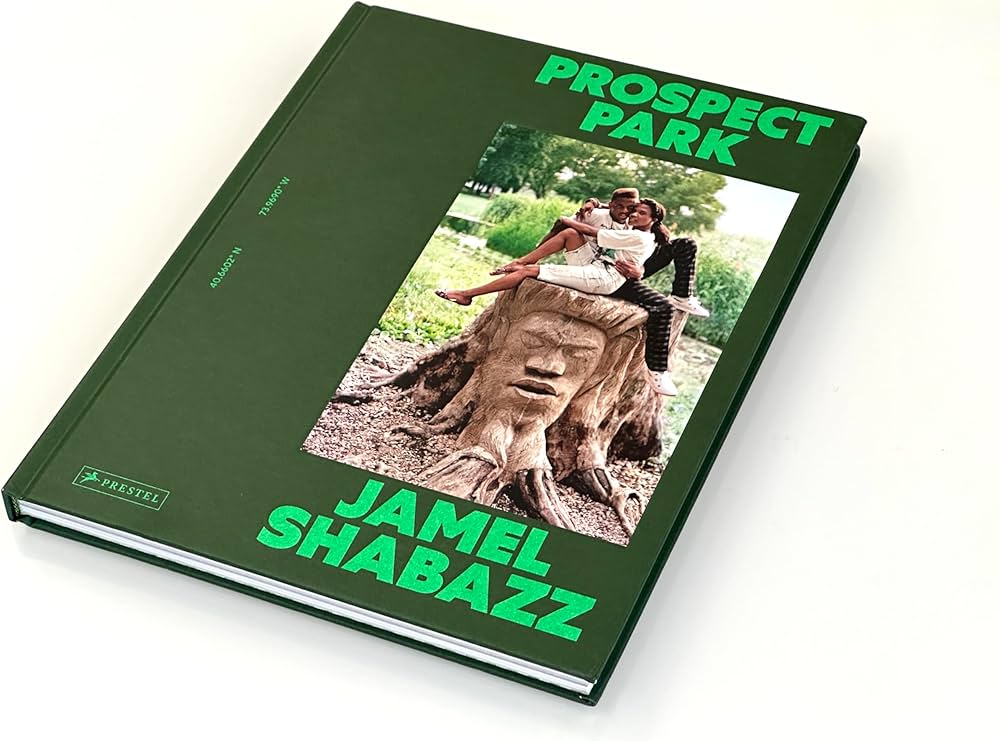

Jamel Shabazz: Prospect Park: Photographs of a Brooklyn Oasis, 1980 to 2025

I can’t remember when I first saw the work of Jamel Shabazz, but I’ve known of him for years and I was really honored to have my work alongside his in the 2023 New York Now: Home exhibition at The Museum of the City of New York. In early October of this year, we were both featured artists in the Dear New York exhibition curated by Brandon Stanton of Humans of New York in New York City’s Grand Central Station, and we talked at length about collaborating in the future: he’s a former corrections officer and I’m a former criminal defense attorney and we both have bodies of work around incarceration. But it’s his new book, Prospect Park: Photographs of a Brooklyn Oasis, 1980 to 2025, published by Prestel, which is a division of Penguin Random House, that I was eager to talk to him about after I went to one of his book talks where he showed slides and was in conversation with Noelle Theard (Instagram:@noelleheard) of The New Yorker.

Shabazz states:

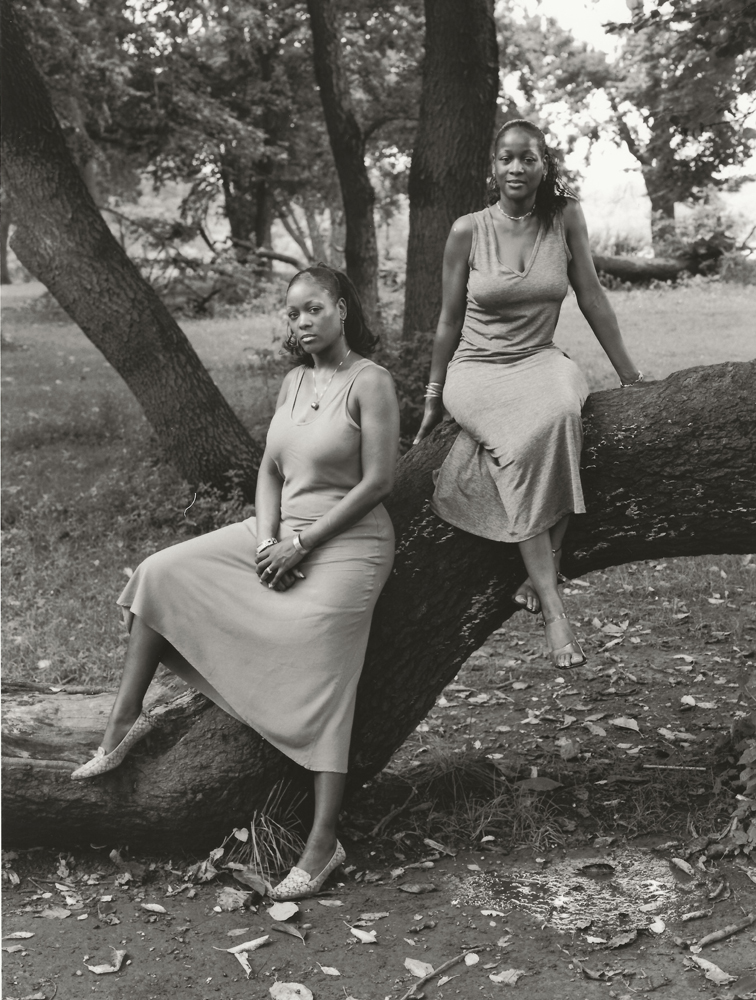

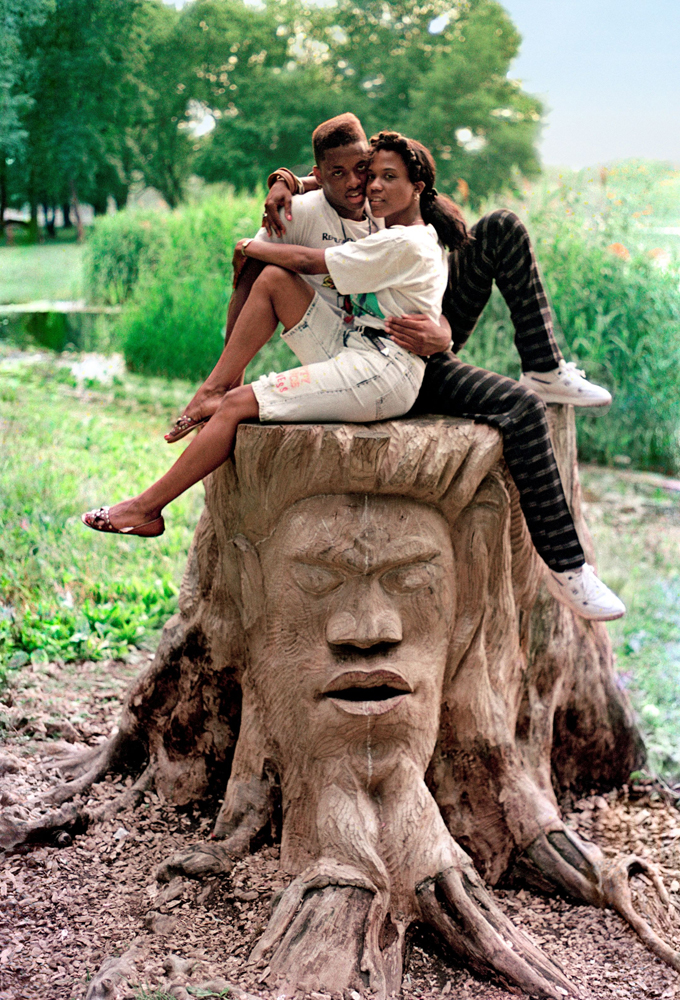

I started photographing in Prospect Park during the summer of 1980. I was freshly home from being honorably discharged from the United States Army after completing a thirty-six-month tour in West Germany. As a former soldier who was accustomed to physical training every day, I decided to maintain my discipline and run at least four days out of the seven-day week. I started bringing my camera on every run and the whole experience put me on a spiritual journey of self discovery.

Please join Jamel Shabazz in conversation with Laylah Amatullah Barrayn on Tuesday, January 27, 2026, at 6:30pm at the Center for Brooklyn History. Jamel Shabazz will kick off this year’s “Behind the Binding” artist talk series at Leica Store and Gallery New York on Saturday, January 31, 2026, at 11:00AM.

An interview with the artist follows.

Jamel Shabazz is best known for his iconic photographs of New York City during the 1980s. A documentary, fashion, and street photographer, he has authored 12 monographs and contributed to over three dozen other photography related books. His photographs have been exhibited worldwide and his work is housed within the permanent collections of The Whitney Museum, The Studio Museum in Harlem, The Smithsonian’s National Museum of African American History and Culture, The Fashion Institute of Technology, The Art Institute of Chicago, the Getty Museum and the National Portrait Museum. Over the years, Shabazz has instructed young students at the Studio Museum in Harlem’s “Expanding the Walls” project, The Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture “Teen Curator’s” program, and the Bronx Museum’s “Teen Council.” He is the 2023 recipient of the Lucie Foundation award for his achievement in documentary photography, and the 2022 awardee of the Gordon Parks Foundation / Steidl book prize. He is member of the photography group Kamoinge. As an artist, Shabazz is determined to contribute to the preservation of world history and culture.

Instagram: @jamelshabazz

Sara Bennett: You and I are both long term Brooklynites and share a deep love for Prospect Park. For those readers who aren’t from Brooklyn—because, let’s face it, even people from the other Boroughs don’t come to Prospect Park that much—can you tell us just a little bit about the terrain of Prospect Park and the people who frequent it.

Jamel Shabazz: Prospect Park is considered the little sister to Central Park, and was designed by the same Frederick Olmsted and Calvert Vaux who designed Central Park. Prospect Park officially opened in 1867. It is the second largest park in Brooklyn, with Marine Park being first. The park is 585 acres, there is a beautiful picturesque lake, a zoo, an ice skating rink, and a large concert band shell that has hosted some great concerts and plays over the many years. The park is frequented by the local, diverse communities from the surrounding neighborhoods, and it has been reported that the park gets approximately 8 – 10 million visitors a year.

You’ve been photographing in Prospect Park since the early 1980s, which is just after I arrived here. I love so much about your book — the changing styles, the black and white and color, the relationships among the people you photograph and their comfort level with you, the changing landscape. When you started out, did you have any idea that you would be embarking on such a long-term project?

I had absolutely no ideal at the time that I would undertake such a long term project. I came upon that realization just a few years ago when I started revisiting the photographs I made over the many years.

Has the Park changed over the years?

The park, in my opinion, has not changed too much, but through The Prospect Park Alliance and dedicated volunteers who help to maintain the park, it is so much cleaner than it was during the 1980s. I started seeing a noticeable change in the people embracing the park throughout the 1980s and 1990s, first with the influx of refugees from South Vietnam who were given housing in the vicinity of the park. They were actually some of the first people I photographed outside of my own community. What I found interesting was how they enjoyed the park, for it was the closest landscape that reminded then of their country. As time progressed, I started seeing large families from the former Soviet Union bloc countries, and later on a lot of people from Bangladesh and Pakistan.

That’s what I love most about the park, especially on weekends in the summers. Every type of food is being cooked, every type of music is being played, and it feels like a conversation between cultures.

Today walking in the park is like going to the United Nations; so many cultures and communities are represented, including implants from other states in this country.

How do you keep track of who you’ve photographed?

My system is organic, I always kept a small notebook and pen with me, and wherever possible I would get contact information. Back in those days, a lot of folks had business cards, and they would pass them on to me, I would then put the date and description of the photo on the back of the cards. I’ve maintained those cards and notes till this very day, which has been extremely helpful in remembering people and archiving my work.

That’s amazing to me. I think of myself as organized, but certainly not like that. The people you photograph are so relaxed and you have such a rapport with them. How do you do that?

The main technique I use is to communicate with those I wish to photograph, state my intentions, show a genuine concern about their well being, and show them samples of my work in a portfolio I always carried with me. Once the trust was established I would make the image, pass on my business card, and make arrangements to give them a copy of the photo at no cost if they contacted me. Building relationships with my subjects allowed me to photograph some of the same people again, and in many cases build friendships that I still have today.

I understand you put together this book during COVID.

Yes, the idea came upon right around the time that COVID hit; it was during that time I decided to spend more time at home and redirect my time and energy towards organizing my vast archive. I first started going through all of my photo albums, and separating images according to themes, and Prospect Park was one of the very first themes I decided to start with due to the large amount of time I spent in the park going back to the Summer of 1980. Once I gathered up those original 4 x 6 prints, I created a few new photo albums centered entirely on that body of work. After completing that process I started going through my all of my negatives, locating and scanning images from the park, and once that process was complete I did the same with all of my slides. Upon gathering up all of the photos and negatives, I started the editing process of selecting the images that would work for the book. Once that process was complete, I then presented them to Prestel and they took it from there.

You’ve been published by a variety of presses, from Damiani to Power House and now to Prestel, which is a division of Penguin Random House.

I ‘ve been fortunate to have worked with a number of great publishers over the years, and I am forever thankful to Powerhouse for accepting a number of my book proposals, the main one, Back in the Days in 2001 that would jump start my career as an author. With Prestel publishing, to my surprise, around the summer of 2024, Ali Gitlow the NY senior editor at Prestel reached out to me, and asked me if was I working on any book projects. In looking at all of the potential book projects I could have produced, I decided that my Prospect Park body of work would make a decent book, so I shared the idea with her along with samples of the work, and shortly afterwards the project was green-lit, and a little over a year later, Prospect Park: My Oasis in Brooklyn was released. I did most of the editing, but I also worked with Rush Jackson who was commissioned to design it and Ali Gitlow who assisted in the overall process. There were a few bumps in the road, mainly when it came to having the right size files, but other than that it was a great process, and I gained a wealth of knowledge from the experience.

I also want to talk a little about the essays in your book, since they capture so much of my feelings about the park. Like Layla Amatullah Barrayn, I’ve been riding my bike around the loop for decades and she so eloquently captures the “convergence of people from all walks of life.” Richard Green’s description of Drummer’s Grove is so vibrant and joyful; Noelle Flores Theard writes a beautiful tribute to you as the “embodiment of a long line of Black aesthetic creativity” ; and you not only let us in on your own background, your interest in the park, and the solace and peace you find there, but you also end the book with a wonderful, “Love Letter to Prospect Park.”

I decided to have a few essays in the book to give it more gravity.I had a personal connection to each writer. With Richard Green, it was meeting him in the park for the very first time, and knowing that he was both a Vietnam Veteran and also one of the original drummers at Drummer’s Grove. I invited Laylah because she grew up in Brooklyn and has a personal connection and appreciation for the park, from childhood to her adult years. And I invited Noelle because she wrote her thesis on my work 10 years ago, and I also had the pleasure of photographing her and her colleague in the park years ago. With my writings, I felt it was important that I share my personal voice to the book so that the reader would have a greater understanding of my work and journey.

To my eye, even decades ago when you were very young, you were already photographing with intention and with an incredibly good eye. Did you have any training?

My eye has changed a lot over the years, I started out as a street and portrait photographer, a genre I would practice throughout much of my career. For the past 15 years I have been drawn more to fashion and set photography. With those forms of photography I can be more creative and fluid. Regarding training, I was taught by my father, who was a professional photographer by trade, specializing in studio, portrait and wedding photography. He provided me with a solid foundation in the craft, teaching me everything from understanding light, compositions, subject matter, and the fine art of print making.

When did you first pick up a camera?

I started making photos when I was 15, using my mother’s Kodak Instamatic 110.

I know you’re a mentor to many up-and-coming photographers, as well as young people in general. What kind of advice to you give?

The main advice I give is: first, to be respectful towards all the people you want to photograph, second, consider using your gift to take on issues that are close to your heart, third, be diverse and build a comprehensive body of work, don’t limit yourself, and lastly, carry your camera everywhere you go.

Did you have any mentors?

Brooklyn born documentary photographer Joseph Rodriguez, who I’ve known for 20 years, is the one person I consider a mentor. I was introduced to his photography by his book Spanish Harlem. It was in the pages of that book that I realized that I might be able to create a similar book about my community. A couple of years later I met him at a book fair, and he broke down his creative process, along with the challenges of working in the publishing industry. He stressed the importance of getting close to your subjects, and if possible try to get into their homes to document more intimate images. His advice has been very instrumental in helping me become a better photographer.

This is a question I’ve never asked before but the New York Times always asks it of its authors and so I want to ask you: You’re organizing a dinner party. Which three people, dead or alive, do you invite and why?

I love that question. My three guests would be my parental grandfather, my father and uncle Charlie. All are deceased and have been for some time. Both my grandfather and uncle were World War II veterans and had roots in the south. I had a great relationship with both of them. But I was too young at the time to really ask them questions about their lives and personal experiences in the war. I knew that my grandfather served in the US Army in Burma in the mid 1940s, and my Uncle Charlie served in the US Navy and was stationed at Pearl Harbor, also in the 1940s. There is so much history with both men, but sadly a lot of it was lost with the passing of so many elders within my family. And with my father, I never really made the time to talk to him about his life, particularly as a navy photographer, and his experience serving on the USS Intrepid during the 1950s. At my dinner party I could act as an investigative reporter and ask all three endless questions about their individual journeys and the life lessons they learned.

What’s next for you?

Currently I’m working on a bunch of new projects — the main ones are short films & plays based off my personal experiences over the past 50 years. They are all works in progress, and a major learning curve for me, but I’m determined to bring them all into fruition in due time.

Oh, so you’re turning to writing. That’s so fabulous! I’m sorry this interview wasn’t earlier so that people could give your book as a holiday present, but I think it would make a perfect Valentine’s Day present because, as you inscribed my book, “love is the message.”

SARA BENNETT, a contributing editor to Lenscratch, is a 2024 Guggenheim Fellow in photography. Her first monograph, Looking Inside: Women with Life Sentences, is coming out in 2026.

Instagram: @sarabennettbrooklyn

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

Amy Friend: FirelightFebruary 25th, 2026

-

Philip Toledano: Another EnglandFebruary 24th, 2026

-

Cheryle St. Onge: Calling the Birds HomeFebruary 23rd, 2026

-

Matthew Finley: An Impossibly Normal LifeFebruary 22nd, 2026

-

In Conversation with Louis Jay: Marrakech Face to FaceFebruary 15th, 2026