Ben Huff: The States Project: Alaska

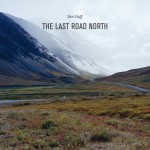

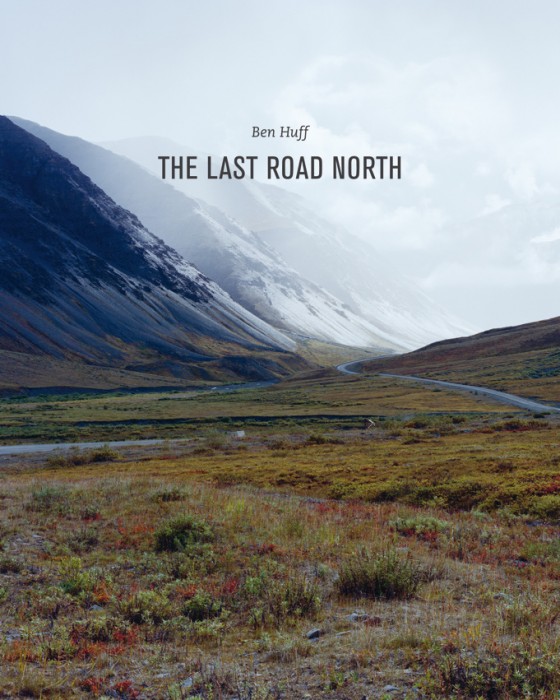

It is with great pleasure that we launch the LENSCRATCH States Project, beginning with the state of Alaska and the wonderful Alaskan Guest Editor, photographer Ben Huff. Today we celebrate Ben’s work and his monograph, The Last Road, published by Kehrer Verlag. Through this project, Ben discovered the complexity of the Alaskan landscape – the physical and psychological line between wilderness and oil. For five years he traveled the road from his home in Fairbanks, and created a “melancholy portrait of a space that asks us to reconsider our perception of frontier”.

It is with great pleasure that we launch the LENSCRATCH States Project, beginning with the state of Alaska and the wonderful Alaskan Guest Editor, photographer Ben Huff. Today we celebrate Ben’s work and his monograph, The Last Road, published by Kehrer Verlag. Through this project, Ben discovered the complexity of the Alaskan landscape – the physical and psychological line between wilderness and oil. For five years he traveled the road from his home in Fairbanks, and created a “melancholy portrait of a space that asks us to reconsider our perception of frontier”.

Ben is a photographer based in Juneau, Alaska. In 2014 he was an artist-in-residence at Light Work in Syracuse, New York. He has had solo exhibition of his work at the Museum of the North in Fairbanks, Alaska, the Pratt Museum in Homer, Alaska and the State Museum in Juneau. In 2015 he will have an exhibition in Portland at Newspace. His work has been published in Photo District News, Russian Esquire, The French Standard, and The New York Times among others.

Ben shares his perspective of being an Alaskan photographer:

The Great Land. The Last Frontier. North to the Future. All, euphemisms for the state of Alaska. We, inherently, are saddled with hyperbole here in the farthest north state in the country.

It’s interesting times here in Alaska. Crude is at less than $50 a barrel, and with 96% of our state revenue coming from oil profits, many are calling this the End Times. Again, we love our hyperbole.

End Times or not, the fiscal shortfall has our legislature gutting university and K12 programs of ‘unessential’ art classes. And, as there are no less than a dozen reality shows featuring the ‘truth’ of Alaska, it’s increasingly difficult to see this place called Alaska, and its future, clearly.

As with any place, there are as many ‘truths’ as there are storytellers. We have no shortage of serious photographers in Alaska, as well as many who have come from the outside and made wonderful and resonant pictures.

Photographers are drawn here because the hyperbole is warranted. Alaska is heartbreakingly beautiful, immense, wild and mysterious. We have some of the last untouched landscapes in America. Alaska is, in many ways, a great untapped artistic subject, and our history with photography is largely unwritten. The States Project has given us the opportunity to share pictures from hard working photographers in different corners of the state, who are contributing to this history.

My selection over the coming week is by no means a complete survey, but I’m excited to have the opportunity to share with the Lenscratch audience, five photographers who live in Alaska and are telling their story of what it means to be here, in this place, now. I count these five as friends and inspirations, with unique voices. Alaska is fortunate to have them.

The Last Road

Congratulations on the fantastic book! How did it come about?

Congratulations on the fantastic book! How did it come about?

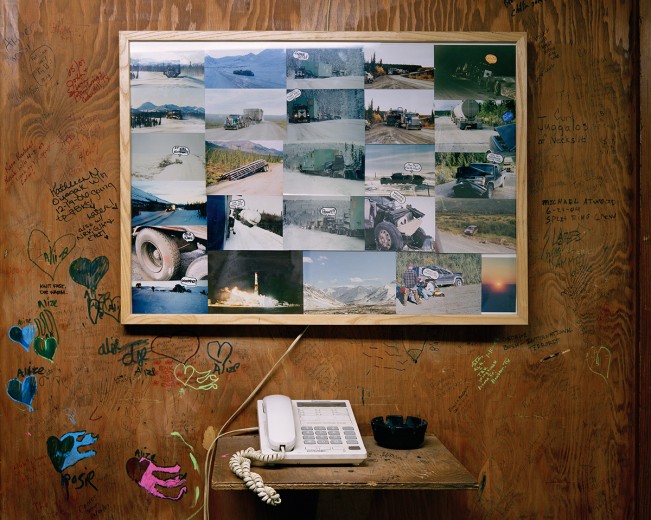

Thanks. The potential for the book was always part of my process of visualizing the work. Virtually my entire photographic education comes from the monographs of other photographers, and like most photographers no doubt, I had these dreams of the work resulting in a monograph. As I got deeper into the project, the object came more into focus for me. As part of my process between trips up the road I’d make these small, staple bound, short stories of sorts – just working out little sequences, or seeing how different seasons worked together or colors. I was drawn to that physicality.

Eventually, after I made my final trip, I experimented with a fully constructed maquette. The maquette was, ultimately how I worked out the edit. It was only in making the final object that I could make the hard decisions – to cut it down and be really deliberate in my intentions. I made a small edition of the final edit – hardcover and printed, glued and sewn at my small studio here in Juneau. It was such an illuminating process that was at the same time tedious and revelatory.

I really wanted to be able to show prospective publishers a clear vision of what I had in mind. The stars sort of aligned when I went to Photolucida in early 2013 and met Alexa Becker. I was familiar, of course, with many Kehrer titles and was anxious to show her my maquette. In short she just got it from the beginning – she could see it as a Kehrer title, and I trusted her immediately. I was very fortunate, as I’ve been through every stage of making this work. Can you describe how you came up with the project idea?

Can you describe how you came up with the project idea?

My wife and I moved to Fairbanks, site unseen, from Colorado in the summer of 2005. It came to the place with the mythic ideals of a Midwestern kid who remembers scenes of polar bears, Aurora and vast open frontier depicted in National Geographic magazine. Neither my wife or I were quite prepared for Alaska – it was an opportunity for her to go to graduate school in a perfect program for her, it all happened very quickly, and the move was something that seemed so ridiculous at the time, that we had to do it.

I really struggled with the space initially, the wild landscape that still existed, and the reality of Fairbanks and the infrastructure that accommodated us. It seemed that everything I had seen from outside Alaska was very one sided. I felt like a tourist, and that to some degree I had been duped. Naive to the core.

But, the love for this place was almost instant for both my wife and I. All of the complexity made it a richer experience. It’s not a perfect place. In many ways, that was a relief. Alaska became a place to make a life.

So, in 2006 made a day’s drive to the Arctic Circle, up the haul road, just because we could. That trip was a major turning point for me. I saw that day, very clearly, that the road had the capacity to illustrate my feelings about the place. It was a stage. A wild, complex, romantic, and new stage. Five hundred miles of dirt road that served as the physical and psychological line between oil and wilderness in Alaska. Boom and bust. Adventure and heartbreak. And a small cast of road weary characters. Your imagery reveals a beauty and brutality that is not for the faint of heart. Tell us about the people you have photographed in Alaska, as your portraits are an important counterweight to the landscapes.

Your imagery reveals a beauty and brutality that is not for the faint of heart. Tell us about the people you have photographed in Alaska, as your portraits are an important counterweight to the landscapes.

Traveling the haul road is a commitment, both logistically and financially. You don’t just stumble onto the road, or pass by on your way someplace else. There’s one entrance, at the south, and for almost five hundred miles it’s either North or South. Advancing or retreating. When you reach the end – the oil fields – the only option is to fill the tank with $5/gallon gas and head back South.

I was drawn to the people on the road that carried some of that weight of bearing witness. There’s an accumulation of miles there, a weariness of time spent behind the wheel, but also a greater emotional exhaustion that I was interested in. I often felt that the landscape was met with optimism on trips north, but after witnessing the oil fields at the end of the road, the same landscape held regret in its shadows on the way south.

I often referred to the people I met as ‘seekers’, and Karen Irvine touches on this in her essay in the book. I wanted to believe, projecting a bit of romanticism I confess, that those I met had experienced some great reckoning with the landscape and themselves.

There is the sense of being solitary in this project, which speaks to the truckers that traverse the state (who you have so wonderfully captured), but it also reflects you as the photographer. The work makes me consider the conditions in which the work was made–alone in your consideration of the landscape, in all kinds of weather with only your inner narration to propel you into action. Am I off the mark here? I can’t help but think it makes you consider your mortality.

There is the sense of being solitary in this project, which speaks to the truckers that traverse the state (who you have so wonderfully captured), but it also reflects you as the photographer. The work makes me consider the conditions in which the work was made–alone in your consideration of the landscape, in all kinds of weather with only your inner narration to propel you into action. Am I off the mark here? I can’t help but think it makes you consider your mortality.

Absolutely. The solitary nature of the work was important, for me as a photographer, for the project, and as a man and husband. My wife was ill during much of this work. She had a kidney transplant when she was in college, her mother’s kidney, and shortly after we moved to Alaska that kidney failed. We made many trips back and forth to the Mayo Clinic in Minnesota, and Anchorage, and she was on dialysis for three years before she was able to have another transplant. My mortality, her mortality, our new home and whether we could stay, our financial situation, our marriage, everything – it was all teetering on uncertainty. All of this informed the work. Leaving home and driving north where there were none of the comforts of home, no cell service, no radio – that escape was laden with guilt. But, in retrospect it also emboldened me. There was an urgency and commitment that was inherent in the unknown. There was a period of three years, where we didn’t know if we would have to pack it all in and move South. I wanted to make something out of my time here. And my wife believed in what I was doing and shared a love of the space and the story.

It became obvious, eventually, that many of these portraits were self-portraits in a way. And, I must point out that there aren’t any actual pictures of truckers. I recognize them, even honor them, in the book, but I was more interested in the folks who were there by choice. The trucks are evident, but the distance there is intentional. I was interested the individuals who had chosen a hard road, and for miles and miles had also been alone with their own thoughts and an impossible landscape outside their windshield.  You have produced images that show us a terrain where man feels insignificant and diminished in the shadow of the landscape–only a particular kind of person survives in that environment. Have you found a commonality with the population that is drawn to the north?

You have produced images that show us a terrain where man feels insignificant and diminished in the shadow of the landscape–only a particular kind of person survives in that environment. Have you found a commonality with the population that is drawn to the north?

My answer to this question is evolving. I’ve been thinking a lot lately about personal history, and what accumulation of events make a place home. When does that happen? I posed similar questions to the other photographers who we’ll me this week in an event to share their stories, but if I’m being honest to also help me gain some clarity.

July 8th will mark ten years for my wife and me in Alaska. It’s the longest I’ve lived anywhere, excluding my childhood home in Iowa. It doesn’t feel like ten years. Four years ago we moved from Fairbanks to Juneau, and in many ways it felt like starting over – an entirely new and confusing Alaska.

I have a difficult time calling myself an ‘Alaskan’. I’m not entirely sure what that means, or when the moniker is earned. Or, if it’s to be earned or only a birthright.

What I do know is that I’ve met, and am honored to call friends, some of the most diligent, honest, intelligent, and grounded people I’ve ever met here. It’s a truly unique place, which holds a hundred lifetimes of work to be made, and I intend to make one.

I’ve come to realize lately, that my outsider viewpoint is inevitable. And, in a way, I embrace it. I don’t hold nostalgia for this place. I have no memories of these landscapes of my childhood, or remember a time before the pipeline, or the Exxon Valdez spill, or Palin. My innocence has roots far away from here.

We’ll see later this week, with the photographers that we’ve assembled to represent Alaska, a diverse personal history and entry point to the discussion. Each relates to the space in different ways for different reasons. Each photographer, from a different vantage point, is dealing with Alaska today – what it means to be here, now.

What challenges did this project create?

As the story goes for every artist, I’m afraid, the financial obstacles are always the greatest. Always will be. The other challenges were just the price of making art, and necessary to the process. What camera did you use to create this work?

What camera did you use to create this work?

All of the pictures were made with a Toyo 4×5 view camera and a single lens. I actually bought the camera specifically for this project. I made my first pictures on the road with 35mm digital camera, but after the first trip had decided that I really wanted the experience of the larger camera. I was all wrapped up in the romanticism of it all. My good friend Dennis, who we’ll meet later in the week, had been working with an 8×10 for twenty years, and I convinced him to let me borrow his backup camera. Shortly after, I won a small grant from the Rasmuson Foundation here in Alaska which gave me the money to buy a used 4×5, a few boxes of film and the validation that I needed at that time to take the risk. Are you working on a new Alaska related project?

Are you working on a new Alaska related project?

I am, but it’s been a long time coming. I experienced a bit of a slump after first moving to Juneau. I was wrapping up The Last Road North, Juneau was an entirely new landscape to me, an island, I felt again like a stranger, again a tourist, and I was missing the network of other photographers in Fairbanks. I took too many bad pictures for too long here, and it did my head in. It took me a while after The Last Road North to feel comfortable in my process and to trust myself and my intuitions. But, that dark period artistically, in the end was useful. There will be others no doubt, and I feel better equipped to just get on with it.

But, it made me a better photographer, and I’m confident in the way things are unfolding now on the other side. I’ve been working on a project here in Juneau which loosely reflects the history of gold that built this town and the contemporary realities of this being the state capital. It’s good work, I think, and it’s taking shape.

And finally, describe your perfect day.

I’ve just bought a plane ticket for July to an island far out in the Aleutian chain that I’ve been dreaming about since we first moved here in 2005. The anxiety of this first trip, and the pictures that will be the result, feels like the first time I drove the length of the haul road. Being in that space – anxious, alone, standing in wonder before an immense foreign landscape with a new open-ended story to unfold – that’s a perfect day

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

Naohiro Maeda: Where the Wild Things AreDecember 26th, 2023

-

Adam Ottavi: The States Project: AlaskaMay 2nd, 2015

-

Ryota Kajita: The States Project: AlaskaMay 1st, 2015

-

Chris Miller: The States Project: AlaskaApril 30th, 2015

-

Brian Adams: The States Project: AlaskaApril 29th, 2015