono O’odham Nation and the Pascua Yaqui Tribe (Tucson, AZ), lydia is a serial collaborator who works through themes of duration, belonging, and displacement across photography, fiber, sculpture, performance, and social/public practice.

Follow lydia on Instagram at: @lydiasee.studio

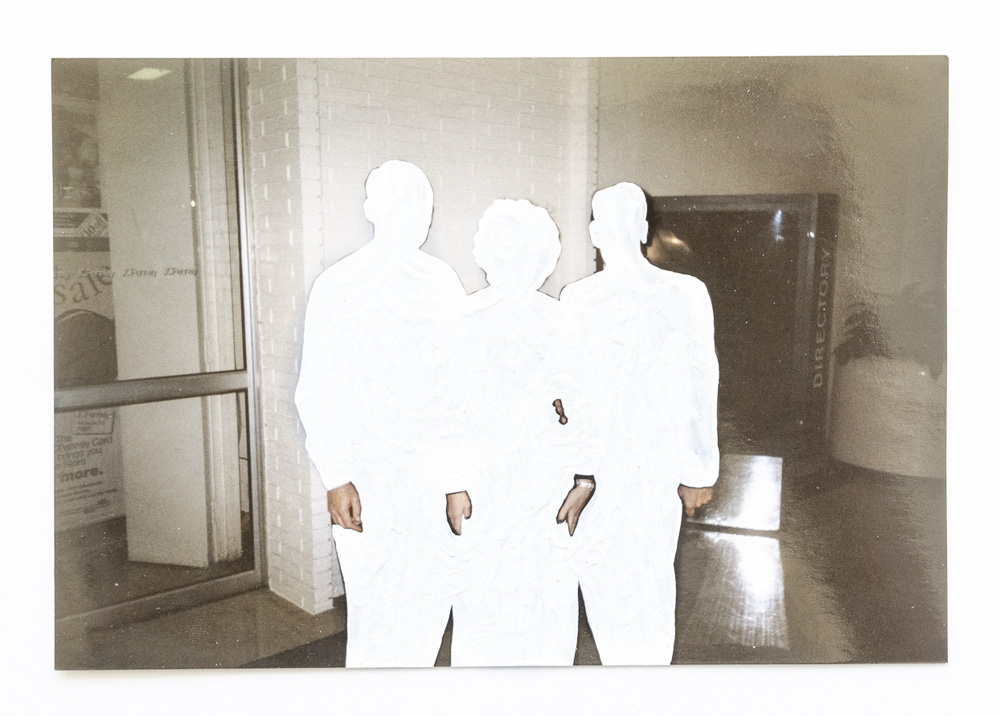

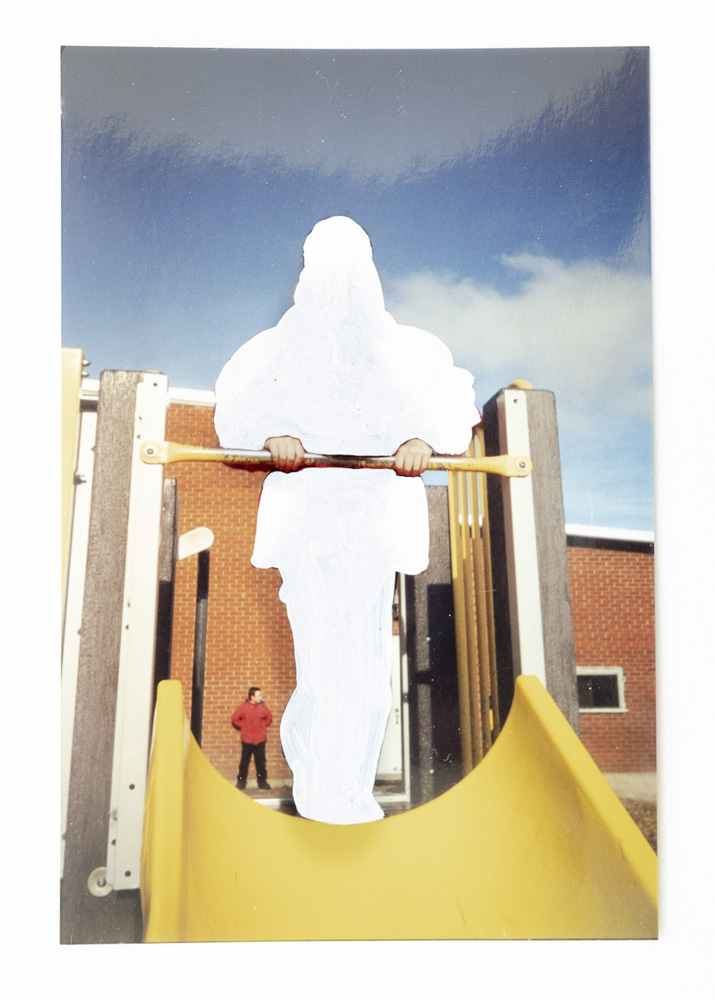

The works in this ongoing series are accumulations of slow, iterative gestures. Whether I’m thinking about representation and performance of gender (felt cute, might delete later), belonging within familial structures (I don’t know what to do with my hands), or big negotiations of grief (Let no one say we were not here), I use a painting over process with white gouache to examine my own internalized misogyny, proximity to the power afforded by white supremacy, and relationship with community.

Epiphany Knedler: How did your project come about?

lydia see: Altering photographs using various gestures and media, such as embroidering onto or weaving prints, or painting parts of images over with gouache, is central to my practice. Sometimes the process pokes fun at the act of making or posing for a photograph itself, as in I don’t know what to do with my hands or felt cute, might delete later (see images), and sometimes that veneer of silliness can feel a little on the nose or satirical. Photography is slippery in that way—in its ability to hold both humor and heartbreak.

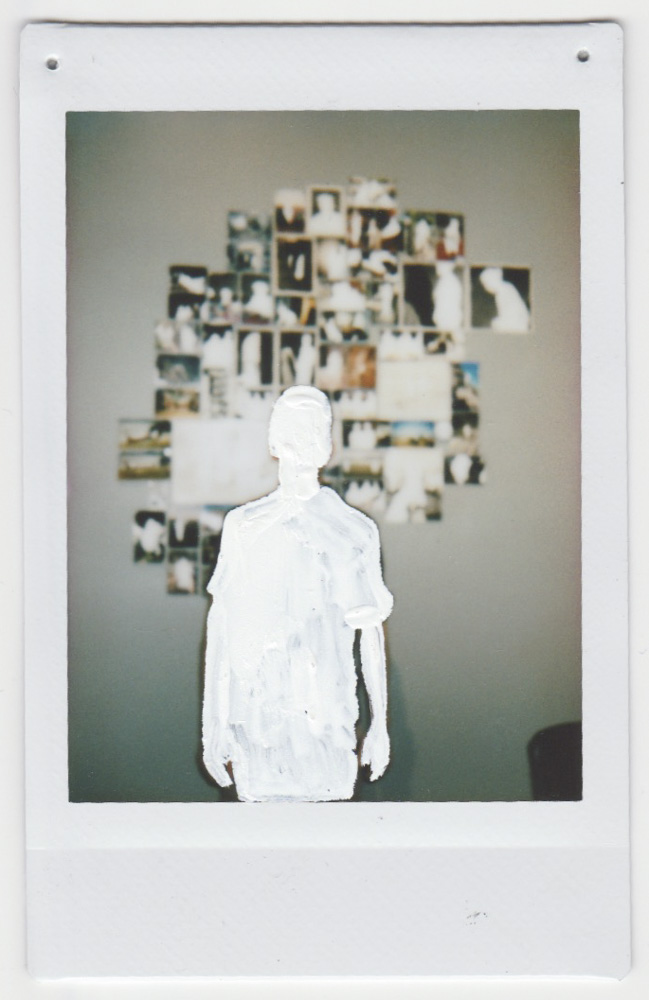

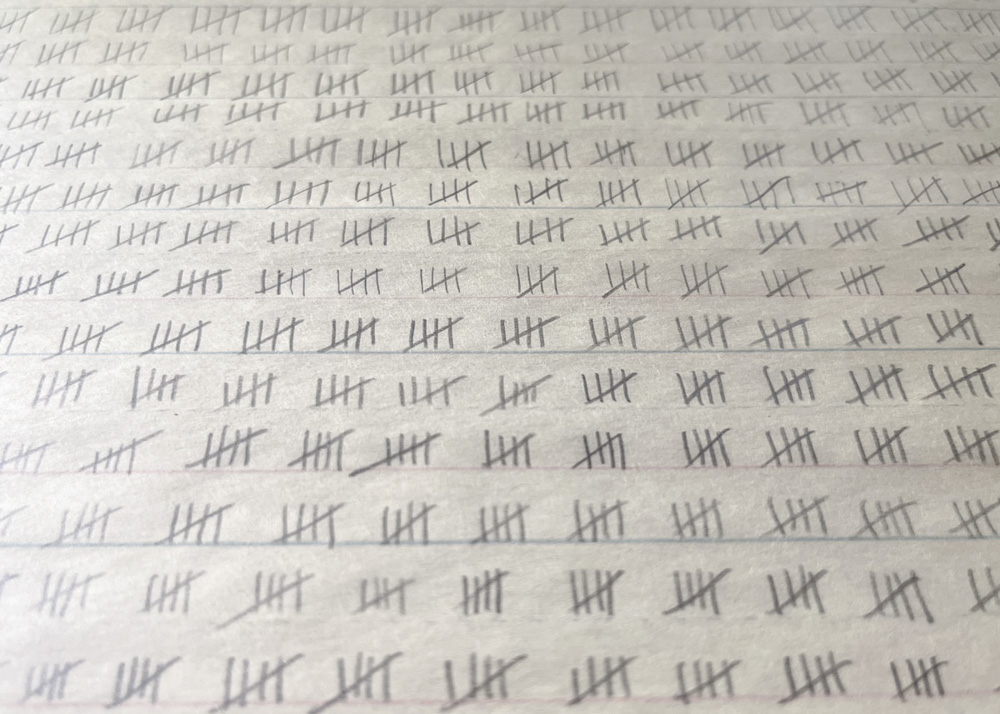

In 2020, I shifted my gouache painting-over process into durational performance in an attempt to visually quantify and process the loss of life each day from the COVID-19 virus by painting over humans from my own family photos, images given to me, pictures and yearbooks acquired through library book sales, estate sales, and various other sources. It started with the death of my uncle from COVID, and I painted every day for months, and then years. I kept a tally, and never came close to the daily death toll. In 2023 installed the work and performed the painting-over in the Tucson Museum of Art for the Arizona Biennial, inviting the public to donate images to the work in memorial of their loved ones to create a shared family album of collective loss.

Let no one say we were not here is part durational performative practice, part socially engaged collaboration, and part coping mechanism for grief. It is impossible to conceptualize loss of life at this scale, and statistically each of us has lost someone we know to COVID, a single member of an incalculable statistic. A human being, a life. But it’s about displacement, too. Redaction. Archival silence. Painting over these images—whiting them out to erase them—must also be an act of reflection on the construct of whiteness itself. History has been recorded by survivors and oppressors, and COVID-19 has disproportionately impacted systemically oppressed populations. How will this traumatic loss of life be represented in its historicization?

©lydia see, Let no one say we were not here, 2020-ongoing. Visitors were invited to donate images and share stories of loved ones who died from COVID-19 while live painting over donated and accumulated images occurred in the museum gallery.

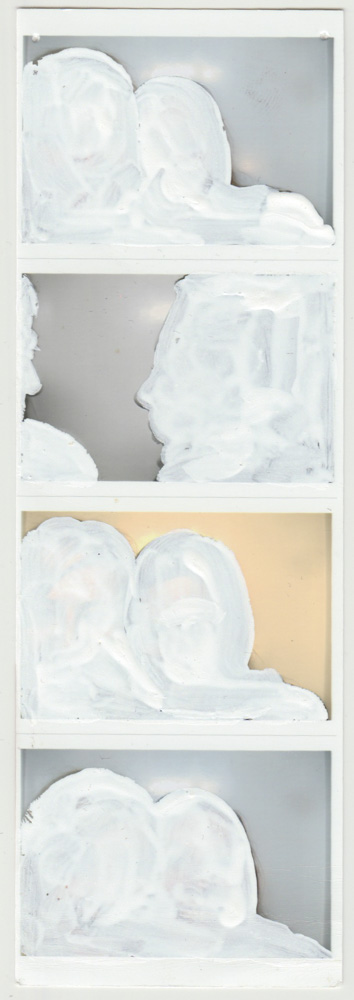

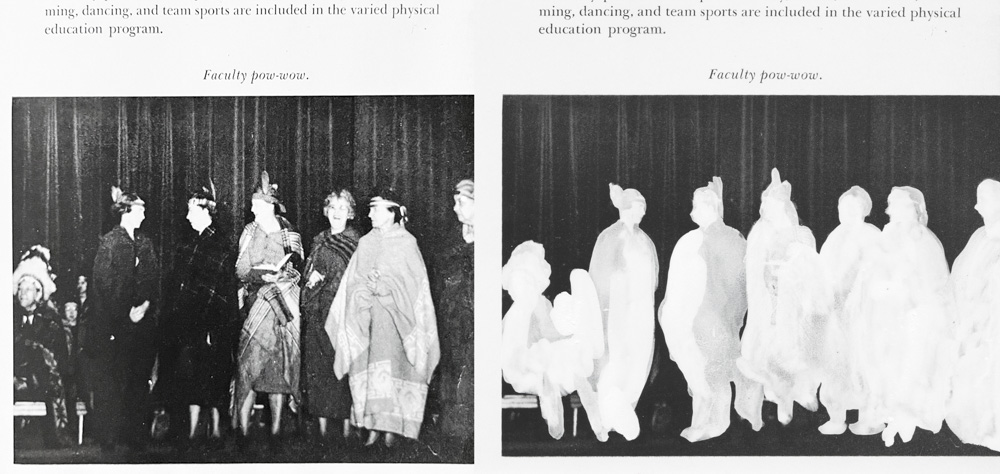

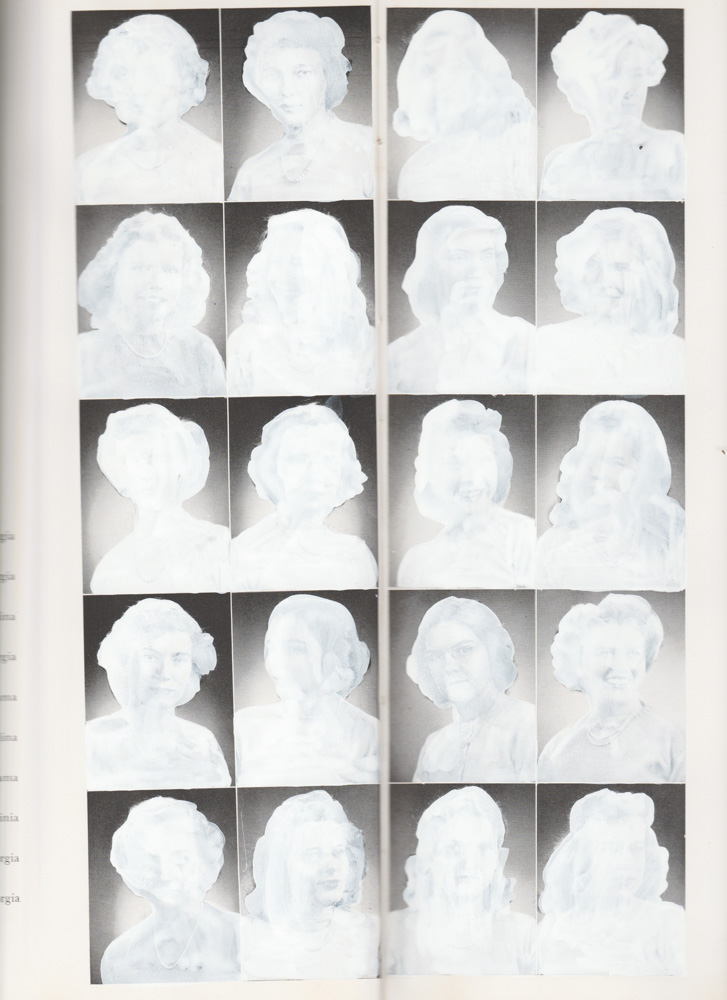

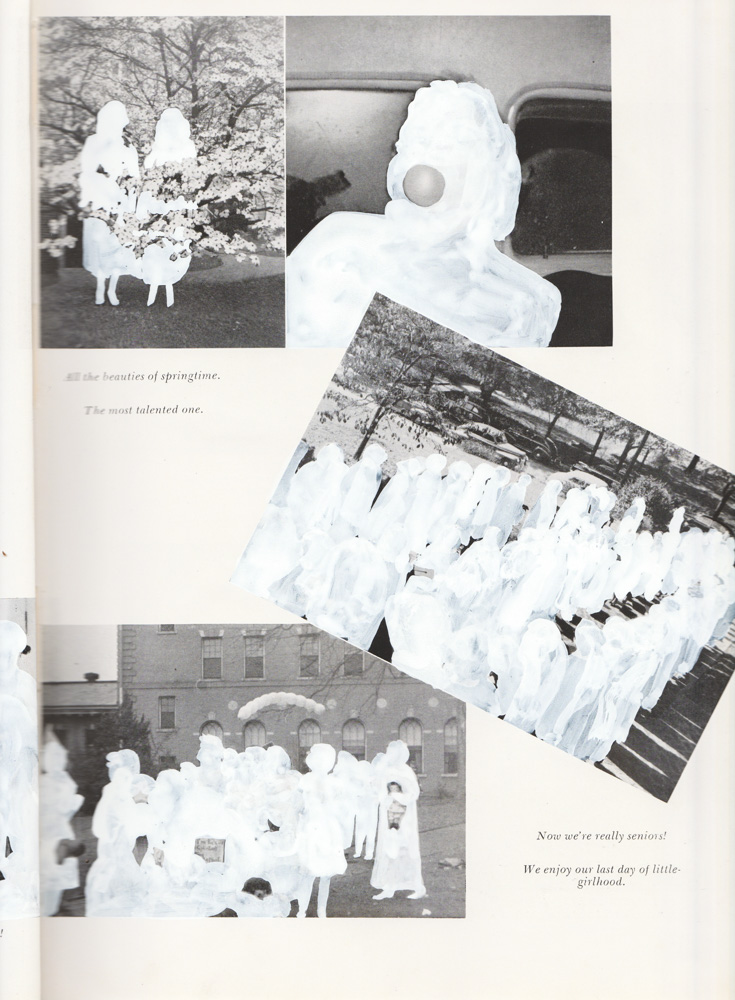

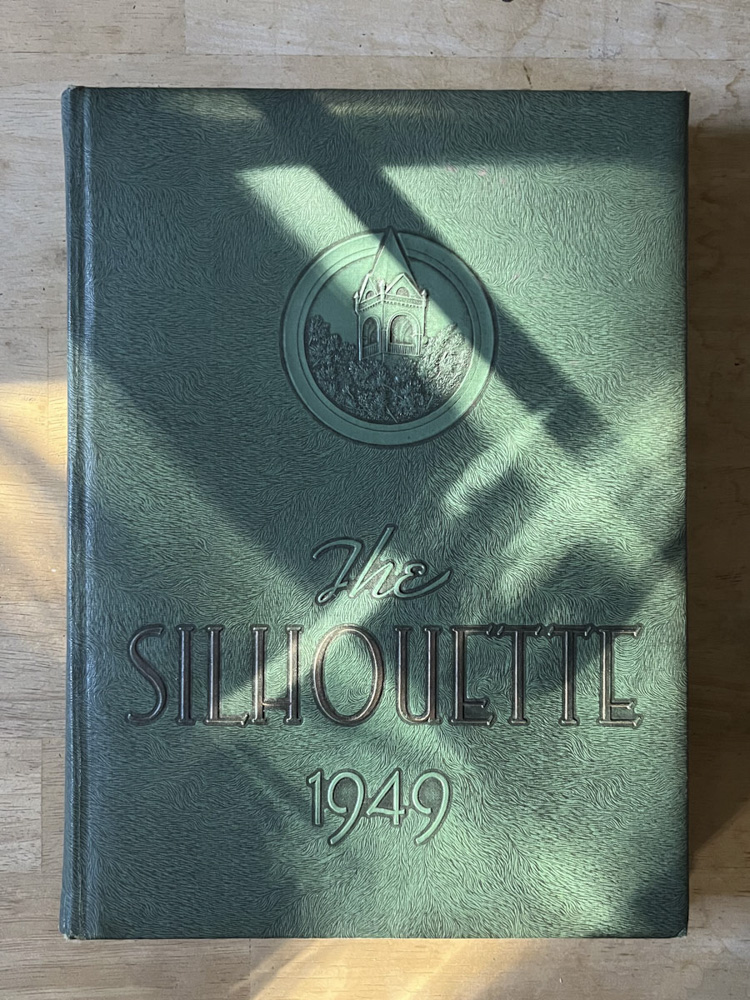

In 2023 shortly after deinstalling at the Biennial, I began a second iteration of this work to help me process my grief and rage at the swift and merciless slaughter of Palestinians which has been occurring for 262 days (and 76 years) at the time of this publishing. I selected a 1949 yearbook from Agnes Scott, a private women’s college in Decatur, Georgia, from my collection of cast-off yearbooks. While Agnes Scott now reports that around 67% of their students self-identify as minoritized (by race or LGBTQIA2S+ status), the college did not integrate until 1965, so the 1949 yearbook appears as comprised of entirely white-passing and extremely traditionally feminine students. As a white, queer, anti-zoinist Ashkenazi Jew who is constantly grappling with my own gender, by looking at these women in the eyes—women who were enrolled in a PWI in the Jim Crow South at the time of the “end” of the Nakba as the 1948 Palestine war drew to a close—while whitewashing them, I am confronted with my own relationship to the white supremacy that creates the conditions within which such atrocities as genocide flourish.

©lydia see, Let no one say we were not here, for Palestine, 2023-ongoing. durational performance, 1949 Agnes Scott yearbook, gouache, cursive practice paper, pencil.

©lydia see, Let no one say we were not here, for Palestine, 2023-ongoing. durational performance, 1949 Agnes Scott yearbook, gouache, cursive practice paper, pencil. Yearbook cover, tally of the dead on cursive practice newsprint paper, painted over pages from the yearbook.

EK: What relationship does memory or intimacy play within your practice, and does photography become a way to navigate these complex topics?

ls: Photography is absolutely an agent of complexity, and I have spent years renegotiating my feelings about how it shows up in different forms in my practice. Sometimes it feels like I no longer make photographs, which of course isn’t true!, but my work currently leans more towards alteration, appropriation, and recontextualization.

When I began heavily working with family and archival photographs, I became fascinated by the murky spaces between the vernacular photograph and the family photograph, a photograph as proof of something, as a moment frozen in time separated from its context, as wholly unreliable and capable of harm, as evidence. There are so many incredible practitioners whose use of vernacular or archival images has majorly impacted me—Carrie Mae Weems’ From Here I Saw What Happened and I Cried, Wendy Red Star’s 1880 Crow Peace Delegation, Ariella Aisha Azoulay’s Civil Contract and Potential History, and Tacita Dean’s Floh to name a few—and I think they all hang out in that murky space really beautifully.

It’s likely that when we remember something, we are remembering the last time we remembered it rather than the original memory itself, adding in additional information and context based on the last recollection itself and our current perspective, because memory is not stationary. So if we look at images—in the family album, in the news, of a birthday party, family vacation, or monumental event—we replace the comprehensive experience of the event into its constituent snapshots, and fill in the rest. I think about photography’s influence on the “filling in the rest” a lot.

EK: Is there a specific image that is your favorite or particularly meaningful to this series?

ls: While Let no one say we were not here was on view, I had an “inbox” where visitors could submit images to the ongoing series. The submitted images from strangers have become the most meaningful to me because of the trust that was given to me by strangers to memorialize their loved ones. (image details – files labeled “donation”)

©lydia see, felt cute might delete later, 2019. Screenshots of mirror selfies made by women and non-binary people in my Instagram feed, gouache painted over except for the hands.

EK: Can you tell us about your artistic practice?

ls: I work across photography, fiber, sculpture, performance, and social/public practice, and I’m interested in the often unseen aspects of artistic labor. I’m research-driven, and most of my work starts with an unanswerable question that I process through making. Thematically, a lot of it has to do with belonging, displacement, and making duration visible in the work.

©lydia see, Let no one say we were not here, 2020-ongoing. Visitors were invited to donate images and share stories of loved ones who died from COVID-19 while live painting over donated and accumulated images occurred in the museum gallery.

I also work as a curator, an arts writer, and an educator, and I see all of these various forms of creative labor as inexorably linked to my practice. I love gassing other artists up—especially emerging artists—by writing, and curating exhibitions, and producing interventions in spaces like libraries and archives that amplify non-dominant narratives and voices. I get super pumped about intentional display/delivery systems, conceptually rich exhibition design choices, and accessible professional practice support for artists.

At the end of the day I really struggle to maintain balance as a practitioner, an institutional cultural laborer, and a human who just wants to make stuff without having to consider where it’s going to go or who will consume it while constantly grappling with impostor syndrome. I think recently I’ve just been making slow, iterative work (I also weave and embroider) in order to have difficult conversations with myself through repetition, and that’s ok for me for the time being.

Epiphany Knedler is an interdisciplinary artist + educator exploring the ways we engage with history. She graduated from the University of South Dakota with a BFA in Studio Art and a BA in Political Science and completed her MFA in Studio Art at East Carolina University. She is based in Aberdeen, South Dakota, serving as a Lecturer of Art and the co-curator for the art collective Midwest Nice Art. Her work has been exhibited in the New York Times, Vermont Center for Photography, Lenscratch, Dek Unu Arts, and awarded through the Lucie Foundation, F-Stop Magazine, and Photolucida Critical Mass.

Follow Epiphany Knedler on Instagram: @epiphanysk

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

Time Travelers: Photographs from the Gayle Greenhill Collection at MOMADecember 28th, 2025

-

Photography Educator: Juan OrrantiaDecember 19th, 2025

-

Bill Armstrong: All A Blur: Photographs from the Infinity SeriesNovember 17th, 2025

-

Rebecca Sexton Larson: The PorchApril 28th, 2025

-

Matthew Cronin: DwellingApril 9th, 2025