Focus on South Africa: Jansen van Staden

In this second iteration of “Focus on South Africa” I wanted to include features on photography platforms, collectives, and teaching organizations in addition to artist profiles. In South Africa many photographers do not begin or advance their careers in secondary institutions, but rather through organized workshops, short courses, and extended mentorships. And while many Americans may be familiar with groups such as the Johannesburg-based Market Photo Workshop, a number of others have been established in recent years that are impacting the photography landscape in South Africa. These groups–and the networks of educators and mentors that work with them–are representative of a long-standing pattern of investing in and committing time to future generations of image makers that extends back to the Struggle era of the 1980s and 1990s and an “each one, teach one” practice among photography professionals. By learning more about the work of these groups we gain insight into the interests and concerns animating early-career photographers in South Africa, many of whom come from disadvantaged backgrounds that are traditionally underrepresented in the field, and who could not pursue the medium absent the support of the groups such as those profiled here. Two of the artists featured this week — Tshepiso Mazibuko and Jansen van Staden — have developed their work with support of Of Soul and Joy and Photo:, respectively. – Meghan Kirkwood

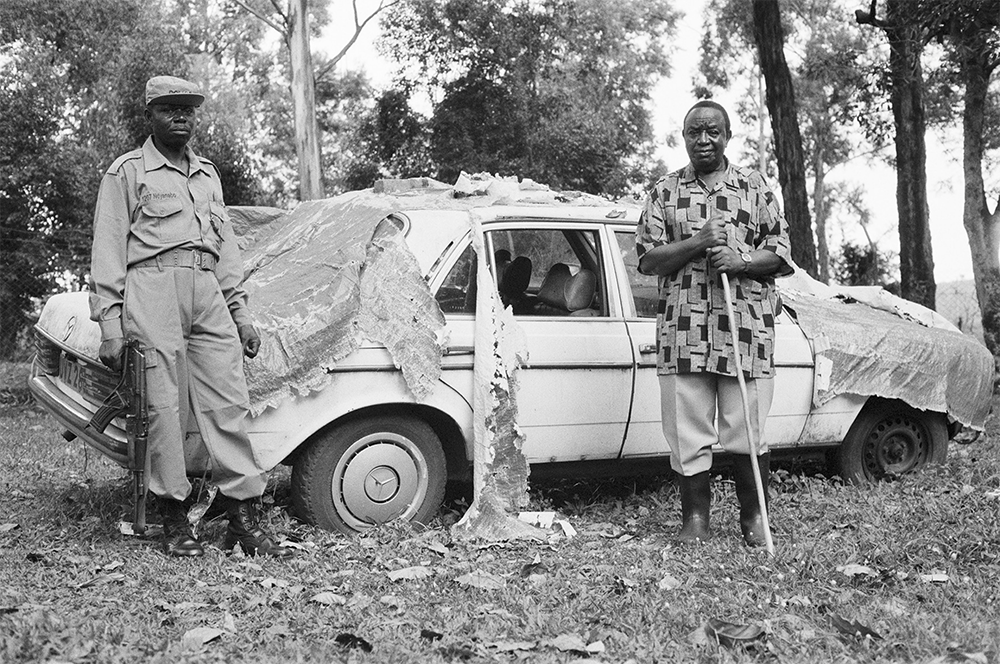

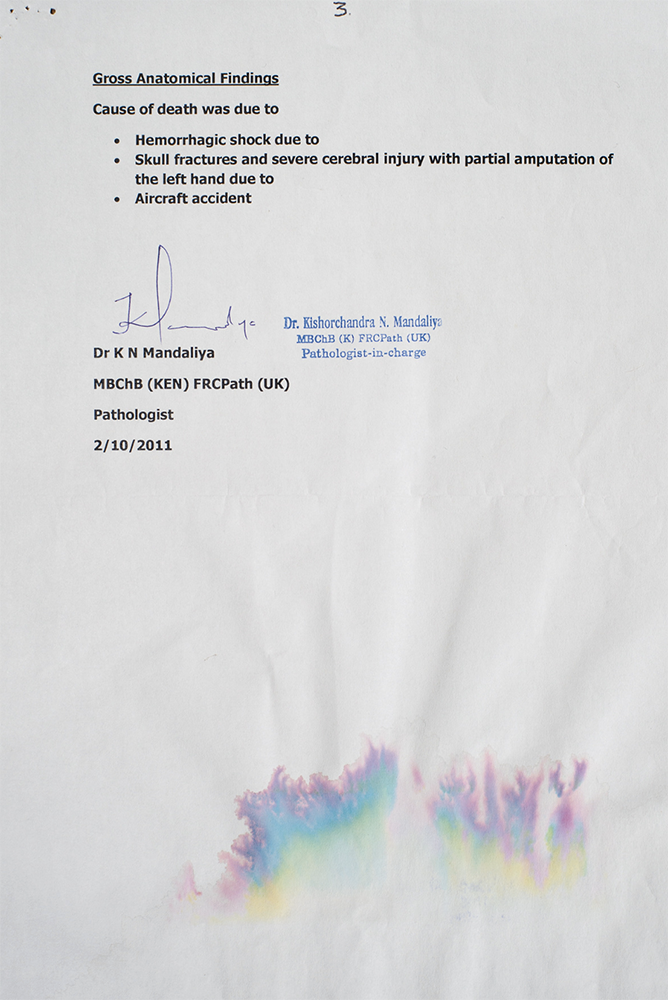

Jansen van Staden’s Microlight project began after the death of his father during a fatal aircraft accident in 2011. The crash occurred in Kenya and when an invitation to a masterclass in Nairobi came up years later, van Staden and his brother decided to visit the scene for themselves. The two spoke with the pilot, viewed the crash site, and had the chance to seek closure through pursuit of new information. van Staden photographed the process and shared the images with the class. His other project was pushed aside. “There’s something to this work,” they said. “You should keep digging, go deeper,” said Akinbode Akinbiyi.

Van Staden’s father loved to photograph–aerials, landscapes, clouds, deserts. He thought his father’s photographs may have a place in the series, and went looking in his father’s hard drive for images he could use. Searching the computer he found a letter his father wrote to his psychotherapist about his experience in the South African Border War. “My Decisions,” it was entitled; reading it van Staden learned new and horrific details about his father’s actions during the conflict. “This was not the man I knew,” he reflects; yet, reading the letter in which his father opens up about his conscription gave van Staden insight into the man he did know—a man who’s life was profoundly shaped by a set of actions and experiences that were only briefly mentioned, but never discussed, or worked through. “Slowly but surely, I put the pieces together about how my life turned out and what influence my father’s time in the army had on it.”

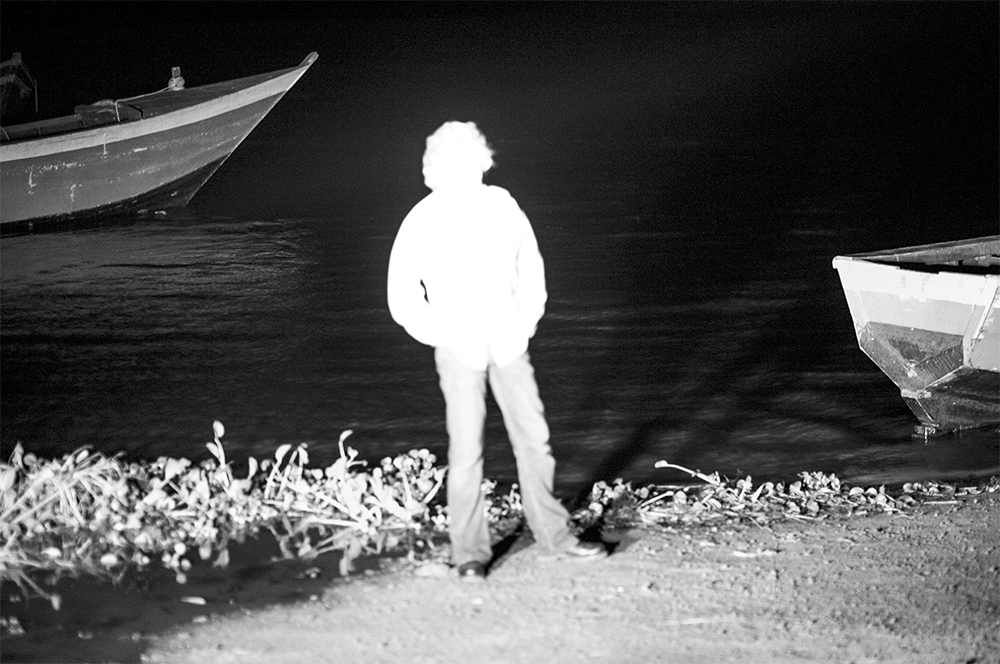

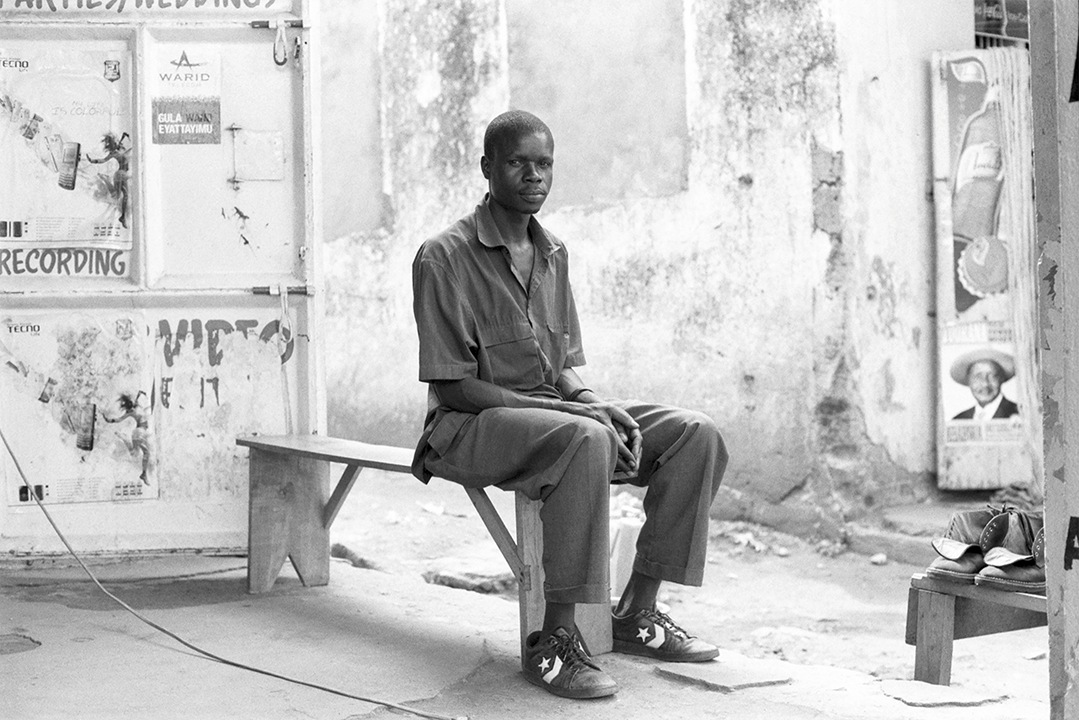

Microlight is a book project that interweaves van Staden’s own images, family photographs, and archival views from the war together into an non-linear stream of photographic stories. The project, van Staden says, is his way of dealing with “the death of my father metaphorically and physically,” and “coming to terms with the fact that my father wasn’t this hero that I as a child obeyed like a God.” Three threads extend throughout the book: the trip to Kenya, his dive into family archives, and his efforts to find alignment between streams of new information, by visiting his father’s relatives, and his own lived experience. Contextual information for the photographs is limited; Microlight has no introductory text, no page numbers, and van Staden buries extended captions in the back of the book. He sequences images with obvious signifiers later in the series. “I wanted to throw the reader in the deep end,” he says, “I wanted it to be an overwhelming, almost claustrophobic experience. When someone pages through the book, there’s no space within to breathe, no white borders, and they have to figure out what is going on.”

A format that allows for open engagement with the subject matter is paramount for van Staden; even as he inundates his viewer with emotive imagery, he withholds or delays giving information that could help organize their feelings into an opinion or position. This format also speaks to the sensitive nature of the book’s subject, and the care with which van Staden is concerned to speak about it. The twenty-three year long South African Border War had and continues to profoundly affect South Africans culturally and politically. The war was primarily fought in neighboring states, and aspects of the war were kept secret from the South African public and combatants themselves. “The result,” says Christo Doherty, “is that the conscripts — the great majority of whom went into the army directly after school — were left with the ethical legacy of their military service in a secret or invisible war.” van Staden feels strongly that the impacts of the Border war should be recognized, even as he acknowledges substantial differences of those impacts among affected populations. Unresolved trauma manifests itself across generations, he argues, and limiting discussion prevents conscripts from doing the work of reflecting on their actions and examining their own ideologies. “If you go to a war thinking that you’re doing the right thing, and you’ve been raised in a certain ideology and you believe it, you never questioned it, and all of a sudden you come back from the war with this trauma, then it takes a while for you to start questioning that ideology. And up until that point, you and your family are suffering from this,” he says. “Somewhere it has to stop and it only stops with awareness, and questioning. Questioning, and looking at yourself. ”

Other photographers such as Jo Ractliffe in As Terras do Fim do Mundo and the Borderlands; and John Lienenberg’s Bush of Ghosts explore themes and spaces of the Border War, but differ from the personal journey and vulnerability put forward in van Staden’s Microlight. Many of the photographs echo the reflective process with which he pursues a kind of resolve. A photograph of himself sitting cross-legged, mimicking his father’s posture, he says, represents acceptance of the history passed on to him. “I’m not proud, but I’m not refusing the history that I have. I’m taking it on and accepting that this is my history. This is where I’m from and this is what I’m dealing with.” he says. But even as van Staden layers images with personal content the book also carries social messages, even if van Staden is prepared for his audience not to receive them. In this sense, the work recalls a particularly South African impulse to create work that is socially relevant, even as artists avoid didacticism or instrumentalist imagery.

The book winds backwards from the whirlwind of the opening sequence and ends with what feels like some of the most personal images in the series. The last two images–a straight-on view of a fuselage and a damaged camera–bring together some of the most potent themes in the book, and, seemingly, the most intimate. Looking at the plane, covered and stored, it’s hard not to think of the before–the plane in flight, active, moving—when viewing the present; a process not unlike viewing archival imagery. The damaged camera belonged to van Staden’s father. It survived the fatal crash. After discovering a defect in his own camera of the same model, van Staden paid a technician to extract the sensor and shutter from his father’s machine and put it into his. The photograph, wherein van Staden stares back at the camera with an almost clinical gaze, speaks to the objective remove with which he tries to look at his father’s life, even as the image is made with something that bears his father’s indelible mark. Closing the book reveals a small line drawing of a house and car, a doodle from his father’s army notebook, something that van Staden uses to represent the normal life his father never had. Something very simple he always desired. The journey to these final three images from the opening sequence feels a little like falling, but not being sure what ground you’ve landed on. A viewing experience, in other words, that is not unlike van Staden’s own process.

Jansen van Staden: b.1986 South Africa. Van Staden is a South African photographer and author of Microlight. He uses street photography as a conceptual entry point to reflect on personal and social constructs of belonging and disconnect. He became a fellow at the Goethe Institut’s Photographers’ Masterclass in 2017 and graduated in 2018. His work was shown in Cities and Memory at Brandts, Odense as part of the Photo Biennale in Denmark (2016) and in Nimes, France as part of the South African show “Resiste” at NegPos gallery (2017). He recently received the CAP prize (2019) for his series Microlight, and the concurrent exhibitions and screenings have started traveling Europe and Africa. Van Staden was a nominee for the 2020 Paul Huf Award. The photobook, Microlight, was exhibited at the 2020 Photobook Week Aarhus festival as part of the exhibition Intimacy and Resistance, curated by John Fleetwood. Van Staden lives and works in Cape Town.

1. Doherty, Christo. “Trauma and the Conscript Memoirs of the South African’Border War’.” English in Africa 42.. 2 (2015): 25.

Meghan L. E. Kirkwood is a photographer who researches the ways landscape imagery can inform and advance public conversations around land use, infrastructure, and values towards the natural environment.

Kirkwood earned a B.F.A. from Rhode Island School of Design in Photography before completing her M.F.A. in Studio Art at Tulane University and PhD at the University of Florida. She currently works as an Assistant Professor of Visual Arts at the Sam Fox School of Visual Arts and Design at Washington University in St. Louis, where she serves as area head in Photography.

Kirkwood’s work has been exhibited internationally in solo and group shows at venues including Blue Sky Gallery (Portland, OR), Filter Space (Chicago, IL), Bangkok Art and Culture Center (Thailand), ArtSpace Durban (South Africa), Colorado Photographic Arts Center (Denver, CO), Rosza Art Gallery (Houghton, MI), Plains Art Museum (Fargo, ND), PH21 Gallery (Budapest), Midwest Center for Photography (Wichita, KS), Yost Art Gallery (Highland, KS), and Montgomery College (Tacoma Park, MD).

Her photographs are held in several private and public collections, including the RISD Museum of Art, the Museum of Contemporary Photography in Chicago, University of Idaho, Minot State University, North Dakota Museum of Art, and the University of Florida Genetics Institute. Her work has been featured in publications such as Lenscratch, Don’t Take Pictures, Oxford American, New Landscape Photography, Landscape Stories, Don’t Smile, and Ours.

She has received numerous awards and fellowships to support her research, including from the Crusade for Art Foundation, selection as a Center Santa Fe Top 100 Photographer, full fellowships for graduate research at University of Kansas, Tulane University, and University of Florida. She has also received full funding to participate in artist residencies through the National Parks Service, the Vermont Studio Center, and the Lakeside Lab.

In tandem with her studio practice, Kirkwood also researches in the fields of African art and the history of photography. She holds an MA in Art History from the University of Kansas, where she researched African monuments designed and built by North Koreans, a study that was published in A Companion to Modern African Art (eds. G. Salami and M. Visonà). Her dissertation examined the uses of landscape imagery by contemporary South African photographers. Her writing on photography has been published in Lenscratch, Social Dynamics, Exposure, and Photography and Culture.

Kirkwood is a native New Englander, but lives together with her family in St. Louis, Missouri. When not photographing or traveling, Kirkwood trains for and competes in marathons.

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

Earth Week: Aaron Huey: Wallpaper for the End of the WorldApril 26th, 2024

-

Earth Week: Casey Lance Brown: KudzillaApril 25th, 2024

-

Tara Sellios: Ask Now the BeastsApril 6th, 2024

-

ALEXIS MARTINO: The Collapsing Panorama April 4th, 2024

-

Emilio Rojas: On Gloria Anzaldúa’s Borderlands: The New MestizaMarch 30th, 2024