Celebrating 20 Years of Critical Mass: Amy Friend (2019) and Andrew Feiler (2020)

Photolucida is a Portland-based nonprofit dedicated to providing platforms that expand, inspire, educate, and connect the national and international photography community. Critical Mass, Photolucida’s annual online program, is designed to foster meaningful connections in the photography world. Open to photographers at all levels, anywhere in the world, participants submit a portfolio of 10 images. Following an initial pre-screening, 200 finalists are selected to have their work reviewed and voted on by up to 200 distinguished international photography professionals. From this process, the Top 50 are chosen, and a range of awards is presented. Submissions open each June.

In 2025, we celebrate the twentieth year of announcing the Critical Mass Top 50 finalists! We are honored to partner with Lenscratch to reflect on this history through a special series highlighting two artists from two different years in each post. Each featured artist offers a window into the diversity of projects and voices that make up Critical Mass—from documentary and narrative photography to conceptual, photo-based practices. These Q&As share the history, intention, and trajectory of the artists, pairing their Critical Mass portfolios with newer work.

For Critical Mass 2025, we received submissions from artists across 26 countries, tackling subjects in countless styles—from black-and-white and digital photography to chemigrams, cyanotypes, photographic sculpture, and textiles. Our esteemed jurors, representing a wide range of global perspectives, dedicate their expertise and thoughtful consideration to this process, often leaving feedback and encouragement for the artists.

Critical Mass continues to elevate emerging photographers, providing a platform that amplifies their voices to broader audiences and to the industry professionals who help shape careers. We are deeply grateful to everyone who makes this possible.

Amy Friend 2019

In her practice, Amy Friend pushes the boundaries of what a photograph can hold—transforming images into sites of rupture, resonance, and reimagining. Through series such as Multi-Verse and Tiny Tears Fill an Ocean, she layers vernacular and personal photographs, immerses prints in seawater, and embraces processes of tearing, overlaying, and crystalizing. The results are images that shimmer between beauty and fracture, presence and absence, memory and possibility. Selected as a 2019 Photolucida Critical Mass Top 50 artist, her work invites viewers to consider how histories overlap, how the personal is always entangled with the global, and how photography itself can serve as both archive and portal.

Amy Friend is an award-winning Canadian artist working through photography, installation, and community-based collaborations. Her process-driven practice explores personal and collective histories, time, land-memory, oceans, dust, and our connections to the universe. Friend’s work has been exhibited nationally and internationally in major exhibitions, festivals, and institutions including the Bibliothèque Nationale de France (Paris), incamera galerie (France), Paris Photo, Meymac Centre d’art contemporain (France), Gexto Photofestival (Spain), DongGang Photography Museum (South Korea), Onassis Cultural Centre (Greece), GuatePhoto (Guatemala), Encontros da Imagem (Portugal), Alzueta Gallery (Spain), Photoville (New York), Museum London (Canada), Rodman Hall (Canada), and Abbaye de Silvacane (France). Her work has appeared in The New York Times Magazine, Time, California Sunday

Magazine, GUP (Amsterdam), EKI(Italy), LUX (Poland), and The Walrus (Canada). Friend was selected for the 2019 Taylor Wessing Portrait Prize at the National Portrait Gallery (London, UK) and is a multiple Top 50 finalist and the 2014 winner of Critical Mass. She also exhibited in Elles X at Paris Photo 2018. Friend is currently creating new work with support from the Ontario Arts Council and is working with L’ Artiere Publishign on a new monograph set for release in the Autumn of 2025. Amy Friend is a Canadian artist working with various methodologies through photography, installation, and community based collaborations. Friend’s process driven work has been included in national and international exhibitions, projects and festivals including, Gexto Photofestival (Spain), Paris Photo, incamera galerie (France), Museum London (Canada), Onassis Cultural Center (Greece), ASPA (Sardinia), DongGang Photography Museum (South Korea), GuatePhoto (Guatemala), Mosteiro de Tibães at the Encontros Da Imagem (Portugal), Rodman Hall (Canada), Photoville (New York, USA), National Portrait Gallery, (UK), and at the Abbaye De Silvacane, La Roque D’Antheron (France).

Friend is an Associate Professor of Visual Arts at Brock University, Niagara, Canada.

Instagram @amyquerin

Q: How did you first learn about Photolucida’s Critical Mass, and what inspired you to enter?

AF: I first learned about Photolucida’s Critical Mass through colleagues and fellow photographers who spoke highly of the opportunity to share work with an international community of creative professionals. What struck me was the nature of the platform: submitting a body of work to such a broad jury allowed for unexpected dialogues and connections to unfold. I was inspired to enter because I wanted to engage with those possibilities. Critical Mass offered a way to test how my work might be received in a wider conversation. I also didn’t give up—I applied several times before reaching the Top 50. That persistence taught me a great deal about how to re-examine and refine my work.

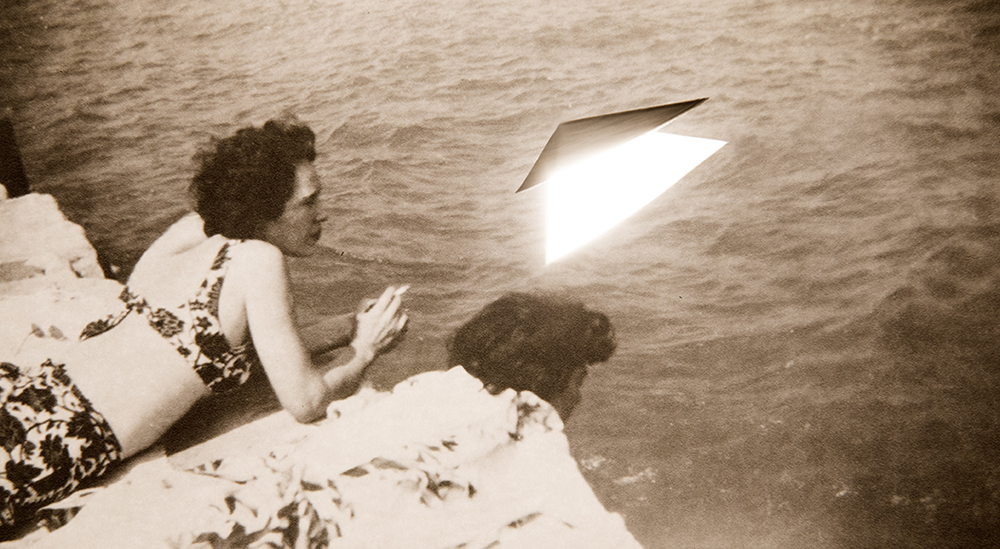

Q: Your 2019 Critical Mass Top 50 series Multi-Verse merges vernacular photographs with your own imagery, creating striking disjunctions across time and space. How do you see this layering of sources connecting to the concept of parallel universes?

AF: When I began Multi-Verse, I was curious about what unfolds when seemingly unrelated moments—vernacular photographs from unknown lives and my own images—are placed in dialogue. Though drawn from different times and geographies, when layered together they suggest simultaneity: multiple realities existing at once or repeating over time.

In physics, the multiverse points to parallel worlds unfolding alongside our own. In my practice, the photograph becomes a site where layered histories and imagined trajectories briefly converge. For example, in Wayfinding in Cold Light, an image of a young person emerging from water is split by a seam of searing white light. That light acts like a rupture—it both obscures and reveals, suggesting another dimension breaking through the surface. It becomes a metaphor for how fragile our sense of a singular reality really is, and how narrow our understanding of images can be.

So, the series is less about illustrating science and more about dwelling in poetic resonance. We live surrounded by ghosts of parallel lives, paths not taken, histories forgotten, images misplaced. By layering sources and puncturing their surfaces, I want viewers to sense that what seems fixed may actually be porous: a photograph as both an archive of one reality and a window into countless others.

Q: You’ve said that environmental destruction, political turmoil, and human rights issues influenced your approach to the work. In what ways did those global realities shape the emotional undercurrents of Multi-Verse?

AF: The project began quietly—with my own images and vernacular photographs depicting domestic life, moments of peace, joy, and ordinary family events. But as I continued, reflecting on the turbulence of the world around me, I felt compelled to bring tension into the work. I wanted the images to carry an undercurrent that reminded me these “everyday” moments are always lived against a backdrop of rupture.

For instance, images of floodwaters, soldiers, or children separated from families place serenity beside chaos and injustice. The manipulation of the photos—tears, rips, slivers of light, overlays—became ways to signal darker realities: violence, displacement, the urgency of climate disaster. They aren’t literal documents, but emotional gestures—wounds on the surface pointing to what we often ignore.

In Waters Rising, vernacular photographs of floods became a basis for tearing and cutting, echoing the force of water overwhelming land and reflecting the psychological violence of environmental collapse. Ultimately, these global forces gave the series its duality: the longing for stability versus the reality of fracture. The tension asks viewers not just to look, but to feel implicated—to reflect on what is at stake in our shared moment.

Q: The altered surfaces and luminous effects in the images create powerful disruptions. How do these visual choices speak to what’s unseen or invisible—almost as if evoking other dimensions?

AF: I deliberately disrupt the fixedness of the image. These interventions open the photograph to multiple readings, suggesting that what we see is never the whole story. The luminous effects act like thresholds, pointing toward unseen layers of memory, imagination, or alternate realities that exist alongside the one captured in the frame.

In this way, the photographs become porous. They no longer seal time into a single moment but vibrate with the possibility of other dimensions—spiritual, emotional, or speculative. The ruptures and glows imply energies or presences that cannot be pictured directly but can be felt. They visually acknowledge mystery, the unknown, and the invisible threads connecting us across generations and geographies.

For me, these choices resonate with the metaphor of the multiverse itself: many realities coexisting and brushing against each other. By altering the surface of a single photograph, I remind viewers that what is visible is only a fragment, and that beyond the material plane lies a constellation of other possible worlds.

Q: By separating the word “multiverse” into “multi-verse,” you invite the idea of multiple stories or entry points into the work. What kinds of narratives do you hope viewers might discover when engaging with these photographs?

AF: Separating multiverse into multi-verse opened the word’s potential. It could hold not only a cosmological idea of parallel universes but also a poetic sense of verses—stanzas, songs, or stories. Each photograph becomes its own verse; together they form a chorus of many voices, layered and sometimes discordant, but always in relation.

Our identities, histories, and memories are never singular—they overlap, contradict, and expand. At a time when the world emphasizes fracture—political, cultural, environmental—I want this work to suggest connection. The ruptures, luminous disruptions, and collaging of photographs acknowledge difference but also allow for overlap, like the edges of one world brushing against another.

The narratives I hope viewers find are not prescriptive. I hope the images act as mirrors or portals, reflecting back their own histories. Someone may see an echo of a grandmother’s gestures, another may sense displacement or loss, and another may feel possibility shimmering. Multi-verse is about holding contradictions without erasing them, and recognizing both the gaps and the bridges. To me, that recognition is a quiet but radical act: embracing difference while sensing our place together in the vastness of being.

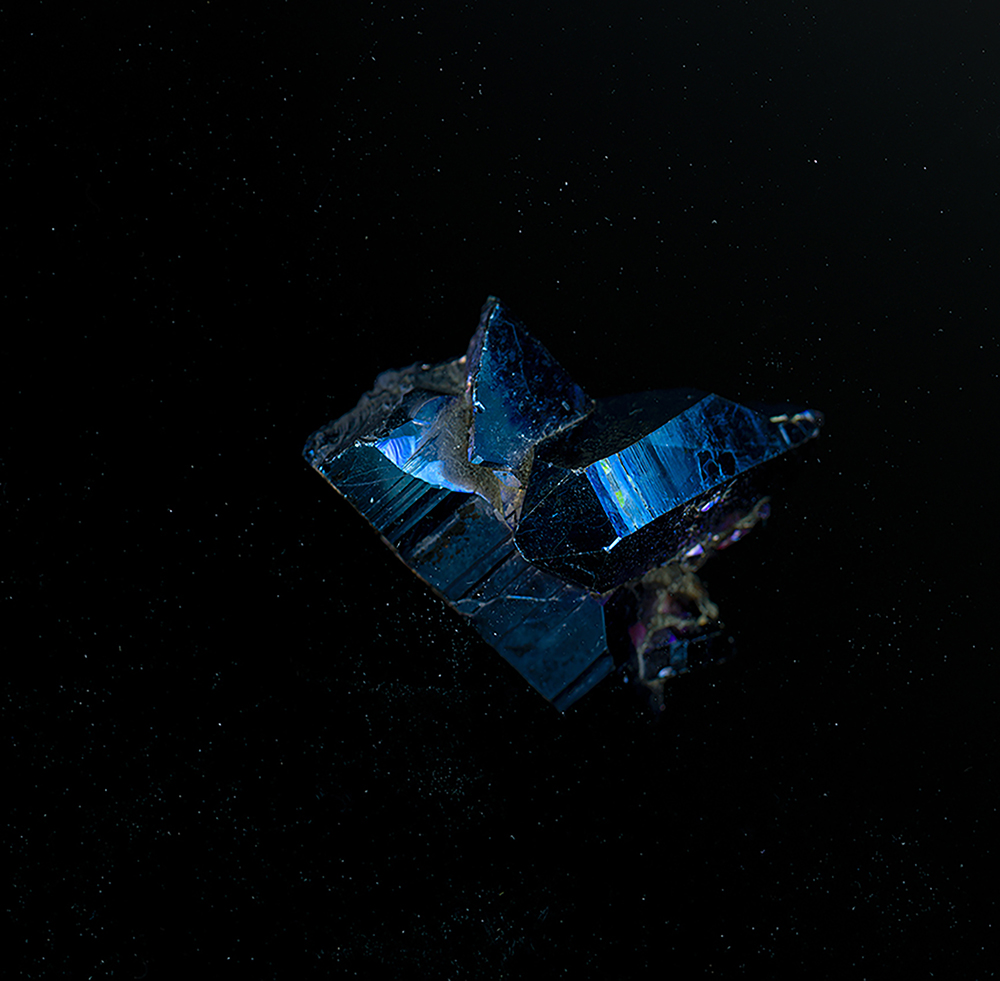

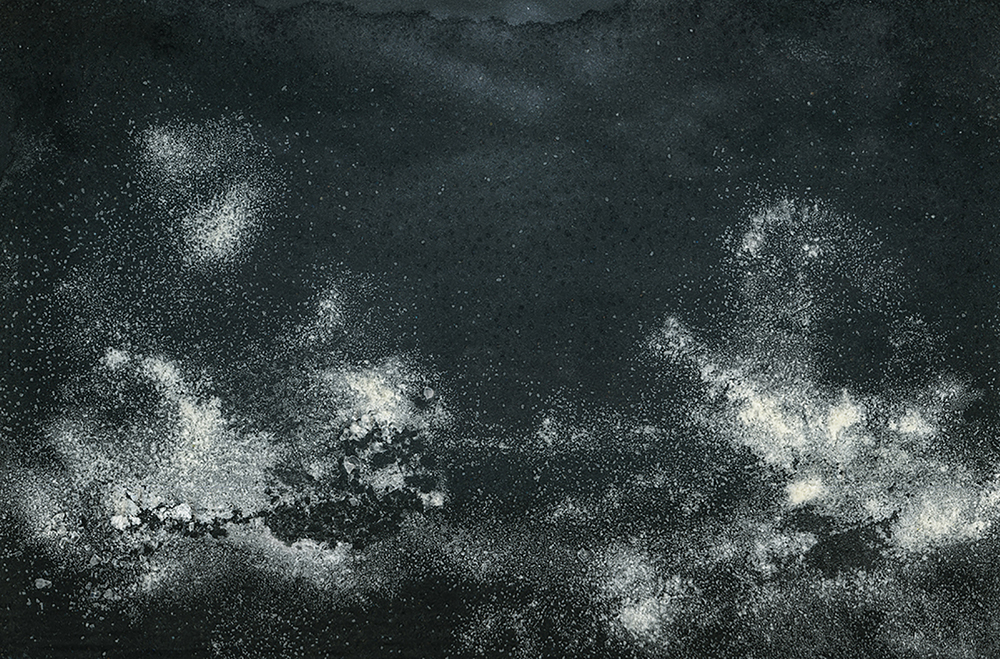

Q: Your long-term project Tiny Tears Fill an Ocean has unfolded over more than two decades across different parts of the world, yet the images feel universal—as though they could belong anywhere. How has your perspective evolved as you’ve returned to the series over time?

AF: When I began photographing bodies of water in my early twenties, I was drawn to their beauty and mystery—the shifting light, endless horizons, the sense of standing at a threshold between worlds. At first, the images felt like private meditations, notes to myself about place and stillness.

During COVID, the project evolved profoundly. Staying close to home, I revisited my archives. Those stored images became a way to grieve collective and individual losses, to process uncertainty. Immersing the photographs in seawater and letting salt crystals etch into the surfaces mirrored that fragility. The sea became a collaborator, transforming the work from static documentation into something ephemeral, alchemical, and alive.

Over decades, my perspective deepened. Water erases and remembers, destroys and renews. That duality mirrors human experience—our griefs, joys, and transformations. What began as an intuitive practice has become an exploration of our bond with the natural world, and how those bonds reveal both fragility and resilience. Tiny Tears Fill an Ocean has become less about a single journey and more about interconnected journeys. However different our lives and losses, we all stand on the same shores, looking across the same waters, asking the same questions of endurance and belonging.

Q: You submerge photographs in seawater, allowing salt crystals to form on their surfaces. What draws you to this delicate process, and how does it transform the way we experience the original seascapes?

AF: Submerging prints in seawater extends my curiosity about photography as a living, luminous material—an image in flux rather than fixed. As the water dries, salt crystals form, inscribing time, place, and matter into the photograph. The resulting images resemble fragile shorelines, sites where creation and erosion converge.

This transformation shifts the seascapes from representation to encounter. The salt interrupts smooth looking; it slows the viewer down, asking them to notice how light catches differently hour by hour. Because salt binds both oceans and bodies—our sweat, our tears—the crystals carry an embodied empathy. They echo our shared salinity and the fragility of marine ecologies. In that way, the work holds what has always drawn me to photography: its ability to bind the luminous with the vulnerable, to make the invisible—time, touch, loss—materially present.

Q: The images are meditative and beautiful, yet they also quietly reference ecological change and rising sea levels. How do you navigate the balance between aesthetic beauty and the urgency of environmental concern in this work?

AF: What compels me about working with the sea is that it refuses to be only one thing. It is beauty and threat at once. When I submerge a photograph, the resulting salt crystals are luminous and delicate, yet they also signal erosion and transformation in our oceans.

Holding these contradictions together feels essential. I don’t want to lecture through the work but to invite viewers into a space where beauty and fragility coexist. The sea leaves its own marks—sometimes subtle veils of salt, sometimes corrosive scars—and that unpredictability embodies both wonder and warning.

By presenting images that shimmer and seduce, I hope they also slow viewers down long enough to sense the undertow of ecological precarity. It’s less about illustrating catastrophe and more about cultivating awareness—that what we most cherish is also what we most stand to lose.

Q: Finally, what impact did being recognized as a Critical Mass Top 50 artist have on your career—both immediately and in the long term?

AF: Being named to the Critical Mass Top 50 was an incredibly important moment for me, both personally and professionally. Immediately, it brought visibility and allowed me to share my work with curators, publishers, artists, writers, and institutions I might never have reached otherwise. That exposure led to invitations for exhibitions, publications, and conversations that placed my projects in a broader international dialogue.

In the longer term, the recognition affirmed that my quiet, process-driven way of working resonated more widely. It built confidence in following threads of my practice—even when unconventional—and continues to open doors. Critical Mass became a kind of bridge, connecting my work to a global community and rippling outward in ways I couldn’t have anticipated.

Andrew Feiler 2020

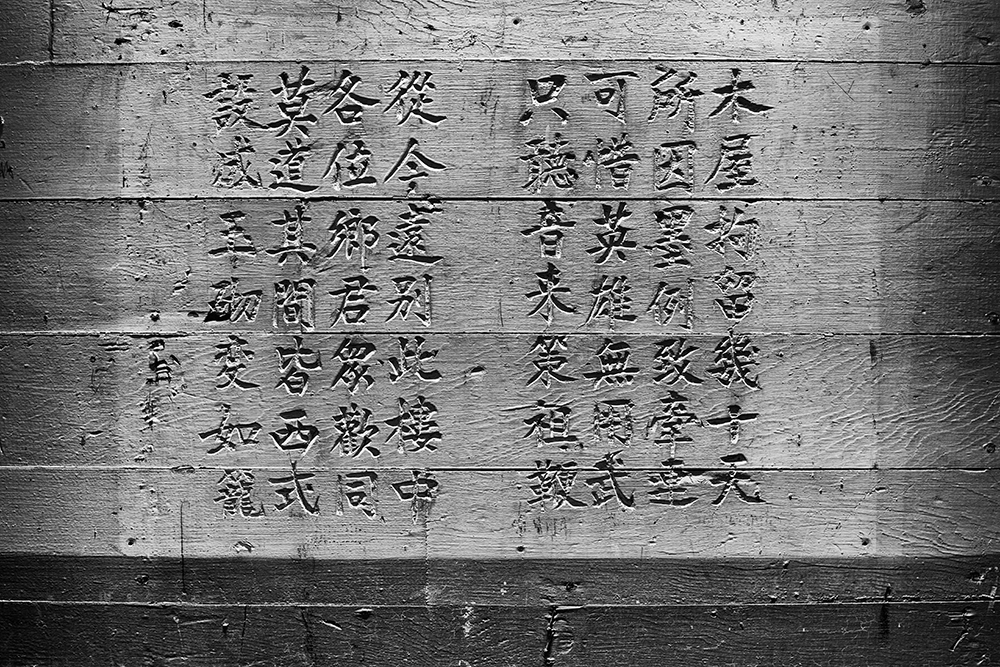

In A Better Life for Their Children, photographer Andrew Feiler documents the untold story of the Rosenwald schools—nearly 5,000 community-built schools that transformed education for African American children in the segregated South. Over three and a half years and 25,000 miles, Feiler photographed 105 surviving sites, weaving together architecture, portraits, and history. His work not only preserves this vital legacy but also highlights the enduring power of civic engagement and collective action.

Andrew Feiler is a photographer and author and fifth generation Georgian. Having grown up Jewish in Savannah, he has been shaped by the rich complexities of the American South. Feiler has long been active in civic life. He has helped create over a dozen community initiatives, serves on multiple not-for-profit boards, and is an active advisor to numerous elected officials and political candidates. His art is an extension of his civic values.

Feiler’s newest book of photography, A Better Life for Their Children: Julius Rosenwald, Booker T. Washington, and the 4,978 Schools that Changed America, was published in 2021 by the University of Georgia Press. This work is the first comprehensive photodocumentary of the program created by Tuskegee Institute principal Booker T. Washington and Sears, Roebuck & Company president Julius Rosenwald. From 1912 to 1937, this collaboration built 4,978 schools for African American children across 15 southern and border states and transformed America. The book is in its third printing.

Feiler was named “Book Photographer of the Year” by Prix de la Photographie Paris in 2022 for A Better Life for Their Children. The book also won the Prix de la Photographie Paris 2022 gold medal for documentary book as well as the International Photography Awards 2022 first place for documentary book. It has been honored with a BarTur Photography Award, an Eric Hoffer Book Award, and a Book, Jacket, and Journal Award from the Association of University Presses. Photolucida named Feiler’s Rosenwald school images a 2020 Top 50 portfolio and Photoville selected them for the 2020 edition of The Fence, an outdoor exhibition displayed internationally in eleven cities. The solo exhibition of this work is now on tour.

Feiler’s earlier book, Without Regard to Sex, Race, or Color, was also published by the University of Georgia Press. Focused on the largely abandoned campus of an historically black college, this body of artistic documentary photography offers a new way into the debate raging in our society about the essential role education has played as the foundation of the American Dream.

Feiler’s photographs have been instrumental in the campaign to create a new US national historical park and inspired the composition of a symphony. His work has been featured in the Wall Street Journal, Smithsonian, The Atlantic, L’Œil de la Photographie, Architect, Preservation, The Forward as well as on CBS This Morning, PBS, and NPR. His prints have been displayed in galleries and museums including solo exhibitions at such venues as the National Civil Rights Museum at the Lorraine Motel in Memphis, National Center for Civil and Human Rights in Atlanta, and International Civil Rights Center & Museum in Greensboro, North Carolina. His photographs are in public and private collections including that of the Library of Congress and the Smithsonian Institution’s National Portrait Gallery.

Feiler earned his bachelor’s in economics from The Wharton School of the University of Pennsylvania. He earned a master’s in modern history from Oxford University and a master’s in business administration from Stanford University.

Instagram: @andrew.feiler

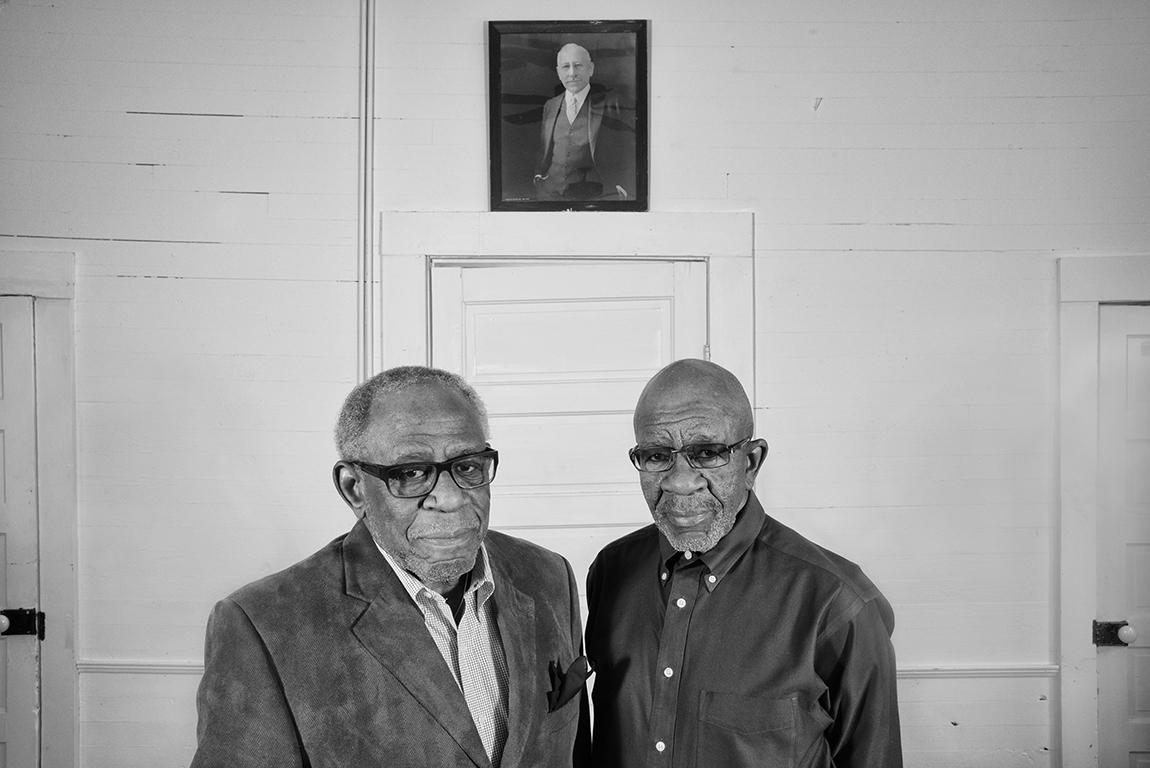

©Andrew Feiler, Elroy & Sophia Williams – Sophia Williams’ Grandparents, Formerly Enslaved, Acquired and Donated Land for a Rosenwald School

Q: How did you first learn about Photolucida’s Critical Mass, and what inspired you to enter?

AF: This project is the first comprehensive photodocumentary of the program created by Tuskegee Institute principal Booker T. Washington and Sears, Roebuck & Company president Julius Rosenwald. Beginning in 1912, they partnered with Black communities across the segregated South to build public schools for African American children. Over 25 years, 4,978 schools were built across fifteen states, dramatically improving Black educational attainment and shaping the generation who became leaders and foot soldiers of the civil rights movement.

After driving 25,000 miles over three and a half years, I turned this work into my publisher in 2020 for the book that would be released in 2021. At the time, I had no idea how these images and stories would resonate. Submitting to Critical Mass was an act of putting myself out there—seeing what would happen. Being named a Top 50 finalist was the first recognition this body of work received, and it became a powerful early endorsement.

©Andrew Feiler, Frank Brinkley & Charles Brinkley, Sr. – Educators, Brothers, Rosenwald School Former Students

Q: In your 2020 Critical Mass Top 50 portfolio A Better Life for Their Children, you photographed 105 Rosenwald schools across 15 states. How did you decide which schools to include, and what guided your choice to document both restored and unrestored sites?

AF: At the outset, it wasn’t clear how to tell this story visually. I drew inspiration from other photographers—Bernd and Hilla Becher’s austere studies of architecture, William Christenberry’s southern vernacular, and Andrew Freeman’s documentation of Manzanar. I initially focused on exteriors and the architectural arc of the Rosenwald program, which evolved from modest wooden one-teacher buildings to multi-story brick schools. But that story alone felt incomplete.

Of the original nearly 5,000 schools, only about 500 survive, and just half of those have been restored. The urgency of preservation became central to my narrative. To tell it, I had to gain access to the interiors—where I met extraordinary people who had attended or taught in these schools, and those devoting their lives to saving them. The portraits I created in those encounters became the most emotionally rewarding part of the project.

Q: Your photographs are paired with narratives drawn from research and interviews. How did you navigate the balance between visual storytelling and the historical and personal voices you uncovered?

AF: My process is research-driven, with reading and photography informing one another. The deeper I dug, the more extraordinary stories I uncovered: a school in Oklahoma tied to the displacement of enslaved African Americans along the Trail of Tears; a Mississippi school built despite state-level embezzlement of Rosenwald funds; a Tuskegee Airman alumnus who revealed how the Rosenwald Fund helped launch that legendary program.

Over time, I realized that what I uniquely bring to photography is this pairing of image with deeply researched story. I came to love the research and writing as much as the photography itself.

Q: Many former students and teachers of Rosenwald schools went on to play pivotal roles in the civil rights movement. How did listening to their stories influence your understanding of the schools’ broader legacy?

AF: The impact crystallized when I met two economists at the Federal Reserve Bank of Chicago who had studied Rosenwald schools. Their data shows that between World War I and World War II, the persistent Black-white education gap in the South narrowed significantly—and Rosenwald schools were the single most important factor.

Beyond statistics, these schools educated many who would transform America: Medgar Evers, Maya Angelou, members of the Little Rock Nine, and Congressman John Lewis. Both Lewis and one of the Little Rock Nine are in my book, with Lewis contributing the foreword. Meeting former students, teachers, and preservationists underscored just how transformative this program was. Rosenwald alumni became teachers, farmers, preachers, businesspeople—the backbone of a rising African American middle class.

Q: Growing up Jewish in Savannah and later becoming deeply engaged in civic life, how have the complexities of the American South shaped both your artistic voice and your commitment to social issues through photography?

AF: I’ve been a serious photographer most of my life, freelancing in high school and later making images while traveling. About a decade ago, I made the pivot to take my work—and myself as an artist—more seriously. That meant finding my voice.

I’ve always been deeply engaged in civic life—helping launch over a dozen community initiatives, serving on nonprofit boards, and advising civic leaders. I found that the subjects I was drawn to photograph were natural extensions of my civic commitments. My art became another form of civic voice.

©Andrew Feiler, 1865 General William T. Sherman’s Former Office, Green-Meldrim House, Savannah, Georgia

Q: The Rosenwald program represents one of the earliest collaborations between Jewish and African American communities in the South. As a Jewish Georgian yourself, how did your identity shape the way you approached this history through photography?

AF: I first heard of Rosenwald schools in 2015 from a preservationist. I was stunned: how had I never heard of them? I’m a fifth-generation Jewish Georgian, and the pillars of this story—southern, Jewish, activist—are the pillars of my own life. That deep personal resonance made me embrace the story wholeheartedly.

Q: In documenting these schools, you not only captured architecture but also the resilience of the communities that built and sustained them. What do you hope contemporary audiences take away about the power of civic engagement?

AF: I come to this work as an activist. Think of Washington and Rosenwald in 1912—launching a school-building program for African American children in the segregated South. That was both optimistic and visionary, a deeply multigenerational act.

I often recall Congressman Lewis, who contributed to my book. Despite all he endured, his mantra remained: “Be hopeful. Be optimistic. Our work is not the work of a day, a week, a month, or a year. It is the work of a lifetime.” Those words continue to guide me.

Q: Your photographs have not only documented history but also contributed to it—helping inspire a national historical park and even a symphony. How do you see the role of photography as a catalyst for civic engagement and cultural change?

AF: There’s a saying: “Don’t know much about history.” Yet history matters enormously. It teaches us about moral failures and moral growth, regress and progress. Today, when some voices seek to distort history, photography can invite audiences into these essential stories.

The historian Stephen Ambrose once said that the secret to teaching history lies in the last five letters of the word itself: story. Photography is uniquely powerful at amplifying history and making its lessons resonate.

Q: With degrees in economics, modern history, and business, your academic background is unusually diverse for an artist. How have these disciplines influenced the way you approach documentary photography and the stories you choose to tell?

AF: My wide-ranging background shapes both the subjects I pursue and the way I amplify them. Books anchor my projects, but exhibitions vastly expand their reach. My previous book traveled for four and a half years to nine venues. The Rosenwald project premiered at the National Center for Civil and Human Rights in Atlanta in 2021, has already traveled to ten venues, and is booked into 2027.

I also give talks—over 90 so far—on topics from Black education to southern Jewish history to preservation. This combination of scholarship, photography, and public engagement ensures the work reaches audiences far beyond the page.

Q: Finally, what impact did being recognized as a Critical Mass Top 50 artist have on your career—both immediately and in the long term?

AF: Selection as a Critical Mass Top 50 artist was transformative. It was the first recognition for this body of work and catalyzed extraordinary opportunities. My book, A Better Life for Their Children: Julius Rosenwald, Booker T. Washington, and the 4,978 Schools that Changed America (University of Georgia Press, 2021), was featured in the Wall Street Journal, Smithsonian, L’Œil de la Photographie, CBS, PBS, and NPR. It earned multiple international awards, and prints entered the collections of the Library of Congress and the Smithsonian’s National Portrait Gallery.

All of this has given me what I call “cultural capital.” Unlike politicians who hoard political capital, I intend to spend mine—on new projects that continue to explore how we tell the American story. That wellspring of credibility began with Critical Mass.

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

Greg Constantine: 7 Doors: An American GulagJanuary 17th, 2026

-

Yorgos Efthymiadis: The James and Audrey Foster Prize 2025 WinnerJanuary 2nd, 2026

-

Arnold Newman Prize: C. Rose Smith: Scenes of Self: Redressing PatriarchyNovember 24th, 2025

-

Celebrating 20 Years of Critical Mass: Cathy Cone (2023) and Takeisha Jefferson (2024)October 1st, 2025

-

Celebrating 20 Years of Critical Mass: George Nobechi (2021) and Ingrid Weyland (2022)September 30th, 2025