Photographers on Photographers: Emily Damyan in Conversation with Paloma Tendero

Every August we ask the previous Top 25 Lenscratch Student Prize Winners to interview a hero or a mentor, offering an opportunity for conversation and connection. Today we share a conversation with Emily Damyan and Paloma Tendero. Thank you to both of the artists.

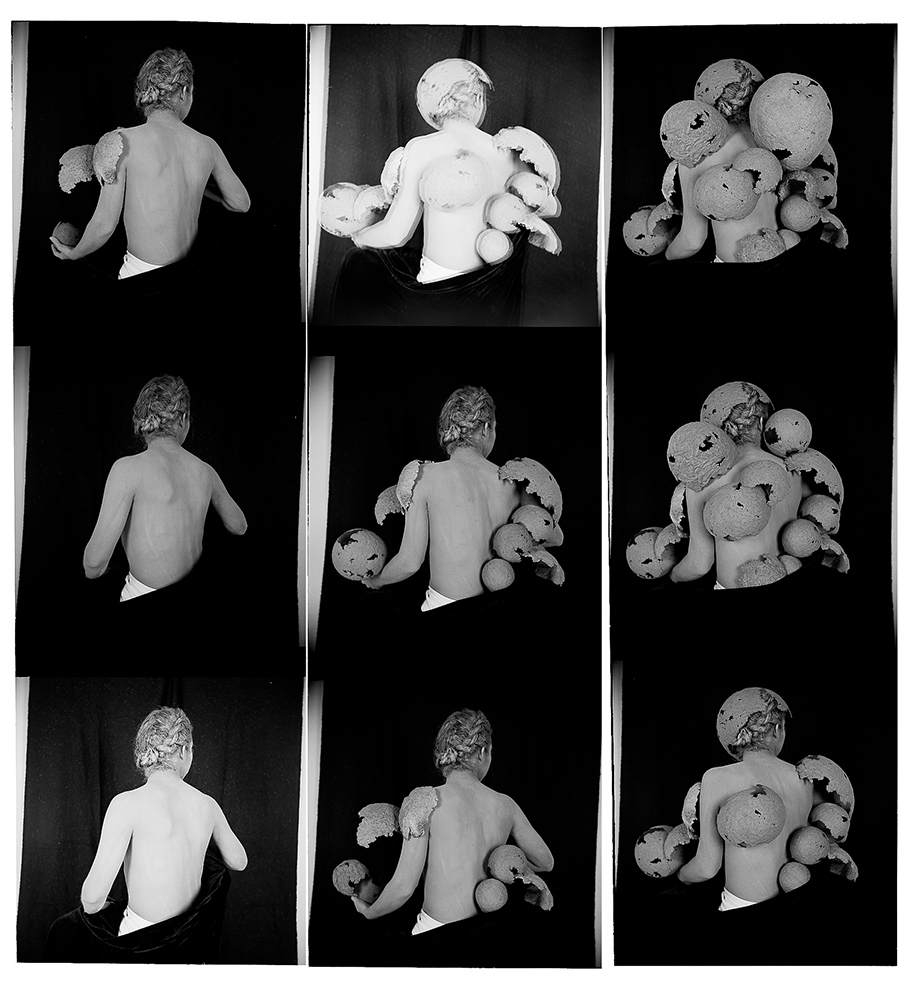

I was kindly introduced to Paloma Tendero’s work earlier this year by Cengizhan Sen, the founder of The Poorly Project. As soon as I was, I became curious to learn more about Paloma’s approach to photography and the combination of textiles and sculpture in her work. Particularly in her On Mutability project, which explores both fertility and genetic conditions using photography and sculpture in a compelling way that I hadn’t seen before. In preparation for this conversation, I realised that I wasn’t just curious about Paloma’s approach, I was also interested in how she continues to make that work over time. How she navigates the ups and downs of her creative process and what motivates her. It was refreshing to listen to Paloma talk about her work in how she refuses to shy away from the discomfort of being vulnerable in both conversation and in her practice. I’m incredibly grateful for her transparency in this interview, and I hope it offers something grounding to those who read it.

PRACTICE

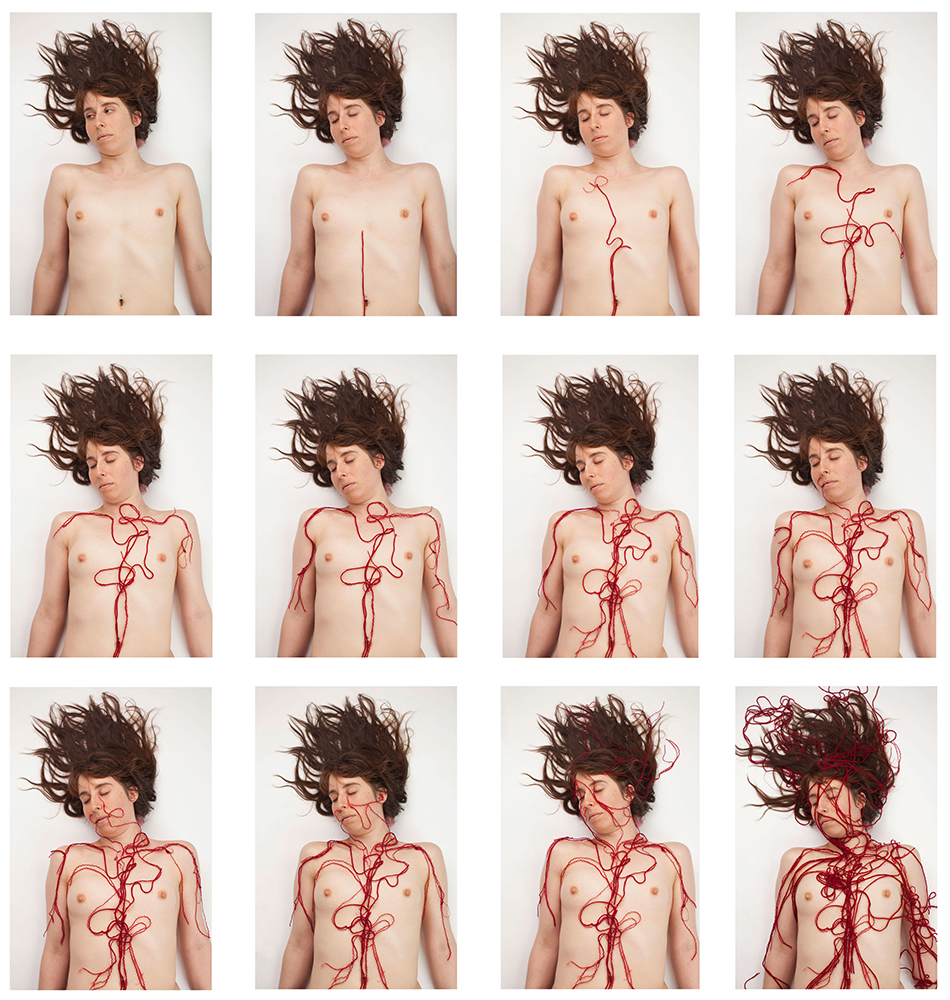

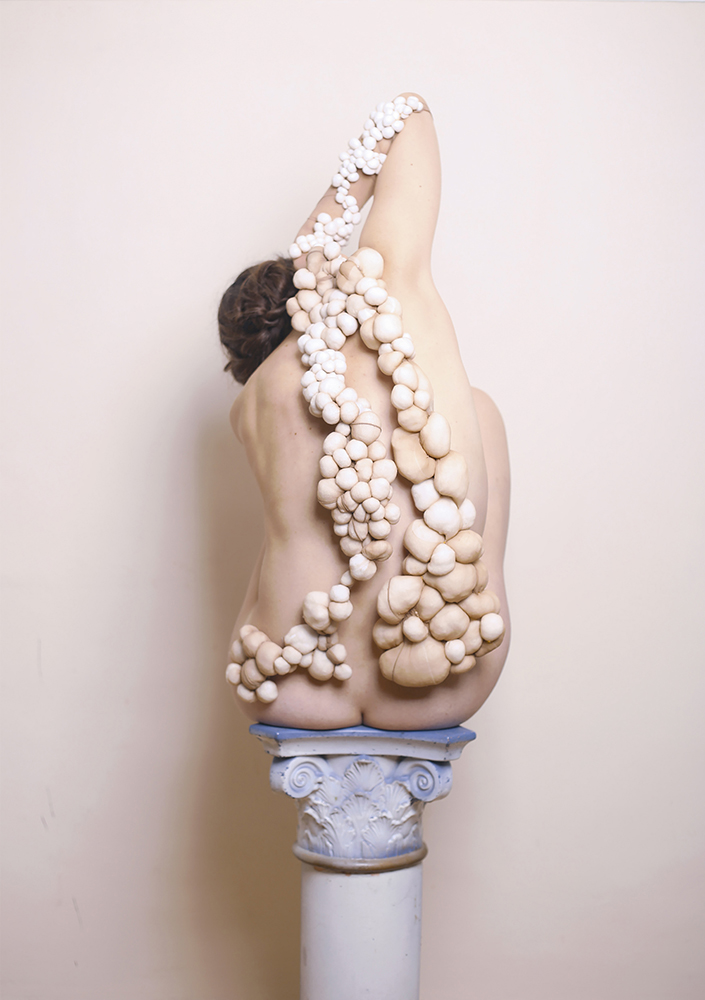

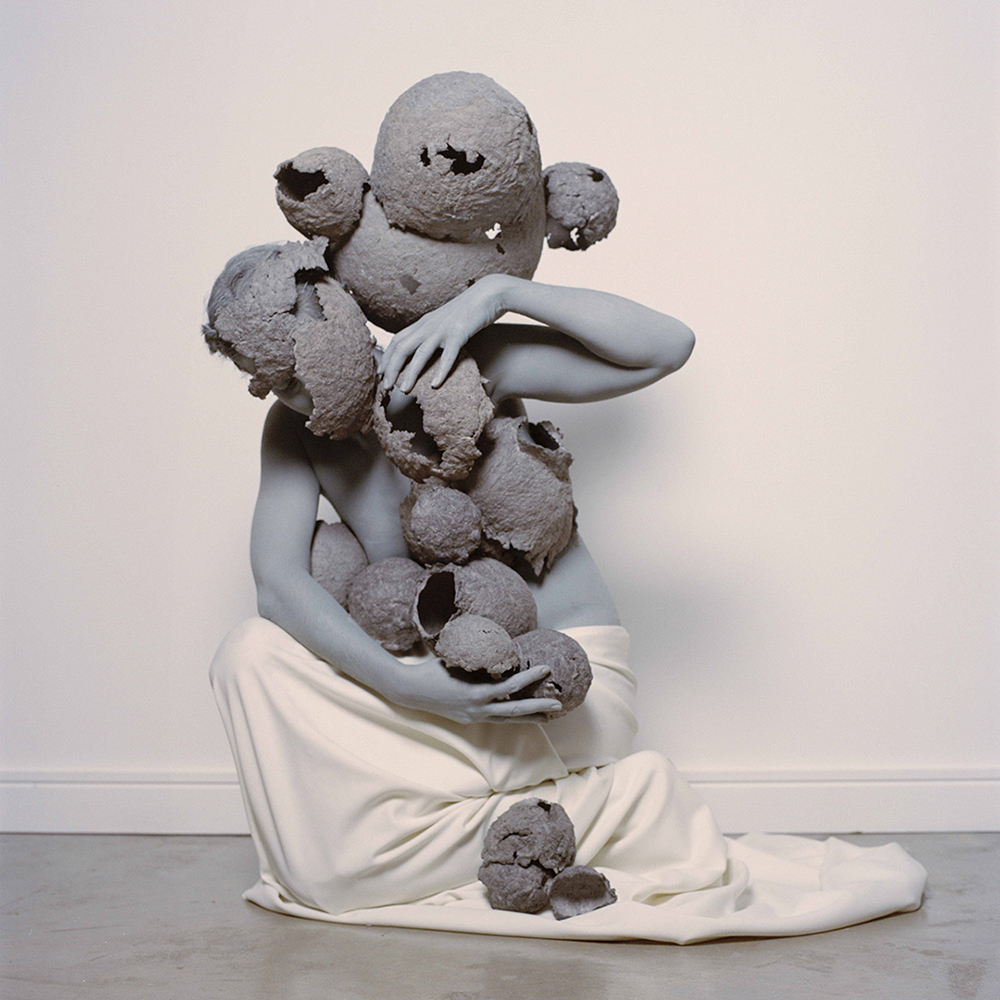

My artistic research explores themes around genetic inheritance, illness and the impact on identity and the timelines of life. Drawing inspiration from my personal experience with genetic illness, I explore the complex interplay between pieces of the past generations that shape the present and hold influence over its future. In my artwork, I liberate the body from the weight of yearning for perfect health, showing its natural vulnerability. I challenge the conventional association between health and beauty to represent the period of changes, pain and metamorphosis the body suffers with its lack of control, working around dualities: between the inside and outside, health and sickness and the transmutation from one to the other.

Those dualities – the union between two divided worlds – s where my art practices fall. By using photography, sculpture and mixed media practices, I play around with temporality, with the fragile existence of our bodies, and I reflect on the vulnerability of the physical shell, drawing parallels with classical references and our inherited cultural notions of the perfect body. By layering these concepts visually around my body, I aim to highlight the politics of body representation.

BIO

Paloma Tendero graduated from BA Fine Arts at Complutense University in Madrid and MA Photography at the London College of Communication. She has participated in artist-in-residence programs such as Sarabande, The Alexander McQueen Foundation in London 2020 and KulturKontak, the Austrian Federal Chancellery AIR 2018. In 2024, she was the winner of the 70:15:40 project UK.

Tendero’s works have been shown at Galleria Cavour, Padua, Italy 2019, Arnolfini Arts Centre Bristol 2021, Messums Gallery 2022, Centre for British Photography, London 2023, and PhotoLondon 2023-2025 and most recently at the University College London Hospital. She is also a facilitator in the Arts & Health Hub peer groups to support artists and creatives exploring health and wellbeing in their practice.

Instagram: @palomatendero

For those who aren’t already familiar with your work, how would you describe it?

I am a visual artist interested in the perception of the human body, questioning associations between health, illness and beauty. I explore inheritance and its impact on identity and the timelines of life. I often use photography and mixed media as a medium of expression.

I’m curious, what drives you to create what you make? Are there recurring questions, feelings or ideas that you return to?

I often examine the lack of control over the body, drawing inspiration from my personal experience with genetic illness and the experience of others around me. I have chronic kidney disease, and that has played a part in my upbringing. My grandmother and my mother passed away due to this illness, so I try to understand the pieces from past generations that shaped my body, the cultural ideas we inherited and the notion of the perfect body. Trying to liberate the body from the idea of perfect health, showing its natural vulnerability and accepting the periods of transformation and change.

With this in mind, what does your process usually look like? Do you tend to work alone or with others? Are your projects usually self-funded or shaped by certain materials or limitations?

Everything starts with playing and making objects. Making sculptural pieces is a very organic process for me. I just play with the material and forms without putting much pressure on the result. I try to follow my instincts and what my body wants to make. It’s like I have an emotion I need to explore, finding a physical form. I often do repetitions until I get tired or I run out of space.

Then I plan photography sessions. The work is a process of interacting with objects I have created, things that don’t exist in everyday life. I make things that don’t have a place in reality, like a way of representing what’s going on inside my body. I usually have some help during the shoots, especially for self-portraits, as it’s physically difficult to manage both the camera and multiple sculptural elements at once.

Most of my projects have been entirely self-funded, except the last one, which was supported by the award I received. This has shaped my way of working, and I usually use recycled materials in my projects.

This project really stood out to me, particularly for its combination of the self-portrait and sculpture, but also for how it questions both fertility and illness. Do you see this work as part of a broader conversation about how we view and question the body, particularly concerning illness and reproduction?

Yes, I think my work is very much part of a larger conversation about how we conceptualise and represent the body, especially regarding illness, reproduction, and inherited traits. I am interested in how something as intimate as fertility can also be shaped by cultural expectations. My work responds to this by creating space to hold that tension, balancing papier-mâché eggs made from recycled egg cartons. I seek to convey the concept of bearing the physical and psychological weight of the world on one’s shoulders.

So, would you say that you use photography as a kind of therapeutic process for you? Maybe making sense of what you’re navigating or have previously experienced?

I find photography very cathartic. In general, I use art to question things and open up space for conversations that would be awkward in many other environments. Photography is like a mirror, sometimes uncomfortable, sometimes gentle, that helps me see and accept different parts of myself. I think there’s something powerful in framing your own body or experience, literally and metaphorically. Through photography, I can slow things down and make sense of emotions or realities that might otherwise feel out of control.

That really resonates with me. In my own practice, I often find that creating helps me communicate things I can’t easily put into words, like it becomes its own language. Your work also feels very personal. Is that something you relate to?

Yes, totally. My art is an extension of what’s in my head, or what’s in my body, basically. I am a visual person, and making art helps me process vulnerability and strength.

It’s great to see that you were a part of the 70:15:40 Project UK in 2023, which highlights the underrepresentation of women, trans and non-binary people within photography. Thinking about that alongside the broader disparities within photography and from sustaining your artistic practice, is there anything that you wish you’d known earlier on?

One thing I have learned is the importance of patience. Opportunities don’t always come when you expect them to. That’s why I think it’s important to use the quieter moments when nothing is happening to prepare yourself, instead of getting frustrated that things aren’t happening yet. I wish I had known earlier that these pauses can actually be productive, and that the right opportunities will come if you keep working and stay ready. For example, I received the 70:15:40 award just a few months after signing a full-time contract, but I applied with a project I wanted to do for a long time, so I embraced the moment to make the most of it, as often everything comes all at once.

I appreciate that, as it is difficult to move forward after receiving rejections. When you do find the time, is there something that you want to explore even if you haven’t yet?

Right now, I am curious about layering, painting and collage and experimenting with how different materials can carry meaning and memory.

I’m looking forward to seeing this unfold. Is there anyone in particular who inspires you or influences the way you think about your work? Other artists, writers, etc.?

I am inspired by artists such as Louise Bourgeois, Helen Chadwick, and Kiki Smith. I admire how they represent the body and identity, capturing intimate experiences while challenging societal norms. Alongside visual artists, writers like Susan Sontag and Caroline Crampton have shaped my thinking as they beautifully explain my exploration of fragility, perception, and the changing body.

Emily Damyan (b.2000) is a Turkish-British born artist who works with photography, sculpture and mixed media. Her work explores the intersections between health, biopolitics, and identity through personal experiences. She graduated in 2024 from the University of East London, where she exhibited her award-winning exhibition ‘The Weight of Silence’. She has been selected as part of the Lenscratch Student Prize Top 25 to Watch (2024) and was part of the Photo Fringe Festival (2024), where she received the Danny Wilson Prize (2024). She lives and works in Nottingham, UK.

Instagram: @emily__damyan

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

Ricardo Miguel Hernández: When the memory turns to dust and Beyond PainNovember 28th, 2025

-

Pamela Landau Connolly: Columbus DriveNovember 26th, 2025

-

KELIY ANDERSON-STALEY: Wilderness No longer at the Edge of ThingsNovember 19th, 2025

-

Jackie Mulder: Thought TrailsNovember 18th, 2025