Photographers on Photographers: Congyu Liu in Conversation with Vân-Nhi Nguyễn

The first time I encountered Vân-Nhi Nguyễn’s work was while I was applying to several photography awards. As I looked through past recipients of the V&A Foundation Prize and the Aperture Portfolio Prize, her images immediately stood out. There was a quiet strength in the way each frame was composed — a sense of care, reflection, and tenderness that felt both personal and collective.

Her project As You Grow Older stayed with me long after that first viewing. The work’s reflection on history, the act of reconstruction, and its nuanced exploration of identity resonated deeply with me. As someone who also works with themes of historical memory, cultural inheritance, and the complexities of diasporic identity, I felt a strong connection to the ideas Nguyễn explores. Her images sparked a desire in me to better understand her approach — how she weaves personal and collective histories into a visual language that feels both precise and poetic.

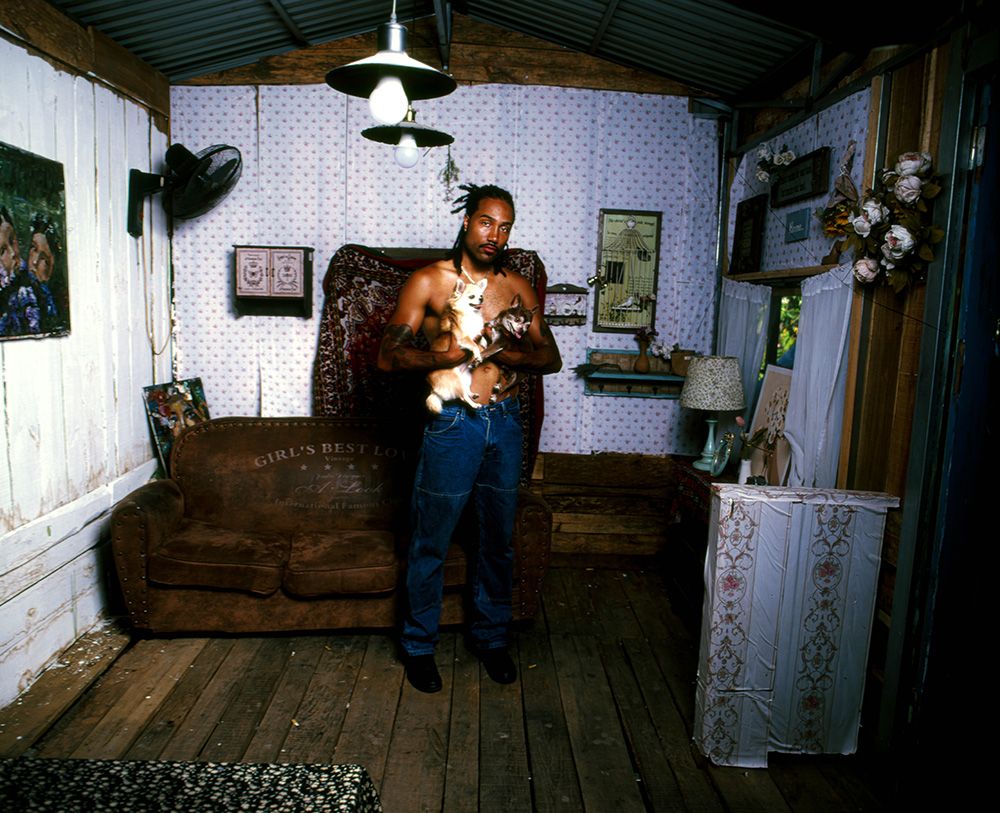

Vân-Nhi Nguyễn lives and works in Hà Nội, Việt Nam. Nguyễn’s practice thoughtfully examines contemporary landscapes and how it is anchored in memories. Through staged, idealistic domestic pictures, and collages made from both stock images and her own photographs, Nguyễn uses photography to lay bare these connections – she looks into ways that she can create a world parallel to the physical structures of the current non-westernized world, and how it can become emblematic of unfulfilled aspirations and unrealized potentials due to unresolved historiography. Nguyễn draws from a range of disciplines, borrowing methodologies from documentary, performances, and traditional fine arts. Within each work, Nguyen creates highly considered, layered, sculptural photography through the process of image making, collecting, which are offset by conditions for speculations, and improvisation.

Nguyễn has been presented at Objectif Centre for Photography & Film, Hong Kong International Photography Festival, Peckham Copeland, Fotomuseum Winterthur, Matca Space for Photography, amongst others. She has also received funding from the likes of Aperture Foundation, Pro Helvetia, V&A Museum, PhMuseum, to name a few. Her work has been published in various publications such as Aperture magazine, It’s Nice That, British Journal of Photography, Le Monde, etc.

Instagram: https://www.instagram.com/vnnhi/

Congyu Liu: What initially led you to explore photography as a medium?

Vân-Nhi Nguyễn: I think that photography to me, it came quite naturally I started just as like I when I was in high school in Vietnam we have like a photography club and I was like I was in high school and I just figured out that I’m not too good at anything at all so I might as well just join like a photography club for like shits and giggles and then it transformed like going to college but then and then dipping into like different majors so got into a lot so I got introduced to a lot of like art forms but I always find myself to really just come back to photography so like I was in college and I was do like I don’t know like stuff and that still there’s still like that aspect of photography always peeking through but I’ve never really paid attention to it until like I after college I moved back home and I started like going through a lot of like photos that my mom my mom had like a box of like family photos and it’s like a huge box sorry and I would like go through it every day just to see what happened previously, at least.

What is the history of this family? Because to me, even though I’m a person and I’m my mom’s daughter, there’s a lot of things in my family that I don’t know. And I feel like right now, I’m still trying to figure out what what that kind of history is and how this my family is a kind of like witness of that history, you know, because the Vietnamese history, it’s so it’s quite so brutalized and there’s not much.

Well, you know, it’s like, It has so many narratives, there’s like outside narratives and then there’s narratives in the north and then narratives in the south. And so trying to find what happened through the story of the people that lived through it, I guess. But yeah, I think I just like it really started with like a random box of family photos.

In the statement for your project Mother Dearest, you wrote: “photography is examined by looking at its connection with one’s own and the mass.” I resonate with that deeply — could you elaborate on what this means to you?

So I’ve been reading a lot, trying to figure out how to start this new project. I came across the idea of prosthetic memory, which is a term coined by Alison Landsberg. She talks about how the media we consume—especially now, when we’re constantly exposed to so much—can become part of our own memory. Even if those memories aren’t ours, we absorb them and start to think of them as part of ourselves.

That idea really struck me. As a Vietnamese person, I was thinking about the period after Đổi Mới, when Vietnam opened its doors to international trade and media. A lot of things changed. People began consuming new types of media, and I think that, in some ways, they started to imagine new identities for themselves through those images and stories. Maybe it was a kind of escape.

I started thinking about how that kind of identity-shaping feels like a form of acting. Like, you perform a version of yourself in front of others. But to them, that version isn’t acting—it’s just who you are. So I started questioning, if acting and being are so closely connected, then what are we actually trying to become?

That made me think about images. An image doesn’t really have meaning until someone gives it meaning. So I began making these very rigid, very staged photographs. When you look at them, you might not know what’s going on until I tell you. But I thought that was a really interesting way to talk about performance—something we’ve been doing all along.

Alongside the photographs, I’ve also been working with collage. For me, collage is like a visual language. It stitches together different things, and expands the surface of the image. That surface becomes a kind of refugium—a place where different people, times, and experiences can coexist.

A lot of the materials come from older work, especially As You Grow Older<, and from my photographic archive, mostly from my mom. I started creating this surface where people who have passed away, or people who are no longer in touch—maybe due to conflict or distance—can come together again. Sometimes it’s over small things, like someone being angry that you married the wrong person. But there’s still a desire to reconnect. So in this collage space, I imagine that kind of reunion—a space where coexistence is possible again.

I’ve read many interviews about your work to avoid repeating questions you’ve already answered — but I’m curious, do you see your work leaning more toward documentary or staged photography?

I actually don’t know because when I work I don’t really categorize myself as a documentary photographer. Or a visual artist or whatever, use it as a kind of thing which happens to be photography. And sometimes I would just, sometimes for the sake of like saying, for the sake of like having like a, having like a, like a title within it, I would say it’s documentary because there’s, within documentary there’s a little bit of a leeway for you to a range of something within the image surface.

I’d also love to ask: what role does staging play in your work? And how do you view the function of staged photography in relation to historical narrative?

Yeah, um, to me, I think I had to rethink the role of performance in my images. I started using staging—almost like theater—as a way to highlight a kind of regality within domestic spaces. That’s something we don’t often see when we talk about Vietnamese history. You rarely see what people were actually doing during the war—who they were falling in love with, what they were thinking, or what kind of small, daily activities they were still doing.

So when I began staging and performing in front of the camera, it became a way for me to bring those unseen layers to the surface. That act, to me, speaks more honestly about what remains hidden in Vietnam’s collective memory.

I feel like when people think of Vietnam, they only see the surface: the war, the violence, the devastation. It’s always the same narrative—Americans came, raped the women, killed the men, flattened the country. That version of history is brutal and overwhelming. So for me, staging became a way to reclaim something more personal. I wanted to make images that reflected what my family might have been doing at that time.

A lot of the scenes I stage are based on photos from my family archive, or even colonial images I’ve found online—where people are heavily posed and categorized. Those kinds of images tried to define who we were. So, by re-staging, I’m reclaiming the right to define myself and my history on my own terms.

But I also try not to over-intellectualize the staging part. Every time I go too deep into explaining it, it starts to feel like I’m speaking on behalf of others—and I really don’t want to do that. I just want to create images that I want to see, because they’re so absent. I rarely come across photos that show everyday Vietnamese life from those periods. So staging, for me, is a way to fill in those blanks. It helps me imagine more than what I’m told, or what limited images already exists.

I read that you often work with friends, family, or non-professional models — something I also love to do. Do you usually have conversations or prep sessions with them beforehand, or is there more improvisation on set?

A lot of the time, the images are quite planned. For some of them—especially in terms of production—it can take a few months just to figure out what I want to do in a space, and who I want to occupy that space.

The first step is always finding a room or location that I really connect with. That part usually takes the longest, because it involves a lot of scouting. I’m often looking for spaces that remind me of my childhood—places that look like the houses I lived in, or like the ones in the photos my mom took. Sometimes it’s about recreating the feeling of a road trip, or a small motel we used to stop at when I was traveling with my parents. It’s not just the architecture, but the small objects too—things that give a sense of care or belonging. I sometimes take those same objects and bring them into my current images.

So the background, the rooms, the little objects around the space—those are always the hardest to find, and they usually take the most time. But once I fall in love with the space, the image tends to come together very quickly.

When I’m finally in the space, I can usually tell right away who I think fits there. Most of the time, it’s my friends. I tend to photograph the same people again and again, because I love seeing the small ways they change over time—how they perform differently in each image. It feels like building a personal archive, like the kind you find in a family home.

So yeah, some images take two months to come together, some take two weeks. It really varies. I can do all the planning, but in the end, it always kind of arrives on its own. And I just think, oh—nice.

When you exhibited these photographs in Vietnam, I’m curious — how did the audience respond? Was it different from the reactions you received when showing your work in other countries, particularly considering language and cultural context?

That’s a really sensitive question—at least within the Vietnamese context. I’ll share this candidly: my work has been subject to censorship in Vietnam. I’ve gone through several rounds of appeals to get permission to show certain projects, even in small, private settings. But each time, the request was denied. Most recently, I submitted another appeal and was rejected again.

It’s been difficult to exhibit my work in Vietnam. So far, I’ve only shown one image publicly. The rest have been considered inappropriate, though the reasons are often vague. Sometimes I receive no clear explanation—just that the work doesn’t align with cultural expectations or “doesn’t represent us as a people.” But I’m not trying to represent an entire culture; I’m just trying to recreate images and things that I want to see.

This kind of challenge is something many Vietnamese artists face. It pushes us to look outward—toward international platforms, funding opportunities, and audiences who might be more open to the work. Despite these limitations, I think many of us remain motivated to keep creating, even if the visibility comes from beyond our home country.

I’ve had the opportunity to show my work internationally, but sometimes I feel like the audience isn’t fully connecting with the deeper context of the images. While the visual form I use may be familiar—especially within the aesthetics of American or Western photography—the story itself is not.

Even among diasporic Vietnamese communities, the narratives in my work often challenge what people think they know. These are stories that aren’t commonly told, and sometimes they go against more dominant or accepted versions of history.

That’s why it’s so important for me to exhibit my work in Vietnam—because I want the images to be seen in the place where these stories are rooted. I want the work to appear as I envision it: in ways that may feel bold or unconventional, but that I believe could expand how photography is perceived.

In Vietnam, photography is often seen through the lens of journalism or commercial beauty. I hope my work can offer another perspective—one that opens up new conversations around history, identity, and representation.

In an interview with PHMuseum, you mentioned how the colonial gaze in Western photography often objectified women, and that your work seeks to reconstruct those images. What do you think is the most meaningful part of this act of reconstruction?

I think that the most important part is the fact that I’m able to see what I want to see. And I feel like that is really important in any sort of way, which is being able to use your camera to speak the language that you want to speak, which I feel like it is not an easy language to speak because it’s so easy to assimilate with other languages that people have already Claim for themselves and so for me being able to just do anything and being able to just see what I want to see and Have an image look the way that I want it to look without like How do I say this without like the influence of Like a the influence of buying which is quite important to me.

So there’s no desire to commodify anything within that image. And I feel like that is very important within an image. Each images that I make, there’s no desire to commodify, but only to speak a kind of, to only kind of space that I want to be.

Are there any new projects you’re currently working on that you’d like to share with us?

I’m just working on the Mother Dearest thing. It’s actually still in progress. I’m trying to and then I’m trying to break into more installation and how I can incorporate photography in it, which is more of like a new school photography thing, and I feel like it’s nice to experiment, which is very important to experiment.

Congyu (Zoe) Liu, born in Beijing, China 1999, is an interdisciplinary artist who uses photography, film and video installation to explore the themes of female visibility and the Asian diaspora’s generational traumas and loss. She received a Bachelor of Arts degree from the University of Melbourne and a Master of Fine Arts degree in photography at the California Institute of the Arts. She is the 2025 Colorado Photographic Arts Center / Month of Photography Denver Equity Scholarship Winner and 2024 Now Trending: 8th Annual Alpay Scholarship Award winner. Congyu has recently exhibited her work in California Brand Library & Art Center, Palos Verdes Art Center, Santa Clarita City Hall, Good Mother Gallery, The Winchester Gallery (British).

Instagram: https://www.instagram.com/uil__eoz/

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

Photographers on Photographers: Congyu Liu in Conversation with Vân-Nhi NguyễnDecember 8th, 2025

-

Photographers on Photographers: Mehrdad Mirzaie in Conversation with Liz CohenSeptember 4th, 2025

-

Photographers on Photographers: Elizabeth Hopkins in Conversation with Nicholas MuellnerAugust 21st, 2025

-

Photographers on Photographers: Cléo Sương Mai Richez in Conversation with Shala MillerAugust 20th, 2025

-

Photographers on Photographers: Emma Ressel in Conversation with Tanya MarcuseAugust 19th, 2025