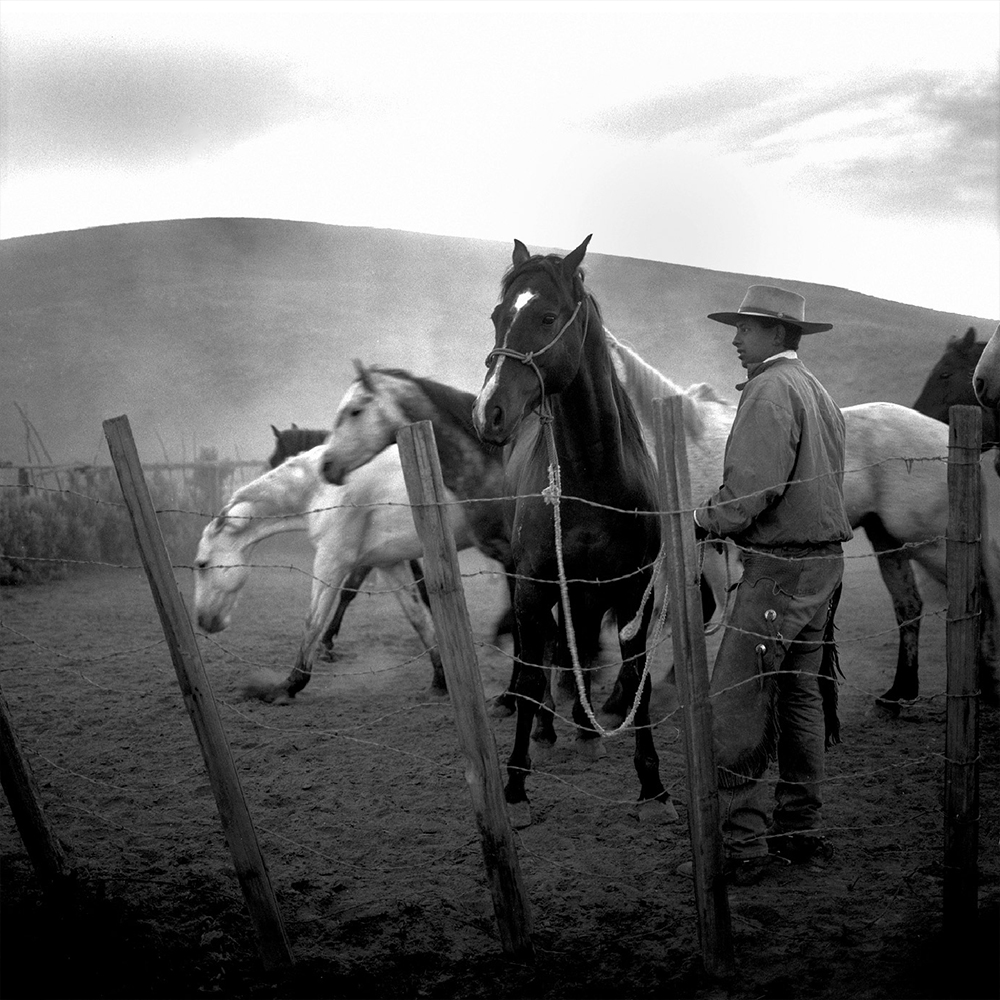

Adam Jahiel: The States Project: Wyoming

Adam Jahiel is an internationally recognized photographer who lives and works in the American West. Mostly known for his photography of the American Cowboy, his photography has taken him all over the world. His poetic and dynamic images have been exhibited and published across the globe. In 1996, he became the first living photographer to have a one-man show at the Buffalo Bill Historical Center, in Cody, Wyoming. His photographs are in the collections of the Nevada Art Museum in Reno, the Art Institute of Chicago, the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston, as well as private and corporate collections. Adam has had a varied professional career. He has worked for the motion picture industry, and adventure projects, most notably as the photographer for the landmark French-American 1987 Titanic expedition. His work has appeared in most major U.S. publications, including Time, Newsweek, The New York Times, National Geographic, Smithsonian and countless others.

Thank you for taking the time to speak with me Adam. You have quite a long history working as a photographer, notably as the photographer for the 1987 French-American Titanic expedition. How did you become interested in photography?

My father was a very talented photographer. He taught me how to use a camera, and how to develop and print in the darkroom. He was very dedicated to the craft for a number of years, as an enthusiast, not a professional. He was a film (movie) scholar, and so I grew up watching hundreds of films. I can’t imagine how many images I grew up seeing.

Interestingly enough, I originally wanted to be an oceanographer. Oceanography school introduced me to underwater photography, and that led me to photography school. Photography gave me a reason to travel, adventure, explore, and gain access to, study the human condition. Pretty soon I was photographing everywhere – except underwater. I loved diving so much that I decided to just enjoy the undersea world, without having to fuss with cameras, lenses and lighting. For me, that would be more work, than enjoyment.

Living in Wyoming seems to have a large impact on the work you make. Much is focused on Cowboy culture. What is your curiosity in showing the world that culture? Do you think it is a product of being embedded in it living in Wyoming?

I have always been fascinated by what I call “fringe” cultures. One ranch encounter, and I knew that I had to document this culture. How could I not?

These people represent one of the last authentic American subcultures, one that is disappearing at a rapid rate.

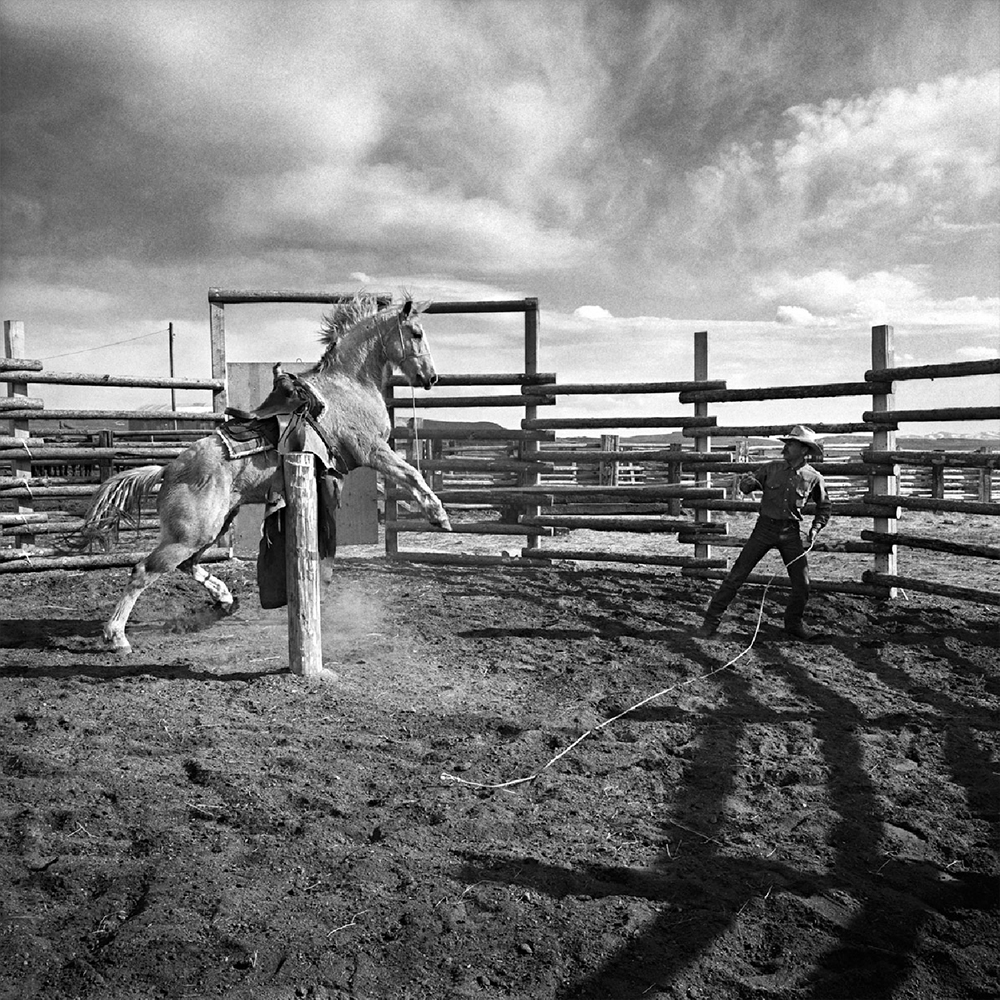

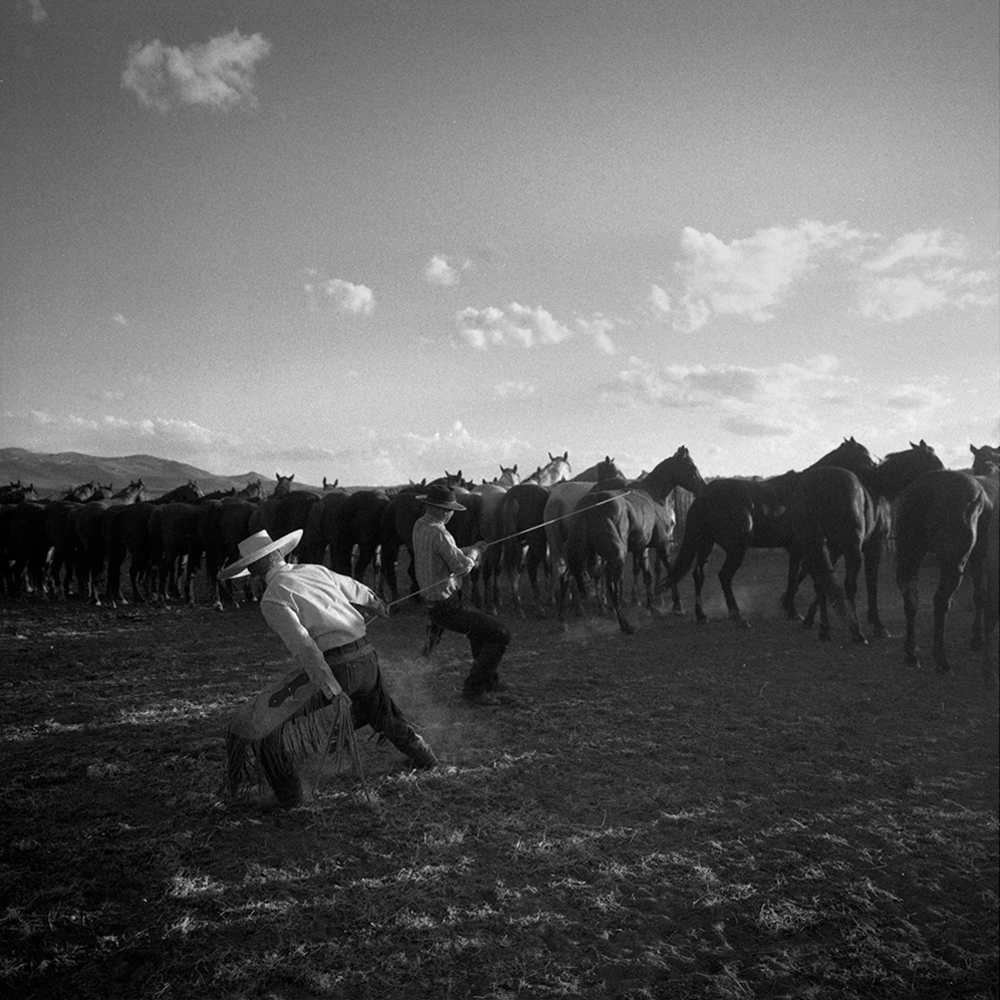

Cowboying as an art form is almost obsolete; still, the cowboys hang on, with a ferocious tenacity. Respect there doesn’t come from the trappings of modern life. Talent, knowledge and skill are valued above all else. And the cowboy tradition has its roots in the oldest of human conflicts: man against nature and man against himself.

I began photographing on ranches and cow-camps before I migrated to Wyoming. When I discovered Wyoming, it felt like home and still does. The writer Carlos Castaneda wrote about a ‘sense of place’. The Bighorn Mountains area gave me that “sense”. It still does. I worked on a photographic documentation of a large ranch near Sheridan. In doing so, I fell in love with the land, the light, and the people. I had stumbled into a place where I felt at home. I couldn’t leave all that behind. After 8 years in LA and California, it seemed like paradise. It still does (except those last two months of winter). Living in this Western culture encourages me to look and think about the West and cowboy culture. One cannot avoid it. It seeps into your soul. It gets under your skin and into your blood.

Cowboy culture, depending on where you happen to be, can be very similar and very different. Many aspects of the culture vary from one geographical area to the next. Nature dictates many of these differences. Land, weather, population, distances, economics, and tradition all factor in to these. At bottom, there is a commonality that I describe as a ‘spirit’.

It is a world without schedules and hours. The work is done when the work is done. There is little dependence on modern technology. These people get their hands dirty. They are both literally and figuratively down to earth.

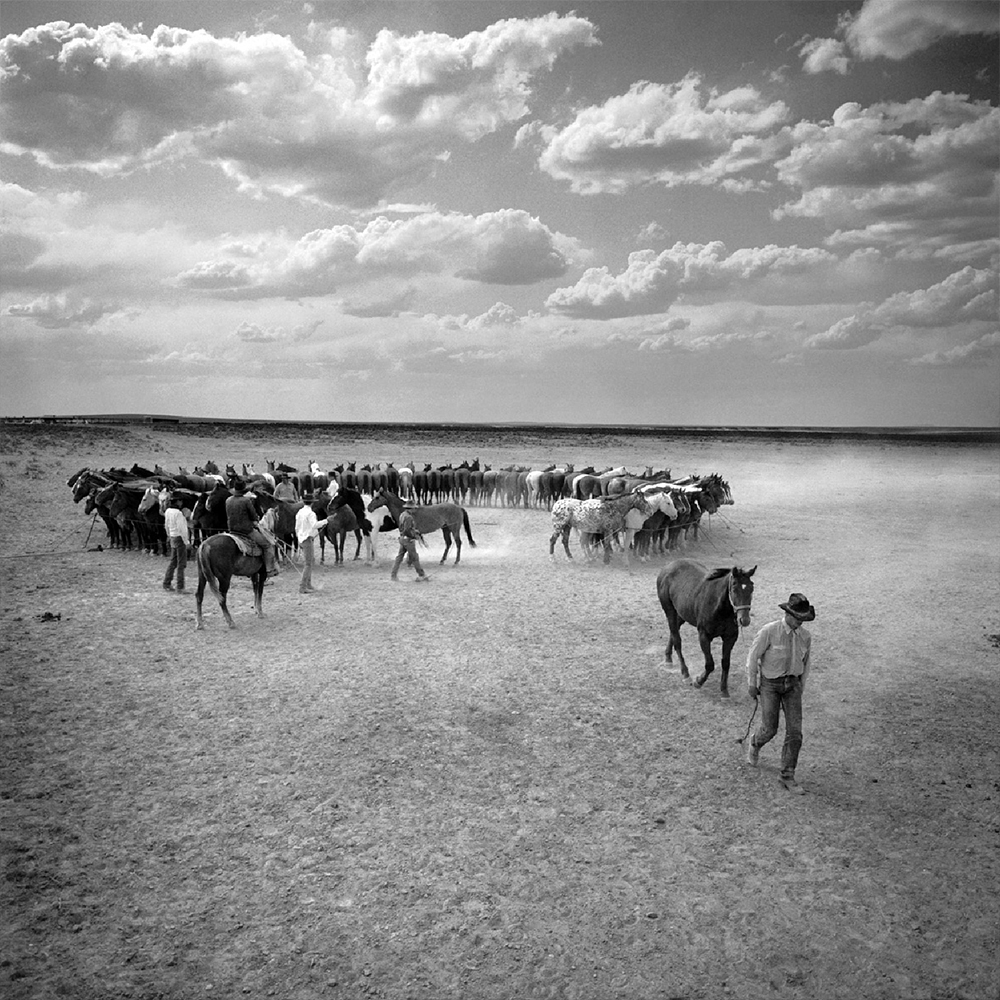

For many years, I concentrated on the cowboys in the Great Basin area of the US, especially the Nevada Buckaroo. There you had huge ranches in the high desert, cowboys that went out on the “wagon” in the Spring and camped out in the desert in their teepees moving from one place to another as Spring turned to Summer, and as Summer turned to fall. The cow-camps they set up are often miles from the ranch headquarters, and in turn, the ranch headquarters may be hours and miles to the nearest town. The Buckaroo style of gear, dress and working, comes directly from the Spanish Vaqueros, that came out of Mexico and moved their way North in California to the Nevada, Oregon, Idaho areas we know as the Great Basin area.

In Wyoming, the ranches tend to be smaller, the towns are closer together, there are more roads, and the population is larger. These factors impact how the work is done. Here, ranching tends to have more familial and social aspects. Brandings, for instance, often consist of the cowboys on a given ranch, helped out by friends and neighbors that come and help out. At the end of the day, cowboys return to their homes, and not to a teepee in the desert.

As someone who is inspired by Western cinema, I am really drawn to the series The Last Cowboy. All of the images are extremely beautiful, playing off how many romanticize the American West. Can you tell us a little about that series? Why did you elect to use black and white film rather than color?

It’s complicated. I’m not sure I know the answer.

Everybody has his own measuring stick. To me, a great photograph is often a combination of several elements. Craftsmanship is one, especially with black & white, I think that technical excellence is important.

There is the visual aspect, where light, shape and form, and placement of elements within the frame combine to create an image that feels good to the viewer. And there is content, very important, without which, the photograph becomes merely a decoration. Finally, there

is the photograph’s ability to address some facet of humanity and the natural world.

You have to have something to say, and have the ability to say it.

I work in B&W and color, but I usually prefer B&W. To me, color often becomes too real, too literal. It seems like more of a recording that a statement or a question. B&W seems to have the ability to distill, creating the essence of the subject. I become more aware of the nuances of light and shadow, form, line, and shape.

There is a real romance to the American West, but I think that there are different kinds of ‘romance’. Most people only know the popular culture-Hollywood romance, which has been commercially exploited forever. For me, the real romance is powerful, nuanced, and hard for me to describe. It has to do with the physicality of the experience. You are in the middle of nowhere, horseback, totally in control, completely responsible for your actions. You watch the light change from before sunup until sundown. You feel every degree of temperature change, every puff of wind, every drop of rain, every ray of sunshine. You feel every muscle in your body, and that of the horse. Every step the horse takes is also your own. You are in the moment in every moment. You just are.

That is what I would like to convey through my images. I don’t always succeed.

The title suggests that cowboys don’t exist in modern society. Do you think anyone be a true cowboy in 2019? How would that be performed and look like compared to when the series was made?

Maybe a true cowboy is more of a state of mind than anything else. There are still real cowboys today, just not as many as there used to be. The “disappearing cowboy” is both a cliché, and a truth. It is happening, and it will happen. As society becomes increasingly mechanized, the more the cowboy icons disappear. Four wheelers have begun to replace horses, cell-phones are encroaching on solitude. Cowboys seem to get younger. Cowboying is rarely a full-time occupation. There are hardly any ‘career’ cowboys anymore. Fences and corrals that used to be made of trees are now factory-made metal panels. Baseball hats and T-shirts are often accepted dress. The tradition is slowly eroding.

Your Willow Creek Ranch series is similar in its construction of The Last Cowboys and another beautiful take on something that is extremely important to Wyoming history and culture, ranching. In Willow Creek Ranch, female figures begin to be shown. Was this a choice on your part or did the female role as a rancher evolve and change? Are gender roles changing as the number of ranches dwindles?

As the number and size of the ranches dwindle, females are more visible. They have always been an integral part of ranch life, and have always been indispensable, just not as visible as they are today. As ranches get smaller, more people have to take on different jobs. Traditionally, women have existed behind the scenes, whereas today, they often work alongside the men.

Both projects are a mix of portraiture, landscape and “action” type photography, creating a larger picture and insight into the lives of those pictured. Why did you elect to use so many methods of creation?

I have never consciously chosen one particular approach. My philosophy has always been that the subject dictates the approach. That subject usually dictates whether I shoot B&W or color, use large format or small format, use film or digital, shoot with natural light or studio lights. I try and use the right tool for the right job.

If I see something that I react to, I’m not very analytical. I just react and shoot. Maybe in the best Western movie tradition, I “shoot first and ask questions later”.

You also host workshops at the actual Willow Creek Ranch, which is a unique opportunity for those that have never experienced ranching culture on such an intimate level, such as myself. The images your students create a beautiful. Can you tell us a little about that workshop and your students?

My Willow Creek Photo Workshops, are one of the most enjoyable aspects of my photographic life right now. The Willow Creek Ranch At The Hole-In-The-Wall is one of the most beautiful places on the planet. It is 57,000 acre cattle and horse ranch located West of Kaycee, WY. It is comprised of flat open range, canyons, and the 350’ tall, 70 mile long red sandstone wall that is one of the most impressive features in the West.

Every year, I teach two week-long workshops, one in the Spring and the other in the Fall.

I keep the workshop group to no more than 8 participants. Much of the workshop is about looking and seeing light and how it affects the land, horses, cattle and cowboys, so no particular skill level is required. I have taught beginners and professionals. We all learn. We shoot digital, so we can shoot and look at the results within a few hours. We follow the cowboys as they go about their work, and we end up seeing a little bit of everything the ranch has to offer. This is not one of those workshops where models are hired and setups are organized so everybody can go home with a canned photograph. We do a slide-show at the end of each workshop and amazingly, every photographer produces different images.

Usually half of my students are returning participants. Some have attended 5,6,7 times.

The workshop information along with links to the slide show, are on my website; adamjahiel.com .

Who are some of your favorite photographer or ones that inspire you and your practice?

I could write a book on my favorite photographers.

I have always loved the images from the FSA (Farm Security Administration). That work has probably influenced mine more than any other photography. FSA photographers include Dorothea Lange, Marion Post Wolcott, Walker Evans, Jean Vachon, Arthur Rothstein, Russel Lee are some of my favorites.

Favorite photojournalists, Cartier Bresson, Marc Riboud, Ernst Haas, Mary Ellen Mark, Susan Meiselas.

Recently, I have fallen in love with the work of Vivian Maier, a previously unknown photographer that I would put on the top of my list. Her photographs seem almost too good to be true. Just amazing eye and craftsmanship. And her story, or the story of her photographs, is utterly fascinating. She has been the subject of several documentaries.

Finally, there are the great cinematographers, Roger Deakins, Lazlo Kovacs, Januz Kaminski, Gordon Willis, Vittorio Storaro, Vilmos Zsigmond, Greg Toland, Nestor Almendros, and many more.

I have learned from, and been influenced by these great cameramen.

Adam Jahiel June, 2019

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

Olga Fried: Intangible EncountersFebruary 18th, 2026

-

Anne McDonald: Self-PortraitsFebruary 17th, 2026

-

Richard Koenig: Field Notes: View from a Hotel WindowFebruary 13th, 2026

-

Beyond the Photograph: Editioning Photographic WorkJanuary 24th, 2026

-

Ben Alper: Rome: an accumulation of layers and juxtapositionsJanuary 23rd, 2026