Celebrating 20 Years of Critical Mass: Jennifer McClure (2017) and JP Terlizzi (2018)

Photolucida is a Portland-based nonprofit dedicated to providing platforms that expand, inspire, educate, and connect the national and international photography community. Critical Mass, Photolucida’s annual online program, is designed to foster meaningful connections in the photography world. Open to photographers at all levels, anywhere in the world, participants submit a portfolio of 10 images. Following an initial pre-screening, 200 finalists are selected to have their work reviewed and voted on by up to 200 distinguished international photography professionals. From this process, the Top 50 are chosen, and a range of awards is presented. Submissions open each June.

In 2025, we celebrate the twentieth year of announcing the Critical Mass Top 50 finalists! We are honored to partner with Lenscratch to reflect on this history through a special series highlighting two artists from two different years in each post. Each featured artist offers a window into the diversity of projects and voices that make up Critical Mass—from documentary and narrative photography to conceptual, photo-based practices. These Q&As share the history, intention, and trajectory of the artists, pairing their Critical Mass portfolios with newer work.

For Critical Mass 2025, we received submissions from artists across 26 countries, tackling subjects in countless styles—from black-and-white and digital photography to chemigrams, cyanotypes, photographic sculpture, and textiles. Our esteemed jurors, representing a wide range of global perspectives, dedicate their expertise and thoughtful consideration to this process, often leaving feedback and encouragement for the artists.

Critical Mass continues to elevate emerging photographers, providing a platform that amplifies their voices to broader audiences and to the industry professionals who help shape careers. We are deeply grateful to everyone who makes this possible.

Jennifer McClure 2017

In her photography, Jennifer McClure turns inward, using the camera as both mirror and microscope. Her Photolucida Critical Mass 2017 Top 50 series Laws of Silence traces the ways memory, fear, and expectation shape a life, rendering emotions almost like specimens pinned to a wall. In her more recent project How Easily We Are Undone, she shifts into the intimate terrain of early motherhood, documenting the joy and terror of raising a child through a global pandemic. Across these bodies of work, McClure grapples with identity, the weight of cultural narratives, and the lifelong process of learning how to hold—and release—our most vulnerable truths.

Jennifer McClure is a fine art photographer based in New York City. She uses the camera to ask and answer questions. Her work is about longing, solitude, and an ambivalent yearning for connection. She often uses herself and her experiences as subject matter to explore the creation of personal mythology and the agency of identity.

After an early start, Jennifer returned to photography in 2001, taking classes at the School of Visual Arts and the International Center of Photography. In between, she acquired a B.A. in English Theory and Literature and began a long career in restaurants. Most of her projects today incorporate her love of literature; one series was inspired by a short story, another includes photos of transformative texts, still another draws titles from a long-form poem.

Jennifer was a 2019 and 2017 Critical Mass Top 50 finalist and twice received the Arthur Griffin Legacy Award from the Griffin Museum of Photography’s Juried Exhibitions. Her first book, You Who Never Arrived, was published as one of nine Peanut Press Portfolios in 2020. She was awarded CENTER’s Editor’s Choice by Susan White of Vanity Fair in 2013 and has been exhibited in numerous shows across the country. Her work has been featured in publications such as National Geographic, Vogue, GUP, The New Republic, Lenscratch, Feature Shoot, L’Oeil de la Photographie, The Photo Review, Dwell, Adbusters, and PDN. Lectures include the School of Visual Arts i3: Images, Ideas, Inspiration series, Fotofusion, FIT, NY Photo Salon and Columbia Teachers College. She has taught workshops for Leica Akademie, International Center of Photography, Los Angeles Center of Photography, PDN’s PhotoPlus Expo, the Maine Media Workshops, the Griffin Museum, and Fotofusion. She was a thesis reviewer and advisor for the Masters Programs at both the School of Visual Arts and New Hampshire Institute of Art. She founded the Women’s Photo Alliance in 2015.

Instagram: @jmcclurephoto

Q: Can you tell us how you first learned about Photolucida’s Critical Mass, and what motivated you to enter?

JM: I attended the Photolucida portfolio reviews in 2013, and several reviewers encouraged me to submit. The project was still in its early stages, but I made it into the Top 200. I kept photographing, refining the work, and developing the writing. In 2015, I applied again and was rejected. By 2017, I had finally completed the project and entered because I wanted to give it my best with finished work. I knew Critical Mass would allow the series to be seen in its final form by more people than I could ever reach on my own.

Q: You describe the work from your Critical Mass 2017 Top 50 portfolio, Laws of Silence, as a way to “pin” feelings to the wall in order to examine them—almost like specimens. How does photography function for you as both containment and release of memory and emotion?

JM: I grew up in a family that didn’t know how to handle big emotions, so I learned early to hide mine. But they never really went away, and I developed a lot of faulty coping mechanisms. Eventually, I discovered that when I was confused or overwhelmed, I could make pictures—and they would give me clues about what I was actually feeling. When memories and emotions spin around in my head, they build power. But once I can visualize and name them, they lose their hold. The act of making photographs and listening to what they reveal helps me put them in perspective.

Q: In your artist statement, you’ve expressed skepticism about the American Dream and its prescribed markers of success. How did that perspective shape the way you composed or selected images for Laws of Silence?

JM: The project I made just before this one examined why all my relationships had failed. At the end, I realized I was questioning why I felt I needed to be in one at all. That led me to interrogate where my notions of success came from. My parents believed that checking off the boxes—house, job, marriage, kids—meant you were successful. I realized I’d been photographing those boxes all along, often unintentionally. For Laws of Silence, I selected images that either exaggerated those markers or pushed them into the distance, reflecting both my past and where I was at that time.

Q: Water recurs in your imagery as both destructive and sustaining. How did you decide to weave that duality into the series, and what did you hope it would communicate?

JM: I didn’t set out to use water metaphorically, but I kept being drawn to it as I made new photographs. Everything clicked with the image of the swimmer underwater, surrounded by bubbles. It brought me back to a complicated childhood memory of a terrifying swimming experience. Rebecca Norris Webb describes editing as a “re-vision process,” trusting that images are wiser than we are. For me, water became a metaphor for my relationships—filled with fear rooted in memory rather than calmness and support. That realization helped me choose which early images to include and guided the final selections. I ended the series with a floating image, to suggest that letting go of all that tension was ultimately healing.

Q: You’ve said you learned “how to be alone without being lonely.” Does the series document a resolution in that journey, or is it more about living with the tension of longing and absence?

JM: At the time, it felt like a resolution. I had let go of other people’s expectations for my life. My next series focused on single people, since I assumed I’d be single forever. Many of those I photographed had been married or partnered and now chose solitude, but a large number—myself included—had never been in a relationship at all, often because of fear. I wasn’t lonely, but I realized I wanted to overcome that fear and truly love someone. What felt like resolution actually opened the door to an entirely new longing I didn’t anticipate.

Q: In your more recent work How Easily We Are Undone, you describe photography as salvation, a way to surface buried memories. How did photographing in those early years of motherhood help you process both joy and powerlessness?

JM: At first, I was too exhausted to photograph anything. Creativity felt impossible. I only started again when my daughter stopped breastfeeding. I had been clinging to my plan and placing too much importance on it. Photographing my struggle showed me how much I was trying to force the situation, and it became clear that so much was going to be out of my control. That realization freed me to photograph everything, including the joy. Becoming a parent means confronting your own childhood—you’re reliving those years through a new lens. It’s a kind of re-mothering. I consciously made space for the full range of emotions.

Q: The pandemic intensified both closeness and fear. How did that heightened time shape the emotional tone of the photographs?

JM: Every day in the early pandemic felt terrifying. I had this family I never expected, and suddenly I feared losing them. Emmet Gowin says you can’t set out to photograph love—but if you are in love, it comes through. I was filled with love and fear, and that duality shaped the images. There are deep shadows punctuated by bursts of light, and very little physical distance between us as subjects.

Q: As your daughter grows, you’ve reflected on what she may carry from these early years. How does the series address the tension between your hopes for her and your fears of inevitable wounds?

JM: I hope she feels a deep enough connection with us—and enough confidence in herself—to put her wounds in perspective. Only time will tell what memories will stick. I wanted proof of how much love we share. But I also worry about the outside messages girls receive—from media, advertising, even politics—about women’s lives and bodies. My own early years were shaped negatively by being female. I don’t want her caught in the same web, so I made photographs that wrestle with that tension, including images about the overwhelming pinkness of childhood.

Q: The images in How Easily We Are Undone hold space for loss, surrender, and transformation. Do you see it as a closed chapter of motherhood or as part of an ongoing meditation on identity and love?

JM: Honestly, I don’t know. All of my work circles back to identity—how and why we believe the things we do about ourselves. Motherhood has shown me that identity is constantly shifting. Just as I get comfortable with one, a new one takes its place. Looking back, I see that I’ve been doing this my whole life. Motherhood simply made that process more visible.

Q: Finally, did being recognized as a Critical Mass Top 50 artist create opportunities for you—either immediately or over time?

JM: Nothing happened right away, but over time I was accepted into more shows and invited to participate in more opportunities. I think name and image recognition played a big role. That body of work also demonstrated that I could develop and complete a deeply personal project, which led me to start teaching workshops on that subject. In the long run, Critical Mass gave my career a real boost.

JP Terlizzi 2018

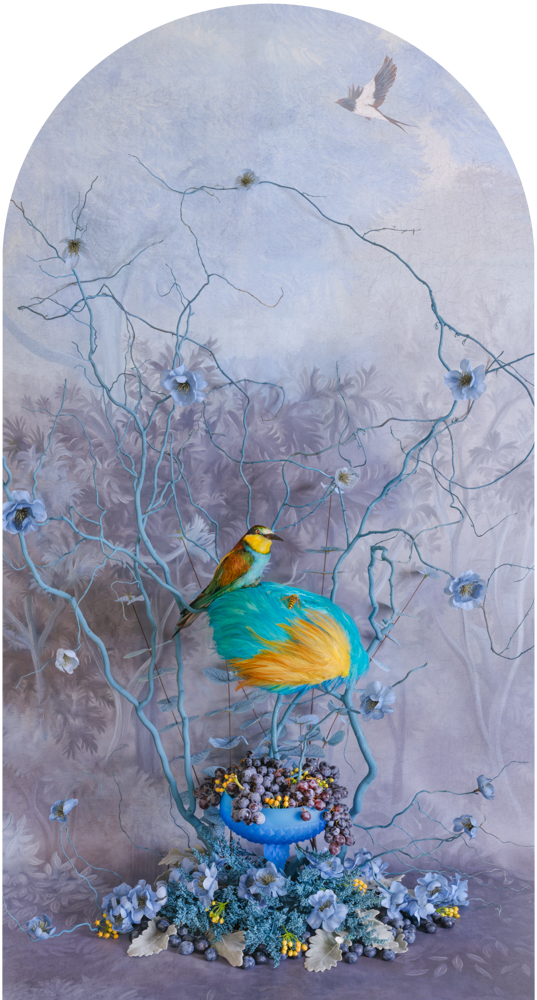

With his series Descendants and Sanctuary of the Winged, photographer JP Terlizzi weaves memory, material, and metaphor into deeply personal explorations of family, legacy, and identity. Whether embedding his own blood specimens into portraits of his loved ones or framing birds within arches that echo ritual and sanctuary, Terlizzi’s work is both intimate and expansive—tethered to his own history yet resonant with universal questions of belonging. A four-time Critical Mass Top 50 finalist, he reflects on grief, estrangement, and inheritance, while also tracing parallels between human ritual and avian display. In this conversation, he shares the origins of these projects, the emotional terrain behind them, and how recognition through Critical Mass has shaped his practice and community.

JP Terlizzi ( American, b. 1962 ) is a New York City Metro based photographer whose contemporary practice explores themes of memory, relationship, and identity. His images are rooted in the personal and heavily influenced by the notion of home, legacy, and family. He is curious about how the past relates to and intersects with the present and how the present enlivens the past, shaping one’s identity.

JP’s highly acclaimed still life work is known for its distinctive use of style, pattern, texture, and color. He uses food and objects to explore familial heritage and personal stories, creating visual narratives that connect the past and present. Through his evocative use of composition and symbolism, JP captures not only the physical essence of objects but also their emotional and cultural significance creating images that resonate with personal histories and collective memories.

Born and raised in the farmlands of Central New Jersey, JP earned a BFA in Communication Design at Kutztown University of PA with a concentration in graphic design and advertising. He has studied photography at both the International Center of Photography in New York and Maine Media College in Rockport, ME.

JP’s work has been exhibited extensively in galleries and museums across the United States and abroad, including juried, invitational, and solo exhibitions, notably at Koslov Larsen Gallery, (Houston, TX), Vicki Myhren Gallery (Denver, CO), Gilman Contemporary (Ketchum, ID), Klompching Gallery (Brooklyn, NY) Florida Museum of Photographic Art, Danforth Museum (Framingham, MA), The Griffin Museum of Photography (Winchester, MA), Ft. Wayne Museum of Art (Ft. Wayne, IN), and The Montclair Museum of Art (Montclair, NJ), among others.

JP has been recognized four times in Photolucida’s Critical Mass Top 50 and three times as a Finalist. His work has appeared in AIPAD, The Photoville Fence, and his portfolios have won notable awards of distinction with Klompching Gallery (Brooklyn, NY), Sohn Fine Art Gallery (Lenox, MA), and Soho Photo Gallery (New York, NY).

Print and online publications include: PDN, National Geographic, Shots Magazine, Yogurt Magazine (Italy), Art Market Magazine, (Israel), Lens Magazine (Israel), Photographer’s Companion (China), Abridged Magazine (Ireland), New England Review, Mono Chroma Magazine, Artdoc Magazine, All About Photo, L’oeil de la Photographie, and The Photo Review.

JP’s work is represented in the permanent collections of The Royal Caribbean Group, Fort Wayne Museum of Art, Candela Gallery Acquisitions, in addition to private and corporate collections across the US, Canada, and Internationally.

Instagram: @jpterlizzi

Q: Can you tell us how you first learned about Photolucida’s Critical Mass, and what motivated you to enter?

JPT: I first heard about Critical Mass in 2015 through friends and teachers at the International Center of Photography in New York. At the time, I was new to photography and had just completed my first series, Hunter’s Calling, which documented young men during hunting season. I remember feeling both inspired and intimidated by the caliber of past recipients, and I wasn’t yet confident in writing about my own work. I had just started entering juried competitions, but I decided to take a leap and submit to Critical Mass as well

Q: What was the genesis of your 2018 Critical Mass Top 50 portfolio Descendants, and how long did you work on the project?

JPT: Descendants grew from my desire to honor the memory and love I carry for my maternal family, as well as the deep connection I shared with my mother’s siblings, who each helped shape who I am. At first, I created the series for myself—simply to have photographs of my family that were truly my own. I never imagined sharing them publicly. I began in 2017 and completed the initial work in 2020, featuring portraits of my two adult sons and me. In 2024, I added a portrait of my three-year-old grandson, and I plan to continue expanding the series as future generations arrive. Ultimately, Descendants is a personal legacy—an archive of love, memory, and even a touch of the macabre—leaving my children and grandchildren a lasting, if unusual, heirloom of my blood.

Q: By incorporating your own blood specimens through microscopic slides onto the portraits, how did you intend to transform the viewer’s perception of ancestry and identity?

JPT: Using my own blood specimens allowed me to create a physical, tangible bond with the archive. Blood is the most intimate marker of lineage—it carries memory, genetics, and history. By placing it directly onto the portraits, they became more than images; they became living archives, tying me physically to generations before and after me. My intention was for viewers to consider identity not only as cultural or visual inheritance, but also as something biological and visceral—a reminder that ancestry flows through blood as much as it does through memory and tradition.

Q: Can you describe the emotional journey that led to creating Descendants, particularly in light of personal loss and familial estrangement?

JPT: I come from a very large extended Italian family, but I never had a relationship with my father or most of his relatives. My mother’s side, however, was my anchor. Over four years, I lost nine of my maternal aunts and uncles. I also had no family photographs to call my own—my brother destroyed them in front of me while our mother was dying. Descendants became a way to process this grief, reclaim memory and connection, and preserve the legacy of the family who shaped me.

My aunts, uncles, and cousins gave me a sense of belonging, especially as I was estranged from my mother and brother for decades. Photographs are direct links to memory; they allow us to slow down, reflect, and connect. Holding an image of a loved one creates profound intimacy, letting memory resurface in tender and transformative ways. Descendants became my space for remembrance, reverence, and love—a personal archive connecting me to generations past.

Q: You describe the bird as “more than a subject—a metaphor.” What aspects of human adaptation or self-expression were you hoping to illuminate through this parallel between bird behavior and human ritual?

JPT: Birds build, adorn, and perform in ways that mirror our own rituals—how we decorate our homes, dress ourselves, or mark important milestones. By drawing that parallel, I wanted to show how much of human life is also about adaptation and display. We gather materials, shape environments, and use ritual and adornment to express identity and connect with others. Through the metaphor of the bird, we glimpse our own instincts—our need for sanctuary, expression, and survival.

Q: The arch recurs as both a framing device and a metaphor for sanctuary, passage, and protection. How does this motif contribute to the sense of transformation or transcendence within the series?

JPT: The arch works as a threshold—a point of entry or passage. By placing birds and their nests within it, I wanted to suggest movement from one state to another: from vulnerability to protection, or from the ordinary into something contemplative. The arch is more than a frame—it creates a space of transcendence, inviting both subject and viewer into sanctuary.

Q: The images suggest identity is shaped by material, context, and adaptation, mirroring ecological processes. Do you view this project as a broader commentary on how humans, like birds, gather and display what they need to survive, resist, or belong?

JPT: Absolutely. While going through the end of a long-term relationship, I began reimagining my home and reconsidering the objects I had collected. I realized those choices reflect my identity. That shift sparked Sanctuary of the Winged, which is still ongoing. Just as birds construct nests shaped by need and personality, we build homes that embody our tastes, values, and memories. The objects we choose and the rituals we enact within those spaces become extensions of who we are. Like birds, we use our environments not just to survive but to connect, communicate, and define ourselves.

Q: Finally, how did recognition as a Critical Mass Top 50 artist impact your career, both immediately and in the longer term?

JPT: Being recognized four times as a Critical Mass Top 50 artist is an incredible honor. It’s validating to know my work is seen by over 200 industry professionals. While it hasn’t dramatically altered the trajectory of my career, it has raised awareness of my work and introduced it to wider audiences.

More importantly, it has strengthened my voice. I’ve become more confident in articulating my ideas, writing about my projects, and speaking about them publicly. It’s also allowed me to support other artists entering Critical Mass. The sense of community within the program is unmatched, and I’m grateful to be both a recipient and a contributor.

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

Arnold Newman Prize: C. Rose Smith: Scenes of Self: Redressing PatriarchyNovember 24th, 2025

-

Celebrating 20 Years of Critical Mass: Cathy Cone (2023) and Takeisha Jefferson (2024)October 1st, 2025

-

Celebrating 20 Years of Critical Mass: George Nobechi (2021) and Ingrid Weyland (2022)September 30th, 2025

-

Celebrating 20 Years of Critical Mass: Amy Friend (2019) and Andrew Feiler (2020)September 29th, 2025

-

Celebrating 20 Years of Critical Mass: Jennifer McClure (2017) and JP Terlizzi (2018)September 28th, 2025