Photographers on Photographers: Sara J. Winston in Conversation with Linda Moses

I first met Linda Moses a few years back when we were both members of the photography collective Collective Envelope.

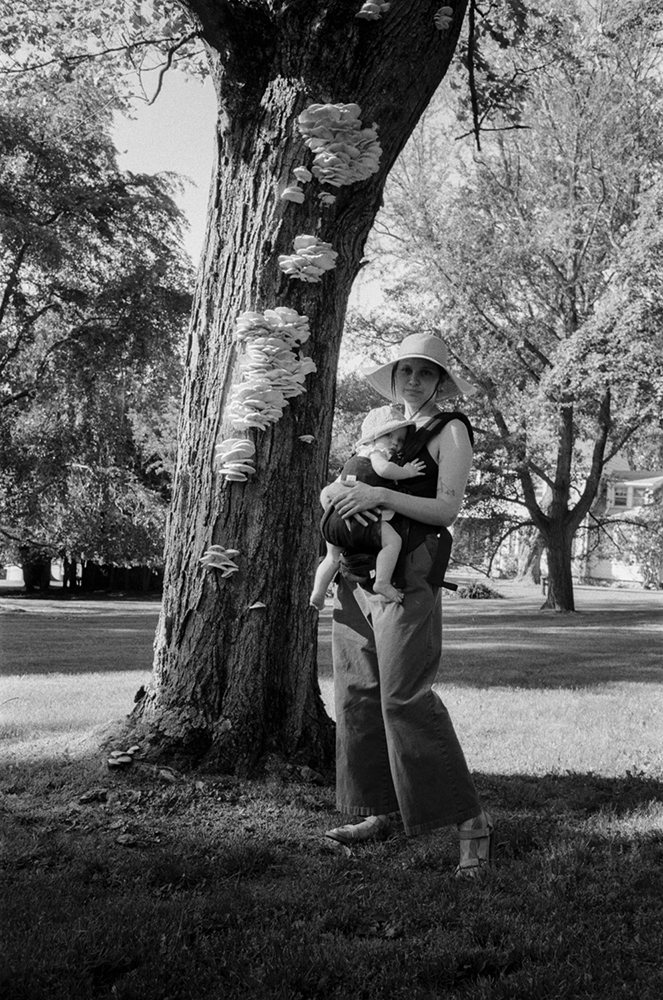

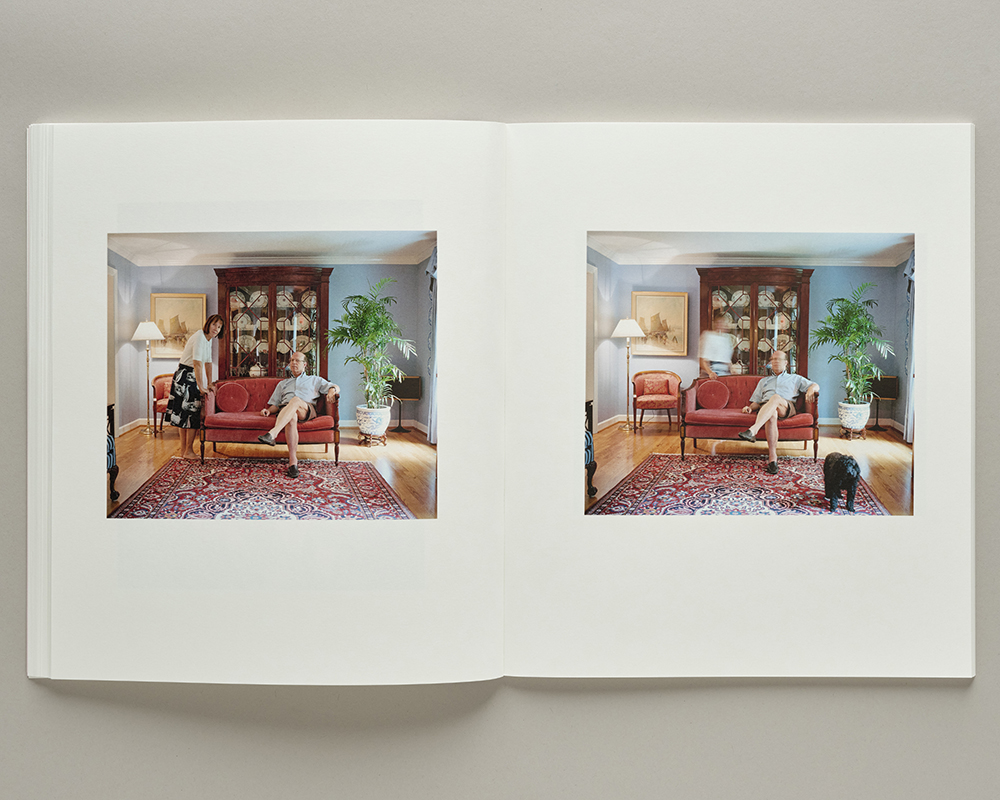

Linda’s color photographs, particularly those of her parents and her childhood home made with a Mamiya 7ii, immediately struck a chord with me. I wanted, and still wish to make portraits more akin to those made by Linda in her series To Know You (Now and Then). She wields her camera with an eloquence, curiosity, and mastery that allows a truly vibrant energy to flow through her photographs. So when Linda mentioned in one of the Collective’s meetings that she was beginning discussions with Smog Press about making To Know You (Now and Then) into a book, I couldn’t wait to see it come to life.

In the spring of 2023 the book was released. It is delicious. Before you read on, consider picking up a copy here, as there are only a few copies that remain available from the publisher.

Linda Moses (b. 1994) is an artist and educator based in Albany, New York. She received her BA in Art History from William & Mary and MFA in Art Photography from Syracuse University. Working in photography, text, and video, she researches the intersecting notions of selfhood, family, truth, and memory. Her work has most recently been shown at Study Hall Gallery in Utica, NY, the Syracuse University Art Museum in Syracuse, NY, Governor’s Island, and Villa Heike in Berlin. Her first monograph, “To Know You (Now and Then),” was published by Smog Press in 2023, and she was recently awarded a Light Work Grant in Photography. She currently teaches Photography and Media Arts at Syracuse University and Pratt Munson in Utica, NY.

Follow Linda on instagram at @_lindamoses

Sara J. Winston: I’m curious to know what interests and/or events in your life led you to become an artist; particularly how those interests and events continue to influence the way you think of the work you make today.

Linda Moses: Growing up, I knew I wanted to be an artist, but I never knew what type of artist I would be. It’s not that I was drawn to any specific artform like photography or painting or something; it’s more that I felt this pull to look at the world with curiosity and to make sense of what I was feeling.

I’ve always been fascinated by what we choose to remember and how. When I turned ten, I remember feeling particularly awestruck by the fact that I was this new age. To commemorate the feeling, I found the nearest blank surface– I think it was a box– and using a sharpie, I wrote something like: “Today I am ten years old. I am ten years old today and I never want to forget this moment.” I don’t know where that box is but I’d love to find it.

I took my first photo class in college– it was an introduction to large format photography. I immediately fell in love with film; it seemed like the perfect medium for addressing questions of memory and time. The act of making a picture and having to wait before I could see it felt like magic, and it still does. Photography became the way I could articulate something that I would have to come back to later– to reckon with.

How about you? I’m equally curious to hear about how events in your life have found their way into your work.

SJW: I was very fortunate to have a parent who was always very vocal about the importance of education for education’s sake, and that one finds their way to a career as they pursue their education and passion. My parents were both pretty hands off, and as a teen I was given a lot of unmonitored space to explore my interests and figure things out for myself. The only interest that did not bore me over time was photography. So I worked like hell to get myself some scholarship money to pursue that path.

Chronic illness and parenthood, two events in my life that I couldn’t anticipate and did not plan for, have been utterly perplexing life experiences. It has been a natural impulse for me to photograph through the moments of these multifaceted experiences–the good, the bad, the weird– in order to see both illness and parenting more clearly for myself. Then in the editing of the work I feel empowered to emphasize certain emotions and moments.

When did you begin to photograph at home? To look at your parent’s as subjects, or perhaps rather than subjects as your collaborators, and to see the house of your childhood as a setting for your work?

LM: I relate to the way you describe photographing as a natural impulse for dealing with all sorts of emotions; for me, it has become the primary tool I use – along with writing– to process the good moments in life as well as the unpredictable changes.

Though I had photographed my parents occasionally before, I began photographing them more seriously in 2019. In late 2018, my uncle was diagnosed with terminal cancer and died a few months later. It was a huge shock for the family, and the first time that I faced the death of a loved one. At the time of his diagnosis, my uncle was 70 years old. Because my parents were in their late sixties, I noticed their interactions start to change as they processed the reality of my uncle’s death and confronted the unpredictability of illness. I started photographing because it was the only thing that made sense – for the first time, I saw my parents as people who weren’t invincible to death, and I wanted to capture this newfound reality in images. Time felt palpably different.

Over time, the house has become a character in its own right. I always had this idea that the house was unchanging, that it was the most consistent thing in our lives. But since starting this project (To Know You (Now and Then), I’ve noticed aspects of the house that I never really paid attention to as a kid. I think walking around with a camera necessarily does that – you notice patterns of light that fall at a certain angle or the way colors change depending on the time of day. It’s exciting to realize that no matter how familiar something is, it will always appear slightly different. It’s also been interesting to understand the house in relation to my parents’ personalities rather than separate from them. I learn who my parents are in terms of objects in the house, and imbue objects with a sense of their character.

Can you describe what you felt when you were first diagnosed with Multiple Sclerosis? When did you decide to start photographing your experience, and how has that process changed over the years?

SJW: This is a tough question to answer, how I felt when I was first diagnosed, I mean. I still get choked up thinking about it. I think the pithiest answer is that the day of my diagnosis was the day my youth ended. It was a big kick.

I began photographing myself right away. The first portrait of my infusions was made on July 26, 2015. For a long time after that I photographed just my hand, the site of infusion, every 28 days, without ever misssing one. But it wasn’t until 2019, when I became a parent, that I began to make more formal photographs of myself receiving infusion therapy.

It’s been nearly nine years. For the first five of those years I almost exclusively used my mobile phone and its camera to look at the site of the IV line. And then in 2019 when I began using a tripod and remote, I never went back to the camera in my pocket. Now I’m full speed working toward a book of the infusion work, which I have been calling Our body is a clock.

Please tell me about making (To Know You (Now and Then), the beautiful book you produced with Smog Press this year. I’m curious about the impetus for the writing, and the voice of the writing, as well as the sequence and design choices. Does the book mark an ending of the collaboration with your parents, with the house?

LM: When Smog reached out to me about making a book in 2021, I wasn’t sure I was ready. I had this idea that a book was the end of a project, and this project is the opposite of an ending to me. But we talked about what the book could be, and I started reframing the project’s relation to the book form. I started to see it as a chapter in a longer story, and that helped free me from this feeling of great pressure.

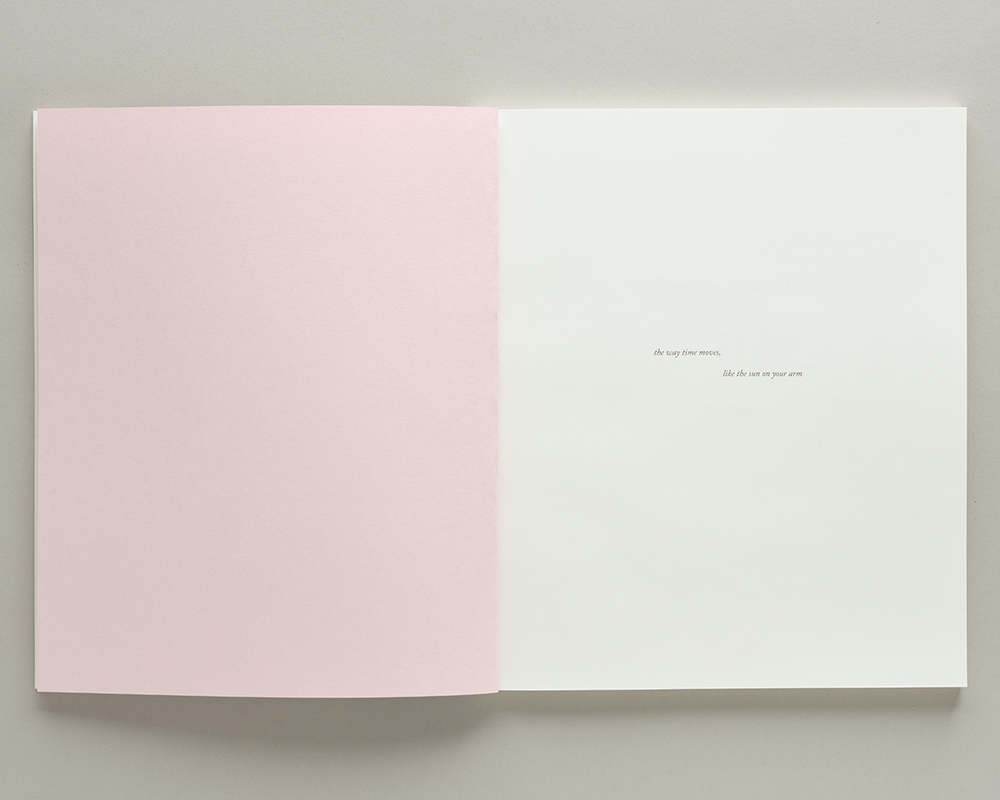

I had so many ideas at first about how I could arrange images on the page, but I also wanted the book to hold a kind of simplicity; I didn’t want the design to speak louder than the life inside the images, if that makes sense. We went through multiple sequences, with gaps of time in between each one and with little changes along the way. I don’t feel like the book would have been possible without taking time and space away from each sequence. The process was intuitive, and I started to feel like I was developing a world that made sense– one that aligned with the dreamlike state I found myself in whenever I returned to my childhood home.

There wasn’t always writing in the book. I always had this feeling that text would be nice, but it took some time to figure out how I wanted the words to function. To be honest, phrases would kind of pop up in my mind randomly when I was thinking about the work, sometimes after zoom calls with Taylor and Adam when we talked about certain images or changed the sequence. The text evolved from realizations I was having about the work or memories I would connect to in real time. Also, I’ve always been interested in the way text can function as an image in its own right. I knew that if text would live in the book, it shouldn’t be a caption for the pictures but instead expand what could be visible in them.

To your question about whether the book is an ending, I don’t think so. I guess I see it as one iteration of an ongoing process. All I know now is that the project is evolving in the same way time is moving and my parents and I are changing.

How has it been for you, developing Our Body is a Clock into the book form? I’m curious if this process feels different from the making of your previous books, like A Lick and a Promise or Homesick? What is your process like?

SJW: For all three I envisioned the work to be in book form. I love reading books and making them. I hesitantly admit, I am obsessed with books.

The process of making Our body is a clock does feel different. This book feels much more ambitious than any other I’ve pursued. I feel more vulnerable in the work, for one, because I am in the photographs in a way that I haven’t been previously. I’m working on a long piece of writing to go in the book, as well as an interview with another artist. While I’ve written before it has been very short, specifically for A Lick and a Promise. So a lot feels new this time which is thrilling and a little scary. I’m not rushing the process. I’m trying my best to give each aspect the time that it needs, the time that I need.

I’ve heard murmurs that To Know You (Now and Then) might have sold out recently at the Printed Matter LA Art Book Fair. How does that feel for you? Are you thinking about the next chapter, the next book? What’s on the horizon for you as an artist?

LM: I’m so excited to see the book and to read your writing. I think that often the best writing comes from a scary place. Or at least, being willing to traverse difficult emotions and articulate that experience in words. I wonder if you have any books you turn to for inspiration, photo or otherwise? Or more generally, what sorts of media have moved you lately?

And yes, I believe we are down to the very last copies of the book! It feels surreal and wonderful to know that other people have this book in their homes– that a world that was personal for so long has found its way into other people’s lives and that they resonate.

I’m currently working on a video piece that takes some of my parents’ descriptions of their childhood homes as voice over and overlays footage taken from my surroundings here in upstate NY– the work is very new, and so far I’ve only recorded some audio. Video is something I’m trying to incorporate more of into my practice; I love the way still and moving images can give meaning to each other.

Beyond that, there’s a body of work I’ve been quietly developing that I don’t really have the words for yet – a combination of self portraits and still lives. I’m just letting the images guide me toward meaning. It’s exciting to not really know what it’s going to amount to.

SJW: I love that your collaboration with your folks is ongoing and not anchored to the house of your childhood. And I’ve loved the self portraits you’ve shared with me in the past and am thrilled to hear that you’re making more. I am eager to see them when you’re ready to share. I’m curious if you have thought about working with your partner in any capacity?

Here are a the things that have been in my rotation this summer, in no particular order:

Swimmers by Larry Sultan (MACK, 2023)

Natural History by Carlos Fonseca (Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2020)

A Practical Theory of Photography: Rashod Taylor and Dan Estabrook in Conversation (Dan Estabrook, 2022)

Health edited by Bárbara Rodríguez Muñoz (Whitechapel Gallery & MIT Press, 2020)

The Hudson Valley by Stephen Shore (Blindspot, 2011)

Japanese Death Poems edited by Yoel Hoffmann (Tuttle Publishing, 1986)

The Uses of Enchantment: The Meaning and Importance of Fairy Tales by Bruno Bettelheim (Vintage Books, 1979)

funeral playlist by Ryuichi Sakamoto

What were you looking at as you worked to shape To Know You (Now and Then) as a book? And similar to your question to me, what media are you ingesting these days?

LM: To your first question, I’ve taken some images of my partner and have been considering incorporating them into the newer project. This year has been big for us, with marriage and moving, and it’s brought a range of emotions with it. There are several ideas that I want to turn into images, even if just to process what I’m feeling.

I can’t talk about inspiration without mentioning Chantal Akerman. I’ve been really influenced by the pacing of her films and her attention to detail, especially Jeanne Dielman, 23 quai du Commerce, 1080 Bruxelles (1975) and News from Home (1976). I feel like I always have that sensibility running through the back of my mind. I would be remiss not to mention Tarkovsky’s Mirror (1975). I love that film. I’ve also often returned to Moyra Davey’s writing in Index Cards, Camera Lucida by Barthes, and The Art of Memoir by Mary Karr. Some photo projects that I think of often: Doug Dubois’ All the Days and Nights, Sian Davey’s Martha, and Deanna Dikeman’s Leaving and Waving.

These days, I’ve been making my way through Natalia Ginzburg’s writing, starting with Family Lexicon. I love the way she taps into her family’s mode of communicating and the inherent mystery of language. She’s so brilliant.

For a good mood: Djavan’s album A Voz, o Violão

For big feelings: Ingmar Bergman’s film Autumn Sonata

Speaking of media that inspires me, I can’t wait to receive your newest publication, Shades, which you made in collaboration with Aaron Canipe and Nat Ward through Push Pull Editions. It looks so beautiful! I have followed your photographic conversation with Aaron on “A New Nothing,” so I can’t wait to see its book form.

SJW: Thank you, Linda! Shades is in production now, I am eager for it too. Thanks for chatting, and hopefully 2023 will be the year we meet in person for the first time!

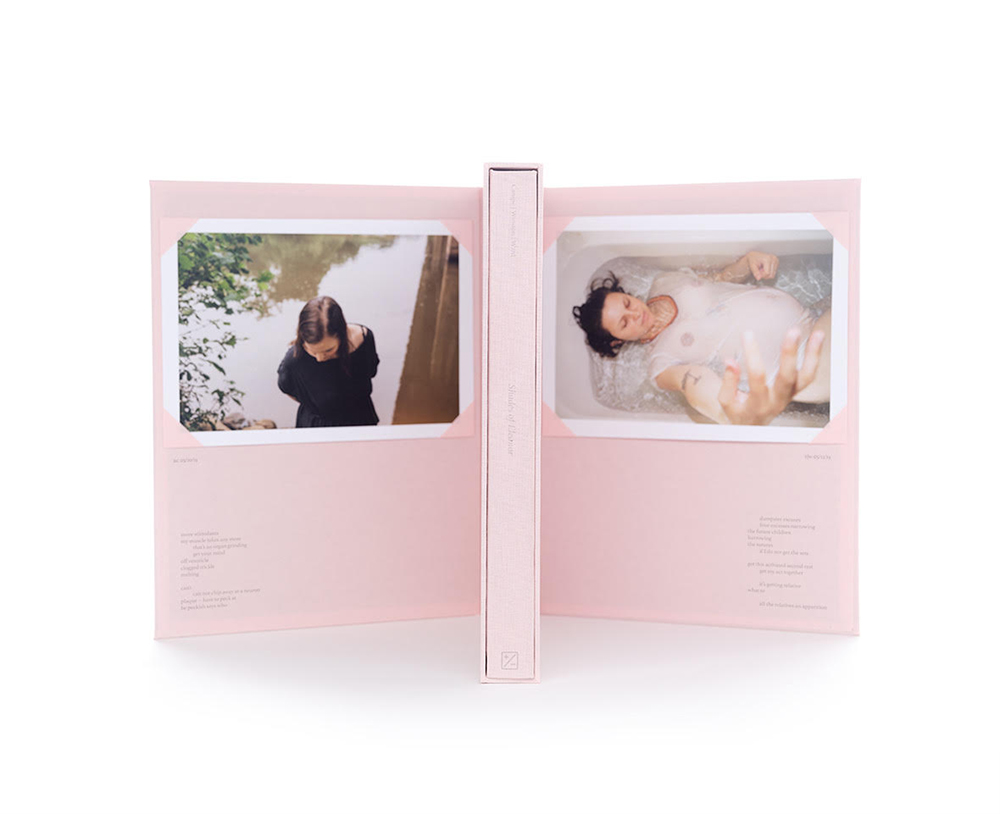

© Sara J. Winston, book spread from Shades (Collector’s Edition), published by Push Pull Editions, 2023

Sara J. Winston is an artist based in the Hudson Valley region of New York, USA. She works with photographs, text, and the book form to describe and respond to chronic illness and its ongoing impact on her body, mind, family, and memory. Sara is the author of several photobooks, among them Shades (collaboration with Aaron Canipe & Nat Ward; Push Pull Editions, 2023), A Lick and a Promise (Candor Arts, 2017) and Homesick (Zatara Press, 2015). Sara is the Photography Program Coordinator at Bard College; on the faculty of the Penumbra Foundation Long Term Photobook Program; Adjunct Professor at Syracuse University; a contributor to Lenscratch; and a member of Storm King Art Center‘s Accessibility Advisory Group. On June 29, 2023, her long-term project about multiple sclerosis care, Our body is a clock, was adapted and published as an op-ed in the New York Times, titled ‘My body is a clock’: The Private Life of Chronic Care.

Follow Sara on Instagram at @sarajwinston

Smog Press is a Los Angeles-based independent art book publisher. Founded in 2021 by Adam Ianniello & Taylor Galloway, Smog Press specializes in small edition photography and design books.

Intagram: @smogpress

Push Pull Editions is an independent book press located in Corvallis, Oregon that focuses on publishing photographic books with a documentary focus in small edition runs of 100-250 copies. All design and production is completed by Evan Baden.

Instagram: @pushpulleditions

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

Earth Month Photographers on Photographers: Jason Lindsey in Conversation with Areca RoeApril 21st, 2024

-

Earth Month Photographers on Photographers: J Wren Supak in Conversation with Ryan ParkerApril 20th, 2024

-

Earth Month Photographers on Photographers: Josh Hobson in Conversation with Kes EfstathiouApril 19th, 2024

-

Earth Month Photographers on Photographers: Leonor Jurado in Conversation with Jessica HaysApril 18th, 2024

-

Earth Month Photographers on Photographers: Sarah Knobel in Conversation with Jamie HouseApril 17th, 2024