Photographers on Photographers: Paul Fauller in conversation with Matthew Leifheit

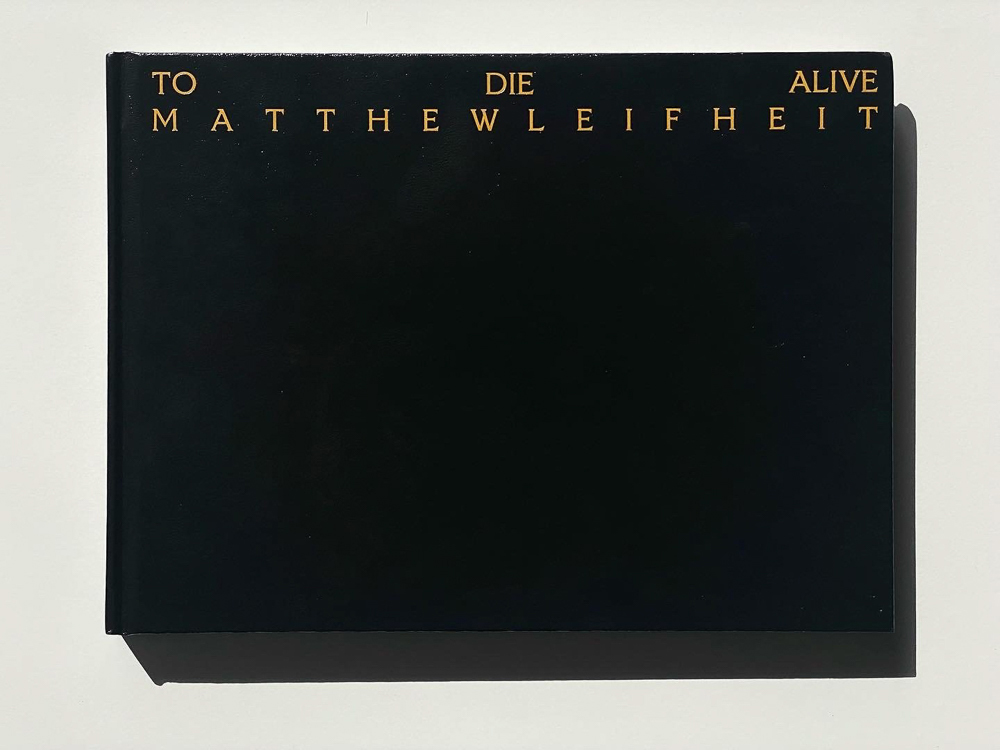

I first met Matthew Leifheit after one of his artist talks at MassArt my freshman year of art school, and I found myself entranced—he is the founder of MATTE magazine, MATTE institute: a free photography school, a professor at several universities, and is most importantly an incredible photographer. He dedicates himself to platforming emerging photographers and establishing community within the photography world, making him a pillar of the community as a whole. His book, TO DIE ALIVE, catalogues the complexities of queer identity both internally and externally on New York’s Fire Island; focusing on how queer people make their own spaces, interact with one another in these spaces, and interact with a landscape that is slowly eroding away. It is an honor to join him in conversation today about his practice and projects!

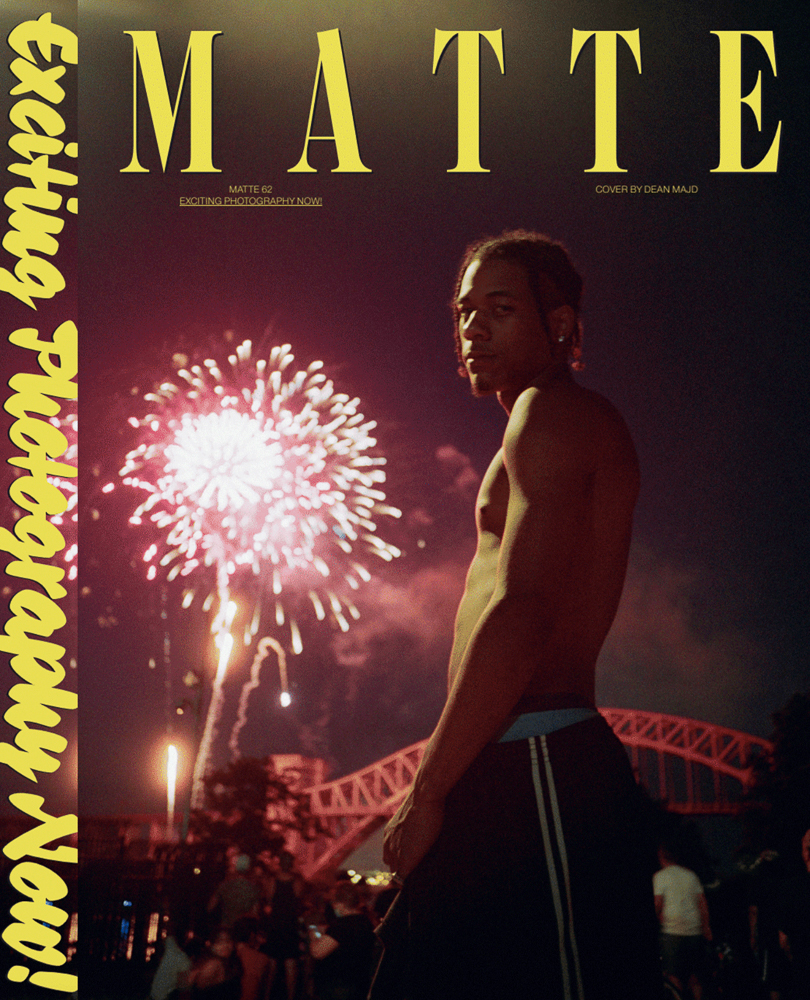

Matthew Leifheit is an American photographer, magazine editor, and professor. A graduate of Rhode Island School of Design and the Yale School of Art, Leifheit is Editor-in-Chief of MATTE Magazine, the journal of emerging photography he has edited and published since 2010. Leifheit was formerly photo director of VICE Magazine, and his photographs have appeared in publications such as The New York Times, The New Yorker, Aperture, TIME, and Artforum. Leifheit’s photographic work has been exhibited internationally and is held in public collections. He is currently on faculty at Pratt Institute and Yale.

Instagram: @mattelife

Paul: Fauller: Let’s talk about current happenings as of lately! So we have MATTE Magazine running as it has been, we have the MATTE Institute, and then you’re also teaching, which you’re going to be going to MassArt soon, I hear. I wanted to know- are you working on any personal projects as well?

Matthew Leifheit: I feel that all of these things were meant to feed my art practice, the teaching and the day jobs, and even the publishing of other people’s work. I think of it as something that’s a creative exchange. I am helping to mold people’s projects and distribute them, but it’s also the way that I’m engaged with my contemporaries, which I think is part of the responsibility of being an artist—to be in dialogue either through your work or through small press publications with other artists. So it’s all part of the same thing, but I just went through this season of publishing a lot. I published the Exciting Photography Now issue of MATTE Magazine, which had 85 artists, and a David Armstrong Fashion monograph which I co-edited with Vince Aletti. Then I also published a book, which was Art by Vicky West, who was an early illustrator of trans and BDSM subjects, and Jarrett Earnest’s Valid Until Sunset in the Winter.

So it’s just me doing the publications and it was sort of started as a hobby, but then there are these periods where it really comes to the fore. So I’m really happy to be in Florida. I’m in Key West for a month to focus on my own projects. This kind of self-directed residency for me where I’m staying at my friends’ beautiful house and the plan is just to read and go for walks.

I’ve found that for me as an artist, what I need more than anything is just like—I’m quoting a letter the poet Elizabeth Bishop wrote—where she writes that “what one seems to want in art, in experiencing it, is the same thing that is necessary for its creation, a self-forgetful, perfectly useless concentration.” And I think that what I came to Florida for is just undirected concentration to think about whatever I want, and I feel like since I’ve been doing so many projects that involve other people, that’s what’s been missing in my life.

I’m working on this big video piece about gay men’s choruses. That’s been the primary focus. Would you like to hear about that?

Paul: Yes, absolutely!

Matthew: I came to this idea at a residency last summer called Yaddo, which is in Saratoga Springs, and I had not been producing very much. I had been going on bike rides and sleeping a lot, honestly. And then one morning I woke up and my eyes fluttered open and I had this realization where I thought, gay men’s choruses. Why have I not done something with that? It’s such a fascinating concept, and I didn’t really realize where it originated or how it came to be, but I myself was a boy soprano and in a lot of choruses.

I realized I wanted to see a chorus of gay men performing during the decade that preceded Triple Cocktail, which was the first widely available effective HIV/AIDS medication, and I was thinking, what would it sound like for a group of men who are fearing for their lives to put on a Christmas show? Then I found out that none of it’s online, none of these tapes have been digitized, and there are a lot of reasons for that.

So I’m traveling to different archives to digitize these tapes. The shelf life of a VHS tape, even under good conditions, starts to deteriorate after 20 years, so I’m encountering things that are already very degraded and warped. I started out thinking, oh, maybe I’ll just look at Christmas holiday shows, but now it’s basically that there are very few tapes that exist because they were made for chorus members in those years. In Boston, they didn’t even video record the gay men’s chorus performances because people were worried about being outed at work, so they only recorded audio. So to find these video recordings, which are often something that’s been dubbed from different copies at home for other chorus members, has been really incredible. So now my mission is just to digitize them as widely and as fast as I can, then I’m making this installation that will be an endless looping gay men’s chorus recital that I’ve programmed. An eternal gay men’s chorus recital.

Paul: I want to talk about To Die Alive for a little bit because I have been resonating with this work lately. I’ve been very interested in the dialogues about age in the book and the relations between generations of queer people, especially as I feel like it’s getting more segmented between generations, and I guess, as a society in general. How would you describe the interactions between older and younger gay men on Fire Island?

Matthew:I mean, it’s a lot of what my interest is there, honestly. Hearing you say that confirms something that I believe to be true- there does seem to be kind of a widening gap between generations. The first time I went to Fire Island was when I was working at Vice. My friend Mitchell and I went there together to do this story about these underwear parties that they have where it’s like 600 guys in jock straps that are in this club environment. And I originally thought, this is not my kind of thing. And then I went out there and it was this one epic night that contained everything. In the back of my mind was like, I’m going to come back here and do something about this one day. But it was part of the story actually, that the underwear party was one of these rare instances where you get a lot of intergenerational mixing.

Part of that is the economics of Fire Island, where often the people who own homes are older men and women, and there’s younger people who are there as their guests or as sex workers or as sugar babies. There’s people who are coming out there who are young and renting houses together, and there’s old people who have been coming out for many years and will go with the same group of friends. But then at places like this underwear party, they all end up in the same room. It’s not like a utopia. There’s a hierarchy based on body appraisal and on ‘fuckability’ or whatever. And wealth is something that carries a lot of clout there. But it’s a place that I really love. Growing up in the 90s, I thought of all of these spaces as having been erased by the devastation of AIDS- so then to come out to Fire Island and find that there’s a very active culture, and still sort of in the same architecture, the same moldy, sagging architecture of what was there in the seventies, in the fifties even. I thought it was really fascinating.

So yeah, this one night that I spent there with the assignment. I wanted to go back and try to project everything that I had experienced that one night into a really baroque, epic descent. I think of the structure of the book as kind of a descent.

Paul: I also can’t help but think about just entitling your project “To Die Alive”- the “haunting” of Fire Island by those who had passed from HIV/AIDS and also getting confronted with ‘twink death’, or the ‘expiring’ of oneself in the gay community. I feel that all of those are very pertinent things that I can see in the book. You don’t actively see a twink dying, but metaphorical twink death is a very real, fear, and I think it’s embodied in a very beautiful way in the book.

Matthew: I love that. Thank you. I don’t know how long you get to be a twink, but it was probably photographed following my own twink death, in the wake of my twink era, which I never thought about.

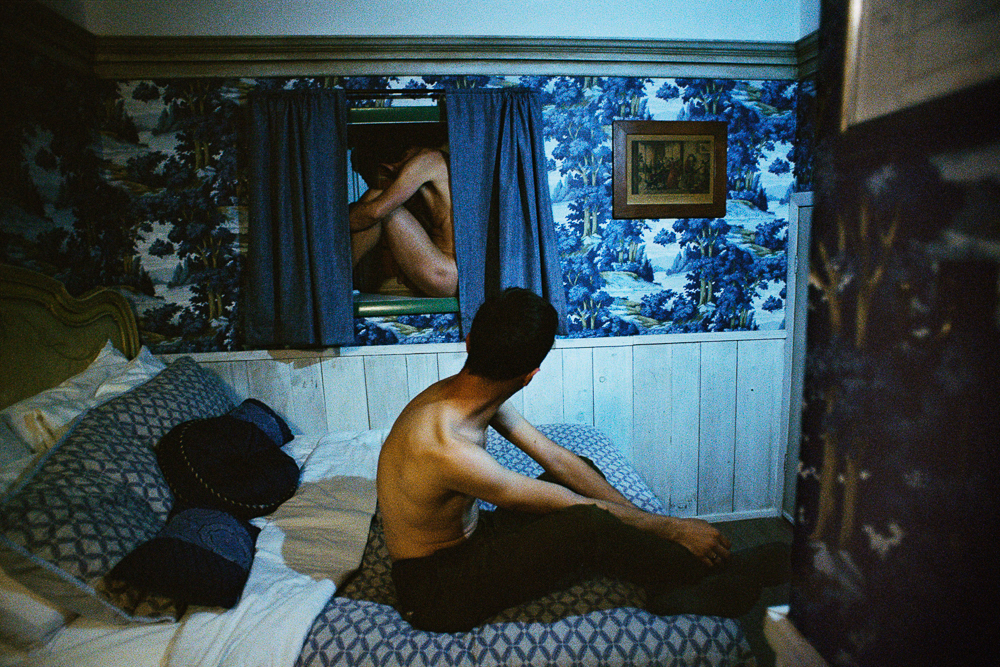

Paul: I also, in terms of just compositions, noticed you really like a person looking at another person looking either at you or at themselves. That is a very Matt image, I’ve seen. Is that intentional or is that a subconscious thing?

Matthew: Yeah, that’s very perceptive. I guess it’s one of my Easter eggs, everything I do has that. There’s at least one picture like that in each body of work that I have shown or published. It’s often something where there’s an intimate exchange going on between two people and the camera becomes involved somehow, where there’s someone who should be looking at the person they’re making out with, who is instead looking over at me. I feel like it’s a way of involving the camera and eventually the viewer in that circuit of desire that’s going on. I think a lot of the compositions are about this mapping of the desire that’s actually going on, or fabricating a web of desire that’s going on between the figures and the pictures.

Paul: I also wanted to hear your thoughts about the difference between queer internal versus queer external spaces. Queer domestic spaces are very curated, very meaningful to queer people. But then you also see these very present outward spaces on Fire Island where people can be voyeurs and people can watch. How did you visualize, or how do you visualize, I guess, the difference between those interior and exterior places?

Matthew: The places where I’m photographing were all built by a guy named John Eberhardt and are in Cherry Grove rather than The Pines. They are constructed out of trompe l’oeil painting and tape and cardboard and garden supplies, like garden urns and stacked up a certain way to look fabulous. But I wanted to exclusively use those interiors in my work and to just overlook the masculine mid-century architecture of the Pines entirely. I just didn’t include it at all.

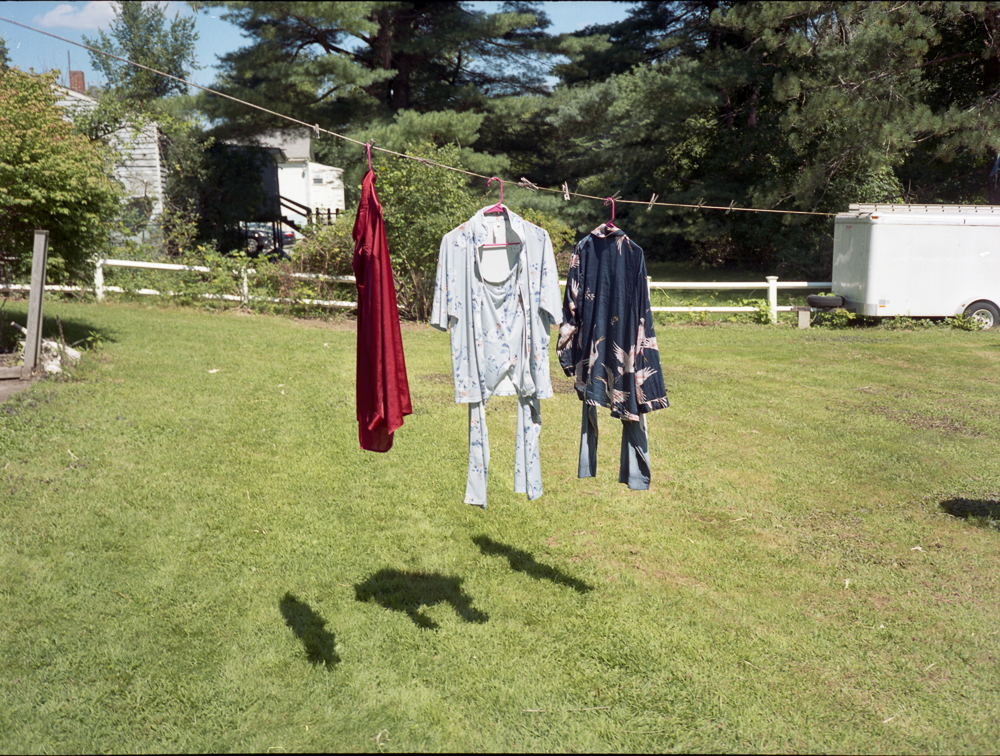

The exterior spaces are really what is so beautiful about Fire Island. The low landscape and those small twisted trees. I’m using a panoramic 35-millimeter camera for the horizontal landscapes that are in the book where it’s designed so that they just are kind of uncropped as full-bleed spreads, and I wanted to use that kind of camera because it fits with the landscape of the place- there’s no terrain. What surrounds us on Fire Island is really just the horizon. It’s this infinite space, which is one thing that when I was looking at the PaJaMa photographs, I thought about how surreal the landscape naturally is. It is a landscape in decline according to the National Park Service. The biological peak of the forest and the ecosystem there was in the 1970s, which is when an older generation might argue that gay culture also peaked, or that these places were at their best.

But really the thing is that it’s meant to wash away—it’s actually washing toward New York City, and the people who are there are doing their best to keep the sand on the beach; but the natural progression is that the Park Service estimates that fire island won’t exist longer than a hundred years from now. That seems like a generous estimate. So it was also something about just photographing this landscape that I perceive to be changing rapidly or disappearing, and to try and make my perfect depiction of it while I could.

The reason that they’re all taken at night outside and inside is because every depiction that I had seen of the place was this very sun-drenched vision, and it just didn’t seem to line up with what my experience of queer sexuality has felt like. Also, I love that it’s a place where many queer artists have worked and many people have photographed, but I wanted to stake out my own world within that and not have to worry whether my picture might look like someone else’s picture. And so I thought anything at night could be mine—there was a lot of freedom in that actually.

Paul: That’s beautiful. Very beautiful.

Matthew: I wanted to own the night.

Paul Fauller is a queer American photographer based in Boston. His work surrounds queer domesticity, place-making, and ideas of displacement. He is pursuing a BFA in studio arts from the School at the Museum of Fine Arts.

Instagram: @paulfauller

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

Riley Goodman: Art + History Competition Honorable Mention WinnerApril 4th, 2025

-

Rachel Nixon: Art + History Competition Honorable MentionApril 3rd, 2025

-

Oleksandr Rupeta: Art + History Competition Second Place WinnerApril 1st, 2025

-

Jared Ragland: Art + History Competition First Place WinnerMarch 31st, 2025