The Do Good Fund: Brought to Light

Looking at Slow Exposure Exhibitions…

©Debbie Fleming Caffrey, Harry’s Hands

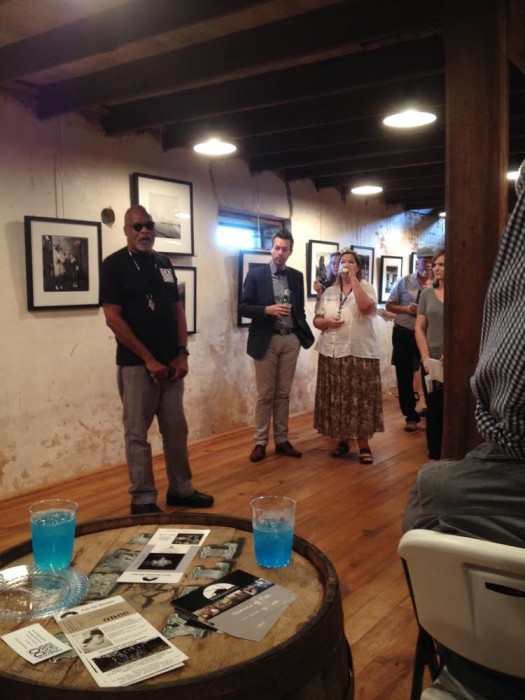

An exhibition that was one of the highlights of the SlowExposures Festival was Brought to Light, presented by the Do Good Fund at the Whiskey Bonding Barn and curated by Constance Lewis. Today we are showing select images from the exhibition and the collection, but the entire collection will be on exhibit at the Lamar Dodd Art Center at LaGrange College, LaGrange, GA October 6-December 19, 2014. President Alan Rothschild is a terrific ambassador to Southern photography and I thought I would ask him a few questions about the Do Good Fund.

The Do Good Fund, Inc. is a public charity based in Columbus, Georgia. Since its founding in 2012, the Fund has focused on building a museum-quality collection of contemporary Southern photography, including works by emerging photographers.Do Good’s mission is to make these works broadly accessible through regional museums, nonprofit galleries and nontraditional venues, and to encourage complimentary, community-based programming to accompany each exhibition.

©Pam Pecchio, Mitchell’s Arm

Tell us a little bit about your background and what brought you to your interest in photography.

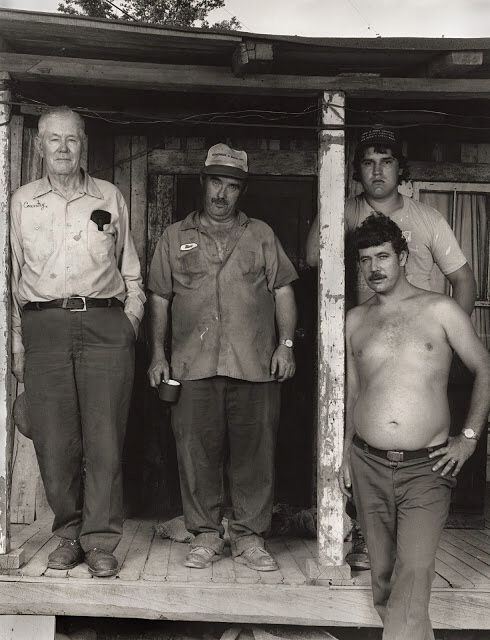

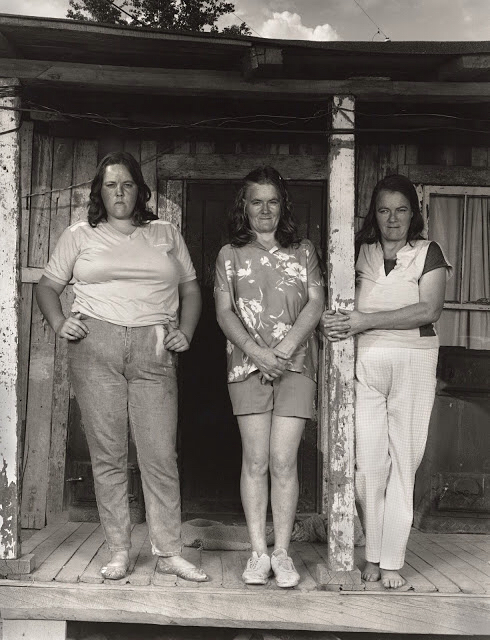

I am a native of Columbus, Georgia, a small, but culturally-rich, city on the eastern edge of the Black Belt. My introduction to Walker Evans’ photographs in Let Us Now Praise Famous Men came through a high school Southern literature class. I was struck at the time by how much the landscape of rural East Alabama and Southwest Georgia resembled the images taken by Evans forty years earlier. The work by Baldwin Lee, Brandon Thibodeaux and Shelby Lee Adams in the collection suggests that in many parts of the South, little has changed since, despite the population growth in our coastal regions and urban centers.

©Shelby Lee Adams, Lynn Fork Men

©Shelby Lee Adams, Lynn Fork Women

As a history major at the University of Virginia, I found myself absorbing much more information from the images in my history books than from the books’ text. I distinctly remember that a chart showing the number of Civil War casualties by battle had little impact on me, but a single Matthew Brady battlefield image featured in our textbook from brought the horrors of this century-old war fully to the present.

©Brandon Thibodeaux, Christmas Tree, Alligator, MS

The same was true for the New Deal-era photographs. I recall little about the Great Depression from my American history books, but the hardships of the Southern tenant farmer were forever embedded in my memory by Walker Evans’ Hale County, Alabama images accompanying the text. As an aside, I learned much later that Jack Delano, John Vachon and Marion Post Walcott photographed in and around Columbus during the FSA project. In fact, I have a newspaper photograph on my office wall of three generations of my family standing in front of their family business in the early 1900’s. I recently ran across a Walcott image taken in 1940 of almost the exact same spot.

Soon after law school, a friend started a regular gathering on his family’s farm just south of Hale County. Visiting Greensboro and environs during these events had the opposite effect of Brady’s and Evan’s images – instead of bringing history alive through photography, touring Hale and Perry Counties made me appreciate both how much Southern history and culture have been preserved by the photographers of the region, and also the immediacy of this history. Anyone interested in Southern photography can feel this connection coming from the old hotel window where Evans shot his Main Street Greensboro images, or from the Sprott Church and Post Office, both of which stand today as a tangible connection to our past, to Evans and, more recently, to William Christenberry.

©Keith Carter, Garlic

What compels you to purchase particular imagery?

The images in the Do Good Fund collection are not the bone-dry documentary photographs of Matthew Brady or Walker Evans, but the photographs certainly owe something to Brady and Evans. What drew me to the images in the collection is that each is about, rather than just of , something– telling a story in one way or another about the Southern experience. Very often the photograph captures routine occurrences, but in a way that reveals the story of the historic or evolving South, along with a simple beauty that we tend to overlook. My hope is that the photographs touch others in the same way, seeing the images will cause them to pause a bit longer to appreciate the scenes previously taken for granted as mundane or routine, while gaining a deeper understanding of the people and places around us.

How did The Do Good Fund come about?

While I continue to be an avid supporter of museums, in reality, only a very small percentage of works in most museum collections are display at any one time. So, even if you are fortunate enough to live in a community with the vision to have a great museum, and that museum’s collection holds photographic images that interest you, there’s probably only a one or two percent chance the image will be on display when you’d like to see it. The mission of the Do Good Fund is not to collect for collecting sake, but to make its collection of Southern photographs widely available to communities interested in showing the work.

©Susan Worsham, Young Boy Cleaning Church, VA

A question I get asked a lot is how we came up with the name, The Do Good Fund. Sam Mockbee was one of the co-founders of Auburn University’s Architectural Outreach Program called the Rural Studio. The Studio is headquartered in Hale County, which as you know, is the location of many of the images in Let Us Now Praise Famous Men, and, also the place of William Christenberry’s lifelong photographic documentation of decaying houses, stores, and barns.

Mockbee, whose first job was here in Columbus, believed that architects had a greater duty than just to design structures. One of the founding principles of the Rural Studio was Mockbee’s belief that poor people deserve beautiful houses too, and one of his famous exhortations to his departing students was to go and “Do Good.”

©Keith Carter, Chicken Feathers

Just as Mockbee though ordinary folks deserved the dignity of nice house, we, too, think that ordinary folks deserve the respect and attention given to them by the photographers in the collection. Thus, not only was Mockbee’s phrase a catchy one, we thought there was some commonality in our efforts to dignify the people and places of the South that often go unnoticed or underappreciated.

©Brandon Thibodeaux, Birds in Field, Mound Bayou, MS

What’s coming up for the Fund?

We just completed an exhibition at Slow Exposures 2014 and the collection is now on view at LaGrange College, just south of Atlanta, until Mid-December. Next up is a show at East Tennessee State University entitled, Behind the Lens. Since women have historically been the subject of photographs more often than the photographer, the curators of the East Tennessee show want to present images taken exclusively by female photographers working in the South. We are also finalizing details for a quick show in New Orleans during the Society for Photographic Education’s National Conference in March.

©Debbie Fleming Caffrey, Burning Cane at Sunset

© Jeff Rich, Blue Ridge Paper Mill

Perhaps our most exciting news is that we have just selected our inaugural Do Good Fund Photographer-In-Residence, New York photographer, Lauren Henkin. Lauren will spend next May in the Alabama Black Belt producing a series of images for the collection and hosting a summer show of images from the collection in the Black Belt as well.

What part of the process is most fulfilling to you?

We have a special initiative focused on collecting images by young photographers presently working in the South. For example, we acquired two pieces from Jackson, Mississippi photographer Whitten Sabbatini soon after he graduated from Mississippi State in 2013. In an Aint-Bad magazine interview earlier this year, Whitten credited this acquisition for some of the other recognitions he received, including a feature in Jeff Rich’s Oxford American column. Whitten’s first solo show is now up at the Brooks Museum in Memphis. It is very rewarding to watch the younger photographers in the collection successfully pursuing their photographic endeavors.

©Mike Smith, Gray, TN 1996

©Jerry Siegel, Shooter

©Mark Steinmetz, Athens, GA, 1997

© Baldwin Lee, DeFuniak Springs, Florida, 1984

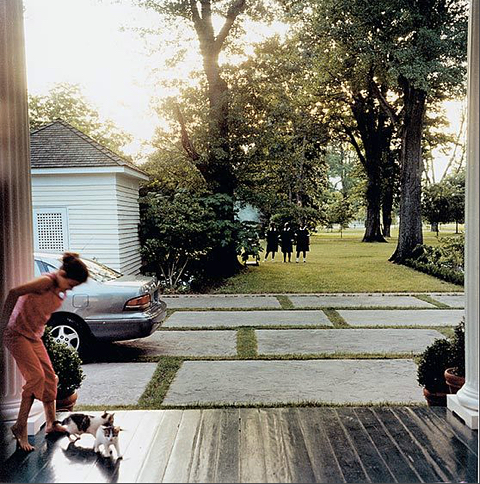

©Maude Shuler Clay, Sophie with Cats

©Baldwin Lee, Shreveport, Louisiana, 1984

All content on this site cannot be reproduced without linking to Lenscratch and without the permission of the photographer.

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

Arnold Newman Prize: C. Rose Smith: Scenes of Self: Redressing PatriarchyNovember 24th, 2025

-

The Aline Smithson Next Generation Award: Emilene OrozcoNovember 21st, 2025

-

MATERNAL LEGACIES: OUR MOTHERS OURSELVES EXHIBITIONNovember 20th, 2025

-

Josh Aronson: Florida BoysNovember 1st, 2025

-

Robert Rauschenberg at Gemini G.E.LOctober 18th, 2025