PROOF: Caleb Cole: In Lieu of Flowers

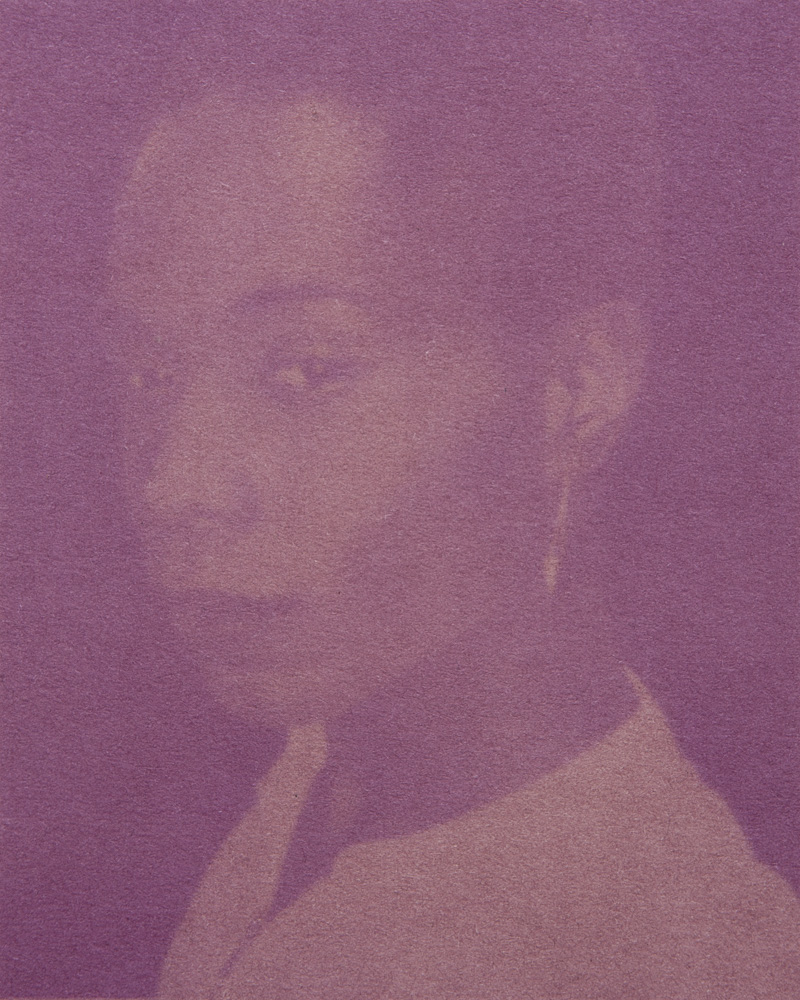

©Caleb Cole, Aja Raquell Rhone-Spears, 2020, from In Lieu of Flowers, All images 4 x 5 inches, Anthotypes from Rose Petals

As straightforward and challenging as it could be – one of art’s purposes, for that matter, Caleb Cole’s self-reflexivity, defies assumptions, generates questions, and constantly challenges apparently immutable concepts through photographic practice. The following work, In lieu of flowers, is an emotional and particularly conceptual way to address violence against Trans people in two social, cultural, and economic contexts. We were able to discuss some of them with Caleb in an interview.

Caleb Cole is a Midwest-born, Boston-based artist whose work addresses the opportunities and difficulties of queer belonging, as well as aims to be a link in the creation of that tradition, no matter how fragile or ephemeral or impossible its connections. They were an inaugural resident at Surf Point Residency and have received an Artadia Boston Finalist Award, Hearst 8×10 Biennial Award, 3 Magenta Flash Forward Foundation Fellowships, and 2 Photolucida Critical Mass Finalist Awards, among other distinctions. Caleb exhibits regularly at a variety of national venues and has held solo shows in Boston, New York, Chicago, and St. Louis, among others. Their work is in the permanent collections of the Museum of Fine Arts Boston, Newport Art Museum, the Davis Art Museum, Brown University Art Museum, and Leslie Lohman Museum of Art. Cole teaches at Boston College and Clark University and is represented by Gallery Kayafas, Boston.

Follow Caleb Cole on Instagram: @calebxcole

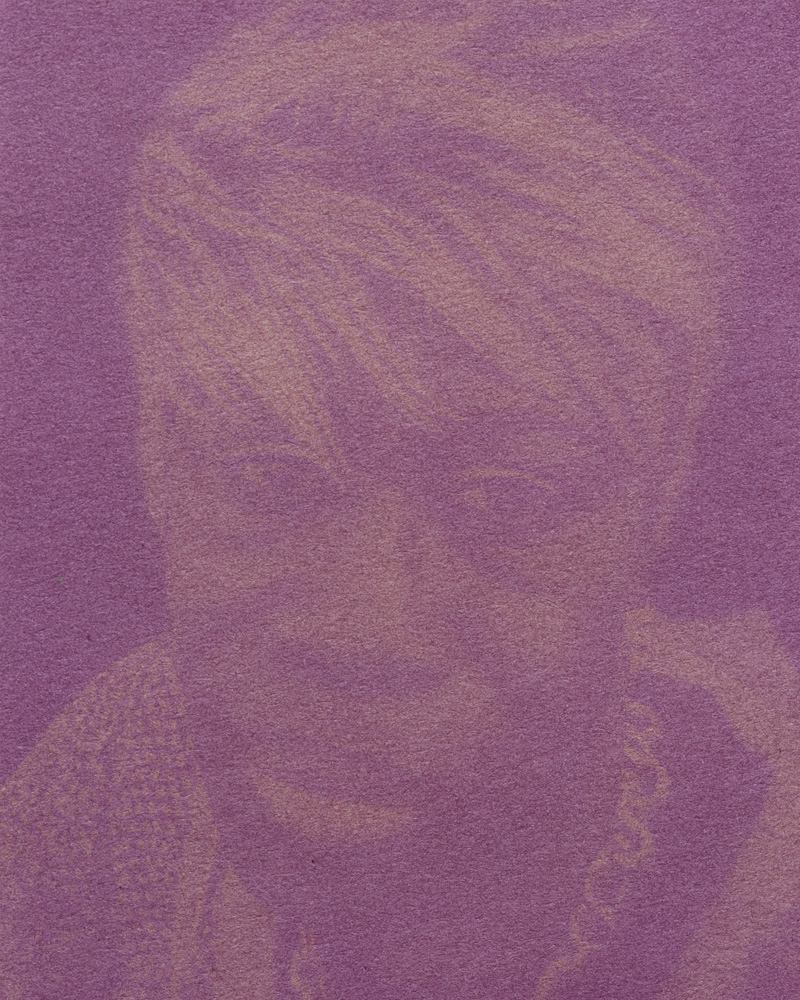

©Caleb Cole, Ashley Moore, 2020, from In Lieu of Flowers, All images 4 x 5 inches, Anthotypes from Rose Petals

In Lieu of Flowers

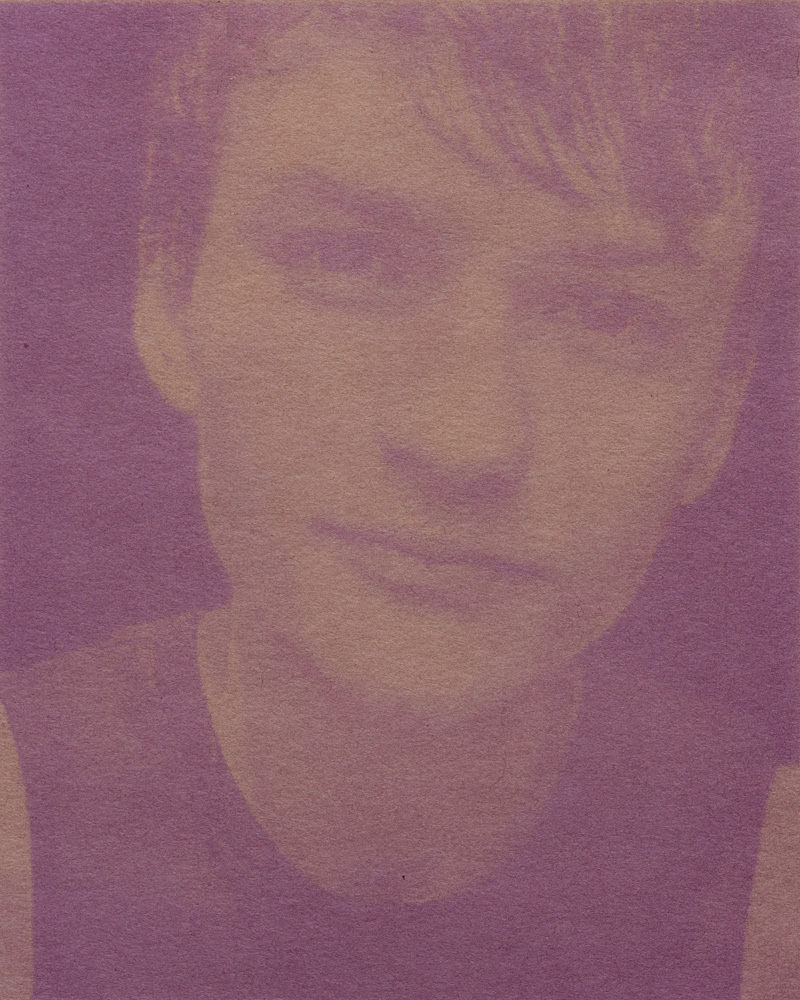

In Lieu of Flowers is an ongoing series of memorial portraits of the transpeople murdered in the United States and Puerto Rico due to transphobia, state violence, and institutional neglect. Part mourning ritual and part photograph, I use the roses from my garden and portraits primarily made by the subjects themselves to create a series of anthotypes, images created using photosensitive material from plants and the sun that cannot be fixed, therefore will eventually fade. This process is an act of devotion and extended witnessing over the course of the days- to weeks-long exposures. When I move the prints from window to window each day to keep them in direct sunlight, I spend time looking into each person’s eyes, connecting with their joy and grieving for their absence. The sun, the source of life, cannot revive them, yet the sunlight that creates each anthotype is the same light that once illuminated each original selfie, connecting us to one another. The resulting work is an examination of community, loss, time, and the impossible effort to extend both the life of my roses and the memory of these stolen lives.

©Caleb Cole, CoCo Chanel Wortham, 2021, from In Lieu of Flowers, All images 4 x 5 inches, Anthotypes from Rose Petals

When googling for the definition of proof, one of the first suggested examples of the word is “you will be asked to give proof of your identity”. Interestingly enough, this emotionally charged work of yours, “in lieu of flowers”, functions both as proof of identity but also as proof of your grief, even if eventually fades away. I am interested in this relationship between identity and a sort of transitional time, could you elaborate on that?

Identity is relational and identity is all about context. We are different with our families and with our friends and at work. We are different across the span of our lives. We are products of our location, place in time, and circumstances. I’m most interested in thinking about who we are to one another and what it means to belong, particularly as it relates to queerness. What does it mean to desire queer community when the very notion of queerness is so elusive and mutable? Is there a queer community, and if so, what responsibilities come along with that belonging? These are things I’m thinking about as I make these anthotypes. Who are we to one another, and if we really take on a belief in a connection to others will anything change?

©Caleb Cole, Dominique “Rem’mie” Fells, from In Lieu of Flowers, All images 4 x 5 inches, Anthotypes from Rose Petals

I very much like the idea of the sunlight that illuminates and connects every human being throughout history. And it is really interesting how you conceive, or rather, assume the impossibility of extending the memory of the murdered trans people. Doesn’t this assumption in a way contradicts the notion of “proof” as something which we could idealize as more perennial?

The idea of a sunlight that connects across space and time, via photography, is actually borrowed from Barthes (who I think was quoting Sontag). Photography for me is so often about this gesture of connection. Nothing is forever. Memory isn’t forever. That’s what’s so beautiful about photography as an expression of our desire to hold on to that which cannot be kept. We want to remember, to keep memories and people alive through our photographs, but it doesn’t work that way. A photograph is not a memory and it is not a person. That doesn’t mean photography is meaningless or we should stop trying, though. I believe the act of trying can be an expression of love, can actually generate kinship.

©Caleb Cole, Draya McCarty, 2020, from In Lieu of Flowers, All images 4 x 5 inches, Anthotypes from Rose Petals

This moving of the prints through the windows in a constant search for sunlight. Were there cloudy days?

Of course. The idea that no matter what they would need tending to is a part of the process. They become a kind of duty, a ritual, something to negotiate, like memories.

©Caleb Cole, Helle Jae O’Regan, 2020, from In Lieu of Flowers, All images 4 x 5 inches, Anthotypes from Rose Petals

©Caleb Cole, Isabella Mia Lofton, 2020, from In Lieu of Flowers, All images 4 x 5 inches, Anthotypes from Rose Petals

I was very moved by this work as an homage. I often think of proof as something quite rational and objective, but we usually also use it as proof of love for someone or something. Do you see any sort of tension, here?

I don’t think of proof as an unchanging fact, but rather something we offer in the process of telling stories and expressing feeling. Rings don’t prove our love to our partners, but we wear them as symbols and as reminders. Photographs can imply time and care spent, and can mark something or someone as valuable. No matter how disposable some may find us (see the Texas governor’s order to investigate transgender health care for minors as child abuse), I believe trans people are valuable and worthy of protection. I really love queer and trans people and think this love is one of the things that connects us to each other.

©Caleb Cole, Nina Pop, 2020, from In Lieu of Flowers, All images 4 x 5 inches, Anthotypes from Rose Petals

©Caleb Cole, Poe Black, 2020, from In Lieu of Flowers, All images 4 x 5 inches, Anthotypes from Rose Petals

©Caleb Cole, Riah Milton, 2020, from In Lieu of Flowers, All images 4 x 5 inches, Anthotypes from Rose Petals

©Caleb Cole, Serena Angelique Velázquez Ramos, 2020, from In Lieu of Flowers, All images 4 x 5 inches, Anthotypes from Rose Petals

Your work shares this simultaneous feeling of delicacy and strength. What is coming next?

Besides continuing this series and a few others, I’m beginning a new project working with some of the books and scraps photographer/collage artist John O’Reilly left behind after his death last year. I think a lot about connection and lineage outside of traditional family structures, and the importance of connecting to the queer artists who came before us is definitely part of that. John’s work has been incredibly important to me for a long time and I want to have a conversation with him through his materials in a way that might cross time, cross death.

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

Jonathan Silbert: InsightsFebruary 19th, 2026

-

Olga Fried: Intangible EncountersFebruary 18th, 2026

-

Anne McDonald: Self-PortraitsFebruary 17th, 2026

-

Review Santa Fe: Elizabeth Z. Pineda: Sin Nombre en Esta Tierra SagradaFebruary 6th, 2026

-

Carolina Baldomá: An Elemental PracticeJanuary 5th, 2026