The Dynamics of Photography and Disability: Aurora Berger

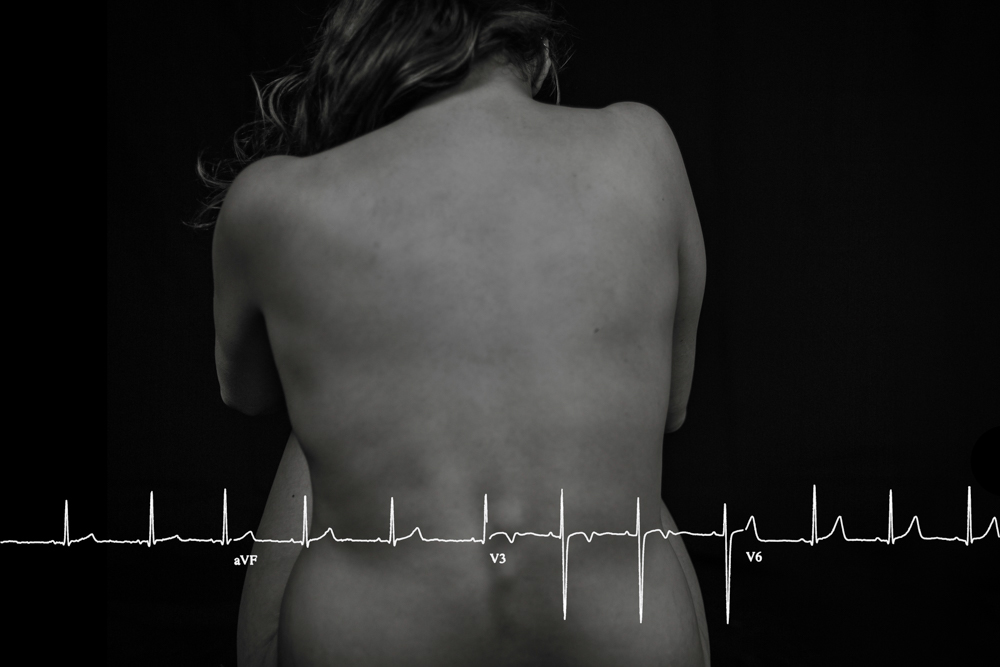

© Aurora Berger, Ekg, Aurora sits with her back to the camera against a black background. Her scoliosis is apparent and you can see her vertebrae at the bottom of her back. The image is cropped just above her shoulders. A white EKG line is etched across her lower back.

This week we are looking at projects by disabled/chronically ill photographers. The definition of dynamics is forces or properties which stimulate growth, development, or change within a system or process.” Each of these artists is approaching their work in ways that embrace this meaning, enacting change and raising important questions about societal systems through their ideas, craft, and processes they use.

Aurora Berger is a queer disabled artist working with photographic and alternative processes. Coming from an academic background, and currently working in education, Berger uses language and imagery to challenge ableist and heteronormative ideas. She creates works that investigate the concepts of normalcy, disability, agency, visual acuity, and interpretation. Berger holds an MFA from Claremont Graduate University, as well as a BFA and BA in Art Education from Prescott College. She is the recipient of the Kennedy Center VSA and Wynn Newhouse awards, and is a current resident of the Art and Disability program through Art Beyond Sight and the 2021 Slant Projects artist programme. Berger has presented her work at several conferences including the 2020 College Art Association National Conference and her writing has been published by the National Institute for Learning Outcomes Assessment, Drkrm Editions, and in a recent anthology from Brill | Sense.

Working within the frameworks of capacity and disability, I use photographs to examine my own identity. As a physically and visually disabled artist, my work is a reflection of how I see the world.

Although my works are largely photographic, the medium that I have often used to realize them is cyanotype, an alternative photographic process that uses UV rays to print. These cyanotypes are an extension of my self portrait work, testing the materiality and temporality of the images, allowing me to embrace chance and change in the medium and my body.

My work is about reckoning with a medical system that values numbers over wellbeing, body parts over the whole. My work is about existing in the body that I have, in the life that I am living. It is about inhabiting spaces, perceiving surroundings, and above all, the process of survival. -Aurora Berger

MB: Welcome Aurora. Would you please tell us a little bit about yourself?

AB: I’m a queer disabled artist from Vermont. I got my BFA in studio art/visual arts and a BA in art education from Prescott College. I got my MFA in visual arts from Claremont, Graduate University. I currently work in elementary art education and also in special ed, I’m also a paraprofessional. I’m an academic and just recently had a chapter, Disability Arts Manifesto, published in a book called Redefining Disability from Brill. And I don’t know that there’s that much else to say about me.

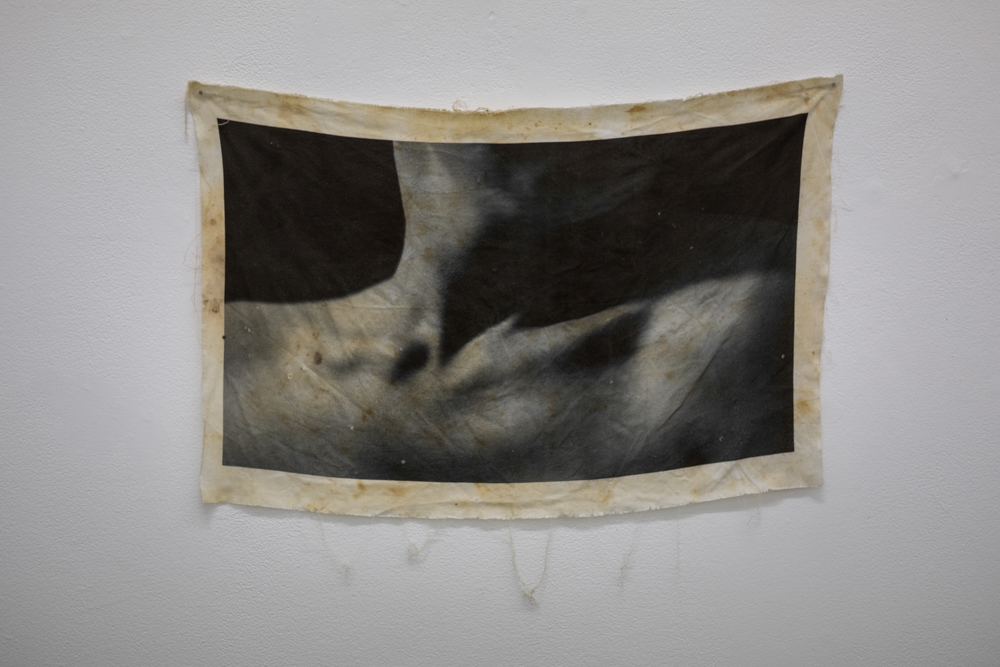

© Aurora Berger, Bleeding Out, A black and white nude photograph of Aurora (a white woman) printed on fabric, hangs in a forest. Aurora sits on the ground against a white background with her back to the camera and her arms are wrapped around her torso. The photograph has been nailed to two maple trees, and sap from the trees has stained the fabric.

MB: What does disability mean to you personally? And what does it mean in your work?

AB: I have a lot of thoughts about disability and access: disability and access to work, disability, and access to transportation. What it is to be disabled in a rural environment. I think disability is an all-encompassing thing, and that you can’t separate it from other aspects of existing because it really affects everything. In a way that you start to forget. I constantly forget how much disability impacts things that I’m doing until somebody else says, ‘Oh, that’s annoying that you have to do that’ [in regards to accessing an accommodation] And I realize ‘Oh, yeah, You’re right. That is annoying.’

I also think that there are a lot of social barriers for people with disabilities. But I do think that for me primarily it’s been medical barriers rather than social barriers because it’s been a medical system that’s not working. I tend to get frustrated with the whole social model thing because that doesn’t apply to my situation. People like to pretend the medical model isn’t happening and I don’t think the medical model works either, but people tend to be like ‘Well, the social model if we just made allowances socially for everybody it would be fine.’ I’m like ‘Well that really wouldn’t fix chronic pain.’ You think that (the social model) gets rid of all of the problems. But you forgot about the actual existing part.

I think that the medical system is really dehumanizing for disabled people, it’s really hard to be assertive and get your needs met. No matter how much you go into an appointment, with a list of things that you need to have done and questions you have, you can still leave that appointment with absolutely none of it. It’s so hard to be assertive in a medical environment where you’re being looked down on and doctors are really judgmental of patients that they perceive as having googled things. And so, if you come in, and you show that you have any medical knowledge, they will immediately shut down all of your ideas, all of your questions and they’ll just dismiss you. And I think that aspect of the medical system is holding back a lot of chronically ill people, especially during your pandemic where it has been really difficult to get medical care, to begin with. So then, when you wait 5 months for an appointment and they shut you down, and then you have to wait another 5 months to get that question answered- it’s not doing anything for the patient, that’s not helping anybody. It’s all intertwined, which is why I just don’t think any of the models really work.

Read more about the Medical and Social models of disability HERE.

MB: Yeah, have you read about the complex model?

AB: Yeah and that’s sort of my favorite one. There’s a Tobin Siebers essay in the giant Disability Studies Reader, that’s really really good about it. It’s called Disability in the Theory of Complex Embodiment.

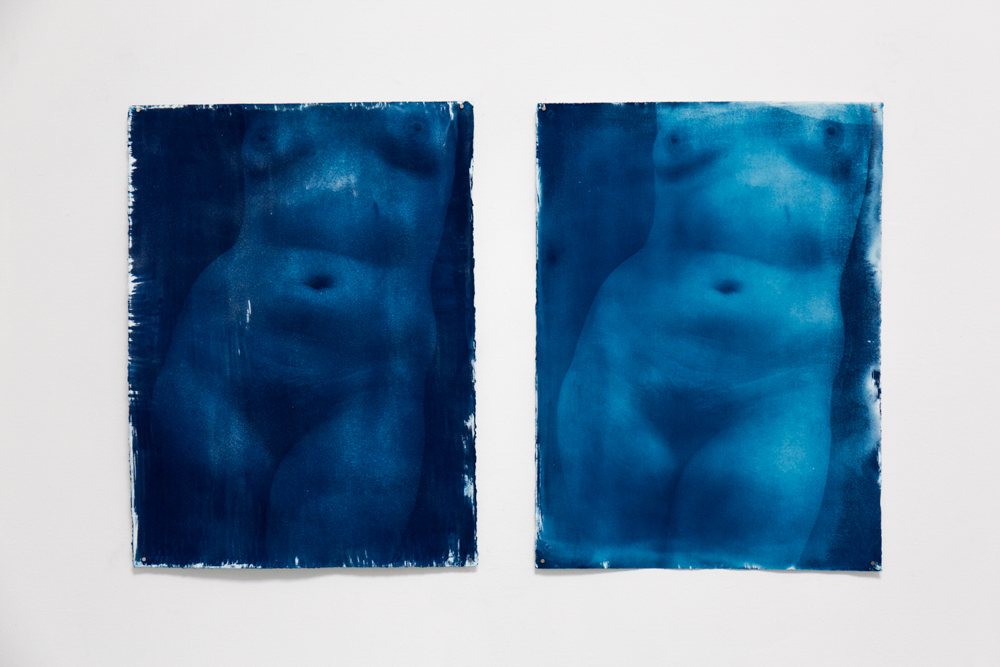

© Aurora Berger, Venus (duo), Two blue prints of the same image: A woman’s nude figure shown from mid thigh to above the breasts. The print on the left is darker than the image on the right. Her arms are not visible referencing Venus de Milo.

MB: What does disability mean in your own work in your artwork?

AB: My deal is that disability functions in art as both an aesthetic and also a framework. There’s a framework of disability within art and there’s also an aesthetic of disability within art. Those are different things and they function differently but they’re equally important.

A lot of my art is built within a disability aesthetic where that’s sort of the idea that I’m thinking about as I pull together images. I have pictures that look like the Venus de Milo, or things like that, where I’m directly referencing something that we’ve determined is a disability icon or right image. Or I tore the artwork, and so that tear is part of the aesthetic of disability, according to Tobin Siebers and also me.

But then there’s also the framework of disability within art so I feel like when I create cyanotypes I’m sort of working with disability as a framework more than as an aesthetic because the aesthetic of disability… I mean a cyanotype is just a blue photograph in that aesthetic sense. I mean it’s a cool blue photograph, and maybe it’s got some funky brush marks on it, or it’s got something interesting going on with the way the images are layered, but aesthetically it’s a blue picture.

But when you think about it, within a framework of disability a cyanotype is made through happenstance and natural processes, there’s so much chance that goes into creating alternative process photography. There’s so much of just letting go of control and I think to me that feels like a framework of disability rather than an aesthetic of disability, and letting those images be imperfect and embracing that imperfection in them is sort of a disability aesthetics. I think the process of creating them is what really drew me to cyanotypes.

I have a manifesto that I wrote about Crip Art, and I wrote a set of guidelines for disability aesthetics. I’ll read you this little section of it:

We all have our own versions of what disability looks like. These images come from popular media and people we know. Disability looks like Jillian Mercado at New York Fashion Week and Selma Blair at the Oscars. It’s One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest and the Fault in Our Stars. For me, disability looks like long blurry walks in the woods. It looks like Lucio Fontana’s slashes and Tracey Emin’s bed. It looks like Bob Flannigan hanging from the ceiling above a hospital bed and Viktoria Modesta’s glowing prosthetic leg. It looks like the Venus de Milo and her forgotten arms, it looks like hospital visits and disheveled beds and abstract Crip joy. It looks like friendship. Scars. Soft curves. Hard edges. It looks like my bed.

My point is, no aesthetic ideal is singular. My visual understanding of disability will always be unique to my experience. I am a disabled artist so I see disability in art even when it was not intended. Wandering through an art book fair with another disabled friend, we find disability aesthetics in places they were never meant to be: a book on the design history of chairs called Be Seated, a book about cognition titled Blind Faith. This essay is not intended to be a directive; this is not the definitive way of understanding Disability Aesthetics, but rather a personal manifesto of how I view art, disability, and the world around me. To that end, I have developed a list of guidelines for disability art and aesthetics.

Guidelines for Disability Aesthetics

Work does not need to be visual

Work does not need to be aesthetic

Work does not need to be made by a disabled artist but must be informed by or in reference to the lived experience of being disabled (not a secondhand experience, i.e. a caregiver or family member to a disabled person)

Not all art by disabled artists is disability art

Not all art that relates to disability is disability art

Disability art is underpinned by the experiences of being disabled

I struggle with this word, aesthetic, because I don’t know how to make it fit the Disability Art that I know and love. Disability is intrinsically beautiful, but beauty is not a tenet of disability art. Disability Art transgresses beauty; it is bigger, more complicated than that. Disability Art grows from a lineage of ugly laws, physiognomy, the very basis of the medical system, remnants reminding us that beauty is not a sociological framework for disability.

…

Disability art, crip artistry, disability aesthetics… these ideas haunt me. They hover around me like ghosts, begging for their problems to be resolved. But the deeper I fall down the black hole of theory, of questioning, the more entangled I become. The reality that I am just beginning to accept is that perhaps I have no solutions, that perhaps there are none to be found. This is the gift and the curse of a constantly evolving culture and language, that there is no right answer. For now, this is the best that I can do and perhaps, for this disabled body-mind, that can finally be enough.

But also we know it won’t be because I’m a fucking mess. It’ll never be enough.

MB: I really love the way this chapter came out.

© Aurora Berger, Holter, A black and white photograph of my chest with wires and electrodes attached. My arms are blocking my nipples and most of my breasts from the image.

© Aurora Berger, Marks, A close up black and white photograph of Aurora’s arms with bruises on the insides of her elbows from IV’s and blood draws. Water drips off of her left arms.

MB: I remember recently you said something that really resonated with me – It was about the experience of the disabled body being parceled up in the medical environment, especially when you live with multiple disabilities. Can you share more about that?

This is something that I think about a lot. The medical process is one of surrendering control. It breaks you down into a summation of parts, fragmenting your body and your identity. This is really hard for us as disabled individuals because we are more than a list of symptoms or file of medical data. At the same time that data and those symptoms dictate the way that we live our lives and it can be really frustrating to only be seen as a single symptom or body part because the rest of my body, the rest of myself, are outside of their purview. To a doctor, I am often no longer a living, thriving body-mind but a singular organ with a mathematical degree of efficacy.

MB: I know you research photo history and disability representation. Can you share more about what you’re researching and writing about at the moment? And how does this research influence your work?

Oh, my God, I could talk about that for like 8 hours! I am working on a book that I have been working on for a long time. It’s a disability and contemporary art book. It’s sort of in the same category as Ann Millet-Gallant. There are very few books about disability art out there. I really wanted to explore more ideas that had to do with Disability Art and also just look at contemporary look at art of the last 100 years. Because there’s so much happening, and there’s just nothing written in an academic published form I really needed to set the record straight on Joel Peter Witkin and I needed to set the record straight on Diane Arbus. Those are 2 of the 4 chapters in the book. Then I have a bunch of different little chapters broken down like the sort of topics that really I felt needed to be further explored.

I wrote one on outsider or art, I wrote one on institutionalization and photojournalism, and I wrote one on disability as embodiment. So sort of looking at like cyborgs and amputation, and like physical difference, in the way that physical embodiment has been a piece of contemporary art. The chapter that I started working on at the end of last summer is a chapter about death as a medium, death as a lens for looking at art, and the way that we have taken non-disabled artists, and use their deaths to put them within the canon of disability art. So people like Diane Arbus or Francesca Woodman or Robert Mapplethorpe, who are all sort of people who come up when you’re looking through disability art stuff that weren’t necessarily disabled, or they were, but they certainly weren’t making disability art. But their art is now considered to be within the cannon of disability art. So like Francesca Woodman, her art wasn’t supposed to be disability art. But now we look at it as art about depression. And the same with Robert Mapplethorpe, like we use his art as a lens to look at the AIDS crisis and say, like this is a documentation about a global medical crisis, looking at a very small segment of it. If you look at his Black Book, if you look at that book, like within a few years half of the men in that book were dead.

So I was doing a bunch of work on Ana Mendieta and Hannah Wilke right, and people like that, whose work has really become part of a disability art conversation. But it didn’t happen until after they had passed away and so they don’t have any say in the way that we interpret their work within disability, and also the way that we sort of think of death, or understand death and why we fear death and the way that like art changes anyway. This is my description for the chapter that I wrote in my proposal:

This chapter looks at the art of deceased artists, and the impacts that these deaths had on understanding of their art. Both before and after they died. In displaying artists deaths we will explore deaths by suicide. Diane Arbus, Francesca Woodman, Illness Bob Flanagan, Frida Kahlo, Robert Mapplethorpe, and external forces (Eva Hesse, Hannah Wilke and Ana Mendieta) the way that we understand the works of these artists have been irrevocably changed by their deaths, and I believe this is merely a coping mechanism for our fear of death. Our need to explain why things happen. We begin to alter stories to make death easier to understand. Diane Arbus photographed freaks because she was mentally ill and looking for community. Ava Hess’s work becomes a metaphor for disability even the work made before her brain tumor by interpreting an artist’s work through the lens of dying. I argue that we enter into the realm of disability studies as a framework for understanding.

© Aurora Berger, In the Ferns, A black and white photograph of Aurora, naked, curled into the bottom right corner of the frame. She is surrounded by ferns and fallen trees. Sunlight falls in patches across the picture illuminating areas of the foliage and areas of Aurora’s skin.

MB: How would you say that the research becomes part of your work? Does it?

AB: Yeah, it definitely does so. A lot of my self-portraiture is inspired by my research. A lot of the research informs the way that I mean really it’s inseparable. I guess because my photographic work is really all self-portraiture. And my research is constantly informing who I am as a person. and the way that I think about myself and disability and my lineage, and where my place is within that lineage of disability art. It’s constantly changing the way that I think about my own photographs. And so, as I’ve made more and more work, the way that my work fits into the things that I’ve learned through my research changes. I think that’s especially true for something like my research on… like all of the research that I’ve done on disability and photography whether it’s photojournalism or the work of Diane Arbus, or the work of Joel Peter Witkin. It changes the way that I think about my images and so it changes the way that I make my images. And it’s also really impacted the way that I think about how disability impacts my life. Because, as I look at the way that impacts other people’s lives of course like it changes the way I think about myself, to lead on from that thought.

© Aurora Berger, Clouded, A cyanotype macro photograph of Aurora’s left eye. The image is printed on a sheet of watercolor paper using a chemical process to create a monochrome blue image. The eye is extremely detailed with a stripe of white fibrosis across the center of the pupil.

MB: Can you share some about your process? Why do you choose the photographic materials you use?

AB: So cyanotypes, they’re pretty you can’t get away from that. There’s no doubt about it. I love that cyanotypes are a beautiful color of blue. And I love the way the grain of the paper comes through. You can’t get that with you know inkjet printing. I love the way that you are sort of collaborating with nature. when you create a cyanotype, you can’t control what the sun’s going to do, even if you’re in a cloudless sky but the time that min exposure is up. It could be completely stormy above you, and you have no control over that. And then, because a cloud passed over, you’ve got to just be like, ‘Well, if it’s a 9 min exposure, now.’ Especially if you’re treating your own cyanotype paper, you end up with all kinds of interesting brush marks and edges, that don’t match up and all kinds of interesting marks, and I can’t think of the word that I’m trying to think of, which is not the marks ephemera…I guess I’m gonna say it’s like your energy and your mark-making becomes a part of that image.

And especially because my eyesight is crap when I’m working in a dark room, (or my version of a dark room in Vermont, which is my bedroom with all the lights off which is why there is cyanotype solution all over my floor) I can’t see my paper, I have no idea if I’ve coated it correctly, and I will not know until it’s long dry and I’m not going to go back in and put a second coat on those spots. And so a lot of times I create this paper and then I’m like ‘Well, this is the paper we have so this is the paper I’m using.’ And then it becomes even more interesting because then I’m looking at the paper, like trying to look at it really fast, and then put it back in the box like, not overexpose it, and then looking at my negatives and trying to think what negatives will match up with this shape that I’ve created. Because I end up with like these blank spots of white where you know you’re not going to get an exposure, and sometimes that really adds to the image. I’m thinking of a photo – it’s of me laying on the ground like it’s just my face, and I’m like laying in some leaves, and it looks like I’m asleep which is why I called this Titania because I was feeling Shakespearean. But there’s a place where a brushstroke is missing, and it fit right into like where my head was and it just felt like that was the paper that was meant to go with that image like there was no question.

© Aurora Berger, Titania, A cyanotype of Aurora laying on her side on a sea of dried leaves in the evening light. Her face and shoulders are in the picture, her eyes are closed, and her left hand is cradling her face. The top of the image has white uneven brushstrokes from where the chemicals were brushed on. The edges are golden yellow like an old document.

Other materials are – I did a bunch of work on cotton because I was working with nature, and I was putting those prints out into nature, and it felt like putting something synthetic up in the woods would just be sacrilegious somehow. So I printed a bunch of work on cotton. I hung those in the woods for like 2 and a half months. That was a really cool project and something I’d like to do again sometime, maybe in a different environment, or with different materials somehow. Again, collaborating with nature, embracing the lack of control that you have. Once you let something go, and once you have let it go out into a new environment that you can’t control.

© Aurora Berger, Softly, A black and white photograph of Aurora’s hands and leg, printed on white fabric and hung between two yellow birch trees. Aurora’s hands and legs are on the right side of the frame. The left side of the image is empty and contains folds in the top left where it is attached to the tree. The folds of the fabric contain an ombre effect of yellow/orange sap bleeding into the print.

MB: This is actually like right along the same lines of my next question for you, which is that I love when you put your prints directly into the natural environment to be altered. What started this work? How did you feel like you knew a piece was done?

When I was in grad school living in California, I had to come back to Vermont for what turned out to be 2 and a half months. I wasn’t expecting it to be that long. I came back to have eye surgery. I was expecting to go back to California a lot sooner. But then my eye surgery failed. I had to have another surgery, so I had to stay longer. So the original plan was that they’d be out for like maybe a month, and they ended up out in the woods for 2 and a half months.

But the real reason was I had access to a large format printer, and I was like I’m gonna buy a giant roll of inkjet cotton and I’m gonna print as much of my work and as many of these portraits as I can and I’m gonna take them back to Vermont. I’m gonna do something with them because if I’m going to be in Vermont for the whole summer of my MFA I need to do something with that. I can’t just be like not doing my work, you know because when you’re doing a grad MFA Program you really get into this mindset of like if I’m not creating work, I’m a failure which is horrifying. I didn’t really know what I was going to do with them.

But I thought, ‘Oh, it’d be really interesting to hang them up in the woods’, and I think I can pull that off like, you know, logistically, you never know what’s going to work until you get there. I needed to do something big, but I also needed to like do something that was manageable for me and so I took all this cotton work home and hung it up all over the place around my house and a bunch of other people’s land. And then I just would go back, and check on them every week or two. I had them all over the place and I had sort of like a mental map of where they all were. When I was leaving to go back to L.A., I took down all of the ones that weren’t on our property. So we only own like a teeny piece of land, and I only had 2 that were on our land. but I took down everything. I left those 2, and then I wanted to see how those looked a year later. But my father took them down in that fall.

© Aurora Berger, Submerged, A black and white photograph of Aurora, printed on fabric, is submerged beneath the water of a forest stream. The photographs show Aurora standing against a dark background, cropped from mid-thigh to just above her breasts. She is thin with visible scars, stretch marks, and pubic hair. You cannot see her arms.

MB: Do you think you’ll ever try that again?

AB: I would like to. I don’t have access to a printer anymore. Health-wise it’s gotten a lot harder for me to trek into the woods. That’s a bit of an issue, but I’d be interested in trying it with some other formats. I don’t know about cyanotypes because I don’t think I want to let the cyanotype chemicals get into the groundwater. But they’re definitely other methods that are interesting, and I have a whole lot of the blue sunbeam cyanotype dye for fabrics. So at some point, I should figure that out.

© Aurora Berger, Cleft (3 months), A very distressed fabric print of a high-contrast black and white photograph of Aurora’s collarbone. The fabric print was left in the woods for 3 months. There is residue on the print from rain, tree sap, and other environmental factors. The residue appears as sepia toned areas along the print.

MB: What have you been working on recently?

AB: I’m going to have an Instagram post for the series disabled artists respond to the Metropolitan Museum of Art, #Met Access.

I have work from presenting at the Common Field 2021 Convening going up on their online archive. And my chapter Disability Arts Manifesto was published in a book called Redefining Disability from Brill.

MB: Who are some artists that have influenced you or inspire your art practice?

AB: Gosh, so many. Francesca Woodman and Robert Mapplethorpe really influenced the way that I photograph myself. Mari Katayama and Zanele Mulholi who are unapologetically themselves. Sally Mann and her gorgeous alt-process work. Laura Aguilar, Anne Brigman, artists who understood the way that the natural world grounds us. I love the work that Martin D. Koehler and Katie Lee made in Glen Canyon before it was dammed. Edward Weston. Bob Flannigan and Sherree Rose. Ana Mendieta. Disabled artists everywhere.

© Aurora Berger, Waves, A black and white photograph of Aurora sitting in the negative space created by the roots of a fallen tree. The tree’s roots arch around her, and she is curled into the space naked with her eyes closed. She has long blond hair and pale skin.

Megan Bent is a lens-based artist interested in the malleability of photography and the ways image-making can happen beyond using a traditional camera. This interest started to occur after the diagnosis of a progressive chronic illness. Drawn to image-making processes that reject perfection, accuracy, or any certainty in results, she is interested instead in processes that reflect and embrace her disabled experience; especially interdependence, impermanence, care, and slowness

Her artwork has been exhibited nationally at The Halide Project in Philadelphia, PA, The Center For Fine Art Photography in Fort Collins, CO; The East Hawaiian Cultural Center/HMOCA in Hilo, Hawai’i; Flux Factory in Long Island City, NY; El Museo Cultural, Santa Fe, NM; The Foster Gallery, in Dedham MA; Soho Photo Gallery in Tribeca, NY; the Austin Central Library Main Gallery in Austin, TX, and internationally at F1963 in Busan, South Korea; Alternative Space 298, Pohang, South Korea; and Fotosotrum in Barcelona, Spain.

She is currently an artist in residence at Art Beyond Sight’s Art + Disability Residency and has been an artist in residence at the Nobles School in Dedham, MA, and the Honolulu Museum of Art, HI. She has presented her work at Atlas Obscura: The Secret Arts, The Pacific Rim International Conference on Disability and Diversity in Honolulu, HI, at Other Bodies: (Self) Representation, Disability and the Media at the University of Westminster in London, U.K., and at Critical Junctures at Emory University in Atlanta, GA. Her work has been featured in Analog Forever Magazine, Fraction Magazine, Too Tired Project, Rfotofolio, and Float Photography Magazine.

Follow Megan Bent on Instagram: @m_e_g_g_i_e_b

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

Jonathan Silbert: InsightsFebruary 19th, 2026

-

Olga Fried: Intangible EncountersFebruary 18th, 2026

-

Anne McDonald: Self-PortraitsFebruary 17th, 2026

-

Review Santa Fe: Elizabeth Z. Pineda: Sin Nombre en Esta Tierra SagradaFebruary 6th, 2026

-

Carolina Baldomá: An Elemental PracticeJanuary 5th, 2026