Aiko Wakao Austin: What we inherit

I only recently became acquainted with Aiko Wakao Austin. We were both selected in the Lensculture Critics’ Choice 2025, and given a Top 10 award. As I scrolled through the winners’ gallery, I really paused on Aiko’s work and immediately had to follow her on Instagram. The use of archival photographs and patterns creates successful and intriguing layers. As an artist who also works with old family photographs, I am always interested in how others explore these ideas. Going a bit deeper, the history of Japan in the early twentieth century is wrought with political and social explorations, ones which Aiko successfully embeds within her work. Spend some time with these and see what you can find, in reflecting with your own family ephemera.

Aiko Wakao Austin (若尾 藍子) is a Japanese photographer and translator in New York. Born in Tokyo, she spent her childhood in Italy and studied International Relations at Brown University. Earlier in her career, she worked as a journalist in Japan, and later in finance where she covered stories about Japanese companies and markets. She moved to New York in 2016 and began photographing professionally and working as a translator. Reflecting her multicultural upbringing, her personal projects explore the concept of identity, family and culture. Her latest work,, “what we inherit,” was selected for the Julia Margaret Cameron Award in 2024, and LensCulture Critics’ Choice Awards – Top 10 Winner and Photolucida Critical Mass Top 200 in 2025. It was also exhibited at Photoville in NYC and Vision(ary) public art show by Griffin Museum in Winchester, MA in 2025. She lives outside NYC with her husband and two children.

Follow Aiko on Instagram: @aikowakaoaustin

What we inherit

My photography explores the intersections of identity, memory and culture. Having moved between Japan since childhood, I have always experienced culture as something fluid—shaped as much by distance and absence as by presence. This sense of “in-betweenness” informs the way I see and photograph the world.

I am also drawn to the stories held in physical objects that carry the marks of time and use. Through my work, I try to trace the imprints left by those who came before us, and to understand how traditions and rituals shape our sense of self. By documenting these details, I explore how culture is passed on, and reinterpreted across generations. Photography allows me to bridge past and present, making space for narratives that are both personal and collective.

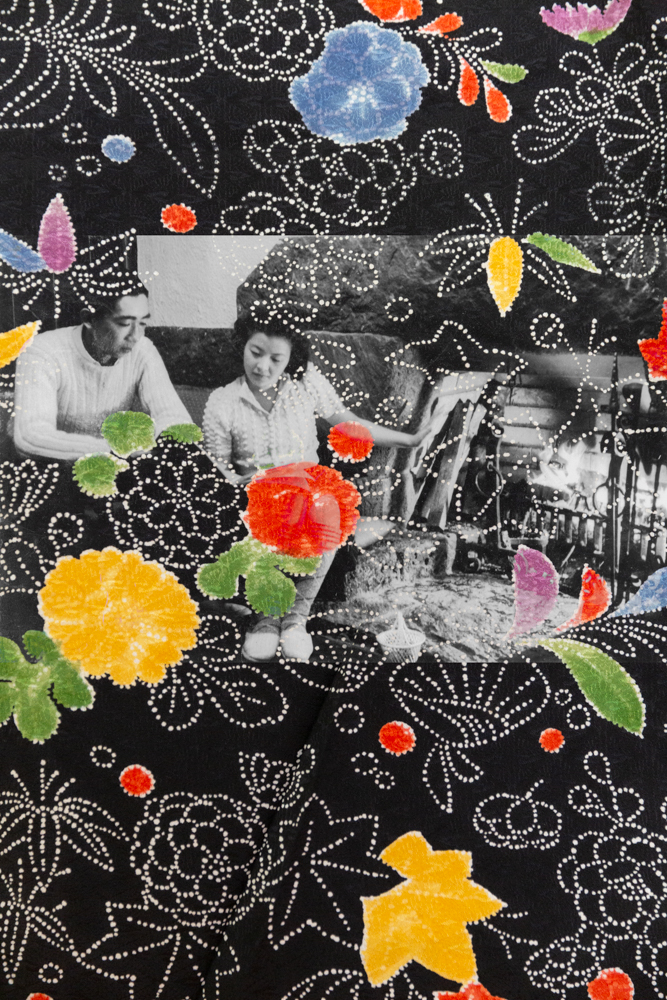

“What we inherit” is an artistic exploration of legacy, culture and tradition through my Japanese heritage. Using kimonos and scrapbooks that my grandparents left behind from the 1930-60s, the photographic montages represent a family’s memories and emotions that have been passed down, but are also slowly fading.

My grandmother, a lover of luxury despite the family’s financial struggles in postwar Japan, continued to commission exquisite kimonos. Many were crafted from fine silk and adorned with intricate embroidery. It was perhaps her means of self-expression or how she defined her place in society. Forty years after her passing, what is left of her inheritance has traveled with me to America.

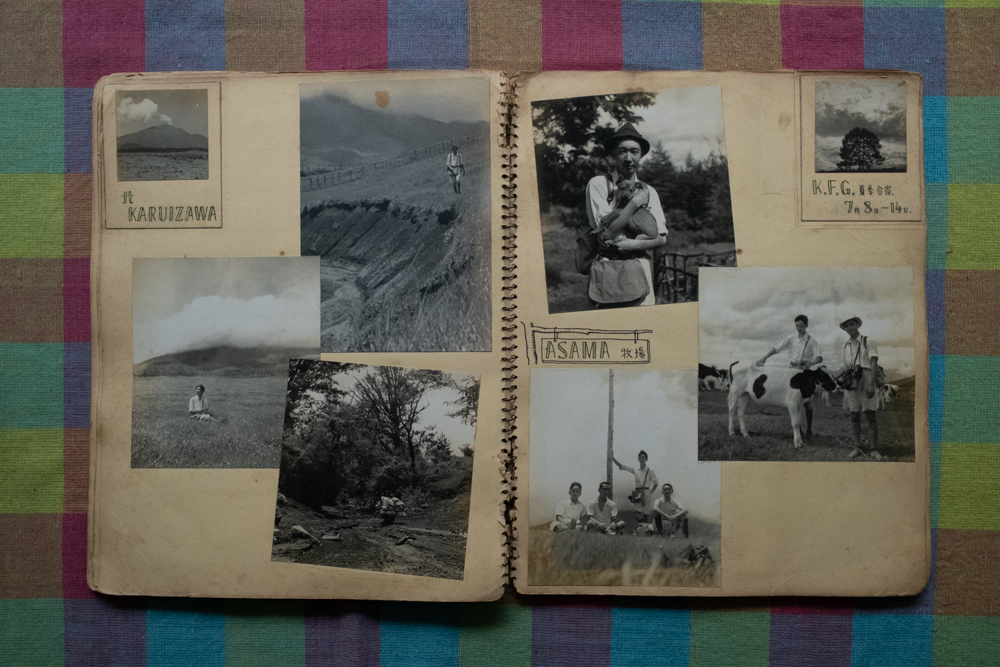

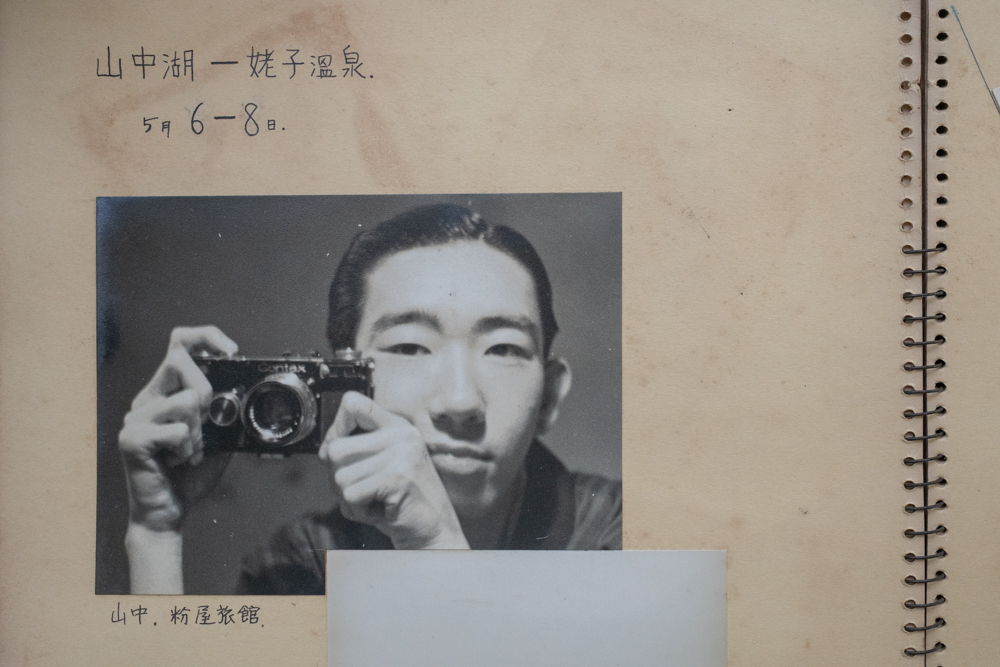

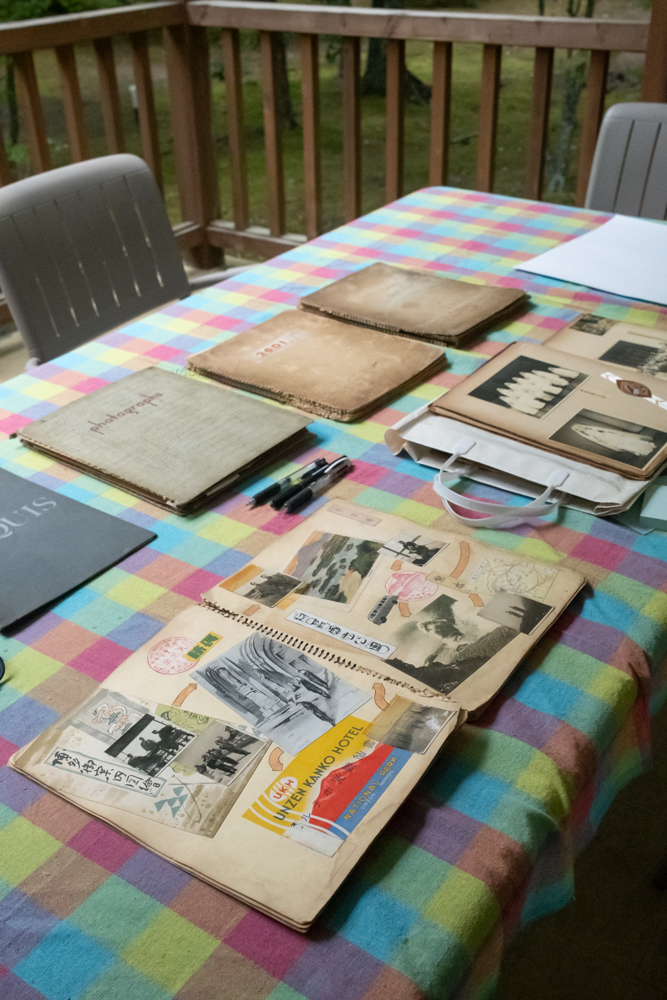

My grandfather, a television producer in Japan’s early broadcast era, was a devoted documentarian of his own life. His meticulously compiled scrapbooks, with photographs of himself and his family, reveal glimpses of a rapidly modernizing society. Though he passed away years before I was born, his visual records have passed on pieces of his life to me.

My image-making process involves photographing the kimonos during mushiboshi, a tradition of airing the delicate fabric during the dry months. The garments are photographed in natural light and merged with scanned archival photographs. In layering photographs and textiles, I aim to visualize the layers of time and meaning we carry within us.

Storytelling, particularly across generations, is an act of care. It allows us to tether ourselves to something larger than our individual lives. It helps us make sense of who we are and where we come from. By bridging the past and present, this project seeks to preserve one’s tangible history, and reimagine its place in today’s digital culture.

Epiphany Knedler: How did your project come about?

Aiko Wakao Austin: This project started from the feelings I was having after leaving Japan nearly nine years ago. We moved to the U.S. with our daughters when they were still very little, and while it was the right step for our family, I struggled with the distance from my parents. I also felt sad that my girls were missing the chance to grow up in Japan. So going back every summer became important, and during those visits I began sorting through my grandfather’s scrapbooks that had been gathering dust in my parents’ apartment. He was a TV producer in Japan’s early broadcast era and kept a meticulous record of his life with scrapbooks filled with postcards, photos and sketches. At the same time, I started looking through my grandmother’s kimonos, which she left to me before her passing. At the end of each trip, I would carry back as many albums and fabrics as I could fit into my suitcase.

In New York, caring for the kimonos became a seasonal ritual. I practiced mushiboshi, the late-summer airing of garments to get rid of moisture and insects. I would notice creases, stains and the lingering smell of mothballs that reminded me of my grandmother’s closet. As I archived these items, I began thinking about how to share them with my daughters in a meaningful way. I wanted to leave behind something they could understand and connect with; so that they remember a story that mattered to me.

That’s when I started photographing the kimonos and scrapbook pages and layering them into collages. It felt very natural, almost intuitive, responding to the shapes and colors in the fabric and the moments in the photos. Making them digital was also important, since that’s the world my kids are growing up in. What began as a way of holding onto my family’s story became a way of passing it forward.

EK: Is there a specific image that is your favorite or particularly meaningful to this series?

AWA: I’d probably choose A Family Portrait. Out of all the photographs I’ve found, this is the only one with all five family members together. Judging by their ages, it must have been taken in the late 1940s. They’re all dressed up, likely for a special occasion—or perhaps simply for the photo itself. My grandmother was particular about appearances and took pride in dressing properly, even during difficult times. There’s a quiet formality in their expressions, a kind of composure that reflects the values of that generation.

This photo has also taken on more emotional weight since my uncle—the youngest child in the photo—passed away this spring. Now, only my father remains. Seeing this image now is a reminder that everything in life has a season, and one generation inevitably passes the baton to the next.

EK: Can you tell us about your artistic practice?

AWA: Because of my background in journalism, I tend to work by intertwining words, research and images. I spend a lot of time documenting or gathering information about what I photograph, and this process helps me clarify my intention and how I want to express it. What often strikes me is that after sifting through a mountain of words and research, I am left with something very simple.

My work is also shaped by my multicultural upbringing. Moving in and out of Japan as a child, I have always searched for meaning in the spaces between cultures. Taking my translation work for example, it’s never a simple substitution of words but an interpretation of ideas within a new context. I think photography works in a similar way, and this way of seeing has become a fundamental part of my art.

EK: What’s next for you?

AWA: “What we inherit” started as something very personal, and I honestly didn’t expect much response outside my family and close friends. One of the most rewarding parts of showing the work has been the conversations it sparks. People often share their own family stories and items they inherited. These conversations remind me how universal these themes are.

My next focus is to bring the project to more places, especially minority communities where the experience of migration is felt most directly. I’d also love to work with students, encouraging them to ask questions about their heritage and see the value in keeping those stories alive.

Right now, I’m also working with a printer in Japan to make editions on traditional papers and fabrics. It’s exciting to bring the project back into the physical world, and explore new ways of presenting it as artwork, but also as something that carries cultural meaning.

Epiphany Knedler is an interdisciplinary artist + educator exploring the ways we engage with history. She graduated from the University of South Dakota with a BFA in Studio Art and a BA in Political Science and completed her MFA in Studio Art at East Carolina University. She is based in Aberdeen, South Dakota, serving as an Assistant Professor of Art and Coordinator of the Art Department at Northern State University, a Content Editor with LENSCRATCH, and the co-founder and curator of the art collective Midwest Nice Art. Her work has been exhibited in the New York Times, the Guardian, Vermont Center for Photography, Lenscratch, Dek Unu Arts, and awarded through Lensculture, the Lucie Foundation, F-Stop Magazine, and Photolucida Critical Mass.

Follow Epiphany on Instagram: @epiphanysk

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

Carolina Baldomá: An Elemental PracticeJanuary 5th, 2026

-

Time Travelers: Photographs from the Gayle Greenhill Collection at MOMADecember 28th, 2025

-

Suzette Dushi: Presences UnseenDecember 27th, 2025

-

Ragne Kristine Sigmond: Portraits of Painterly LightDecember 2nd, 2025