Publisher’s Spotlight: Sming Sming Books

This month is all about books on Lenscratch. In order to understand the contemporary photo book landscape, we are interviewing and celebrating significant photography book publishers, large and small, who are elevating photographs on the page through design and unique presentation. We are so grateful for the time and energies these publishers have extended to share their perspectives, missions, and most importantly, their books.

Vivian Sming is an artist-publisher based in the Bay Area, who produces a wide range of artists’ books through her publishing studio Sming Sming Books. Formed in 2017, the studio experiments with books as art, discourse, exhibition, and archive, working in collaboration with artists whose works and ideas inform design, material, and printing choices. Sming is invested in creating books from practices that are challenging to represent on paper, and is committed to promoting critical discourse and advancing cultural equity through the format of publishing. She is the former Editor in Chief at Art Practical, co-founding editor of nonsensical, a journal of writing by visual artists, and is currently the Design Director at 826 Valencia. She holds an BA in Art from UCLA, an MFA from CalArts, and was a 2016–17 Fellow at Yerba Buena Center for the Arts. Sming Sming titles have been collected by over eighty libraries, museums, and universities, nation- and worldwide. Select books have been featured in aperture, Art in America, BOMB Magazine, Hyperallergic, and the New York Times. In 2018, Sming Sming Books received the Shannon Michael Cane Memorial Award from Printed Matter, Inc. and in 2020, the San Francisco Art Book Fair Publishing Grant. Past workshops and lectures have been held at ArtCenter, Asia Art Archive in America, California College of the Arts, Columbia University, UC Berkeley, and Vancouver Art Book Fair.

Today photographer and editor Erica Cheung interviews publisher/artist Vivian Sming.

Follow Sming Sming Books on Instagram: @smingsmingbooks

EC: What was the first book you published, and what did you learn from that experience?

VS: Before I started Sming Sming Books, I self-published a book titled Love Songs for Antarctica and co-founded and edited Nonsensical, a journal of writings by visual artists, with artists Páll Haukur and Alice Wang. I worked on a bunch of different publications in an editorial capacity and from those experiences, I learned a lot about the processes of producing a book.

The first year of Sming Sming Books—2017—there wasn’t just one book I started off with, but a group of four or five, including books by Kang Seung Lee, Indira Allegra, and Sable Elyse Smith—and then it just kept growing from there.

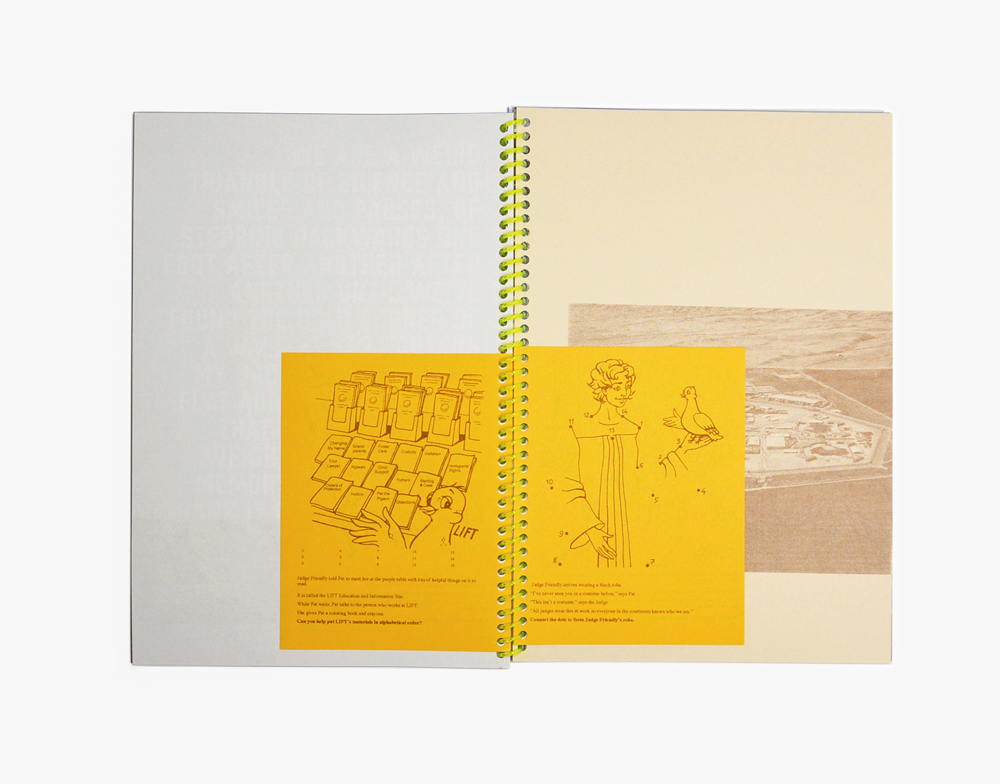

I would say that Sable Elyse Smith’s LANDSCAPES & PLAYGROUNDS really changed the direction for me. When I first started, I’d been thinking about books more as monographs, as a straightforward way of documenting a body of work. But Sable’s work is so sculptural and installation-based, which doesn’t necessarily translate onto paper in the same way that drawing or photography does. LANDSCAPES & PLAYGROUNDS was really one of the first books that moved my thinking in terms of what a book could really be. We really thought about and played with color, form, and material. I was just so excited by the result and the possibilities it opened about what an artist book could look like and what it could do.

EC: What is your mission as a publisher?

VS: I think of my mission as creating books that spark discourse. Living here in the Bay Area where real estate is so expensive and having space—let alone an artist-run space—feels out of reach, the book form clicked as a viable extension of discourse, as something that doesn’t require a lot of space and has longevity in that books can be passed around and down to different generations.

What’s important with Sming Sming Books is that there needs to be some sort of reason that each project is a book. With social media, blogs, and other online platforms, there are so many options for what publishing can look like—so for me, for something to live as a book, there has to be that intentionality.

The other part of my mission is to experiment with the book form. I don’t use templates; everything starts from scratch with the artist. The process really is about prioritizing the artist’s ideas first, and then arriving at a design and form to fit the artwork—down to the font choice! I’m interested in creating books that become an extension of the artwork.

EC: How big is your organization? Is it just you at Sming Sming Books?

VS: Yes, it’s just me! I’m the designer, editor, production manager, bookbinder, distributor, web order fulfiller—all in one! I do work with an assistant when I’m overwhelmed, and my partner-in-life has mailed out a lot of packages on my behalf. I also work with a variety of printers depending on what the artist needs.

EC: What are the difficulties that publishers face?

VS: Over the years and after trying different models, I’ve found that it’s really hard to make money off of books. The goal is to be sustainable, but even that is really difficult. Most independent art book publishers out there are juggling other kinds of work—producing books on commission, taking on design or print work, or something else entirely.

I think it was last year when I finally said, “I’m just going to come to terms with this: there’s just no money to be made.” I break even—but it’s kind of weird to say I break even because I don’t pay myself. (I have a full-time job.) Technically, I’m just owing myself.

I started my first year with $5,000 that I’ve been able to keep recycling to be able to support as many artists as possible. Some books do better than others, but all of this doesn’t really determine what’s ‘successful’ for me. I view a ‘successful’ book as: Was the relationship I had with my collaborator good? Did we have fun? Did we come to an exciting result that really feels like something that challenges the book form? For me, whether or not a book is ‘successful’ depends on these factors more than if anyone’s interested in the final product.

I don’t have the answer to how I’d make things work better. But shifting things to more of a profit-driven model might also mean sacrificing some of the choices I’ve made, like not using set templates or like choosing to work with a totally different printer every time. It would be so much easier to produce the same form over and over again, to strike a deal with a printer and just print in mass quantities—which would align with a profit-driven approach. That’s never been my goal, though. The goal has always been: is this book an accurate representation of the work itself?

So, maybe it’s that I’ve chosen the difficult path! But I would also love to see more opportunities for substantial financial support for publishers!

EC: Are there any publishing projects that have been particularly meaningful to you?

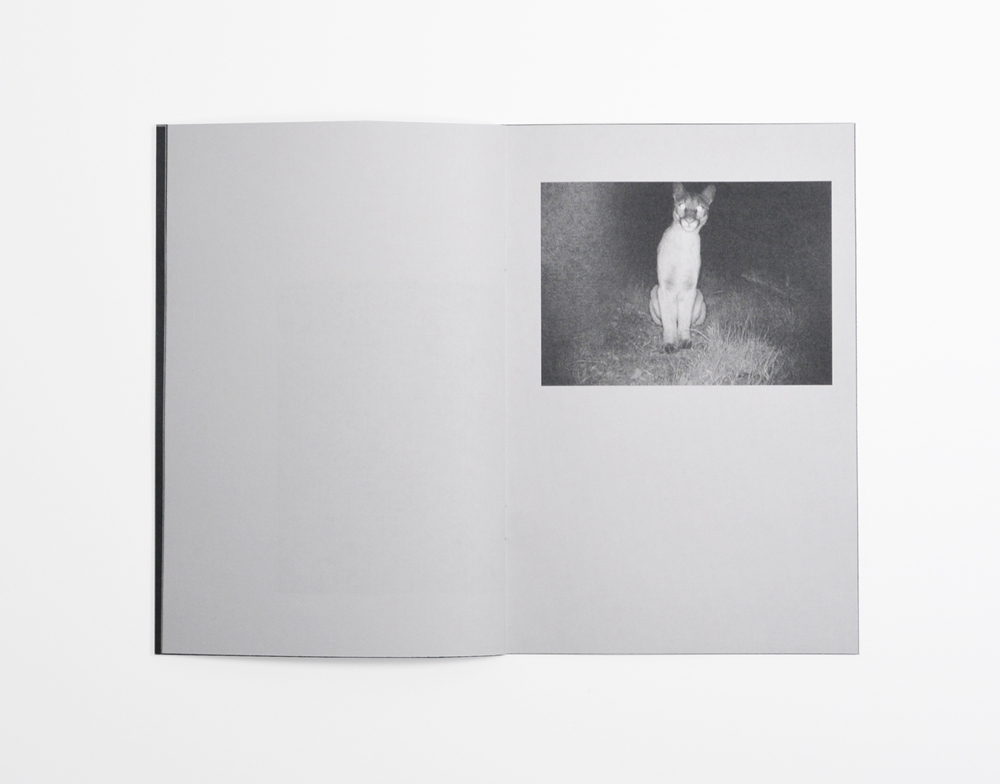

VS: Yes, absolutely! I should’ve mentioned NIGHT MOVES by Katharina Piereini earlier as one of the first books I worked on. Katharina is not a formal artist. She’s an incredible outdoorsperson, who has set up infrared motion-sensor trail cameras in her backyard. She shares footage from the cameras on her Instagram, @bergundwald, and I was particularly drawn to her photos of bobcats and mountain lions at night.

I like to point to this publication as one that expands what art is or what art can be. There would’ve been so many steps and barriers to show Katharina’s work in a traditional art space, but with the book format, it’s super accessible and there’s an immediacy to how the work is experienced. Most people, for instance, are taught how to read a book, but not many are taught how to read an exhibition, let alone how to interact within a gallery or an art space. We are taught early on that anything within a book has value, and it’s incredibly liberating not to be concerned about something being distinguished as “art” but just being experienced as such.

EC: What upcoming projects are you excited about?

VS: There are so many! I’m currently working on a tarot deck with Kenyatta A.C. Hinkle, which I’m really excited about. Kenyatta has been working on this project called The Evanesced for years, which consists of hundreds of drawings she’s created by channeling the presence of missing Black womxn. The drawings, which she calls “un-portraits,” are going to form the cards in the tarot deck. In some ways, it’s an artist book, but at the same time, , it’s this totally other form which can actively be engaged with.

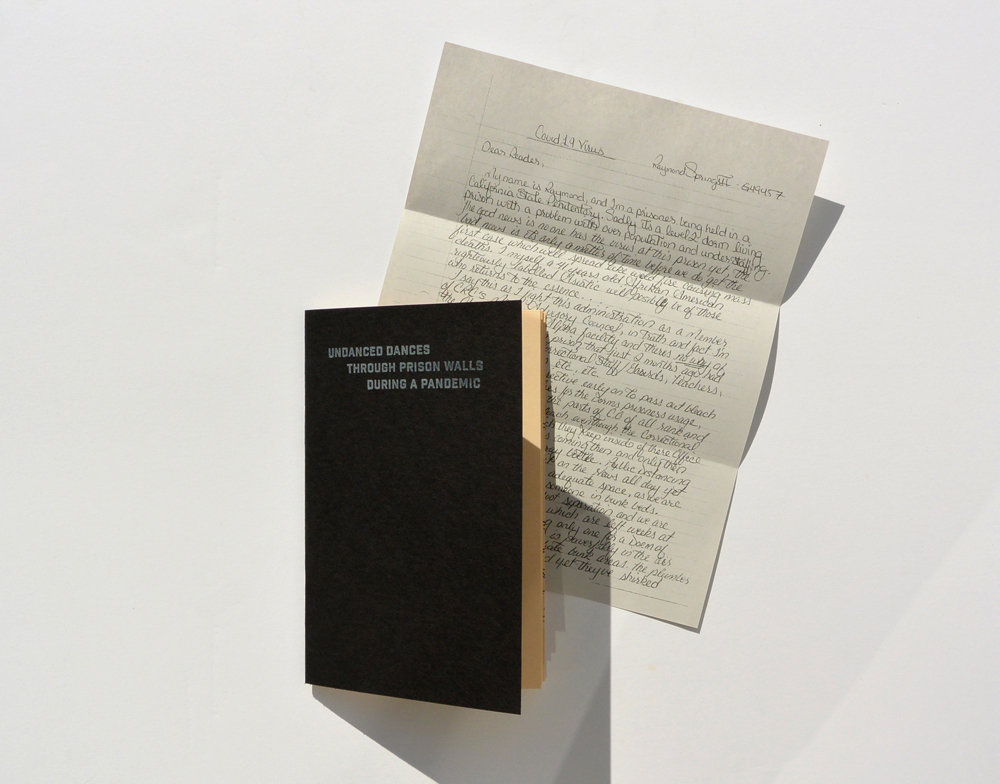

Suchi Branfman, ed., Undanced Dances Through Prison Walls During a Pandemic (Saratoga: Sming Sming Books, 2020)

EC: How many books do you publish a year, and how do you choose which projects to publish? Do you have a specific focus?

VS: It definitely varies. I’ve slowed down recently because of burnout from the pandemic, but there were some years when I was producing up to ten books a year.

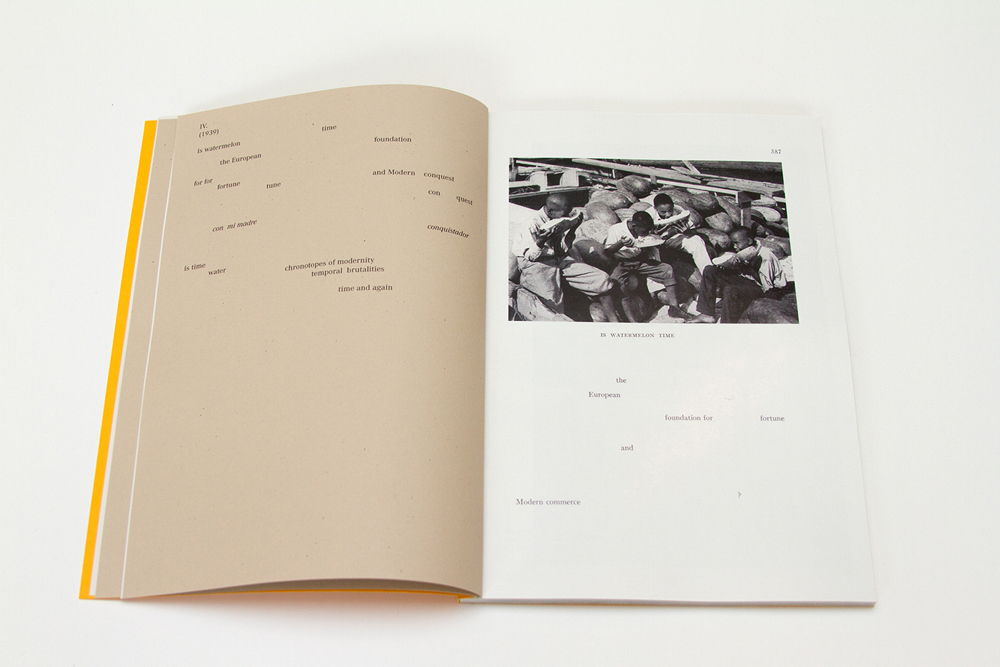

There are so many threads that I have in my own head, and the fun part about publishing is that I get to see those threads through. One of Sming Sming Books’ throughlines comes from my love of engaging practices that are challenging to represent or document. Another throughline is looking at writing that doesn’t really quite fit the typical literary genres—particularly by artists who are also writers. There’s also a throughline of centering folks who are using their practices in creative ways to dismantle white supremacy. I have an interest in animals and posthumanism, too, so there’s some of that in there as well. I just need to make more books—I’m sure more things will come about!

EC: How can an artist get their work in front of you? Does it all just start with an artist you admire and you strike up a conversation with them about how their ideas might be manifested in a book?

VS: It’s a combination of both. There were artists who, after I started publishing, would approach me with ideas. A lot of the books have been produced through those relationships. With the artists I approach, sometimes I reach out with a specific body of work in mind that I think might translate well into book form. Sometimes it’s more of a general interest, and that usually takes longer to develop because the concept for a book isn’t already there, so it takes time to get to the point where something feels right.

Artists that approach me usually have an idea in mind. I often don’t work with people who already have their design in place, or who already have a specific vision of producing a coffee table photobook. I’m very clear that that’s not what I do.

For me, it’s really about finding people who are a good fit in terms of being open to the form, open to the resourcefulness, open to a little bit of imperfection, and of course, open to collaboration. The books I’m producing are not necessarily highly polished; it’s all about transforming the humble material of paper into something as close to the artist’s vision as possible. I use a mutual trust agreement to establish my relationship with the artists I work with; it’s really a process of care.

EC: What is the typical timeline of a project, from the beginning to the finished product?

VS: I do not set deadlines for people—this is something I have outlined in the mutual trust agreement. Usually the artists I work with will have their own deadlines that they’d like to meet—sometimes it’s a show or program they want to have the book done in time for. Sometimes we’ll try to aim for an art book fair, but deadlines are not a pressure I’m interested in applying to people. I definitely acknowledge the time that the whole process takes. Most of the labor for a book is really on the artist’s end in terms of making the work itself and putting all of the pieces of their work together. Everything’s easy after that—design, editing, and whatever else needs to happen can all materialize pretty quickly. But it’s the artist’s work itself that can sometimes take years to make.

EC: How collaborative is the design process with the artist?

VS: The design process depends on what the artist needs the work to do. Some artists are more interested in distribution, whereas others would rather have the book go through more intensive methods in terms of the way that the book is made. There’s a balance and understanding of what each artist needs from their project.

The first step is usually me understanding the artist’s work to the extent where I feel like I can imagine what decisions an artist might make for themselves. Throughout the process, I check in with the artist and ask for permission a lot. Since I’m approaching their work as a fellow artist and not as a formally trained designer or editor, I’m not going to impose my own vision on top of their book. It’s really about finding the form for the work itself alongside the artist.

EC: How is the financial side of the project structured between publisher and artist? Does the artist contribute to production cost?

VS: When I initially started, I paid a small advance with royalties to the artist—which is a more traditional, literary model, in addition to covering all product costs. It ended up not really making sense for books that were smaller editions. Since then, I’ve tried a lot of different models.

Things got complicated when there were folks who wanted to publish with me, and they sometimes had a budget. Usually if someone has financially contributed to a portion of the book, I list them as a co-publisher because I feel like if anyone looks at a book, they’re going to assume that the listed publisher name is the funding entity—which isn’t always the case in practice. There are a lot of publishers who use a pay-to-play model, where they’ll say, “Yeah, I’ll publish your book if you raise X amount of money”—which I feel is not cool.

As of last year, I moved to a model where I start with a flat artist fee depending on the scale of the book. There are no royalties or anything like that; it’s just a flat fee and copies of the book. I pay for all of the production, and all of the labor.

There’s a talk that I did with Public Collectors, Coloured Publishing, and GenderFail called “Towards a Self Sustaining Publishing Model” where we get into finances. If you’re interested in more of the nitty gritty, I’d refer you to that. I break down my income and expenses from publishing there.

EC: Once you have the printed books, where do they go? What support do you give artists in terms of marketing or distribution?

VS: The books go out! I sell them through my online store, and back when we were doing art book fairs, I would sell them there. I’ve only gone to a few fairs online recently, and definitely miss in-person fairs.

Everything else is very organic in terms of press, and in terms of independent bookstores and libraries reaching out to carry or acquire certain titles. I have a full-time job, so I don’t always have the capacity to push for things like press or distribution. My energy predominantly goes into making books that I think really matter and hold their weight in history. Given this intentionality, I just kind of let the rest come. If people are interested, they’re interested, and I let that grow on its own rather than trying to do a bunch of outreach.

EC: I’m looking forward to seeing what else comes out through Sming Sming Books! Thank you so much for your thoughtfulness.

VS: Hopefully it wasn’t too much—I could easily go on and on about books!

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

Publisher’s Spotlight: Smog PressJanuary 3rd, 2024

-

Publisher’s Spotlight: Kult BooksNovember 10th, 2023

-

Publisher’s Spotlight: ‘cademy BooksJune 25th, 2023

-

Publisher’s Spotlight: Brown Owl PressDecember 10th, 2022

-

Publisher’s Spotlight: DOOKSSeptember 26th, 2022