Student Prize 2025: Top 25 to Watch

Every year, the Lenscratch Student Prize gives us an opportunity to celebrate and support the next generation of photographic artists. Hundreds of artists shared their work with us– powerful creative voices that make us truly excited about the future. Before we begin the celebration of our 7 winners tomorrow, we wanted to shine a light on 25 photographers that you should have (and keep) on your radar. Congratulations to all!

An enormous thank you to our jurors: Aline Smithson (Founder and Editor-in-Chief of Lenscratch, Educator and Artist), Daniel George (Submissions Editor of Lenscratch, Educator, and Artist), Linda Alterwitz (Art + Science Editor of Lenscratch and Artist), Kellye Eisworth (Managing Editor of Lenscratch, Archivist, and Artist), Vicente Cayula Aliaga (Social Media Editor of Lenscratch and Artist), Alexa Dilworth (former Publishing Director, Senior Editor, and Awards Director at the Center for Documentary Studies (CDS) at Duke University), Kris Graves (Director of Kris Graves Projects, Photographer, and Publisher), Elizabeth Cheng Krist (former Senior Photo Editor with National Geographic and Founding Member of the Visual Thinking Collective), Yorgos Efthymiadis (Founder of the Curated Fridge and Photographer), Hamidah Glasgow (Curator and former Director of the Center for Fine Art Photography), Samantha Johnston (Executive Director of the Colorado Photographic Arts Center), Alayna Pernell (Lenscratch Editor, Educator, and Artist), Epiphany Knedler (Lenscratch Editor, Educator, Artist, and Curator of MidWest Nice), Jeanine Michna Bales (Beyond the Photograph Editor of Lenscratch and Artist), Drew Leventhal

(Artist, Publisher, and 2022 Student Prize Winner), Allie Tsubota (Artist and 2021 Student Prize Winner), Raymond Thompson, Jr. (Artist, Educator, and 2020 Student Prize Winner), Guanyu Xu (Artist, Educator, and 2019 Student Prize Winner), and Shawn Bush (Artist, Educator, Founder of Dais Books, and 2017 Student Prize Winner).

© Zahra Babaei, Outopia, 2025

Rochester Institute of Technology

MFA, Photography and Related Media

My Two Bodies

Rooted in the veiled experience of growing up in Iran, my practice investigates the thresholds between the seen and the felt. Fabric, both literal and symbolic, became the first interface: a medium of concealment, a second skin, a screen. It filtered my experience of the world and structured a sensual, often involuntary, awareness of being watched, touched, and obscured. These were early encounters with what I now understand as a form of embodied techgnosis, spiritual and haptic dimension of reality.

These photo-objects become part of an installation with projection, glass, as my tactile media ritual. The evanescence images in this project are not a representation, but residues that signal what is left behind after spiritual contact. Rather than producing legible narratives, I’m interested in generating zones of interference, where signal collapses into noise, and where the ghost in the image resists translation.

The covered female body, often othered and mythologized in Western media, becomes a site of spectral projection. She is both hyper-visible and absent, rendered in pixelated ideologies, coded, yet never fully a subject. My work channels this hauntology, not to resolve it, but to make its circuitry material. I tell her story in the third person: a woman who left the frame, but left fabric behind, an index of her refusal to participate in the ghost-making machine of representation. Into this absence, others arrive: Victorian mothers, colonial shadows, archival doubles.

Follow Zahra on Instagram: @zeebabaei

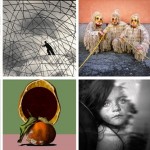

© Jaylen Brannon, The Hold, 2025

Pratt Institute

MFA, Photography

“What’s not to love bout it?”

In undergrad, at an HBCU, I learned some things about our history that I just can’t seem to shake outta my memory, and I kinda don’t want to. That knowledge changed what I choose to frame till this day. I photograph scenes that reflect America’s complicated story, especially the parts that don’t usually make the highlight reel. I know I won’t be able to frame the full picture in my lifetime, but I enjoy showing America for what it is.

As a kid, the term that I bubbled in on my scantrons “African American” always stumped me. I still don’t know if I fully understand it. My last name is Brannon, and that’s Irish. But that doesn’t make me Irish. Probably was from someone who claimed us, not someone we came from. At 22, I’m trying not to say “I hate America.” I’m looking at whats overlooked. Photography gives me time to sit with people, and in moments, and as time passes, I’m understanding that tenacity is the real American story. In a way photography is something that helps me finally start to answer the questions I couldn’t wrap my head around growing up.

I make the photos I needed to see as a child. Images framed by joy, freedom, peace, and a kind of silence from the outside world. For a while now, I’ve been drawn to graffiti; not the finished piece, but the process. Nobody shows the part where you’re walking 15 miles down train tracks at 3am, hopping barbed fences, just to paint something that might be gone by sunrise. It’s in that act I see “Black boy joy”; not staged, just lived. It’s one of the few spaces where Black men get to be boys again, free to explore, to wander, to create without rules. Even in the eyes of the police, you’re suddenly seen as a kid again. Spending all night painting something that might disappear by morning; it’s a feeling we know well, watching the things we care about disappear before we realize what they meant to us. So I photograph what I want to last.

Follow Jaylen on Instagram: @werunaways

© Ian Byers-Gamber, Archaeology, Holly Grove (Hands), 2024

Rutgers University

MFA, Visual Art

I Come Creeping

My research interests arise from long-standing bonds with friends, colleagues, and oft-visited institutions. As the camera helps me gain access to non-public spaces, my photographs record my subject and my own involvement. Invested in the slow processes of large-format and darkroom production, the act of photography becomes a research method. While archives and institutions necessarily arise from and reproduce imperial power, I investigate these forms, searching for the cracks in their foundations: spaces of radical potential, opening to possible futures. I aim to turn the camera against its imperialist past. Grounding my research in an artistic subjectivity—a subjectivity inseparable from my community—enables the liberatory political imagination that motivates me.

I examine and experiment with exhibition conventions to draw suspicion on the exhibition form itself. To disturb the conventional museum experience I ask the audience to question its expectations of institutional looking. In a recent show on the West Virginia mine wars, I evoked the modern art museum by installing a restrained, documentary-style photograph of a West Virginia landscape, generously matted in a thin black frame; across the room, I installed staged and lit tableau photographs of contemporary leftists in custom artist frames, made of red oak and embellished with bullet casings. These framing strategies challenge the immanent authority of the museum. This is why I appropriate institutional forms: to turn them against themselves.

In seeking out and producing liberatory moments, my work suggests new ways of engaging with our cultural institutions and archives, marking new paths on their imperial blueprints.

Follow Ian on Instagram: @bamblerdander

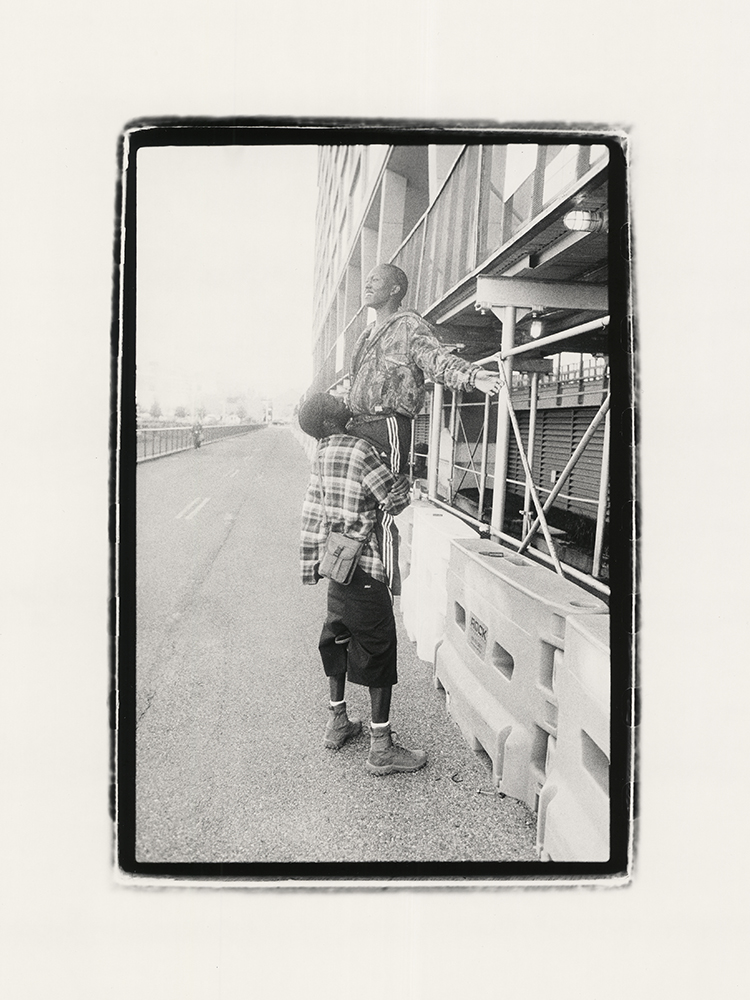

© Beihua Guo, 3641-11655: Jinan Zhangzhuang Air Base, 1956; Zhangzhuang Airport Culture Park, Jinan, 2024 (printed 2025)

University of Arizona

MFA, Photography, Video and Imaging

Designated Ground Zeros

The Atomic Weapons Requirements Study for 1959, produced by the United States Strategic Air Command (SAC) in 1956 and published by the National Security Archive at George Washington University in 2015, is the most comprehensive record of Cold War nuclear targets ever declassified. Spanning over 800 pages, this document lists the coordinates of more than 4,500 nuclear targets across the Soviet Union, China, and Eastern Europe.

I travel to the nuclear targets in China identified by the SAC in 1956, documenting these sites through photography and creating radioactive uranotypes using the uranium printing process. Many of these sites have undergone dramatic transformation: the once-abandoned Shougang Steel Mill in Beijing became the Big Air venue for the 2022 Winter Olympics; warehouses, airport hangars, and fuel tanks along Shanghai’s Huangpu River now house contemporary art galleries and museums; coal mines in Fushun and Dayu have been repurposed into educational and recreational zones. These seemingly mundane landscapes are, in fact, sites marked by deep historical trauma—legacies of imperialism, Cold War tension, and China’s evolving identity.

Number of nuclear targets photographed: 48 of 368 (as of May 21, 2025).

Follow Beihua on Instagram: @beihua_guo

© Alexis Joy Hagestad, this forest remembers fire installation view, 2025

University of Arizona

MFA, Photography, Video, and Imaging

this forest remembers fire

this forest remembers fire is an installation that explores the consequences of fire suppression in the United States, particularly in the context of climate change. While containing individual wildfires may provide immediate safety, the aggressive suppression of all fires can lead to dangerous fuel buildup, resulting in more intense wildfires. This shift away from Indigenous land management practices—where cultural and controlled burns promoted ecosystem health—began after colonization and the catastrophic fires of 1910. These events framed fire as solely destructive, overlooking its regenerative potential.

Grief is like a forest after a wildfire. After my grandmother’s death in 2017, I spent the summer as a wildland firefighter, witnessing firsthand the transformation of forest ecosystems in the wake of fire. After a wildfire, the forest may appear desolate, with charred remnants indicating what once thrived. However, fire is crucial in healing certain ecosystems and integral to many landscapes.

This installation features a fictional forest after a wildfire. The burned and charred forms serve as reminders of past fires and their impacts. As climate change accelerates, society must reevaluate its relationship with fire, acknowledging its destructive potential and vital role in renewal. Rather than merely “fighting fire,” we should seek ways to coexist with it, embracing its place in our ecosystem. This forest embodies the dual nature of fire: a force of destruction and a catalyst for regeneration.

As I navigate my grief over losing my grandmother, I have learned about resilience through the natural healing processes of forests. Fire can promote growth, even when signs of renewal are not immediately evident. Some forests may take years or even decades to recover from a fire, but that doesn’t mean they aren’t recovering. Just as ecosystems rejuvenate themselves, grief also unfolds on a different timescale.

Follow Alexis on Instagram: @ajhagestad

© Misael Hernandez, Mamma (Tablet No.1), 2025

University at Buffalo

MFA, Studio Art

Frontera de cáracter

Frontera de carácter utilizes photographs, appropriated archives, and adobe building material to express my Mexican American experience. I handcraft adobe hybrid tablets embedded with prints to create a tangible archive consisting of familial photographs, many of which I recently acquired from various family members specifically for this series, and photographs from my personal image archive. I value the modularity they allow when considering how familial photographs from Mexico can interact with personal photographs from my experiences in Northwest America. The tablets become more than history in their activation of fossil and cultural material to lay a physical and metaphorical foundation for my work as a Mexican American. Each one becomes a partial pocket of memory never fully explained, resurfacing through the extraction of earthly materials.

In parallel, I also utilize archival-sourced images and hand-make adobe bricks to construct cultural, religious, and landscape-centered compositions related to my Mexican heritage. These compositions are carefully staged and photographed using a medium-format film camera. Including sourced historical photographs helps me establish a layer of internal processing in a way that traditional photographs cannot achieve. The compositions become self-portraits as reflections of myself begin to form out of the constructed monuments. The two bodies of work clash to provide an experience reflective of labor, photographic deep-time, and cross-cultural memory.

Follow Misael on Instagram: @misaelhdzstudio

© Isabella Kahn, Annie Morgan – Guangdong, Guangzhou, 2005, 2025

Drexel University

BS, Photography

32 Years Later: The Legacy of Chinese Intercountry Adoption

32 Years Later: The Legacy of Chinese Intercountry Adoption is an ongoing series of portraits that focuses on themes of self-definition, growth, and resilience among Chinese transnational adoptees. Following the Chinese Government’s recent and sudden decision to end their foreign adoption policy, over 160,000 of us worldwide are now left to reflect on its three decades of history and nonexistent future. This conversation is extremely complex and important within contemporary dialogue, intersecting with issues of immigration, citizenship, and cultural representation. 32 Years Later recognizes the individuals impacted by the personal and political legacy of this history, analyzes how we as adoptees collectively fit under this shared identity, and celebrates the ways we have grown beyond it. For me, this represents one of the community’s many efforts to connect and heal as a diaspora of displaced peoples.

Follow Isabella on Instagram: @isabellakahn

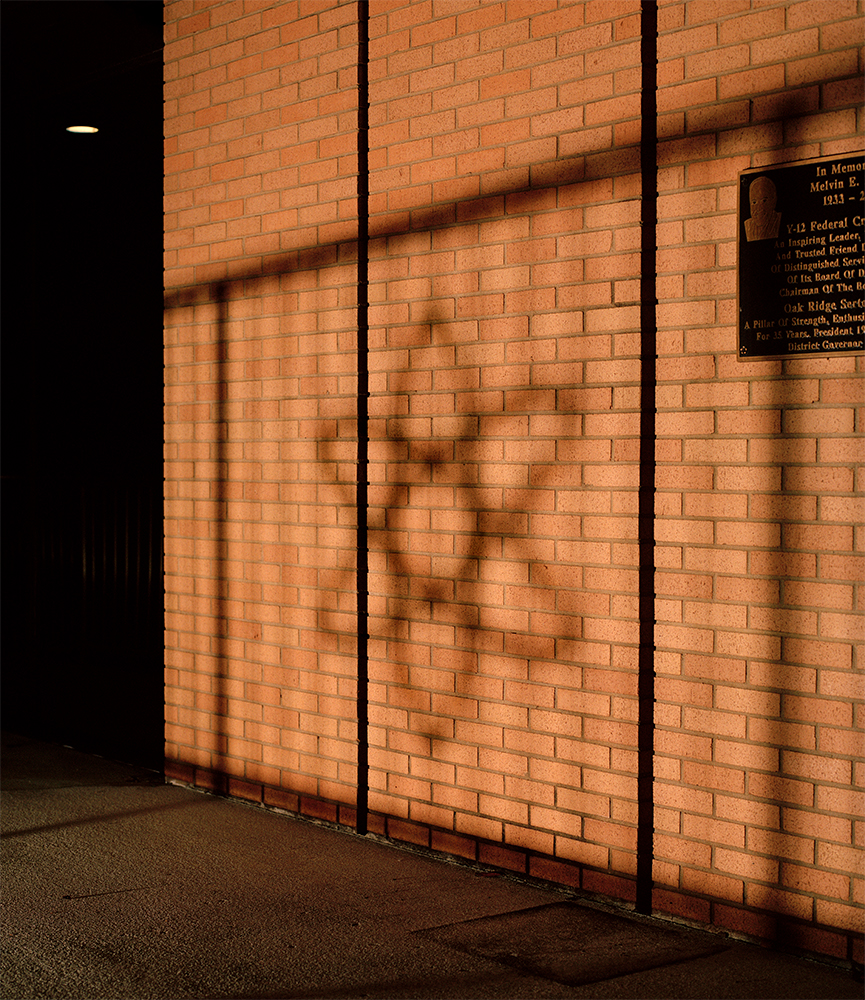

© Ross Landenberger, Y-12 Federal Credit Union entrance, 2023

Georgia State University

MFA

To Snare the Sun

I was raised in Oak Ridge, Tennessee, a town that was secretly formed and constructed in 1942 as part of the Manhattan Project. Growing up queer in East Tennessee, I became highly aware of an unchecked masculinity embodied through rugged individualism, Southern family values, and the legacy of the atomic bomb. These elements of my town’s culture were relentlessly focused on projecting strength, yet it was this very emphasis that made those who fell outside of that expectation feel weak. To Snare the Sun explores the creation of the atomic bomb as a stand-in for American masculinity and hubris in my hometown. Oak Ridge was built to achieve a militaristic goal. I want to know what it means to live in the shadow of that creation and navigate the legacy it left behind.

Follow Ross on Instagram: @rosslandenberger

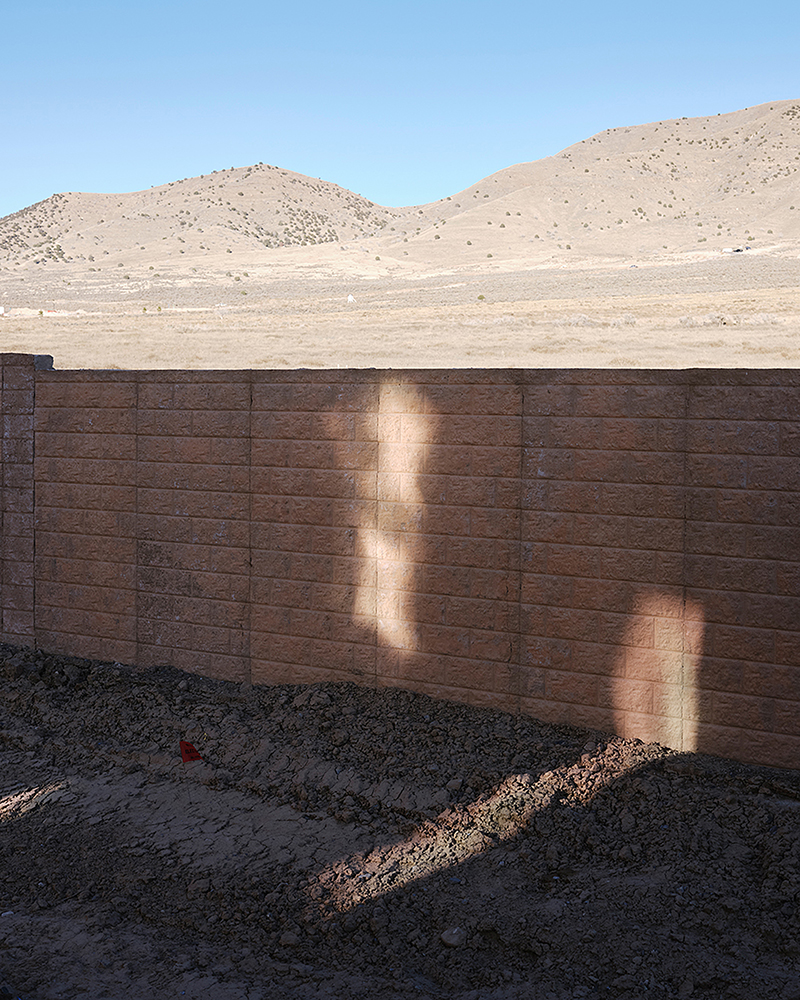

© Jordan Layton, flux 3, 2024

University of Utah

MFA, Art

anew eden

I’m drawn to the spread of suburban sprawl into Utah’s West Desert. Here, the meticulous, uniform rows of new development are starkly contrasted with the rugged, natural beauty of the desert landscape. The white vinyl fences prominently featured in these landscapes reflect growing divides, manifesting the barriers that have emerged not only in our neighborhoods but within our social fabric. More than simply documenting the physical growth of suburban sprawl, I emphasize the growing tension between the individual and the collective. anew eden is an examination of the deeper issues of alienation and disconnection fostered by a society controlled by capitalist values. It challenges viewers to reconsider the concepts of belonging and community in an era where economic concerns often overshadow the intrinsic human need for connection.

Working across video, photography, installation, and performance, I utilize both natural and manufactured readymades as a visual vocabulary. By repositioning these objects within contradictory or sometimes absurd scenarios, I reconsider their roles as symbols of modern power dynamics and their impact on our collective psyche. These items, familiar yet displaced, become conduits for reflection on the systems that govern our lives and the alienation they foster.

Follow Jordan on Instagram: @jordanlayton

© Christian Lee, The Princess, Crenshaw, 2025

University of California, Los Angeles

BA, Art

The Warmth of Other Suns

My family settled in South Los Angeles upon emigrating to the U.S. I remember late afternoon drives down Western Avenue and spontaneous visits to Crenshaw, where we stood before the tiny apartment my father and his siblings grew up in. The relationship my relatives shared with the city unfolded as a complex interplay between sorrow and joy, struggle and success—the frequently synthesized immigrant narrative began taking dynamic shape as we attended the Annual Kingdom Day Parade. Honoring Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.’s legacy was instrumental to the progress of our respective communities and the deep impact that Dr. King’s heroism had.

It allows us to confront a complex history layered with tension, injustice, and violence. This region of the city has not always been unified, however, as my loved ones remind me, we never cease to rebuild. The wildfires and widespread hatred threatened to prevent us from uniting. The Kingdom Day Parade was cancelled, and many Los Angelinos were mourning.

Still, we found a way to heal.

Attending the rescheduled Dr. King parade was a beautiful demonstration of solidarity in a time where apathy seems prevalent. When I interacted with those children spectating curiously from their porches or the families cheering under our city’s palm trees, I saw a future. I saw hope.

Photographing reminded me that the camera could be used to restore dignity and agency to communities often erased from the larger story of American life.

Follow Christian on Instagram: @christianmakesfilms

© Sungchul Lee, The Stranger, 2024

Rhode Island School of Design

BFA

I explore the unconscious dimensions of space through photography, video, installation, and performance.

Follow Sungchul on Instagram: @leeleedug

© Montenez Lowery, Aziza Hunt and her daughter Emoni, Locs Pinhole, hair from subject laid on film, 2024

Georgia State University

Photography

A Darktown Cakewalk

A Darktown Cakewalk is a pinhole camera project that takes its name from a minstrel show. The history and performance of the show is rooted in both mockery and resistance, a cycle of appropriation that is central to my project. A Darktown Cakewalk critiques the medium’s history as a tool used to reshape, erase, and exclude, and asks what it means to hold space for Black identity on our own terms.

The work begins with a question I ask each of my collaborators: What object represents your Blackness, but has either been appropriated or lost to the mainstream? Each object offered is then transformed into a functioning pinhole camera. Through this process, photography becomes more than a tool of representation, it becomes a site of ritual and reconnection. I put the product from the item on the film or use the photogram method to infuse the person’s image with the object, making it so that one cannot exist without the other. A representation of how the identities are tied to these cultural objects.

I love my culture, and through this work, I aim to make visible not only the deep connections we have to these cultural symbols but also the ways so-called “ordinary” objects hold memory, meaning, and history. A Darktown Cakewalk is both a response to the present moment and an invitation: for Black viewers to rediscover and reflect on their culture in new ways, and for others to feel, even for a moment, what it means to be connected to it.

Follow Montenez on Instagram: @Montenez.l

© Nika McKagen, Cave Tainaron Where Black Smoke Billowed, 2025

University of Wisconsin-Madison

MFA

Karst

My project Karst considers the idea of a katabasis, a mythic descent into the subterranean underworld, as an allegory for exploration into memory and the subconscious. Through this journey, boundaries thin, allowing the body to transgress into another realm. This project documents cave systems in the Appalachian Mountains in Southwestern Virginia that my late father and I explored as a child. In 2024, twenty years after his death, I descended back into these caves. Karst follows a loose narrative of this katabasis into the subterranean world, and consequently into memory. The resulting photographs act as evidence of mythic, poetic, and subconscious spaces that explore the visual reconstructions we create while trying to understand time and loss.

The images in Karst are printed on expired silver gelatin paper. This paper has been scarred by light over the course of its lifetime, allowing the imagery that etches into it to reflect the dim conditions of the underworld. The formal photographs in this project also contains works utilizing handmade abaca paper, silver nitrate emulsion, and reprinted archival ephemera of my father caving from 30 years ago. All of these documentations are then transformed into photographic collages of visceral textures, obscured ghosts, and portals into other realms. The work is installed in handmade wooden frames, slabs, and signposts.

Follow Nika on Instagram: @1889__lover

© Meeker, Fading Roots: A Living Ghost, 2025

Baylor University

BFA, Photography

Fading Roots

I am a visual artist, environmentalist, and wildlife photographer from Louisiana, where the wetlands shaped my earliest understanding of beauty, resilience, and impermanence. As a BFA student concentrating in Photography at Baylor University, my practice blends fine art and environmental advocacy. I use digital and alternative photographic processes to explore the fragile connections between humanity and the natural world, striving to create work that sparks both reflection and action.

My current series, Fading Roots, examines the rapid disappearance of southern wetlands—landscapes that have sustained life for millennia and now face devastation from climate change, industry, and neglect. Cypress trees, once standing as guardians of these ecosystems, are falling. Every 2.7 miles of lost wetlands increases storm surge by a foot, and Louisiana loses a football field’s worth every 100 minutes. These aren’t just facts—they’re warnings. My images layer quiet, ethereal landscapes with historic and projected maps of wetland loss and texts from Darwin and Odum, illustrating what’s vanishing and what’s at stake.

Growing up near these wetlands, I’ve witnessed their erosion not just in the land but in public memory. My work seeks to reclaim that memory, to remind viewers of our intrinsic link to these spaces. By merging scientific research with poetic visual language, I hope to challenge viewers to see differently—to care, to grieve, and ultimately, to act. The land is speaking. I am trying to listen—and to help others hear it too.

Follow Madalynne on Instagram: @madalynnemeeker.imgs

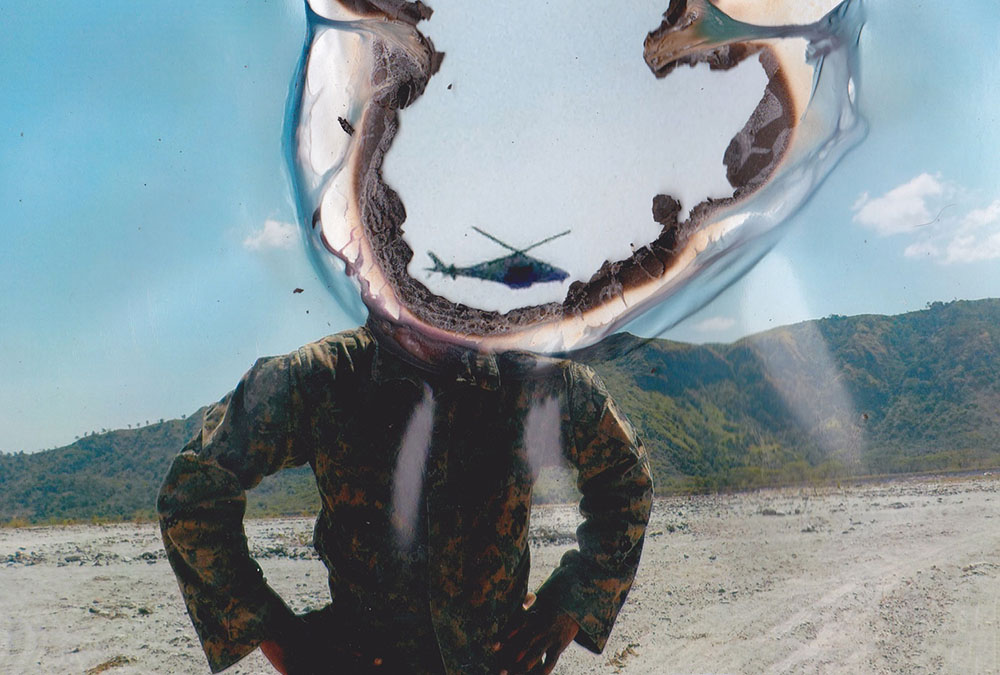

© Ryan Mitchell, First Time Outside, 2023

Syracuse University

MFA, Photography

Thank You, For Your Service?

Thank You, For Your Service? explores memory culminating in frustration, anger, and violence, which led to emotional withdrawal and physical stress from my military service experiences. I work with the 4×6 photographs taken on deployments during my four years in the Marines, utilizing collage techniques to express the fragmentation resulting from these memories. These recollections are a view into goals never achieved, training for a war I never saw, the transitional phase of being thrown back into civilian life, and the haunting regret and self-doubt while seeking new potential and purpose.

The collages are constructed with fragments from the textures and scenes soldiers are surrounded by — weapons, fatigues, helmets, and the desert. I create small and sometimes miniature-scale works. It is an emphasis of not only a contrast in the lack of control I felt while serving but also the shame I feel in not being able to see what is considered the pinnacle of a soldier’s duty: experiencing combat. This creates a sense of preciousness and materiality that reminds me that I served honorably. Second, the labor used in making these works serves, as a therapeutic way, to address and critique the hidden desires I wanted to experience, such as protecting my country through combat. I use these objects or photographs to create a sense of acceptance of those themes. The glorification of killing another human being and acting as a destructive force of nature is falsely praised.

Follow Ryan on Instagram: @tiermir

© Joshua Mokry, Repair, 2025

Texas Tech University

MFA

Underearth

This body of work spans twelve different cave systems in the regions of New Mexico and Texas where I have been working as a cave restorationist. The objectives of these trips are to restore parts of a cave that have been polluted and trashed, repair formations that have been broken, and catalog cave life. Serving as both photographer and restorationist, I am constantly thinking about how far human interference can extend itself. I further question the importance of this restoration, and how both destruction and restoration privileges human vision over nonhuman habitation.

Human influence on our environment has seeped below our awareness. Placing my body below the Earth, I bring myself below to raise up things not heard, felt, or thought about. I reckon with forces that move on a different time scale from our own but are nevertheless moving whether we perceive it or not. Caves are measured, inspected, and treated as evidence for us to exploit. It is in these places where human involvement extends itself. I am at the mercy of the rocks, the objects, and the shadows. I focus on these nonhuman spaces to challenge our hierarchy and put us below the horizon line.

Follow Joshua on Instagram: @jamokry

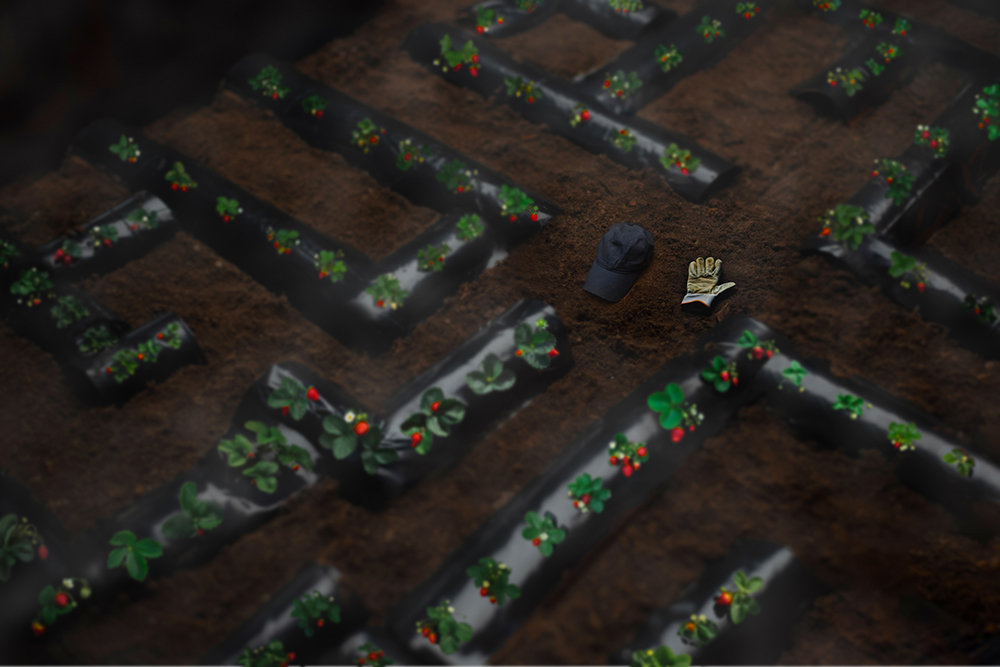

© Emilene Orozco, The Labyrinth of Labor, 2025

California State University, Long Beach

BFA, Photography

Invisible Labor

As a first-generation Mexican American artist, I create work that honors the unseen labor and generational resilience that shaped my upbringing. My project Invisible Labor is a visual reflection of the immigrant workforce, particularly those whose hands build, clean, and feed this country, yet are rarely acknowledged. Through staged photographs, textile references, and poetic symbolism, I aim to humanize those rendered invisible by systems of exploitation.

This work is deeply personal. My father worked in the fields of California, and my mother has held various domestic jobs. Their stories, sacrifices, and silences are embedded in each image. I approach photography not just as a tool for documentation, but as a space for resistance and reclamation, where I can stage scenes that reframe power, dignity, and cultural memory.

I hope this series encourages viewers to pause and consider the labor behind everyday conveniences. My goal is to continue creating work that speaks to community, challenges harmful narratives, and offers space for healing. Receiving this opportunity would further affirm the importance of centering stories often left out of mainstream visual culture.

Follow Emilene on Instagram: @emilenephoto

© Gabriela Passos, Building in America, October 18th, 2024

George Washington University

MA, New Media Photojournalism

Building in America

Building in America is a personal reckoning with a story I’ve lived but never seen told. As a first-generation Brazilian-American whose family has worked in Florida’s construction industry for decades, I grew up surrounded by drywall dust, job site stories, and the quiet endurance of undocumented laborers. This multimedia project is my attempt to honor those workers—people like my parents, siblings, and neighbors—who have built the homes of others while being denied stability themselves.

Through photography, video, sculptural installation, and long-form reporting, Building in America investigates the intersection of immigration policy, labor, and housing in the United States. It asks: Who builds our homes, and who gets to live in them?

This work aims to raise awareness of the immigrant communities who physically build the environments we inhabit and to spark critical conversations about how we perceive and value labor. It challenges audiences to confront the contradiction at the heart of American prosperity: that the growth we celebrate is often built on the backs of those we render invisible. Ultimately, it invites us to acknowledge our collective complicity and imagine a more inclusive, equitable future—one in which those who build our homes are no longer excluded from the stability they help create.

What began as documentation has evolved into a collaborative practice rooted in community. At its core, Building in America is about visibility, dignity, and the right to lay down roots—and to be seen as essential, not expendable.

Follow Gabriela on Instagram: @gabrielapassos_photography

© Hannah Samoy, Balikbayan, 2024

Milwaukee Institute of Art & Design

Fine Art New Studio Practice, Arts Management

Balikbayan

What has been forgotten? The negative space is where this seemingly unanswerable question exists. It is where I contemplate my access to memories or what I allow myself to have access to. I attempt to bridge inherited and personal gaps by working with the people and places that remain. The distance between is my craving to know more and my capacity to have more.

An archive of stories from my parents and grandparents holds a lot of space in my memory. Their words form images in my mind, ones built from recollections, longing, and the quiet spaces left by what was forgotten. In December 2024, I traveled to the Philippines, documenting my own experiences as I met the people and places I had only previously heard about; a second-hand familiarity. My photographs reach into those spaces, connecting my personal stories to the ones passed down to me. It is a practice of preservation, but also of acceptance—of what remains, of what fades, and of what is inevitably transformed in the act of remembering.

Balikbayan is a visual meditation on return, longing, and partial belonging. The term itself refers to a Filipino returning to the homeland after living abroad, and it encapsulates the tension I explore in my photographs: of being both from and apart as a second generation Filipino American.

Follow Hannah on Instagram: @biyayaart

© Hannah Schneider, from the series When will I go blind?, 2025

Duke University

MFA, Experimental and Documentary Arts

When will I go blind?

If a camera can be compared to an eye, a disintegrating negative can be compared to a diseased retina. In this work, When will I go blind?, I use antiseptics, dry eye ointment, and boiling water to disintegrate images that feature the people, places, and things that bring me joy. As a photographer with Bardet-Biedl Syndrome, I am terrified and anxious about losing my vision. Without being able to see, I will be limited to my visual memories and not be able to engage with the world the way I used to. What will happen if these memories fade? Will I lose part of myself by having to engage in the world differently? I made this work while I am still sighted as a coping mechanism to process the initial stages of the disease. I hope this work connects with others who have gone through something similar.. For people who have never experienced anything like this, I invite them to visualize and feel my fear of loss through this work.

© Anastasia Sierra, Escape, 2025

Massachusetts College of Art and Design

MFA, Photography

The Witching Hour

I become a mother and stop sleeping through the night. Years go by, the child sleeps soundly in his bed but I still wake at every noise. My father comes to live with us and all of a sudden I am a mother to everyone. As I drift off to sleep I can no longer tell my dreams from reality. In one nightmare my father tells me he’s only got two weeks left to live, in another I am late to pick up my son from school and never see him again. I am afraid of monsters, but instead of running, I move towards them: we circle each other until I realize that they are just as afraid of me as I am of them.

My images follow the logic of my dreams, where we are trapped in a strange colorful world, playing a never ending game of hide and seek in a labyrinth of love, care and fears, pushing against its walls, with no way to escape but wake up.

This work explores the emotional landscape of caregiving: tenderness, beauty guilt, and a constant sense of what could be lost.

Follow Anastasia on Instagram: @anastasiasierra

© Erika Nina Suárez, Outhouse, 2025

Moholy-Nagy University of Art and Design

MA, Photography

Seasons In The Sun

My community has dreams that exist outside of your world. A world built on promises never meant to be kept, especially not by those of us left to deal with the destruction of generations who reaped the earth’s rewards first. We are young, and we just want to escape all of this. To

farm. To grow things. To show up to parties with dirt under our fingernails. We’re assembling a life from scraps left behind, an existence that was never designed to be built by us in the first

place. So, we’re rigging it.

At the center of this ongoing project is Lujza, a 25-year-old chef in Budapest with dreams of becoming a doula, transforming her garden into a birthing center, and growing more things as she ages. She dreams of this and of building a lifelong community. It’s the kind of vision that feels like it belongs to someone much older, but she carries it with a youthful sort of conviction. A conviction that is as deep as the plants she grows and carries to the restaurant she cooks in.

This series documents a growing movement among young people in Hungary who are roughly between 18 and 30 and have come to realize that a traditional life in the city is no longer accessible. Many young people were told that if they worked hard and got degrees, they could have what their parents did. But now, as adults, we see that world slipping further away. Some of us are choosing to step away and build a simpler life, acquired by any and all unconventional means, in order not to be crushed by rent increases, low-paying jobs, and the chokeholds of capitalism and bad government. Sometimes that means leaving the city. Sometimes it means seven roommates.

Lujza and I both exist outside of this trick mirror now. We plant, we grow, and we lie under the sun. I no longer want to climb a corporate ladder or work a 9-5 job when I have more time to tend to myself and have just enough to get by. Aren’t you wondering what we’re doing out here, when we could be with the rest of the world?

This is about Lujza, but also about all of us. It’s about imagining new futures from what we were never supposed to inherit. I’ve shared meals, beds, and sweat with thirty people under one roof. At nineteen, that was what community looked like. It also looked like bathing outside and building a greenhouse. It felt like fire, and pain, and absurdity. It’s a quiet act of rebuilding while the world around us cracks open.

Follow Erika on Instagram: @erikaninasuarez

© Brianna Tadeo, Breathing Rocks of my Past, 2025

The University of New Mexico

MFA, Studio Arts

These fleeting shadows dissolve by day’s light

I often think about the Giant Camera at Ocean Beach in San Francisco, a unique pale-yellow building built in 1946. Inside the almost pitch-black room sits a massive bowl, where one sees a moving 360-degree projection of the ocean and cliffs beaming down from a hole in the ceiling. While I have seen other camera obscuras, this one captivates me with its mesmerizing display of light and the image of crashing waves reflected in the bowl below—Like a breathing image. What magic does a photograph hold? What does it mean to embrace decay in an analog process meant to last? What do these light-sensitive materials reveal through disintegration? While photography aims to capture moments, what if we became the camera ourselves? Our eyes as lenses and bodies as sensors allow us to appreciate the beauty of transience. There’s beauty in the fleeting nature of experiences, reminding us that both images and moments evolve. My exhibit captures shadows of significant places, now either vanished or accessible through images and sound. These fleeting moments highlight the essential role of light in photography, which feels magical to me. At its essence, creating an image requires just light and a pinhole—how can that not be magical?

Follow Brianna on Instagram: @brianna_tadeo

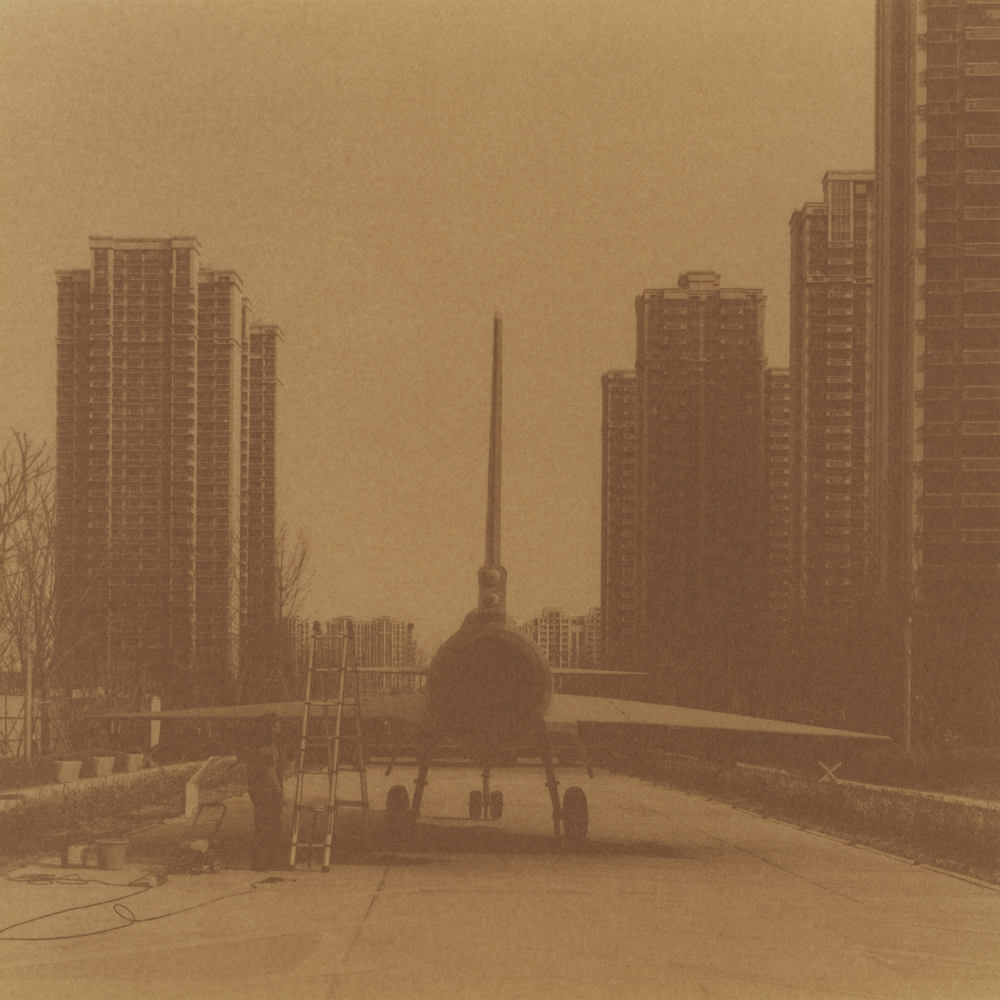

© Jordan Tovin, from the series Shaw Diary, 2023

Corcoran School of Art and Design

BFA, Photojournalism

Shaw Diary

As a documentary photojournalist, I’m driven by a deep curiosity about the everyday moments that define our lives. I believe the most powerful stories are often found in the seemingly mundane, in the small details of daily life that reveal the intersections of history, community, and culture. Through my photography, I seek to highlight these moments and explore how personal narratives are shaped by the broader societal forces around us.

Currently pursuing a BFA in photojournalism at the Corcoran School of Art and Design in Washington, D.C., I’m focused on long-term visual projects that dive deep into the lived experiences of communities. My work is centered on capturing authenticity—documenting people’s stories in a way that respects their realities and amplifies their voices. I aim to tell stories that reveal the complexity of human experiences, whether they involve moments of struggle, joy, or quiet resilience.

For me, photography is a tool for connection. It’s about finding common ground and shedding light on stories that might otherwise go unnoticed. My goal is to create work that encourages empathy and understanding, giving viewers a chance to see the world through the eyes of others. I believe that the best documentary work has the power to change perceptions and spark conversations, and that’s what drives my passion for this medium.

Follow Jordan on Instagram: @jordan.tovin

© Judson Womack, Candelabra, 2024

Columbia College Chicago

MFA, Photography

Lay Us Down

Out in the Deep South, there’s a cemetery where my entire family is buried. My living grandmother has her headstone. My parents and I have plots. I’ve shivered atop my grave, not only at inevitable death but at this other event. My existence and eventual nonexistence inhabit this form simultaneously. The catastrophe has, in a way, already happened.

I believe I’ve absorbed, embodied, something of this place. Narratives inhabiting any landscape will seep into the young mind. And so this work—chasing this internal dialogue manifesting in the chaos of the tangible world, has been for that transferred essence I believe can be simplified to “death,” or an awareness of death; a creeping, childhood knowledge coloring every moment of joy and despair. Death lies at the heart of this place—my place, both literally in my grave and conceptually in my understanding of this place’s society and culture; the Gothic, maybe, at the heart of my Southernness.

So what does it mean to photograph here? The camera also binds existence and nonexistence to a singular form simultaneously. This apparatus imposes an essence of death, so might I give these subjects rest by making their photograph—lay them down? Or might I revive them for all time, as evidence I saw them in this way?

Lay Us Down is this meditation; a fragile collection of images depicting home, family, belonging, whose subjects inhabit fleeting moments, like me, between our own catastrophes. Maybe each photograph, like my plot, is that catastrophe already.

Follow Judson on Instagram: @judwomack

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

Carolina Baldomá: An Elemental PracticeJanuary 5th, 2026

-

Time Travelers: Photographs from the Gayle Greenhill Collection at MOMADecember 28th, 2025

-

Suzette Dushi: Presences UnseenDecember 27th, 2025

-

Ragne Kristine Sigmond: Portraits of Painterly LightDecember 2nd, 2025