Melanie Walker: The States Project: Colorado

It is fitting to start a feature of Colorado artists with Melanie Walker. As an Assistant Professor at the University of Colorado Boulder for over 20 years, she has instructed and inspired countless undergraduate and graduate students (including myself and another artist featured in the Colorado States Project, Laura Shill). Melanie’s long trajectory in the arts has always pushed the boundaries of the photographic medium and challenged the notion of exhibition spaces. Her photographic kites turn the sky into an open gallery. With her partner George Peters, they develop public art pieces that interact with light and wind using sustainable, often recycled materials. In the interview below, I talk with Melanie about her long term project Nomadic Dreamer, the influence of her father Todd Walker, and her tools to stay inspired.

Melanie Walker has been a practicing artist for over 40 years. Her expertise is in the area of alternative photographic processes, analog, digital, and mixed media as well as large-scale photographic installations and more recently, public art. She attended San Francisco State University for a Bachelor’s degree in Art (1972) and Florida State University for an MFA (1975). She has received a number of awards including an NEA Visual Arts Fellowship, Colorado Council on the Arts Fellowship, and an Aaron Siskind Award. She taught at a number of universities including San Francisco State University, SUNY Albany, Alfred University, and the University of Kentucky, Lexington. She currently teaches in the Media Arts Area at the University of Colorado Boulder and has work in more than 80 collections including LACMA, Center for Creative Photography, Princeton Art Museum, and San Francisco Museum of Art.

I am interested in creating objects, atmospheres, experiences and memories. The underlying motivation in all of my work has to do with expanding boundaries, pre-conceptions, norms and expectations; the common thread being issues related to waste, excess, over-population and climate change. Connected by metaphor, place and association, disparate images are woven together as are life experiences in dreams. Wandering through memory, the body, mind and world are synchronized into a rhythm of thought, like a chord…walking and falling… Through my work I attempt to create a place where viewers can enter using their own experiences with the hope that viewers will look at themselves.

You have a long career as an artist. How did you get started in photography?

In a certain way, I feel like I was born into it. My grandfather taught my father a bit about photography before he passed away when my father was 14. My father, Todd Walker, had to go to work to help support his mother and sister. He was self-taught in photography and worked in the medium for 60 years.

When I was about five or six, I remember being really surprised to learn that not everybody’s father made pictures. I thought it was a given that all families were immersed in photography the way we were. My father worked on ad campaigns for General Motors and other notable clients. Frequently my sister and I posed as daughters in fictional family scenarios for Chevy advertisements. I grew up around some of the most amazing photographers of the 20th century that joined us for dinner, or worked on projects with my father…this was in the 60’s and 70’s before photography had been accepted as an art form.

I started taking photography seriously in high school. I applied to San Francisco State University, where I graduated in 1972. I moved to Florida and got my Masters at FSU and started teaching two weeks after my 25th birthday. Betty Hahn, Bea Nettles, Eileen Cowin and others who were investigating the malleability of the medium influenced a lot of the work I was doing in graduate school along with outsider and folk art. I was doing a lot of soft sculpture and interactive installation work in the early 1970’s.

After graduate school, I had to figure out how to make my work along with surviving. I moved around teaching at various universities. When I was adjunct faculty at San Francisco State I was strongly influenced by sound and installation artists in the Bay Area. I felt like I was getting at something that resonated intuitively by making immersive installations. I was born legally blind in my left eye, so I have constant double vision. Based on my perceptions, when one sense is compromised, other senses are heightened, so I focused on creating immersive environments that were tactile and incorporated sound.

The series Nomadic Dreamer has been a long-term, ongoing project. How did it start and how has it evolved over the decades?

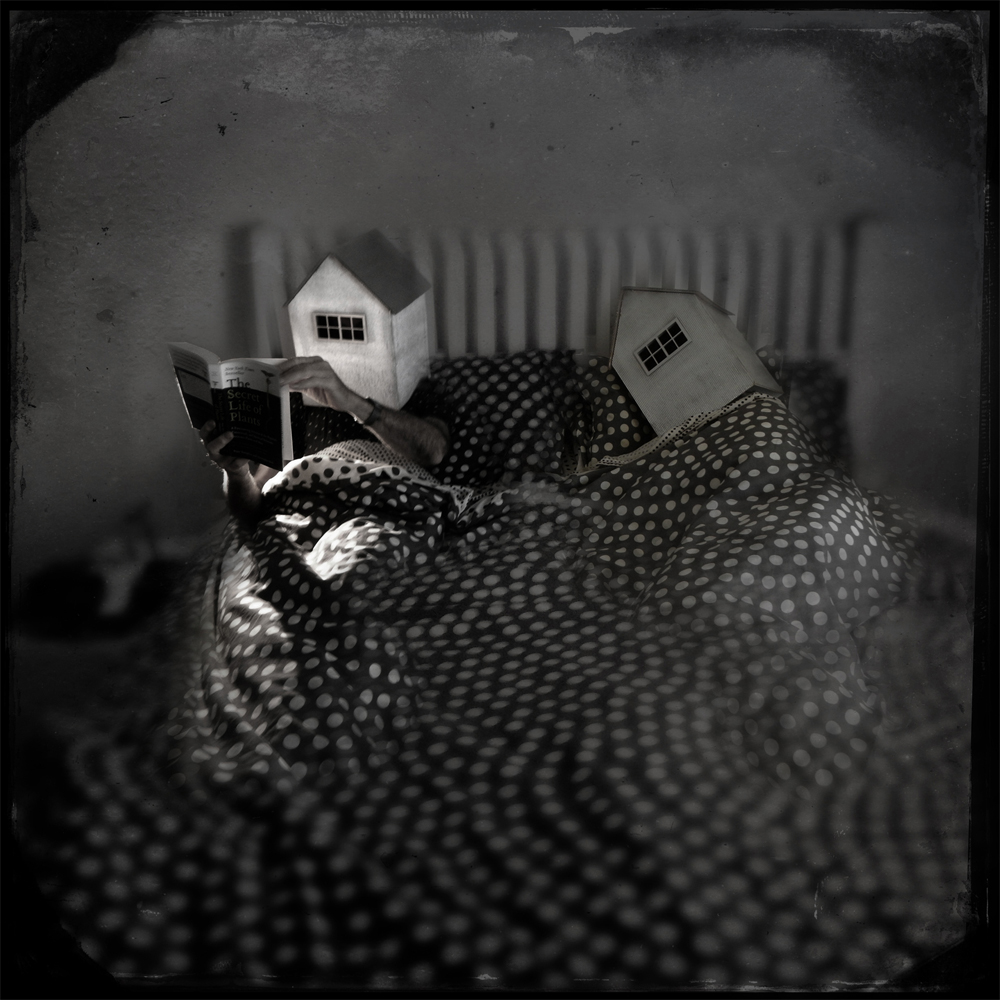

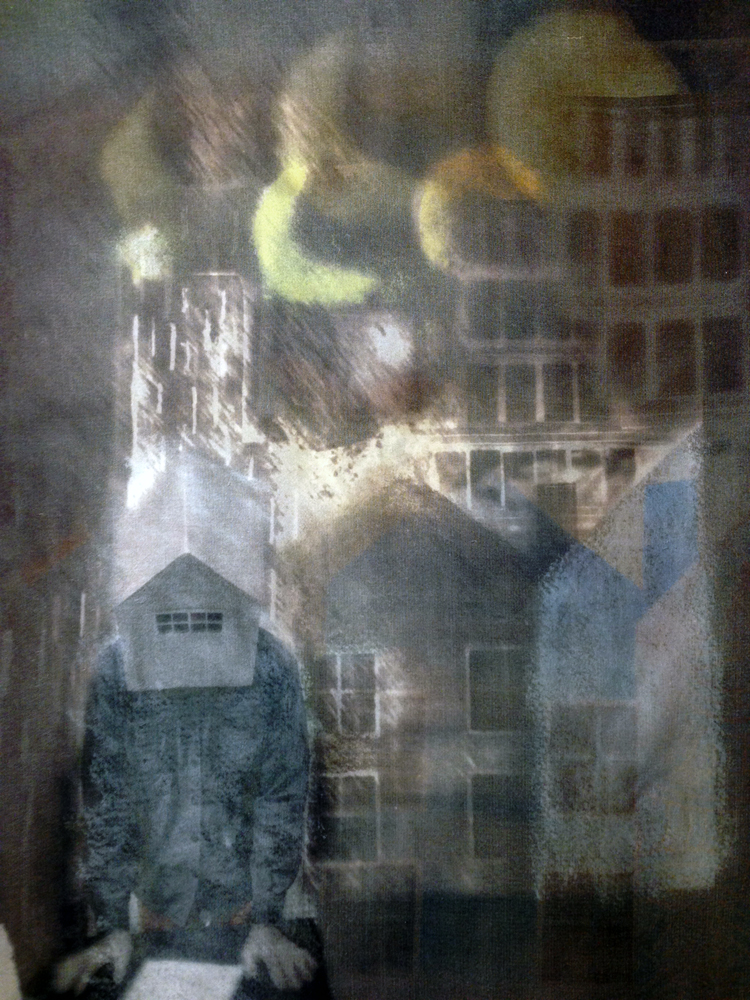

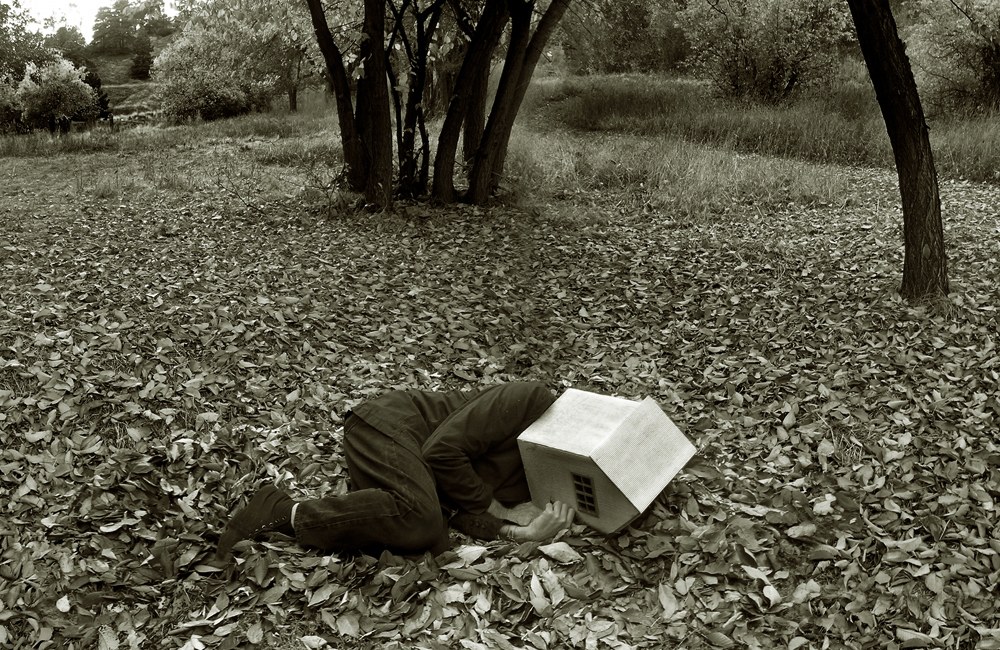

This project started in the early 80’s when I was invited to use the 20×24 Polaroid camera by Friends of Photography in Carmel. I had 60 pieces of color material to work with, and there would be an exhibition at Friends of Photography with the resulting work. I immediately had a panic attack and got deathly ill. This was an incredible opportunity but it could also be public humiliation. Also, I had never worked with color materials. While I was recovering, I had a dream about a person with a house for a head. I was a single woman at that point trying to figure out what being head of the house meant, being alone, and not having kids. This house became a personal narrative and a fictional family – which related back to the advertising work that I had been a part of.

I continually cycle through Nomadic Dreamer/Househead Chronicles returning to it as culturally we face different issues so the life of the project ebbs and flows. The project started in the 80’s when homelessness was a widespread phenomenon in San Francisco. Now that we are facing the refugee situation – climate refugees, political refugees – the strife that is going on, I find that I return to it once again to approach it in a different way. Another motivation for the return has to do with being the last in my immediate family.

What is the most recent interpretation of Nomadic Dreamer?

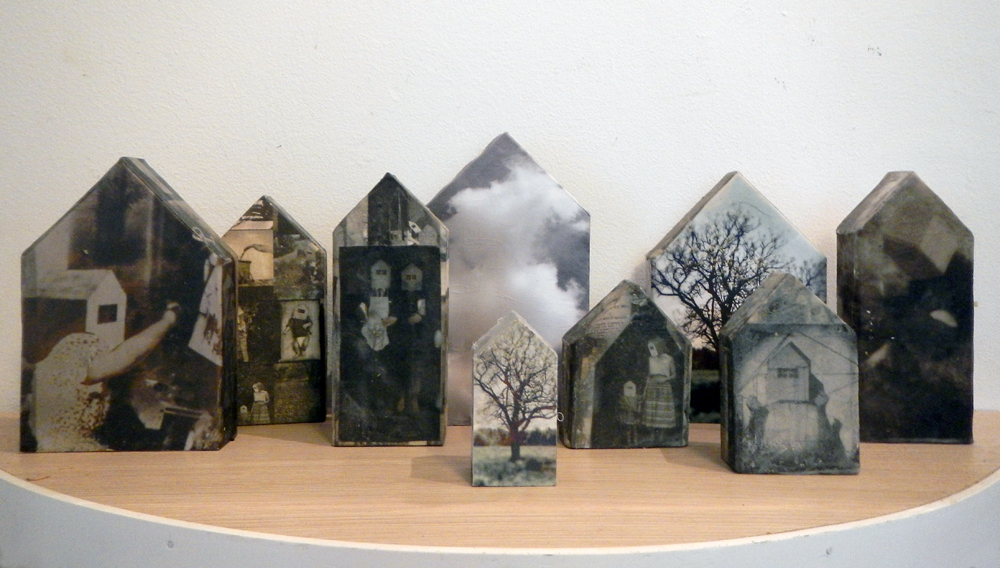

The most recent is the installation using shadows and silk. This project has never been one thing. It cycles through materials: some are prints, some are sculptural, some are puppets, some are installation.

What I’m trying to address with the house heads has to do with common ground and a sense of longing, and a need to be connected, to be a part of a family or a community and trying to convey the idea that we are all connected. The use of puppetry and installations engage a sense of interactivity.

A lot of my practice with the installation work tries to create an ephemeral, ethereal kind of space. I’m really interested in transparency and layering…it has to do with my double vision. One of my goals in life is to see in 3D. It’s kind of funny that I create 3D spaces, and that transparency, that layering, that ephemeral sense, gets to the root of how I experience the world all the time…I don’t know what is real…or I question what is real.

What projects are you currently developing?

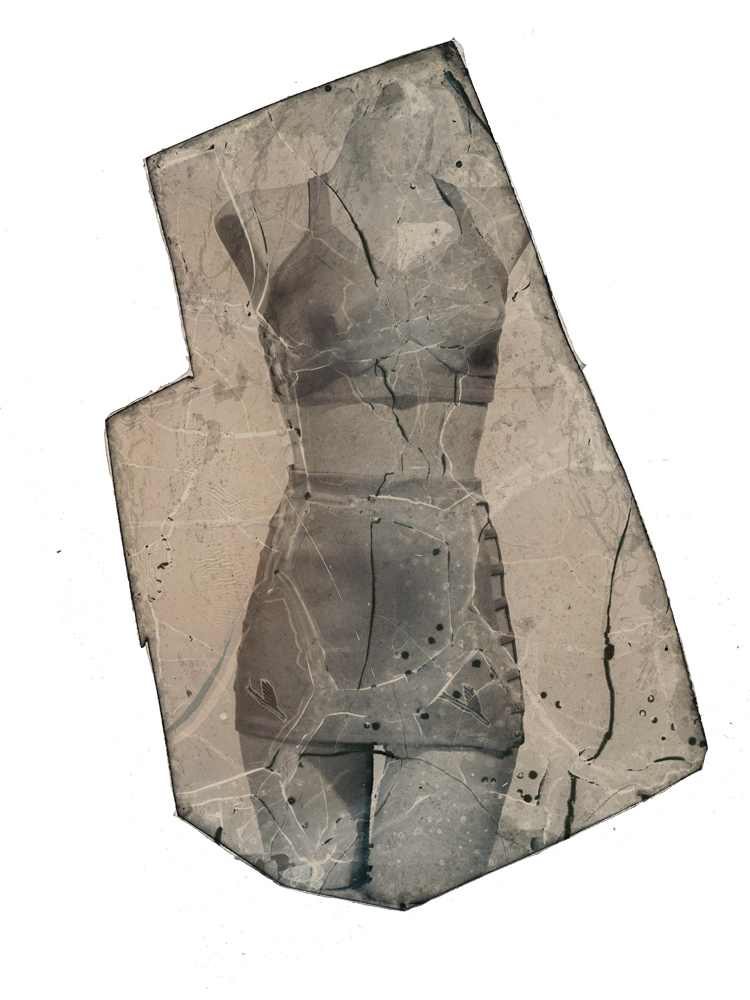

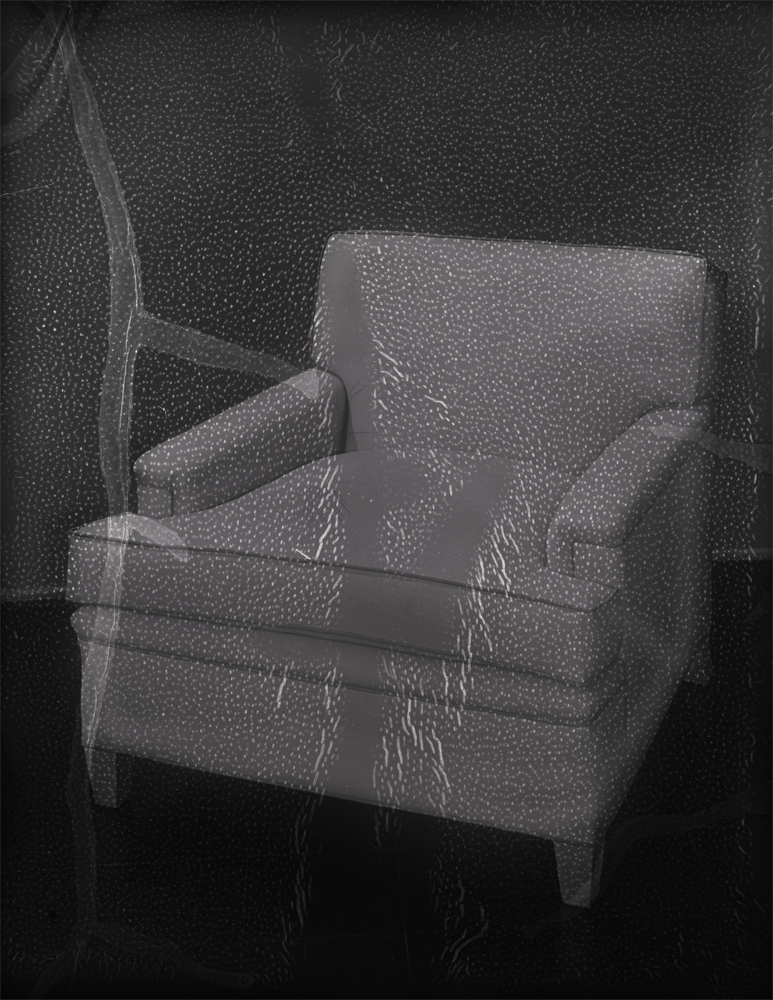

Over the last 20 years, I’ve been responsible for my father’s archives. I found a whole batch of negatives that he did for quick turnaround advertising. The negatives are completely compromised, the emulsion is barely sticking to the base…I’ve been scanning a lot of these negatives, making prints on very ephemeral materials, doing transfers on surfaces like mica, silk, platinum palladium prints with thin paper. I’m working towards an exhibition at Tilt Gallery in Scottsdale in April. We often think of images as something fixed or permanent. I’m very interested in these negatives of my father, revealing them in their fragile state. They have been subjected to extreme heat and moisture. The smell of the chemicals is notable. They are very interesting images because they were made for mass consumption.

Finally, what are three things that you listening to or reading that feeds your practice?

Rebecca Solnit is always a huge inspiration to me. I always gravitate towards her writing. A Field Guide to Getting Lost and Wanderlust are some of my favorite books. I also listen to Krista Tippet’s On Being…I’m drawn to the spirit that she seems able to conjure up with the line of questioning on the people she interviews. I usually don’t have a lot of stimulus in the studio so I can listen to my own thoughts.

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

Laura Shill: The States Project: ColoradoDecember 24th, 2017

-

Abbey Hepner: The States Project: ColoradoDecember 23rd, 2017

-

Teri Fullerton: The States Project: ColoradoDecember 22nd, 2017

-

Heather Oelklaus: The States Project: ColoradoDecember 21st, 2017

-

Ashlae Shepler: The States Project: ColoradoDecember 20th, 2017